Early years

The great Russian writer Fedor Dostoyevsky said: “The secret of a human being is not his life, but rather the purpose of his life.” Sattar Bahlulzade was born in the village of Amirjan, near Baku, in 1909. He lived most of his life in the village –

At the time, he would draw pictures of old houses and mosques in his home village, and the contrasting countryside of the Absheron Peninsula. In summer, he painted sketches and landscapes in the village which often featured mulberry, almond, apricot, fig and pomegranate trees surrounding houses. Prominent Azerbaijani painter Azim Azimzade was aware of Sattar’s work and offered him a job at the Communist newspaper, where he was the chief illustrator at the time. Sattar’s Famous main work there was to draw illustrations and cartoons for critical articles published in the newspaper.

Drawing cartoons was not for Sattar, however. He could not put his heart and soul into what he had to draw. Nevertheless, the young Sattar felt the enormous influence of his teacher, Azim Azimzade, on his cartoon drawing and started to think seriously about his own way of painting. Sattar’s greatest dream was to continue his education. Finally in 1933, Sattar Bahlulzade was sent to the Surikov State Painting Institute in Moscow at Azim Azimzade’s vehement insistence. Sattar entered the institute’s graphics faculty where he studied in the workshops of Vladimir Favorskiy and Lev Bruni. For the rest of his life, Sattar Bahlulzade had fond memories of Favorskiy, who inspired a love of beauty in his student. Sattar worked at Favorskiy’s studio until his third year at the institute, and then moved to Prof Grigoriy Shegal’s studio. Shegal, who was an excellent teacher and colourist, was an enthusiastic instructor of the young Azerbaijani. From the very first lesson and sketch, the great teacher realized that Sattar Bahlulzade had a natural talent for landscape painting, and that he had the ability to feel colours. He advised Sattar to choose landscape painting, as that was where his greatest talent lay.

Seeking his artistic direction

An artist seeks and experiments all his life in pursuit of his own style. When Sattar Bahlulzade finished his studies in Moscow in 1939 and returned to Baku as a professional painter, he was still looking for himself and his own style. At the first exhibition held in the republic in 1940, Sattar Bahlulzade exhibited a painting Defence

However, these were not enough to reveal Sattar Bahlulzade’s inner potential. French painter Pierre Auguste Renoir wrote: “Every artist who has devoted his entire life to art should listen to the voice of his heart rather than to the dictates of his century. He should always live with the feeling of change and innovation.” Sattar Bahlulzade was the kind of artist who always looked for change and innovation. In the early years of his career, the artist could have earned his living by drawing cartoons and attractive paintings about history and heroism. He did achieve some success with a series of paintings on these topics in the 1930s and 1940s, but he gradually turned away from this artistic direction.

Sattar tried out genres such as industrial and nature painting. His first industrial landscape, First Oil in Buzovna, was drawn in 1947. His nature landscapes Dawn, The Road and Buzovna were instantly popular, but First Oil in Buzovna drew serious criticism. The main shortcoming of First Oil in Buzovna was that the natural scenery was painted skilfully, but the oil drills were weak. This was not in keeping with the ideology of the time. Upset by this failure, Sattar Bahlulzade left Baku for a long time. He spent time in various parts of Absheron, painting the beautiful scenery of this region. Unique paintings such as Amirjan, Night Over the Caspian, The Beauty of the Caspian, Eternal Fire, Surakhani Atashgahi (Fire-Worshippers’ Temple) and The Crown of Absheron were the result.

Having completed a series of landscapes dedicated to the Absheron Peninsula, which he called Landscape of Dreams, Sattar Bahlulzade decided to dedicate himself to nature forever. He went to Quba District in the north of Azerbaijan where he soon produced the series Quba Scenes. The landscapes from Sattar Bahlulzade’s series – Qudyalchay Valley, The Road to Qizilbanovsha, In the Gardens, The Banks of Qudyalchay, Green Carpet, Autumn and On the Slopes of Shahdag – were displayed first at exhibitions in 1953-54. These paintings were valued highly by both experts and the art-loving public. They also brought him great fame. From that moment on, Sattar Bahlulzade was known as a great master of landscapes with subtle feeling.

This success encouraged Sattar to embark on even more challenging work. He found that he had a natural talent for landscape painting and expanded his research in this direction. Initially, Sattar could be found in only two locations – on the Absheron Peninsula, in villages far away from Baku, and in Quba District. But he later visited Lankaran, Karabakh, Mugan, Mil, Nakhchivan and other regions of the country. In those regions, he drew beautiful, unique sketches for his future works. These sketches led to monumental landscapes that are admired greatly by art lovers, such as In Lankaran, Sea Shore, Native Horizons, Road to the Mountains, Foggy Mountains, Upper Dashalti, Jidir Duzu (a racetrack in the town of Shusha), Shusha Suburbs, Tale of Azerbaijan and Shakhnabad Waterfall.

Sattar Bahlulzade developed his work on both natural and industrial landscapes simultaneously. This was not without a reason. The painter could feel better than anyone the poetry of oil drills, which had been a feature of his childhood. Despite his first unsuccessful work in the genre – First Oil in Buzovna – Sattar Bahlulzade expanded his research. In 1954 he visited the Oil Rocks offshore drilling complex, which was dubbed Island of Miracles at the time. He immediately became fascinated by the Island of Miracles. Sattar drew dozens of sketches there. He returned to Baku full of impressions and ideas about future oil industry landscapes. This led to the large canvases Night over the Caspian, The Beauty of the Caspian, View of Oil Rocks, Pier, and Heroic Epic.

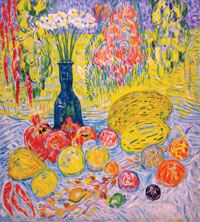

Everyone was fascinated by these paintings. The works on the same theme – Eternal Fire, Oil Drills in the Sea, Old Fire and Land of Fire – emerged later. The key to the success of these industrial landscapes is their harmonious combination of nature and industry. In the turbulent natural landscapes everything is in motion. The dullness of the industrial views fades away against the backdrop of this action, and the beauty of nature emerges. A celebration of the real and romantic worlds starts in close harmony.

Lover of nature

The beauty of the Azerbaijani landscape is the subject of the landscapes Spring Morning, Autumn Time, First Snow, Suvar, Khinaliq Plateau, Spring Night, Spring in Mugan, Nakhchivan Landscape, Dadagunash, The Tears of Kapaz, Awakening, Gulustan, In Azerbaijani Gardens, Bazarduzu, Shahdag, The Mountains of Shahnabad, The Beauty of Mugan, Land of Legend, Mountain Flower, Goychay and Caspian Shore. These are romantic, lyrical works. The landscapes provide snapshots of unusual moments on the Azerbaijani land. But it was no easy job for Sattar.

It took him much time and energy to capture these moments. Sattar acknowledged this. He said: “Many people think that I can take a clean canvas and a paintbox and easily paint various moments in nature whenever I wish. They are wrong. This is not the case at all. I have always had a habit: most of the time, I first draw sketches for my pictures. Sometimes I do not draw sketches, but keep them in my memory. For instance, the landscape The Tears of Kapaz is drawn from memory. I did not draw any sketch for it. I had no opportunity to do that at the time anyway.

“I remember my visit to Goygol together with Tahir Salahov and Togrul Narimanbayov. I woke up early in the morning and looked around. The sun was just rising. In the dawn, Kapaz [mountain] looked unusual to me. I cried out instinctively, waking Togrul and Tahir. They joined me where I was standing and we looked at the unusual scene. None of us said a word or did anything. But I remembered that sight with all its brightness and mood. I copied that scene onto the canvas upon my return to Baku and called it The Tears of Kapaz. Togrul and Tahir were astonished when they saw the picture. “I want to take this opportunity to say one more thing. We have seen many pictures of Goygol so far. Of course, you can draw pictures of a thing or place many times. This is not very dangerous, because every painter has his own approach and attitude to an object. What is most important is that a painter has to have his own creative view, his own fantasy and creative thinking so that he does not look like others or repeat what other people have already done.”

Classical miniatures and impressionism

Sattar Bahlulzade was the kind of artist who always tried to convey the essence and nature of the landscape he painted. This was the reason his creative life was full of unexpected moments, bright colours, mysteries, energy, emotion and music. Some people say that his works were influenced by the classical miniature art of Tabriz, others that they were influenced by Impressionism. From his youth, Sattar Bahlulzade had been familiar with the 16th-century Tabriz school of miniatures, and its great founders,

The minor-major harmony of the Tabriz miniature school and the desire of Impressionism to come out of the dark helped Sattar in his development. It would be wrong though to connect Sattar Bahlulzade’s work only with those schools and trends, and to say that the mystery, light, warmth, music, philosophy and aesthetic views in his paintings derived solely from miniatures and Impressionism. The roots of Sattar’s remarkable work can be traced to his own character. Despite his untimely death (he died in Moscow on 14 October 1974), Sattar Bahlulzade emerged victorious in his art. He brought novelty, lots of light, energy, music, harmony of colour and perpetual motion to Azerbaijani painting.

Music and colour

Musicality is the lifeblood of Sattar Bahlulzade’s work. His paintings are a huge musical note written in bright colours. Music and energy come out of the colours. The colours sing, and radiate light and energy. Where did these bright colours, this minor and major harmony come from? Maybe Sattar was a musician greater than his time, a composer, or poet who realized better than anyone else the colours and musicality of nature? Yes, he was a great composer, a painter and poet greater than his time, who felt the unseen colours and musicality in nature better than anyone. This is how he will always be remembered. It is also worth talking about Sattar’s colours, which prompted much debate at the the time. Sattar used unusual and unique colours, which he seems to have invented himself. But the artist himself did not agree. He would always say: “I do not look for a colour, nor do I create one. I try to paint things as I see them. But remember that everybody cannot see things in the same way. Everyone has their own perspective, their own view, understanding and memory. Everyone sees and perceives colours – yellow, blue, pink and orange – in their own way. Therefore, these colours appear differently on canvas.”

A unique individual

It was Sattar. I asked how he was. He was very upset. I decided to tease him to cheer him up. “‘What’s up, you, grandson of Fuzuli [a Medieval Azerbaijani poet]? Why are you so upset?’ I asked. He did not reply. It took a while before he finally pleaded with me like a naive child."

"'Togrul, I don’t feel well. I think my heart will stop beating if I don’t get out of the city tonight,’ he said.

“I thought he was drunk, so I joked again: ‘Don’t worry. You’ll be OK by the morning,’ I said.

“‘I won’t, Togrul,’ he replied. ‘Let’s meet near Baki Soveti,’ he said.

“‘Sattar, why don’t you come to the studio? Come along, we’ll have a chat and remember great Fuzuli,’ I said.

“‘If you really care about me, you’ll come,’ he said.

“I knew that he would never forgive me if I didn’t go. So, I went to meet him although I was very tired. He was waiting for me with a taxi. We shook hands and I asked him what had happened. Getting into the car, he only said: ‘I miss Qizbanovsha [a mountain], Togrul. We’ll go there now.’

“‘In the dead of night? What if we slept tonight and went there early in the morning?’ I asked.

“‘No, Togrul,’ he replied. ‘We’ll go now and get there early in the morning.’

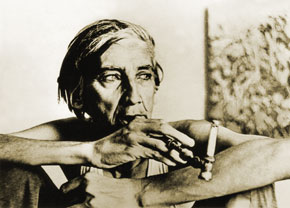

“We left to Baku and arrived at Qizbanovsha when the sun was about to rise from behind Shahdag. Getting out of the car, he jumped into the moist grass and hugged it. “In fact, I did know that Sattar was a great lover of nature. We had spent a lot of time together in Shahdag, Goygol, Kapaz, Qarayazi, Shusha, Jidir Duzu, Batabat, Qizilagaj, Mugan and Mil. But to be honest, I had never seen him so crazy about nature before. I finally saw him and was astonished, which led to my monumental work, Sattar Bahlulzade. In this picture, I drew Sattar the way I had seen him and perceived him: he was passionate, furious and annoyed."

“It is true that Sattar was different from others in his art, but he was also unique in terms of his character. At times, he was extremely friendly. But sometimes he was furious and angry. Sometimes you could see him abandoning his very old friends, shutting the doors of his studio and heart to them forever. But sometimes he would present his paintings to people he did not know very well or had never seen before. This is the reason many of his paintings are now owned by different people in every corner of the world."

“But sometimes this friendly and generous man would turn into a capricious child. At moments like that, he shunned everybody and everything – his friends, relatives and studio – and retreated to nature. He sometimes looked more like a Sufi or Shaman than a painter."

“Yes, Sattar Bahlulzade did not look like the people around him, nor did he resemble his own paintings. With his strange appearance, big blue eyes, and long grey hair, Sattar looked like a mysterious, legendary figure that has emerged from the Absheron deserts, tanned by its scorching sun."

“Many people who walked alongside him in the street, or travelled with him in trains or buses, or sat next to him in tea houses did not know that this modest man was Sattar Bahlulzade, whose art they loved passionately and whom they always dreamed of meeting."

“For all his peculiarities and capriciousness, Sattar Bahlulzade was always loved by artists and by ordinary people as a man and as a painter. Everybody loved and respected him and his work. This was why, starting from the 1940s his works were displayed at republican exhibitions (in 1940), and also at Soviet (in 1946) and international (in 1957) exhibitions. His solo exhibitions were organized both in the former Soviet Union and abroad in 1954, 1955, 1964, 1973 and 1977. Due to his great achievements in art, the honorary title of People’s Artist of the Republic was conferred on him in 1963. In 1972, the State Award of the Republic of Azerbaijan was conferred on him. Prominent people in Azerbaijan and around the world are fans of his work, including Anton Refregier (USA), Andre Fougeron (France), Vladimir Nechitaylo (the Russian Federation), Rasul Rza, Mikayil Abdullayev, Togrul Narimanbayov, Bakhtiyar Vahabzade, Omar Eldarov and Anar (in Azerbaijan).”

Azerbaijani People’s Poet Rasul Rza and People’s Artist Mikayil Abdullayev made some accurate comments. Rasul Rza wrote: “These colours and sketches speak to me in their own language. I met these colours and paints in Sattar’s world. A real artist never dies.”

Mikayil Abdullayev wrote: “He was one of the few artists who sacrificed his life for eternal art in order to please the hearts and tastes of people and to prove the truth -‘life means beauty’. There can be no death for a master like Sattar Bahlulzade! He is the son of all ages. His name will remain in the history of Azerbaijani culture.”

Sattar on art

“You can be called a great artist only when you are capable of creating what you want to see and hear.”

“When speaking about artists, for some reason people say they were influenced by great artists that lived before him or were their contemporaries. To be honest, if somebody expressed the same views about me, I would never agree with them, because whoever is called an artist must have their own direction and style above all.”

“Strong feelings and sense! You cannot become a real painter if you do not have these two beautiful gifts.”

“The colours complete one another to create a strong colouring that resembles the moments of gaiety in life.”

“I am not like Gauguin, who used to retreat to the island of Tahiti for inspiration and nature. I do not advise this to anyone either. Because I think that the life of your own people and your motherland are the real sources of inspiration.”

“Looking at the 10,000-year-old paintings on the rocks in Qobustan, I think that there was no religion or complex human relations when art emerged.

It is as old as life itself. Art should always give hope to people.”

“As a painter, I have been greatly influenced by three important areas of art: our old carpets, our miniatures and the great poetry of Fuzuli.”

About the author: Mohbaddin Samad wrote the script for the documentary There Lived One Sattar in this World (1992), and is the author of dozens of academic and popular features and articles.