Dr Michael A. Reynolds is an associate professor of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University and the author of Shattering Empires: The Clash and Collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires 1908-1918, a widely acclaimed examination of the rivalry between these two vast empires whose fall at the end of the First World War continues to shape the South Caucasus today.

In the next article of our series marking the centenery of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR), Visions took the opportunity to ask Dr Reynolds a few questions following his recent lecture tour to Baku. Those we posed were in response to a fascinating talk on The Geopolitics of the Birth and Death of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.

VoA - What was the situation in the South Caucasus in 1917 after the fall of the Russian monarchy?

MR - The situation in the South Caucasus in the wake of Tsar Nicholas II’s abdication was one of great confusion and uncertainty. The Russian Empire in 1917 was a geographically immense and sprawling entity with a complex, modernizing society in flux and under great strain, and a dynamic and rapidly growing economy. At the same time, it was governed by an archaic and unwieldy system that revolved around the person of the tsar. Thus although the empire was host to a sophisticated, developing society and a powerful, dynamic, and growing economy, the thing holding it together as a single entity was the monarchy. The tsar was the lynchpin of the system, and so once he stepped down, the whole thing began to unravel despite the fact that the largest and most important political actors wanted to hold it together and restructure it on a democratic basis. This proved difficult, and the rise of the Bolsheviks made it impossible.

This process of administrative breakdown and degeneration manifested itself in the South Caucasus immediately. Thus, for example, when the tsar abdicated, his viceroy in the Caucasus, the chief administrator of the region, had to step down, because if there was no tsar, what logic could justify maintaining his representative in any official position? An essentially ad hoc administration that called itself the Special Transcaucasian Committee replaced the viceroyalty. But with the Russian capital preoccupied with sorting out its own problems (all the while also trying, and failing, to prosecute an unpopular war), the South Caucasus after March 1917 was left to look after its own affairs and exist in a state of de facto independence.

Further adding to the confusion in the South Caucasus was the dissolution of the Imperial Russian army as soldiers abandoned it in droves and the rise throughout the region of radical councils, soviets, of workers and soldiers. Led by the Bolsheviks, these soviets undermined the authority of the Special Transcaucasian Committee in Tiflis (Tbilisi).

How did this change following the October Revolution?

The Bolshevik seizure of power on 7 November clarified matters to the extent that it presented something that virtually all non-Bolsheviks in the South Caucasus could and did reject. In response they formed the Transcaucasian Commissariat to replace the Special Transcaucasian Committee. The basic idea was to reject the Bolshevik claim to power and wait until the all-Russian Constituent Assembly was supposed to convene in January 1918 and decide how to restructure the Russian Empire along democratic lines. The leading Transcaucasian political parties, the Mensheviks, the Dashnaktsutiun, and the Musavat, all remained loyal to the vision of the February Revolution.

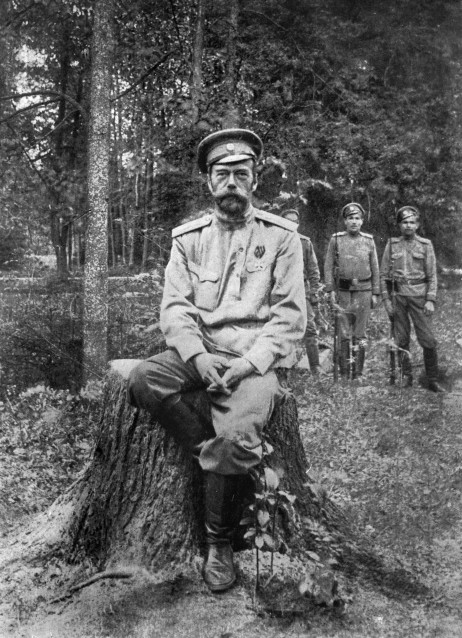

Tsar Nicholas II photographed in March 1917 at Tsarskoye Selo following his abdication, which created an uncertain situation in the South Caucasus. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Tsar Nicholas II photographed in March 1917 at Tsarskoye Selo following his abdication, which created an uncertain situation in the South Caucasus. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

But in foreign relations the Bolsheviks’ coup d’etat, or perevorot as the Bolsheviks themselves described the October Revolution, further confused matters. In negotiations with the Ottomans, the Transcaucasians tried to have it both ways on the question of independence from Russia. They rejected Ottoman entreaties to declare their independence and sign a peace treaty, insisting that they remained part of a greater Russia. But when the Ottomans presented them with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, wherein the Bolshevik government of Russia effectively relinquished the provinces of Kars, Ardahan, and Batumi, they balked. They refused to accept the treaty and opted to go to war with the Ottomans, and then lost that war in less than a day.

What do you think was driving Ottomon policy in the South Caucasus following the October Revolution?

The Bolshevik seizure of power pleased the Ottomans for two reasons. One was that at a minimum it promised more turmoil for Russia, which for decades had posed the greatest and most direct threat to the Ottoman Empire. So any deepening of revolutionary chaos was good for the Ottomans in so far as it meant a weak and incapacitated Russia. The second was the hope that maybe, just maybe, the Bolsheviks were serious about their desire for a wholly new and different global order, one that was anti-imperialist. More specifically, the Bolsheviks’ call for a peace with no territorial annexations and no financial reparations suggested that the Ottomans should be able to obtain a restoration of the pre-war 1914 border with Russia and thereby recover the territories in Anatolia that they had lost during the war (e.g. Erzurum, Trabzon, Van etc.). There was also the hope among the Ottomans that perhaps they might be able to achieve the return of the provinces of Kars, Ardahan, and Batumi, all of which they had ceded to the Russian Empire in 1878 in lieu of financial reparations.

Beyond those questions of territorial re-acquisition, the Ottomans saw that with the formation of the Transcaucasian Commissariat there was the possibility of a buffer state against Russia emerging, and they saw this as immensely desirable. The prospect of putting geographical distance between their borders and those of Russia was highly attractive.

Not long into the negotiations at Brest-Litovsk the Ottomans became disillusioned with the Bolsheviks. The Bolsheviks’ interest in arming Armenian militias and using them to challenge the Ottomans convinced the Ottomans that a Bolshevik Russia would be little different from a tsarist Russia. At the same time, the Ottoman leadership (and their intelligence analysts) had no doubt that Russia, despite its current chaotic state, would recover and again pose a direct threat to the Ottoman Empire. Therefore, they concluded that they had a rare window of opportunity that they must exploit to establish a buffer state in the Caucasus.

Istanbul’s preference was for a single, unified Caucasus that would encompass the north and the south for three reasons. First, such a state would be bigger in terms of population and territory and thus a more effective buffer. Second, a unified Caucasus would neutralize or undercut Armenian claims to Anatolia by precluding the formation of a separate Armenian state and by enabling Georgians and Caucasian Muslims to keep Armenians in check. Third, as Enver Pasha argued, by including the Christian Georgians, a unified Caucasus would benefit the Muslims because the Georgians, with their higher “cultural level,” i.e. higher rates of literacy and education, would exert a positive influence on the Muslims (As Christians Georgians were afforded greater opportunities to attend schools and universities under the Russian Empire - Ed.).

Enver Pasha, the Ottoman Minister of War until October 1918, is the subject of a book which Dr Reynolds is currently working on. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Enver Pasha, the Ottoman Minister of War until October 1918, is the subject of a book which Dr Reynolds is currently working on. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

When, however, the Georgians precipitated the breakup of the Transcaucasian Federation by pulling out to declare their own independence, Istanbul quickly reacted by accepting and endorsing the establishment of an independent Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and North Caucasus. Aside from recovering the former Ottoman provinces of Kars, Ardahan, and Batumi, and the strip of land that ran alongside the Kars-Julfa railroad, the Ottomans had no territorial ambitions in the Caucasus and categorically rejected proposals for federation or union with Azerbaijan. The Ottoman leadership understood better than anyone else the relative weakness of their state and never entertained expansionist designs toward the Caucasus, Central Asia, or elsewhere.

To what extent do you feel the creation of the independent Transcaucasian republics, including the ADR, was a natural development of growing national sentiment or more of a reaction to imperial struggles in the Caucasus?

This is an excellent question. One of the central arguments of my book Shattering Empires is that the power of national sentiment has been vastly exaggerated. It is worthwhile to note, for example, that the Transcaucasian Commissariat was formed as a multi-ethnic entity and professed loyalty to a Russian democracy, not to nations. Moreover, even the very declarations of independence of the Georgian, Armenian, and Azerbaijani republics defy the conventional assumption that a rising groundswell of nationalisms constituted the main political forces of the period. They were not celebratory but even apologetic. The Bolsheviks had destroyed the promise of the February Revolution and of Russian democracy. This, together with the exigencies of the geopolitics of the moment, in the minds of the Transcaucasian elites, gave them little choice but to break from Russia and declare independence.

In Azerbaijan it is often said that it was the ADR that gave Yerevan, which had a large Muslim population, to the Armenians. What evidence have you found to support these claims?

The Georgians’ decision to follow a German invitation to declare Georgia a separate, sovereign country in exchange for German support and protection precipitated the break-up of the Transcaucasian Federation. It is worth noting that in the wake of the Georgians’ exit, it was not wholly evident to all that Azerbaijan and Armenia would also go their separate ways. However, when it did become clear that the Armenians preferred to go their own way, the Azerbaijani leadership decided not to contest the Armenians’ claim to Yerevan explicitly with the hope that this gesture of goodwill would be reciprocated.

Published Azerbaijani books discuss this, and I came across the correspondence on this in Azerbaijan’s archives. This is also confirmed in the Ottoman documentation from the era. Writing to the commander of the Ottoman Third Army, Vehib Pasha, on 27 May 1918 (i.e. the day before the Azerbaijanis and Armenians declared their independence), Enver Pasha explains that he had heard from Halil Pasha that the Muslims of the Caucasus are willing to compensate the Armenians for their losses in Anatolia with some of their own (the Muslims’) territory in the Caucasus. Enver then goes on to comment that this is a very dangerous idea, since an independent Armenia would be used by the British as a platform from which to challenge Ottoman control of Anatolia.

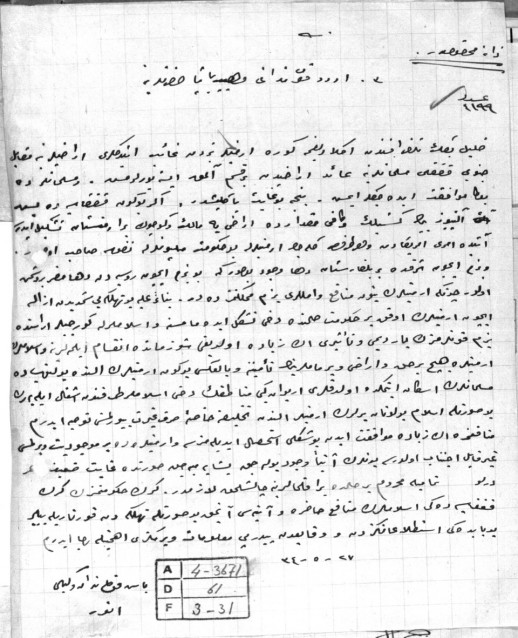

A letter written by Enver Pasha on 27 May 1918 to Vehib Pasha, commander of the Ottoman Third Army, expressing concern that the Muslims of the Caucasus might concede land to the Armenians. Photo: courtesy of Dr Michael Reynolds

A letter written by Enver Pasha on 27 May 1918 to Vehib Pasha, commander of the Ottoman Third Army, expressing concern that the Muslims of the Caucasus might concede land to the Armenians. Photo: courtesy of Dr Michael Reynolds

How should Azerbaijanis view this move today in the context of the ongoing Azerbaijan-Armenia conflict?

Given that this happened a century ago its relevance for today is quite limited. But Azerbaijan should perhaps make this fact better known in order to dispel the notion that the conflict with Armenia is driven simply by ethno-nationalist passion and to highlight the fact that Azerbaijanis have not been the age-old implacable enemies of Armenians, that they have been more than willing to compromise and indeed were willing to accommodate the Armenians at a time of the Armenians’ great desperation.

One consequence of the peace and friendship agreement signed between the ADR and the Ottoman Empire on 4 June 1918 was the formation of the Caucasus Army of Islam. Its name suggests a pan-Islamist movement, but in your opinion, what was its purpose and who formed its ranks?

The basic idea of the Caucasus Army of Islam was two-fold. The first was to act as what today we might call a “force multiplier.” The Ottomans in 1918 recognized that they had a rare strategic window or opportunity to put between their state and Russia one or more buffer states before the war came to an end and before Russia recovered its power. To do that, they needed to liberate Baku from the Bolsheviks, and thereby make the Azerbaijan Republic a viable state, and assist the North Caucasians in driving the Red Army out of Dagestan and the northeast Caucasus. But a major obstacle to carrying out these missions was that the Ottoman army had little manpower to spare for a campaign in the Caucasus, particularly as the British were in possession of Baghdad and were on the offensive in Mesopotamia and Palestine. Thus the Ottomans hit on the idea of using a skeleton force composed of officers who would recruit and train local Muslims. By employing the name “Caucasus Army of Islam” they could cite a common source of allegiance between the Ottomans, Azerbaijanis, and North Caucasians.

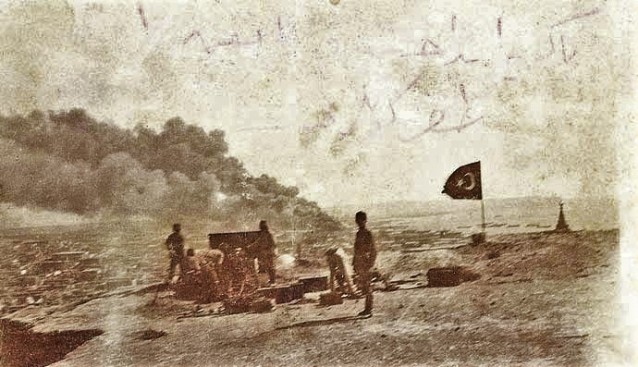

Azerbaijani and Turkish soldiers outside Baku prior to liberating the city in September 1918. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Azerbaijani and Turkish soldiers outside Baku prior to liberating the city in September 1918. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The second reason why the Ottomans called the expeditionary force the “Caucasus Army of Islam” was for the sake of maintaining a sort of deniability and to emphasize the grassroots support for the force, which was a powerful form of legitimacy in this new age of self-determination. Istanbul was aware that not only would the British and the Bolsheviks seek to block their efforts in the Caucasus, but that even their nominal ally the Germans would, too. The Germans nurtured the ambition to bring the Caucasus as a whole under their influence after the war to better exploit its resources and therefore they sought to limit Ottoman influence there. In the shorter term, they were desperate for oil from Baku and feared that the Ottomans, should they capture Baku, would not be capable of pumping and exporting the oil. In fact, the Germans did conclude a secret agreement with the Bolsheviks in which in return for oil they did what they could to disrupt and impede the advance of the Caucasus Army of Islam.

By calling it the “Army of Islam,” Istanbul was able to present a fiction of sorts to their ostensible German allies and to the Bolsheviks, with whom they were formally at peace, that the army was largely an indigenous force and not really under Ottoman control. It did not fool anyone but it did raise some confusion.

Despite its name, the Army of Islam had nothing to do with pan-Islam beyond drawing together the Ottomans, Azerbaijanis, and North Caucasians. It did not have as its mission an expanded Ottoman Empire or even the establishment of a Muslim state. Instead, its mission was to secure the independence of the Azerbaijan Republic and the Union of Allied Mountaineers in the North Caucasus. In fact, some ninety per cent of the officers of the indigenous component were not Muslims, but Christians. These were former tsarist officers who were opposed to the Bolsheviks and were unemployed and looking for a job. When asked by his superiors whether there were any problems with these non-Muslims, the commander of the Army of Islam, Nuri Pasha, responded that they were serving very well and that he was quite satisfied with them.

The front cover of Shattering Empires: The Clash and Collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires 1908-1918

The front cover of Shattering Empires: The Clash and Collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires 1908-1918

Assessing the ADR’s collapse in 1920, how important was the relationship between Bolshevik Russia and the Turkish liberation movement led by Mustafa Kemal?

Just as most historians have incorrectly portrayed the Ottoman intervention in the Caucasus as a hare-brained exercise in pan-Turkist or pan-Islamist expansionism, they mistakenly conclude that the intervention was a complete failure because the Mudros Armistice required the Ottomans to withdraw all of their personnel from the Caucasus. The fact is that the intervention achieved at least two important successes. The first is that the liberation of Baku in September made the Azerbaijan Republic viable. Although its independence lasted less than two years, this was enough of a precedent to ensure that the Soviets included Azerbaijan as a constituent republic, preserving the form of statehood if not the essence. The second is that the appearance of Ottoman influence in Azerbaijan and the Caucasus gave Mustafa Kemal leverage in dealing with Lenin. Mustafa Kemal was desperate for support against the British, French, Italians, Greeks, and Armenians. He was able to secure financial and arms support from Lenin in exchange for not contesting the Bolshevik conquest of the Caucasus. In a sense, the Turks’ success in their war of national salvation came at the expense of Azerbaijan. That being said, it is difficult to imagine that Mustafa Kemal, or any other potential outside actor with the exception of the British or perhaps the French, could have prevented the Red Army from conquering the Caucasus.

You mentioned that you are interested in writing a book about the ADR in the future – why is the ADR a topic that captures your interest?

The history of the first half of the twentieth century is, overall, quite a horrible one. This certainly applies to the story of the breakup of the Ottoman and Russian empires and World War I. The themes of violence, extremist politics, and inhumanity are the dominant ones. The story of the ADR, however, defies these themes. Although a short-lived entity, its emergence and brief life was remarkable. A parliamentary republic was born in a part of the world and a time in history where no one would have predicted it. This is a story that more people should know. It is, for example, quite stunning that in

the long running debates about the

compatibility of democracy and Islam or Muslim societies, the example of the ADR is very rarely cited.

Even the experts on these matters

are at best dimly aware of the ADR.

And many are completely ignorant.

The story of the ADR needs to be

weaved more prominently into the

histories of both the Middle East

and of Russia and Eurasia. I found

the founders of the ADR – men

such as Mammad Amin Rasulzade

and Ali Mardan Topchubashi –

quite intriguing. They were fundamentally decent and patriotic men

who in the midst of war and violent

revolution never lost their compass

and remained true to the their ideals

and to their country.