The original of this article appeared on French website footballski.fr on 5 January 2018. Visions has kindly been granted permission to reprint a translation by Neil Watson of the original French version.

21 November 1965: The Maracana Stadium played host to a friendly match between Brazil and the USSR. Receiving the Soviet team was a real event in the land of football. It was only the third time that the two nations had come up against each other. Filled with 123,000 spectators, and with Senator Robert Kennedy present, the Maracana saw the Seleção leading at the beginning of the second half thanks to goals by Gerson (51st minute) and Pelé (54th minute), who managed to fool goalkeeper Yashin with a beautiful strike, of which only he knew the secret. The spectators were ecstatic when, in the 59th minute, one man sounded the Soviet revolution. Anatoliy Banishevskiy, a 19-year-old striker, who was developing at the Neftyanik Baku club, capitalised on a bad restart from goalkeeper Manga to return the ball from 30 metres out into the bottom of the net.

For several seconds, the terraces were plunged into silence, coming to terms with what had just happened, then they exploded when hearing the name of the scorer. Pelé stopped and looked at me with a petrified expression. He didn’t know that 25 minutes later Slava Metreveli would put the teams level. One of the leading Brazilian newspapers at the time described my goal as the “goal of the decade.”

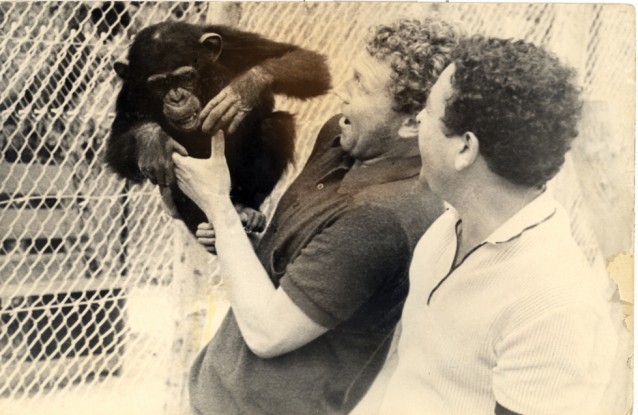

Banishevskiy in action for Neftchi, the club he represented throughout his career (1963-1978). Photo: courtesy of Neftchi PFC

Banishevskiy in action for Neftchi, the club he represented throughout his career (1963-1978). Photo: courtesy of Neftchi PFC

It is impossible to find this goal on video, as none of the cameras were expecting a goal at that moment, especially not one like that. However, it was this goal that became synonymous with his career and he remains in history as the first Soviet footballer to score against the Brazilian national team, at none other than the Maracanã!

An explosive rise

To summarise Anatoliy Banishevskiy with this goal would be a mistake. What stands out from his biography is his unconditional attachment to Baku. Born in the Azerbaijani capital on 23 February 1946 into a family with roots in western Ukraine, the young Anatoliy began his career in an explosive manner. Spotted playing on a pitch for children by Locomotive Baku, “Banya,” as he came to be known by his teammates, exploded onto the scene by racking up goals in his first three seasons. Neftyanik Baku didn’t wait long before recruiting him in 1963. The team was then under the orders of Boris Andreyevich Arkadyev, who sung his praises thus:

A young boy who we will hear about soon is in the process of developing with us. This boy is intelligent, decisive, and terrifyingly good at football. His youth means he needs further polish, but soon he will be ready and will become a striker with the grace of God.

And soon he ascended to the next level as the following year he joined the first team, which was then making progress in the Soviet Union’s premier division, and played his first match in the Soviet Top League at the age of 16.

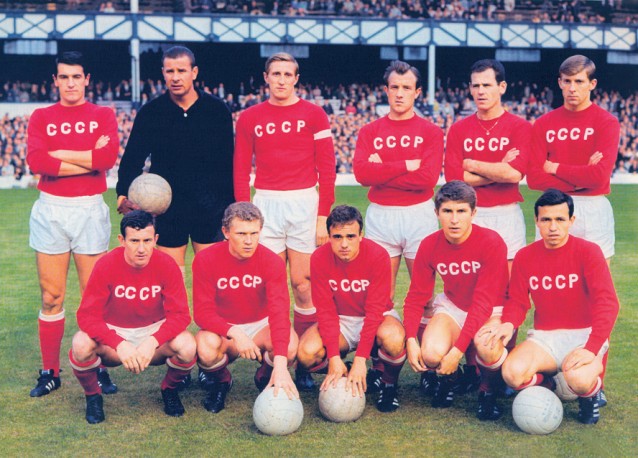

The USSR side that finished fourth at the 1966 World Cup in England. Banishevskiy is pictured in the front row, second from left. The photo was taken before the team’s semi-final match against West Germany at Goodison Park. Photo: courtesy of Neftchi PFC

The USSR side that finished fourth at the 1966 World Cup in England. Banishevskiy is pictured in the front row, second from left. The photo was taken before the team’s semi-final match against West Germany at Goodison Park. Photo: courtesy of Neftchi PFC

It was a rapid progression also with the Soviet national team, after being selected by Nikolai Morozov at the age of 19. The selection of this “kid” was criticised in the media of the time, irked by the youth and inexperience of Banishevskiy. Despite that, he demonstrated all of his attacking qualities by scoring seven goals in eight matches. He also participated in the 1966 World Cup in England, during which he scored against North Korea. He was in the Soviet Union’s starting line-up throughout the entirety of the World Cup, which they finished fourth following defeat against Eusébio’s Portugal (2–1). However, this wasn’t bad for an inexperienced “kid” of 20.

The year 1966 was the summit of his career, and coincided with the pinnacle of Azerbaijani football. Effectively, Neftchi, the principal club in the Azerbaijan SSR reached the podium of the Soviet Top League, finishing third, the best result in the history of Azerbaijani football in the Soviet championship. Surrounded by the greatest Azerbaijani players of the era – Kazbek Tuaev, Aleksandr Trophimov and goalkeeper Sergey Kramarenko – Anatoliy Banischevskiy registered 19 goals in 51 matches in the championship.

What difference did it make where I could play? I never would have wished to play anywhere other than Baku

In Baku and nowhere else!

His performances didn’t go unnoticed during the era, notably after the 1966 World Cup when certain English clubs expressed an interest in signing him. The German company Adidas proposed a contract worth half a million dollars for his services, but the Iron Curtain was incompatible with taking part in various advertising campaigns.

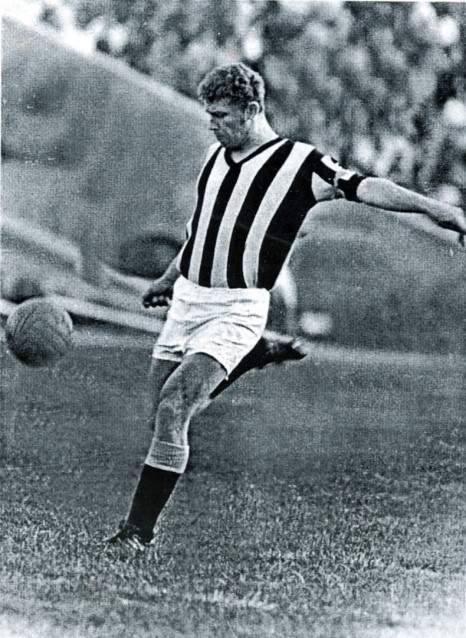

Banishevskiy won 50 caps for the USSR national team between 1965 and 1972. Here he is playing for the USSR against Switzerland in 1967 (left). Photo: courtesy of the National Photo and Film Archives of Azerbaijan

Banishevskiy won 50 caps for the USSR national team between 1965 and 1972. Here he is playing for the USSR against Switzerland in 1967 (left). Photo: courtesy of the National Photo and Film Archives of Azerbaijan

But, contrary to certain others, Anatoliy Banishevskiy didn’t oppose the restrictions of the Soviet authorities on leaving the country. He quite simply had no desire to leave Baku. What difference did it make where I could play? I never would have wished to play anywhere other than Baku, he later said. This city suited him in every respect and the idea even of settling in the capital, at the big Moscow or Ukrainian clubs, which were pressing for his services, didn’t interest him at all. Vladimir Ponomarev, then a player for CSKA, recalled:

Anatoliy and I were opponents on the pitch, but friends in life. It was impossible to argue with him because he was so kind. In his time, Anatoliy Banishevskiy, was the most dangerous striker after Eduard Streltsov. All the Moscow clubs wanted him, but he would never leave Baku. I recollect that, in 1969, the CSKA trainer Vsevolod Bobrov and I managed to persuade him to come. The club had prepared a three-bedroom apartment for him but in the end he never landed in Moscow.

One of the most celebrated Azerbaijani players therefore stayed in Baku throughout his career. There he was a major striker in the Soviet championship at the end of the 1960s. Notably, he made the list of the 33 greatest Soviet footballers of the season, finishing second in 1965, 1966 and 1967 and becoming a member of the Grigory Fedotov Club which brought together the several Soviet players to have scored over 100 goals during their careers.

Banishevskiy lining up for Neftchi at the Tofiq Bahramov Stadium (then the Lenin Stadium) in a Soviet championship league match in 1975. Photo: courtesy of Neftchi PFC

Banishevskiy lining up for Neftchi at the Tofiq Bahramov Stadium (then the Lenin Stadium) in a Soviet championship league match in 1975. Photo: courtesy of Neftchi PFC

Disturbing behaviour

Despite this booming start to his career, what followed wasn’t as illustrious as envisaged due to behaviour off the pitch that didn’t comply with the obligations of a sportsman. In 1971, “Banya” was close to being dismissed along with five other Neftchi players for serious violations of sporting discipline. It was only with the intervention of his most powerful support in the form of First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Azerbaijan SSR Communist Party Heydar Aliyev that he was able to get away with only a simple warning. However, these disciplinary incidents culminated in 1972 during the final of the Euros. The USSR returned to the changing room having suffered a serious 3–0 defeat against Gerd Müller’s West Germany. Anatoliy Banishevskiy recalled:

We lost with a score of 3–0. After the match, an important sports official entered the changing room and gave us a telling off. Treating us as traitors to the motherland, I ended up cracking and responded to him “If you don’t like how we play, you should have come on the pitch and shown us how to do it.” The visitor turned and left the changing room. I was never called up to the national team after that.

during those few scraps of time he could change the course of the match all by himself

After returning to Azerbaijan, he was considered one of the main culprits for the defeat. Nothing was the same after that, not even at his club where he barely played anymore. At one point he stopped playing football altogether up until 1976, the date when he returned to Neftchi. Incapable of playing 90 minutes due to his troubles with alcohol, he came on sometimes right at the end of the match, cheered by the crowd, and during those few scraps of time he could change the course of the match all by himself. But by then his physical condition was letting him down and it was in such a way that two years later he put an end to his playing career.

A bunch of fatal illnesses

Following that, he attempted a career as a coach with several clubs during the 1980s. Between 1981–83, he took the reins of the club closest to his heart, Neftchi, but the idyll didn’t last long due to differences of opinion with the directors. Despite the illness that took hold of him (he was plagued by diabetes for a long time) he left to train the Burkina Faso national youth team. But there Banishevskiy had to face significant political tensions, notably a coup d’état in October 1987. Also suffering with pancreatitis, attributable among other things to excessive alcohol consumption, he returned for good to the USSR. His health rapidly deteriorated and he ended his life almost in misery. He died on 10 December 1997 at the age of only 51.

His candidness ultimately got the better of him. Banishevskiy will remain in Azerbaijani memory as one of the greatest footballers in their history. In 1991, during a ceremony to celebrate 80 years of Azerbaijani football, homage was paid to Banishevskiy by awarding him the title of Great Master of Soviet Sport that he had been stripped of following the Euro ‘72 defeat. This was one way to show that despite his behaviour or lifestyle, Banishevskiy was a very talented player.

About the author: Vincent Tanguy is a French football writer who lived in Moscow for nine years and became a fan of Soviet and Russian football. He is a contributor to the French website footballski.fr on Eastern European football and also writes for the English website russianfootballnews.com.