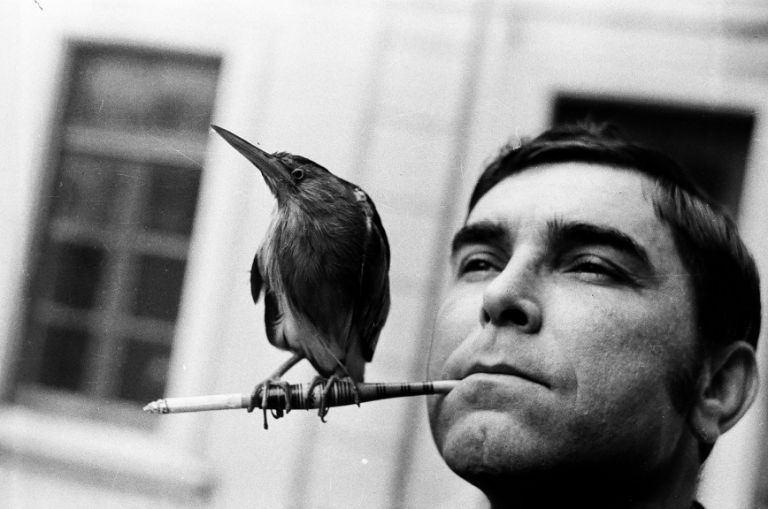

Akif Agayev isn’t around anymore, but his photos are. And here is one of them. In it is a middle-aged man. He is dressed in black, wears a flat cap which residents of the Absheron peninsula for some reason call an aerodrome. The half-smoked cigarette in his overworked hands seems tiny, and the sadness in his eyes – immense. His hands know what to do. They need to plow, plant, peel, dig ... And again: plow, plant ... to reap the fruits. But then why has melancholy crept into his eyes? Why is it so painful to look at the silent grief of this man? I feel uneasy looking at his restless gaze. After all, we were promised: simple daily labour will wipe away the rhetorical questions, but here...

The victory over fascism in World War II brought to life the concept of humanistic photography. In their work, the photographers of this wave, which arose in the middle of the last century, repeatedly confirmed that creative good is stronger than irrational evil. Akif Agayev may not have been acquainted with representatives of humanistic reportage – the emotional photos of Marc Riboud, Willy Ronis, Robert Doisneau. Yet, his works are permeated with humanism, or rather humaneness.

A click, and what seemed elusive acquired immortality! Akif Agayev was capable of this magic, even though he modestly called himself an amateur

Born. Lived. Photographed.

What does an author do when he starts writing a biographical essay? Armed with curiosity, as if it were a plow, he furrows the uncultivated (uncharted) pages of the hero’s life. He carefully examines the underesearched areas, double-checks the dates, sifts out the key episodes, and brings to light (if lucky enough) the sensational facts. Anticipating the possible discontent of the reader, I will inform: the author of this essay hasn’t found any spicy details. I’ve simply dug up a lot of photos. Monochrome. Eloquent. Priceless... But more on this later.

Akif Agakishi oghlu Agayev was born in Baku in 1946. He studied to be a philologist. He worked in major publishing houses across the country. He was head of the press service of the Caucasus Muslims Office. He became a father. He raised a daughter and son. He was fond of making images, as many others were in the Soviet years – the years of thaw, stagnation and unrealistic hopes... Photography at the time of technical innocence seemed after all a form of magic. Here is a piece of white paper, and not even a minute will go by before faces appear on its surface, the frozen smiles of people – loved ones, strangers, photogenic and not so much. Many people took a great interest in photography, but only a few stayed faithful. However, there were those who managed to capture a moment of life, and not just any moment, but a split second full of meaning. A click, and what seemed elusive acquired immortality! Akif Agayev was capable of this magic, even though he modestly called himself an amateur.

(Just to think that nowadays the time from releasing the shutter of a camera, or other gadget, to publishing the “photo” on the web is just seconds!).

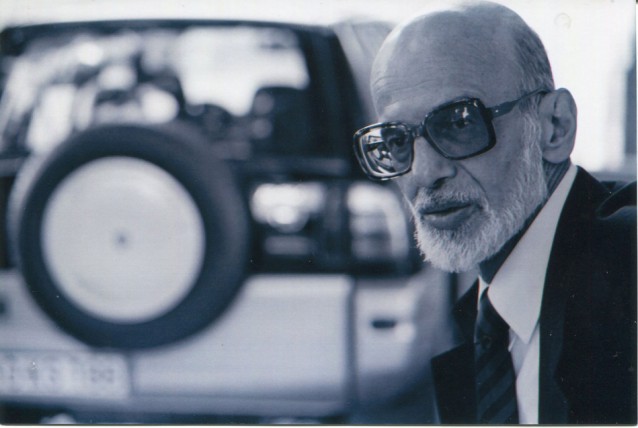

Test prints

Reviewing the photos of a talented photographer is like reading an engrossing book. To study a portrait captured by such a master is to get acquainted with the biography of the subject of the picture. Akif Agayev’s portfolio includes dozens of such narrative portraits. For objectivity’s sake, it’s worth adding that there are works of different genres there. Landscapes, newspaper reports, city observations similar to short, succinct haiku... Works testifying to a search for one’s own theme, one’s very own intonation... But portraits occupy a significant place in Akif Agayev’s archives. They aren’t made in the scenery of photo studios, but in an unpredictable reality. It’s not the flattering combination of thoughtful lighting that emphasises the faces of his models, but the natural light of the sun or the “milk” of the cloudless sky (“milk” is a slang term used by cameramen to describe the lighting mode in cloudy weather). It isn’t human mannequins frozen in spectacular poses that look at the viewer in these frames, but characters, stories and small lives.

Akif Agayev’s photos speak for him and more – they tell us what can’t be expressed by any words

Outtakes

Regulars of the Union of Photographers remember Haji Akif (Agayev adopted this title after his pilgrimage to Mecca) addressing young photographers with the words: Keep going! You have a good eye! These words spoken sincerely, by a man whose appearance was so reminiscent of a wise old man, instilled confidence and encouraged young people to try new experiments. They had the effect of a pep talk, which are given sparingly by those in creative professions.

Unnamed photo vers libres

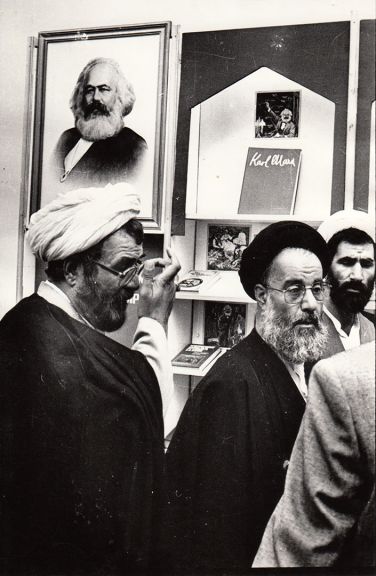

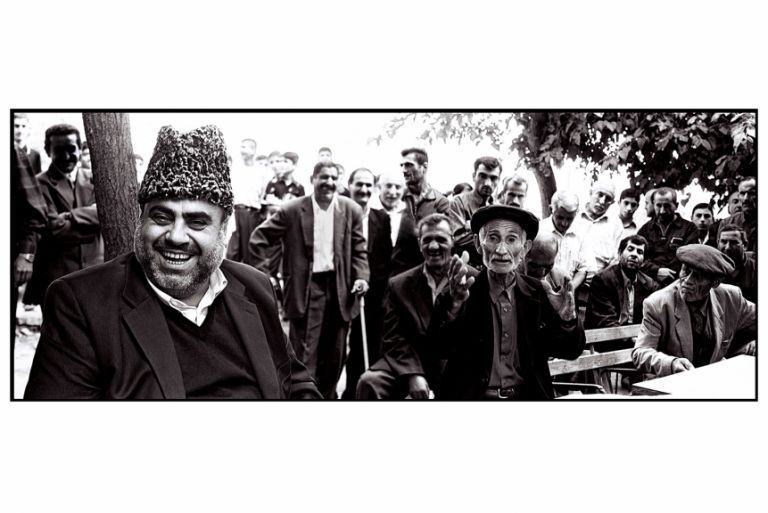

Agayev’s works aren’t captioned. There’s no name for the portrait of the red-haired boy blinking at the sun, smiling... The photograph of the Iranian sheikhs peering into the books of Karl Marx is also unnamed. There’s no name either for the picture in which the head of the Caucasus Muslims Office, Haji Allahshukur Pashazadeh, appears not according to strict protocol, but laughing. Perhaps at a joke made by one of those old-timers parked in the shade of a sprawling tree, in the depth of this brilliant composition.

“Sun Boy,” “Irony of Contrasts,” “The Sheikh and his Flock”... But you can cross out all these suggested names, forget them and offer your own, because the eloquent creativity of Haji Akif allows for that.

Video ergo sum

Some skilled photographers examine the sensual nature of colour, others explore the magic of light. Some see the highest manifestation of truth in ordinary life, while for others the prose of daily routine appears in a poetic guise... Which of the above is closer to the hero of our article? Is he a lyricist or is he far from romanticism? Does he merely record the facts or the metaphysics of existence? Is having someone in the viewfinder important to him or is a person just a desired addition to the frame? Is he a slave to geometry or is impeccable composition found in the reality around him? Let’s leave these questions unanswered. Surely, you’ll also agree that trying to dissect the essence of a work will actually take away its mystery – it’s vulgar and meaningless. It would be more honest just to look and be intoxicated by them. It’s worth adding simply: Akif Agayev’s work invites not only contemplation but also empathy for the heroes of his monochrome stories.

Man pro man

To the idle viewer a successful journalistic photo often seems the result of a lucky coming together of circumstances. However, the portfolio of our hero leaves no doubt that what we see before us is the result of genuine creativity, because it’s obvious – there’s no place for luck here.

Discovering the works of Akif Agayev generates a semblance of insight – the realisation of a simple truth: for a photojournalist to be lucky at “decisive moments” (“the decisive moment” was the guiding principle of photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson), they have to be extraordinary. And they need not to look, but to see. More than to see – to scan. More than just to scan, but to empathise. Empathising, to keep their distance and not fall into excessive sentimentality... All this is essential in order to catch a miracle. To capture that decisive moment.

Akif Agayev looked at the world sympathetically, he noticed the glimmers of good in people, and elicited the spiritual grace of human nature on the surface of his monochrome frames. This is exactly why in his case the overused word “humanist” begins to sing.

True, we didn’t have the chance to meet when he was alive, but, after all, as the poet Stefan Mallarme once said: Look at what I see, not at me. Akif Agayev’s photos speak for him and more – they tell us what can’t be expressed by any words.

About the author: Nonna Muzaffarova is a scriptwriter, director of documentary films and a member of the Azerbaijan Union of Filmmakers. She also writes for Nargis magazine and the Russian magazine Prochtenie.