In the late 19th century the pioneering French traveller, photographer and philanthropist Hugues Krafft (1853-1935) travelled to the South Caucasus with the blessing of Russian Tsar Nicholas II. A selection of his photographs of Baku have recently been on view for the very first time...

During two trips to the South Caucasus, then part of the Russian Empire, Hugues Krafft managed to capture more than 1,000 views of the region (including Azerbaijan) using the most lightweight cameras available at the time. Altogether, 547 of these images are preserved in the archives of the Musée-Hôtel Le Vergeur, the former residence of Krafft in the city of Reims, France. Some of them were recently the focus of the exhibition Discovering Baku – Hugues Krafft’s Journey to the Caucasus.

The exhibition’s curator was France-based Georgian historian Ana Cheishvili, a leading researcher into collections relating to the Caucasus housed in French museums, and its co-ordinator was Ulkar Muller of the European Azerbaijan Society (TEAS), which initiated the project. The launch took place on 24 November with a private view and cocktail party attended by around 60 people, including the ambassadors of Azerbaijan and Georgia to France, H. E. Rahman Mustafayev and H. E. Ecaterine Siradze-Delaunay respectively, and Pascal Labelle, the deputy mayor of Reims in charge of culture. Marie-Laetitia Gourdin, Director of TEAS France, explained the inspiration behind the exhibition:

By looking into the photographs of Azerbaijan archived in these French collections, we discovered the existence of photographs depicting Hugues Krafft’s travels in the Caucasus, and we realised that there were no publications charting his journey to Baku. Tonight, you will discover an exhibition that is the result of research that we have undertaken, the content of which is now being published by TEAS Press in a catalogue of the same name.

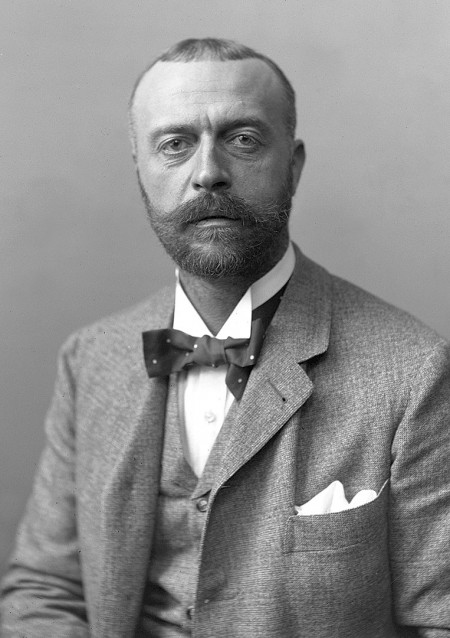

Portrait of Hugues Krafft taken in Tbilisi, Georgia, in November or December 1898. Photo: Collection de la SAVR/Musée Le Vergeur

Portrait of Hugues Krafft taken in Tbilisi, Georgia, in November or December 1898. Photo: Collection de la SAVR/Musée Le Vergeur

Ms Cheishvili, who has previously worked for the National Centre of Manuscripts in Tbilisi and the National Museum of Georgia, has been investigating Krafft’s work for a number of years. In 2016 she gave an extensive interview to TEAS Magazine in which she outlined the archaeological and ethnographic significance of the Caucasus in light of the great 19th-century desire of European anthropological societies to research the origins of mankind:

At this time, the experts began to realise that the Caucasus was the place where the Iron Age began in the 12th–11th centuries BC, whereas in Europe it occurred much later, during the 9th century BC. This led many scientists to undertake missions to the Caucasus. Furthermore, this region is very rich in minerals, and mines were established for various metals, in addition to oil and gas. The explorations were not purely scientific, but also commercial and industrial in nature. Interests in oil, commercial endeavours and science all united to create an enthusiasm for the Caucasus, and provided the finance for missions in the 19th century.

A further source of inspiration for explorers and photographers such as Krafft, noted Ms Cheishvili, were certain contemporary literary works, such as Alexandre Dumas’ Travels in the Caucasus and a travel magazine called Le Tour du Monde.

A wharf jutting out from the promenade in front of Icheri Sheher along the Caspian seafront. Photo: Collection de la SAVR/Musée Le Vergeur

A wharf jutting out from the promenade in front of Icheri Sheher along the Caspian seafront. Photo: Collection de la SAVR/Musée Le Vergeur

Krafft’s visits were facilitated by Tsar Nicholas II who was aware of his work touring the world on behalf of the Société de géographie de Paris for some 20 years. He visited the Caucasus twice, in 1896 and 1898, both times travelling with his friend and fellow photographer Baron Joseph de Baye (1853-1931), who represented the French Ministry of Public Instruction in the Russian Empire. They set off from Marseille and travelled by boat via Constantinople to the Georgian Black Sea port of Batumi. From there they went by train to Tbilisi and onwards over the South Caucasus to Baku, from where they crossed the Caspian Sea to Central Asia. Altogether, 26 of Krafft’s photographs of the South Caucasus were captured in Baku in December 1898, and looking at them today one is able to retrace his steps:

As he sought to discover the city, Hugues Krafft wandered along the wharf on the Caspian Sea, where he photographed numerous porters of various ethnicities. The backdrop to these photographs was the 13th-century Maiden Tower in Icheri Sheher, which is emblematic of Baku. He also photographed the Shirvanshahs’ Palace, including the mausoleum, his photographs being taken many decades before the extensive restoration that heralded the inclusion of the Palace, Maiden Tower and Icheri Sheher on the UNESCO World Heritage List, said Ms Cheishvili.

View from a wharf with the Maiden Tower in the distance. Photo: Collection de la SAVR/Musée Le Vergeur

View from a wharf with the Maiden Tower in the distance. Photo: Collection de la SAVR/Musée Le Vergeur

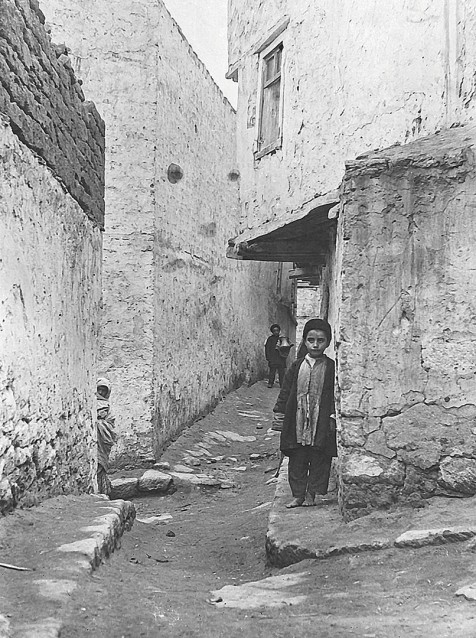

The exhibition is valuable on both a sociological and ethnographic level. As a photographer Hugues Krafft pioneered the use of instant gelatine-silver glass plates and was using the very latest in glass plate cameras, two of which he carried with him on his trip. One was a view camera used for shooting monuments and portraiture; the other was of the photo-binocular type invented by Jules Carpentier (1851-1921), which was relatively lightweight and allowed Krafft to make his reportage-style images of indigenous peoples and sights that have long since disappeared:

Hugues Krafft ranked amongst the first photographers to work in the street, rather than in studios where every element of the image could be controlled. In Baku, he photographed people carrying their briefcases, going about their daily business, and you get a snapshot of their lives which has an ethnographic dimension. In these photos, we can see the history of the country, architecture and culture, said Ms Cheishvili.

A street scene in the old Muslim city of Icheri Sheher. Photo: Collection de la SAVR/Musée Le Vergeur

A street scene in the old Muslim city of Icheri Sheher. Photo: Collection de la SAVR/Musée Le Vergeur

Some of Krafft’s images of the Caucasus were published in a book of his travels called Á travers de Turkestan russe, published by Hachette in 1902, which contained 265 photographs and illustrations and won him wide acclaim, including the Léon Dewez Award, a Gold Medal from the Société de géographie de Paris and the Prix Montyon of the Académie française, as well as a private audience with Tsar Nicholas II. Crucially, however, most of the images recently on show were never published and have not been seen publicly for over a century. Summarising the significance of these photographs, Ms Cheishvili said:

These are views of a vanished world. Hugues Krafft was fully aware of the impact of what we now call globalisation, and sought to capture the everyday lives of peoples in all the countries they visited. In particular, the views of Azerbaijan show a time that predates the dominance of Soviet culture. Hugues Krafft was a remarkable man of his time, and for this reason he was made a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, Chevalier de l’Ordre de Saint-Stanislas and an Officier de l’Instruction publique.

It is important to re-evaluate Hugues Krafft’s views of the Caucasus and, in most cases, exhibit, publish and appreciate them for the first time.

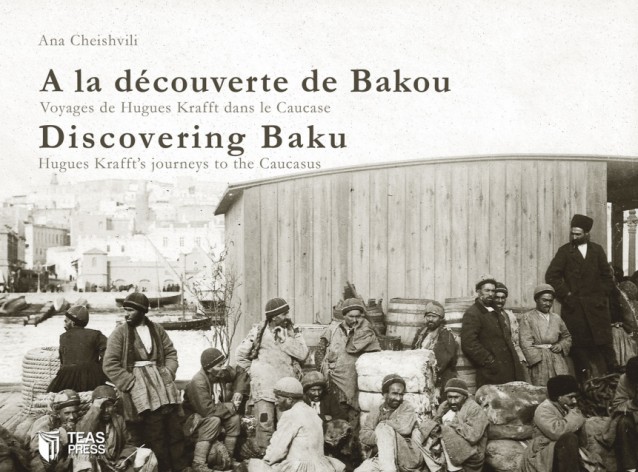

The front cover of the newly published catalogue of Krafft’s photographs of the Caucasus, authored by Ana Cheishvili and published by TEAS Press

The front cover of the newly published catalogue of Krafft’s photographs of the Caucasus, authored by Ana Cheishvili and published by TEAS Press

Discovering Baku – Hugues Krafft’s Journey to the Caucasus was on show at the Musée-Hôtel Le Vergeur in Reims until 4 February 2018.

About the authors: Neil Watson is the former chief editor of TEAS Magazine. Tom Marsden is the editor of Visions.