It [Gedebey] is the thoroughly European spectacle of a small picturesquely situated manufacturing town, which presents itself to view, with huge furnaces and large buildings, among them a Christian chapel, a school, and an inn fitted up in European fashion (Personal Recollections of Werner von Siemens. 1893, p.280.).

When I received a job offer to work in the Gedebey Copper and Gold Mine in 2012, I was told I’d spend half my time in Baku and the other half in Gedebey. But I ended up living and working in Gedebey for two years as an interpreter and supervisor for the construction of the largest tailings dam in the South Caucasus.

The construction manager always talked proudly at the site about the fact that our work would leave traces here that would still be visible by satellite for a thousand years. That gave me the passion to do the job, but it wasn’t enough to get me excited about living in Gedebey.

To live there I had to find a non-work-related reason. So I dived into researching Gedebey’s historical sites: its medieval castles and Christian monasteries, Bronze Age Cyclopean masonries, as well as the heritage left by the Siemens brothers from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Satellite images from Google Earth proved to be a practical tool for spotting anomalies in the natural landscape. It was one of those ordinary days when I was checking the satellite images of the arch-bridge (also called a viaduct) in the village of Duzyurd... Suddenly I was shocked:

Ohh look here, another one. Wait a minute... there’s a trace... it connects those two. Oh God, the trace leads from one to another and then to another one there.

I tracked the path. It dragged me all the way to Galakent. I tracked it in reverse. It took me to the mine in Gedebey. Then it led me 130 years back in time.

Background

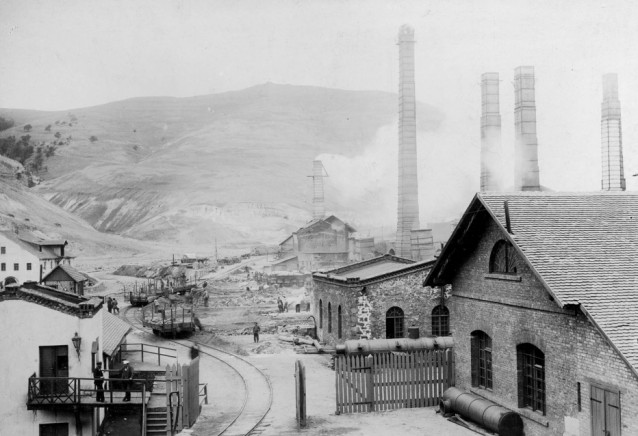

In Gedebey, there were copper smelting plants and a copper and gold mine which were operated by the Siemens brothers from 1865 to 1920. The Siemens brothers – Werner, Carl, Walter and Otto – privately owned mining operations at the mine on Mis Dağı (Copper Mountain) and the smelting plant in the southeast of the city (currently on M. E. Rasulzade Street).

The mining industry in Gedebey turned into a lucrative business in the 1870s when the Siemens brothers used the latest innovations and technologies of the time to maximize copper and gold production there.

As the financial profit increased, the brothers were able to grow the industry in 1883. The scale of operations was also expanding due to projects such as the Indo-European Telegraph Line, which stretched from London to Calcutta across the Eurasian continent. Business grew to such an extent that they decided to construct a second smelting plant.

Galakent, a village to the southwest of Gedebey, was chosen as the location for the new plant, which had to cope with challenges related to its isolated location, such as the lack of an energy source and its distance from the mines.

The Siemens brothers decided to use the electrolytic method of refinement at the Galakent plant, a method that had already been successfully marketed in Great Britain. The electrolytic method of gold and silver plating was actually the first patent that Werner von Siemens, the founder of Siemens, was awarded in 1842. In the electrolytic method, you put the impure gold and another sheet of pure gold into a specific liquid solution. When you run an electric current through the solution, molecules of pure gold separate from the impure substance and are deposited onto the pure gold sheet.

A new smelting plant

The remoteness of Gedebey proved to be too difficult to import oil, and local wood resources were also falling short of meeting demand given the increasing volume of operations. So a more efficient approach had to be found to address the issue of energy resources. The electrolytic method would allow the Siemens brothers to use efficient local energy resources for smelting copper.

The brothers were aware of the potential of hydropower in Galakent. In order to run an electrolytic smeltery plant, they had the idea to convert the energy of water running downstream into electric current by building an affiliated hydroelectric power plant, which they did the same year. In such a way, the plant received a supply of electric current as a local source of sustainable energy to run the smelting operations.

Nonetheless, there was another unresolved issue: the mine in Gedebey and the plant in Galakent were about 30 km apart. There wasn’t a developed transport connection, beyond a walking path. But a proper transport connection was needed in order to transfer the ore from the mine to the plant in Galakent, as well as to deliver the refined minerals back to Gedebey. The proposed solution was to build a railway, or, more precisely, a narrow-gauge line.

In 1879-1883 the Siemens brothers completed the railway connection between the Gedebey mine and the copper smelting plant in Galakent. The Gedebey-Galakent railway was one of the first railways of its kind in Azerbaijan (the Baku-Sabunchu-Surakhani line had already been in operation since 29 April 1880) and the South Caucasus.

The railway also travelled through the villages of Miskinli, Chaldash, Duzyurd, Sabatkechmaz, and Chalburun. The exact length of the route is unknown, but some claim it to be 28 km, others – over 30 km. The most reliable reference would be Werner von Siemens himself. He defines the length as some twenty miles (32 km) in his memoirs.

There is also a railway carried over a lofty viaduct, connecting the branch smelting establishment of Kalakent, some twenty miles off, with Kedabeg and the neighbouring metalliferous mountain. (Personal Recollections of Werner von Siemens. 1893, pp. 280-281.)

A legend?

There is a legend among the engineers of today’s Gedebey Gold and Copper Plant about how the Germans used a mother donkey to design the railway route. The story goes that the Germans brought the foal to Galakent and the mother to Gedebey, then followed the mother as she sought her newborn baby, meanwhile drawing a line. This line later became the route for the railway.

Whether the story is fact or fiction, the route has a brilliant design. It is on a perfect slope: the mine’s location is higher while the Galakent plant is lower in altitude. So it has a slight and gradual incline with easy going along the route.

The landscape of the route is complex. It goes through mountain stream valleys and hard rock on mountain ridges. The Germans built arch-bridges (viaducts) to overcome the downstreams. The largest bridges have seven or eight arches. Two of the large arch-bridges are located in Chalburun, three in Sabatkechmaz and one in Duzyurd.

On the ridges, they had to cut through hard rock with the technology they had at that time. Such hard rock cuts are located in the villages of Chaldash, Chalburun and Sabatkechmaz. The cuts in Chalburun are noteworthy for the accuracy of the work on the ridge.

Having spotted the route on Google Earth, I went to Galakent in order to experience its entirety from one end to another. I walked through each village and examined every arch-bridge along the route. In the village of Sabatkechmaz, I accidentally found one of the railway base-plates lying on the slag-covered ground.

Today, one can observe the ruins of 23 arch-bridges to various extents on the route. Some of the bridges are the same as they were 100 years ago but most of them are in a critical condition. The impact of water erosion and human-related destruction is playing a big part. Some of them have already collapsed and washed away. However, the columns and remnants of some bridges lay in the stream bed; Sabatkechmaz has the best example of one of those collapsed bridges.

The arch-bridge in Duzyurd is infamously called Qanlı Körpü (which literally translates as “Bloody Bridge”). The reason why people call it this is because of a deadly crash in which wagons fell off the bridge killing all the people on the board. The section of the route between Galakent and Duzyurd (until the last bridge in Duzyurd) is visible from the satellite images; the long curved line continuously travels through the villages and is easily recognizable.

The route had an extension to the southeast of Gedebey where major smelting infrastructures were located. In the city centre, I walked through every street. To my surprise, I found that there are still many buildings and structures that remain as you see them in photographs of the old days. If you take a walk along Rasulzade Street, you can witness the ruins and remnants of those.

Unfortunately, modern urbanization has changed the landscape all around the city of Gedebey. It is impossible to determine the exact path of the route that went through the town. Even so, you can still observe dormant bridges, ore and slag waste in the southeastern part of the city, where the smelting plant is located.

With its imperfection, simplicity, the engineering mastery of the Siemens and the mystical stories yet to be revealed, Gedebey is a forgotten yet must-see place in Azerbaijan. The Siemens heritage and the Gedebey-Galakent railway route remain at the centre of the essence of Gedebey.

About the author: Gani Nasirov is the founder of Baku Original Walking Free Tours and is currently developing new routes for tourists, including a food tour. He also writes a travel blog at www.thetravelguidebaku.wordpress.com.