A few days later I was awoken early in the morning by the sound of the Internationale coming from the streets. I rushed over to the window and saw a great many soldiers that didn’t at all resemble the soldiers of the Azerbaijani national army. They were Russian soldiers. As it turned out, at midnight the revolutionary armoured train had crossed the borders of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic and brought the soldiers of the Eleventh Red Army to the station of the sleeping city. In such a way, without a single bullet fired, the national army of Azerbaijan surrendered. The Republic fell and the victorious Russia once again returned its former property to itself. I saw with my own eyes the end of an entire world!

This is how the Franco-Azerbaijani writer Banine describes the fall of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) in Caucasian Days, her fascinating memoirs of growing up in Baku at the beginning of the 20th century. Banine was the great-granddaughter of two oil magnates, Musa Naghiyev and Shamsi Asadullayev. Her father, Mirza Asadullayev, was a minister of trade in the short-lived ADR, the first democratic republic in the Muslim East which existed between May 1918 and April 1920.

This year marks the centenary of the ADR’s birth and its significance has led President Ilham Aliyev to declare 2018 the Year of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. The success and symbolism of the first republic is being celebrated on a grand scale through films, forums, books and conferences, and even an international football tournament between MPs.

The collapse of the ADR in 1920 ushered in 70 years of Soviet rule, during which discussion of the brief republic became largely taboo. Much of the Azerbaijani elite from the pre-Soviet period had fled into exile (or even lost their lives), where their continuing struggle for independence over the ensuing decades gradually fizzled out. It’s only in the last quarter-century, therefore, that the story of the ADR has increasingly been championed and brought to light.

Confusion in the Caucasus

Its roots are in the latter half of the 19th century, which saw a period of cultural enlightenment, concern about outdated social values and an increasing sense of a national identity among Tatars (Azerbaijanis). These were reflected and popularised in the early years of the 20th century by the likes of Uzeyir Hajibeyov’s operas and musical comedies and the satirical magazine Molla Nasreddin.

The more immediate trigger for the ADR’s foundation, however, was the October Revolution in 1917 and the collapse of the Russian Empire. Parts of Eastern Europe and the Baltics began to declare their independence.

In the South Caucasus, the Transcaucasian Commissariat government was formed in November 1917 and in April 1918 its parliament, the Transcaucasian Seym, declared an independent federation – the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic (TDFR). But this lasted little over a month, bedevilled as it was by disunity between the factions within the Seym over how to deal with Ottoman policy towards the South Caucasus.

On 26 May 1918 the Georgian members declared independence, prompting the Azerbaijani National Council, two days later, to proclaim the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in Tiflis. In practical terms, according to the late Polish-American historian Tadeusz Swietochowski, this had the following hugely significant effect:

So far only a geographical reference, Azerbaijan now became the name of a state, and some 2 million people, called variously Tatars, Transcaucasian Muslims, and Caucasian Turks, officially became Azerbaijanis.

However, in Baku the situation was developing at its own frenetic pace. Here power had been seized by a union between Bolsheviks and Dashnaks (officially called the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, the Dashnaks were ardent supporters of Armenian nationalism – Ed.) and then in April 1918 the Baku Council of People’s Commissars was established, declaring itself an integral part of Soviet Russia.

Thus, when the ADR government moved from Tiflis to Ganja in the middle of June 1918, in essence the territory of today’s Azerbaijan was under dual control, with Baku the stronghold of the People’s Commissars in the South Caucasus and the countryside under the sway of the ADR.

A major turning point for the national independence movement was what’s now known as the March Days, when between 30 March and 3 April some 12,000 Azerbaijanis were massacred by Armenian Dashnak and Bolshevik troops as the ruling Baku Soviet failed to intervene. While this caused Muslims to flee the city en masse, thereby consolidating Bolshevik power, according to Swietochowski, the longer-term impact was this:

After the “March Days” Azerbaijani leaders spoke no longer of autonomy but rather of separation and placed their hopes no longer in the Russian Revolution but in support from Turkey.

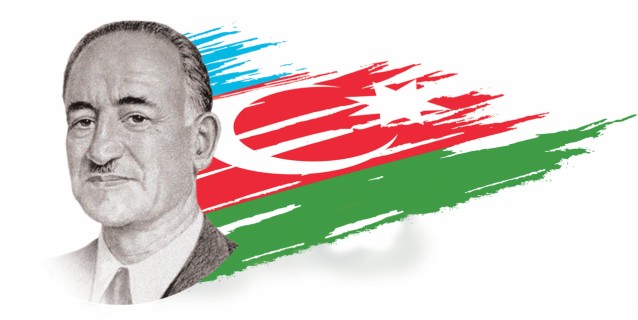

Fatali Khan Khoyski, who served as prime minister in the first three government cabinets of the ADR. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Fatali Khan Khoyski, who served as prime minister in the first three government cabinets of the ADR. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Council of People’s Commissars, led by Stepan Shaumyan, subsequently set about nationalising the banks and the oil fields. But due to growing food shortages and general unpopularity this government only lasted until the end of July when 26 of its commissar members were arrested. The story of their subsequent flight and execution later became a powerful Soviet legend.

The Council was replaced by the Centro-Caspian Dictatorship, which fared little better and capitulated itself on 15 September when Baku, poorly defended by disorderly Armenian soldiers supported by a small British contingent known as “Dunsterforce,” was liberated (following a three-week siege) by the Caucasus Army of Islam. This was a coalition of Turkish and ADR troops that had formed following the Ottoman-Azerbaijani peace and friendship treaty signed in Batumi on 4 June 1918.

In such a way, a few days later the ADR was able to move its capital from Ganja to Baku.

Keep calm and carry on

Besides the battle for Baku, another major challenge for the ADR was negotiating border disputes and in particular resisting Armenian claims to Nakhchivan, Zangezur and Nagorno-Karabakh. Establishing and securing the new state’s borders remained one of the government’s top priorities throughout 1918 and 1919.

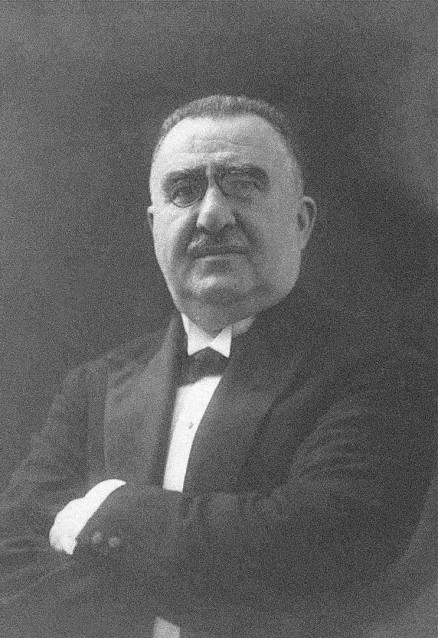

A major role in this was played by the Azerbaijani delegation, led by Ali Mardan bey Topchubashov, dispatched to the Paris Peace Conference, where despite meeting initial resistance it succeeded in getting the entente powers to recognise the ADR’s de facto independence on 11 January 1920. The delegation’s tumultuous journey is the subject of Eternal Mission (2016), a film produced by Arzu Aliyeva and supported by the Heydar Aliyev Foundation which is likely to be screened widely this year. By April 1920 over 20 countries had diplomatic representations in Baku.

The ADR’s diplomatic achievements are all the more praiseworthy given foreign powers’ interests in Azerbaijan’s strategic location and oil resources. As one history teacher in Ismayilli recently summarised to Visions, at that time, Azerbaijan was an apple of discontent between Turkey, Iran, Russia, England and France.

Domestically too, the ADR did far more than simply exist. Over 23 months, five government cabinets were assembled (the first three under Fatali Khan Khoyski; the following two under Nasib Yusifbeyli). Parliament was located in the building of today’s Institute of Manuscripts, outside of which now stands a monument inscribed with the ADR’s declaration of independence, and its composition set the tone for the republic’s tolerant, Western-leaning vision. A cross-section of nationalities was proportionately represented, including: Turks (Azerbaijanis) – 80 seats; Armenians – 21; Russians – 10; Germans – 1; Jews – 1; Georgians – 1; Poles – 1. In total, 145 parliamentary sessions were held and some 230 laws passed. Another well-cited fact is that women were granted the right to vote ahead of many countries in the West.

Other innovations aimed to equip the ADR with all the attributes of a genuine state. An army was formed, a central bank and currency launched and, alongside Russian, Azerbaijani (Turkic) became the state language and language of education. Other educational achievements included the founding of Baku State University (BSU) where lectures began in November 1919, making this the first higher education institution in Azerbaijan. A government programme also sent 100 talented students to study in France, UK, Italy and Turkey during the 1919-1920 academic year, many of them never returning to Bolshevik-occupied Azerbaijan.

Fall & legacy

By the beginning of April 1920, the fifth government cabinet had collapsed and the ADR was facing an internal political crisis, as well as mounting pressure from Soviet Russia. The Bolsheviks were desperate to get their hands back on Baku oil and felt encouraged by the support of Kemal Atatürk’s Turkish national liberation movement, which sought Soviet assistance in its battle for Turkish independence.

Further complicating the situation was an Armenian uprising in Khankendi, Nagorno-Karabakh, in late March, which had forced the ADR government to redirect troops from its northern borders and leave them largely undefended. Moreover, the Communists, who had become more unified throughout early 1920 and gained support in Baku, were unwilling to cooperate with Parliament, making the formation of a sixth cabinet impossible.

On the night of 27 April troops of the Eleventh Red Army crossed into Azerbaijan and, realising the hopelessness of the situation, Parliament voted to hand over power to the Provisional Revolutionary Committee headed by Nariman Narimanov. With this came the end of the “entire world” witnessed by the young Banine above.

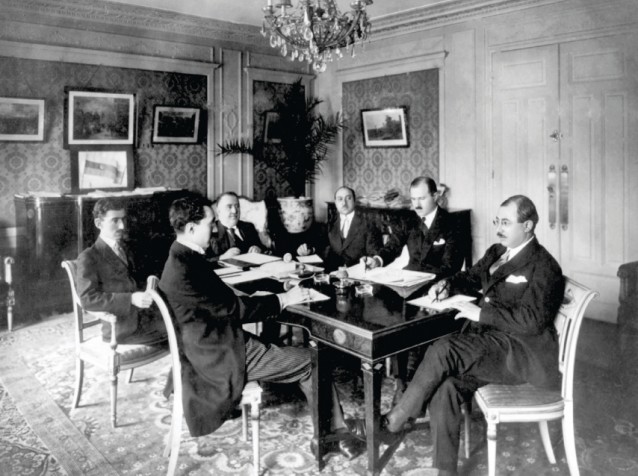

Ali Mardan bey Topchubashov, the ADR’s foreign minister and head of the ADR delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919-1920

Ali Mardan bey Topchubashov, the ADR’s foreign minister and head of the ADR delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919-1920

Another classic book exploring the period is Ali and Nino, which beautifully captures the spirit of the time, the yearning for independence versus the vulnerability of the fledgling state, as well as the mystery and multiculturalism of the Caucasus. It’s symbolic that following the Bolshevik seizure of Baku, the hero, Ali, meets his end defending Ganja from the invading Red Army. The life of our Republic has come to an end, as has the life of Ali Khan Shirvanshir, reads the concluding note by Ali’s loyal companion Ilyas Bey.

Having restored independence in 1991, the new Azerbaijani republic adopted the ADR’s tricolour flag and national anthem (composed by Hajibeyov), Soviet monuments were gradually replaced by those of Azerbaijani national heroes and geographical names changed or restored. If the ADR had been the apogee of the growing national consciousness among the Muslim Turks of Transcaucasia at the end of the 19th, beginning of the 20th century, the new republic sought to build upon the same ideas.

President Ilham Aliyev suggested as much when signing an order to declare the national theme for 2018, while also cautioning against drawing too many parallels. According to apa.az, he said:

Today’s Azerbaijan, an independent Azerbaijan, is the heir to the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. We are committed to all the democratic traditions of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic and we live in these traditions. But I should also note that today’s Azerbaijan cannot be compared with the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Because at that time there were difficulties and our independence did not allow Azerbaijan to pursue an independent policy. We had economic difficulties, land losses, and our historical city Irevan was given to Armenia. Therefore, we have to properly analyse the activities of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.

Today, the ADR is often remembered in Azerbaijan not simply as the first Azerbaijani republic, but also as a symbol of freedom from foreign rule – It was the first time that we could control our own resources, one young professional recently summarised to Visions.

Perhaps more important, however, was its contribution to Azerbaijani identity: It [the ADR] is sacred. Being Azerbaijani, it’s how we found out who we were, a Baku-based linguist elaborated.

The first republic is remembered every year on Republic Day on 28th May. This year’s celebrations are likely to be doubly profound.