There are paintings that have a certain aura to them, the kind that compels your attention to linger on them, to remember them. Those paintings almost feel like memories, unexplainably awakening nostalgia for places I’ve never seen and people I’ve never met.

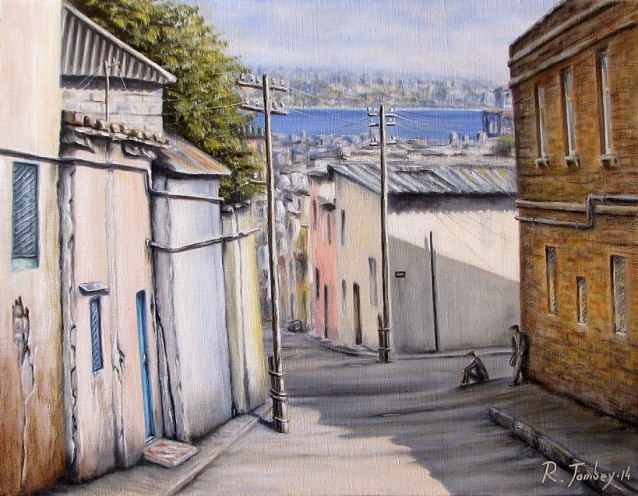

Even though he doesn’t entirely exclude people from his art, he rarely adds them to the scene. All the while the sense of solitude never leaves the canvas, slightly touching each portrayed fragment of life with its cold fingertips.

Even before my introduction to the master himself, I’d learnt to correctly identify his favourite themes. What drew me to this particular artist was the fact that he is not an artist in the first place. Or at least not in the usual sense of the word that implies years of professional training and countless hours with tutors — Mr Rauf Janibekov hasn’t spent a single day in an art classroom.

And not because I couldn’t, but because it was interesting for me to get to know myself and see whether I could become an artist by myself, without anybody’s help. My tutors were books, famous reproductions and practice. I read, practiced, got it wrong, then read more and tried again.

Those paintings almost feel like memories

First steps

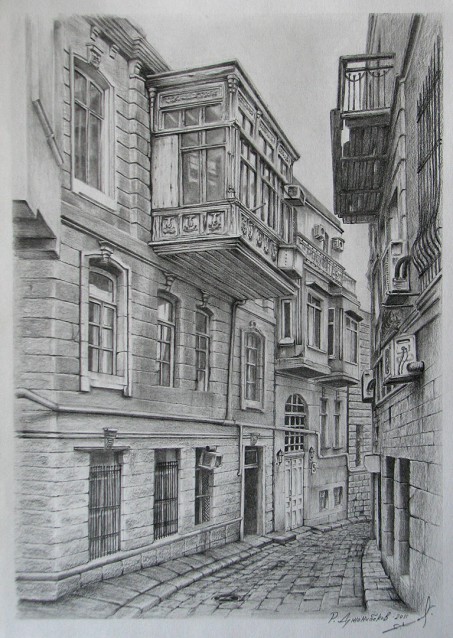

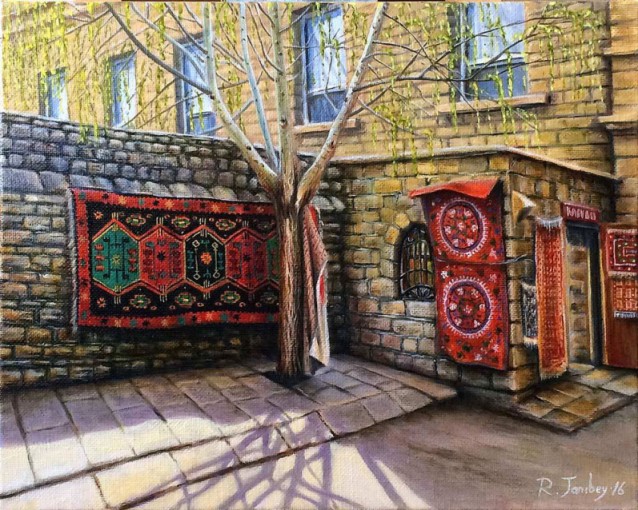

He was born on Nizami Street, not far away from Qosha Qala, but his parents used to live in Icheri Sheher (the Old City), which in part may explain his profound love for it. As a boy, he used to spend hours walking around the city, mesmerized by the incredible architecture of the old buildings, almost “touching” time, totally submerged in the world of Icheri Sheher.

Art in some form or other has existed in his life for as long as he can remember. His favourite childhood pastime was closely examining reproductions of the works of great masters. Mostly those were postcards that we had a lot of in our home. My parents noticed my interest and bought me my very first art supplies: pencils, charcoal, inks and paints. Later, trying his hand in every medium available, from carving on wood to clay modelling, Rauf ultimately found himself drawn to paints most of all. The smell of oil paint was the most desirable for me, he says. He embraced art as part of his life and in their old home, going through the extra back door to the backyard, he found long curvy corridors which he turned into his canvases, covering almost all of them with his landscapes.

His pursuit of artistic aspirations continued until his entry to the Azerbaijan State Medical Institute. As he admitted himself after 30 years of medical practice, this sphere, and surgical practice in particular, does not tolerate any other interests. Once in a while, I’d have episodic creative bursts, but they would happen rarely and be impulsive in character.

I don’t remember my first painting, but I remember trying to oil paint on a piece of thick album paper, which soaked in the oil, leaving stains, so I quickly realized that paper is no good. Canvases were not very easily acquirable in those days, so I started to use plywood, but it also soaked in the oils, making the paint swell and colours fade, losing its depth. And then the answer came by itself – I used regular paint on top of wood, and after it dried I’d paint over it with my oils.

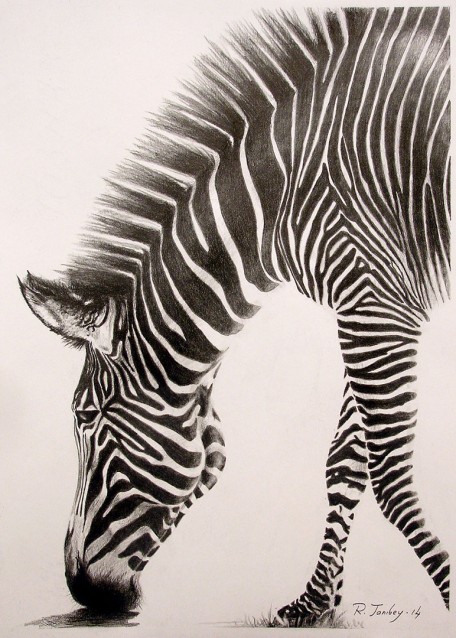

In his paintings, it is noticeable that there isn’t one particular technique that he adheres to. It’s easy, he says, there are paints and brushes, pencil and paper, there are the means and there is my desire to reflect what I’m feeling inside. How I do it depends on what I feel in that moment. I agree, it may not be the most professional approach, but then again, I never claimed to be one.

Just like Rauf muellim many years ago looking at postcards with reproductions of famous works, I too now find myself looking at the spread of his paintings I like the most and wondering how and where he gets his inspiration.

Ideas, themes, visions – these always come in different ways. For example, sitting in a café, or walking in the city, I notice a fragment of a complete stranger’s life, which may connect by association to a very different memory of my own. And sometimes it gives birth to an idea, which may take a while to be reflected on canvas, but will stay within me, waiting for its hour.

And then sometimes it can be totally different: I see a landscape that I like and then “complete” it in my imagination first, and then on the canvas. Or I could be touched by a certain fragment in a book, which I literally start “seeing” in my head, even dreaming about it. Over time I transfer it to the canvas, adding details, associations and emotions.

Nostalgia

One painting in particular attracts my attention, but I can’t recognise the scene. The caption reads, The street that is no more. It suddenly takes me back to my own memories of walking around the side streets of Sovietskaya that always reminded me of small veins connecting it to Baksovet. The old curvy roads, turquoise-domed mosques, two-storey houses with massive balconies, entirely covered with grape leaves. You can hear Azan from afar and smell freshly baked bread from the small window-shop around the corner, where Zeynab khala (aunt) has been selling it for more than 20 years now... and if you close your eyes for a second you can almost go back in time and you’re seven again and life has just begun.

Once again, he explains it with ease: We are mostly affected emotionally by the things that we lose. Usually, we don’t value what we have until we start nostalgically striving for something that is already outside of our grasp, be it health, material goods, friends, parents, or years that flew by too fast. I am as susceptible to these weaknesses as anyone else. All my works are born in my imagination and are a manifestation of my feelings in a particular moment. That, I suppose, is what determines my mood.

He agrees that the image of contemporary Baku has changed a lot in a positive way, but like other Bakuvians of my generation, I miss the friendly, old Baku, without faceless crowds and noisy traffic, he says. The beauty and uniqueness of our city, the Absheron peninsula with its sea, sands stretching to the horizon and funky trees are what inspired him to do art in the first place, whereas the high fences blocking the view to the Caspian, bulky villas, glass, concrete and other innovations kill all inspiration at the bud, leaving you overwhelmed with yearning.

That being said, he also specifies that progress is undoubtedly needed, as we cannot stop time or development: Everything changes - people, human values, cities. What we need is a reasonable reconstruction, without the disruption of the overall harmony and the historical image of the city. Baku is an ancient city which always had its very own individual, inimitable look that should not be radically changed. Applying the experience of European cities, the reconstruction processes need to be natural and harmonious, not turning into something like an abuse of silicone in plastic surgery.

Optimism and Healing

As it would be impossible for a father to choose a favourite child, it is similarly hard for Rauf muellim to single out a favourite painting. There are works that are more or less good in my opinion, then there are those that are more valuable for me, where I’ve invested more of myself, and which have reciprocated. In what way, I wonder...

Every time I look at these works, they communicate with me, bringing consolation, a shield from the worries of the world. And I’m grateful for that, because they fill me with optimism and bring healing, a bit like the goal of my medical practice. In such moments I clearly realise it is true that art is the only lasting trace that a human can leave.

We would need a lifetime to talk about the countless memories connected to the places that no longer exist portrayed in his works. But I can say one thing – I’m proud that those places still exist at least in my paintings, and I hope they will live on even after I’m no longer around.