Pages 34-38

by Tamara Dragadze B.A. (Kent) D.Phil (Oxon)

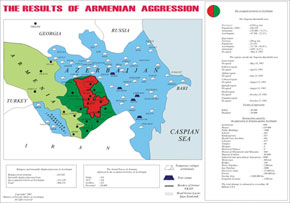

Unlike any other dispute in the former Soviet Union, the conflict in Nagorno Karabagh has affected and paralysed a whole region. For example, the South Caucasus as a whole is unable to attract the volume of investment necessary for development and marketing. The curse of the region, of the Caucasus both North and South, is that it is divided into such small units that to treat each one separately, according to local demand, is of no interest to serious developers because such small units are economically unviable.

All the advantages of regional cooperation, whether a customs union or shared defence costs or even a regional, quasi-federative assembly - akin to the European Union - are impossible because the Nagorno Karabagh conflict prevents all such movement between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Of course, Georgia too has local conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia but their being internal and peripheral means they do not have the same regional impact as the Nagorno Karabagh dispute. A strong South Caucasus would also be beneficial to the North Caucasus, economically, if not politically and culturally, even though the mini republics there are within the Russian Federation. But that kind of required strength is impossible without the coordinated efforts of all three South Caucasus republics. And to expect such coordination is unrealistic when two of the three republics are at war with each other.

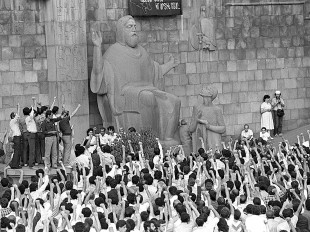

Conspiracy theories abound about why this tiny enclave of Mountainous Karabagh within Azerbaijan became the focus of such intense attention during the closing years of the Soviet Union. It is true that Gorbachev had little understanding of the nationalities questions of the USSR, indeed it was perhaps his main weakness, but we still do not know for certain whether or not there was a coordinated effort by the Security Services based in Moscow to ’divide and rule’ in the outlying republics where the first stir-rings of independence movements had begun. However much ethnic rhetoric was secretly encouraged or even provoked by the Central Government, it is regrettable that the peoples of the Caucasus were so willing to respond and follow. The blood letting in Georgia and Azerbaijan was matched only by the violent actions of the Soviet Army in Tbilisi and Baku. Ethnic cleansing on a massive scale in all three republics was the result, and it was left unpunished either when still under Soviet rule or after independence.

Throughout this short essay I will deliberately ignore the plethora of historical arguments, which insist that Karabagh is ’really’ Armenian, Caucasian Albanian, Azerbaijani or none! I do not believe that such arguments serve much purpose in the South Caucasus. In North America, the historical rights of aboriginal first nations to the land that was seized from them by droves of displaced Europeans and others, mainly in the last two centuries, do not provide a useful parallel for discussing the rights of ’original’ Karabaghis.

Although the rhetoric used by the protagonists in the Nagorno Karabagh dispute, Azerbaijani and Armenian alike, is ethnic, cultural and above all historical, the real dynamics of the conflict - and its resolution - have little to do with any of the above and much more to do with the big games of superpowers, such as Russia. So it is important to understand their reasons.

Not so long ago in the United States, I sat at dinner next to the former Russian envoy to Armenia and Azerbaijan, now long retired: Ambassador Kazimirov. I said to him that if I had been a Russian patriot, with Russia’s interests at heart, I would never want to let go of Nagorno Karabagh. Although he was unable to respond in words, his eyes said it all total agreement. And one cannot blame Russia or any other country from wanting to safeguard and promote its own national interests. In my opinion, after all, neither Georgia nor Azerbaijan have wanted the continuation of a Russian military presence on their soil and both are seeking a closer identity with NATO and the West, whereas Armenia allows not only its own foreign borders, but also those borders with Iran on the Azerbaijani territory under occupation, to be guarded by Russian guards. Should Georgia and Azerbaijan achieve their dream of European integration with all the material and other advantages that brings, how tempting that would be for Armenia too to forsake its former ally, but that remains impossible as long as the problem of Karabagh remains with the unavoidable necessity of having such close ties with Russia, its so far strongest and most loyal ally.

What is needed, therefore, is to find a situation or an argument so that Russia could find a greater advantage in helping to resolve the Karabagh problem than keeping it. A younger generation of Russians might come to believe that a more compact Russian Federation would be more governable and be more dynamic without the obligations of maintaining the remnants of an empire from former centuries - who knows? Or Iran and Turkey could also be brought into the same, more modest frame of mind, which would no doubt be encouraging to a new generation of Russians no longer needing to be obsessed with defending their southern borders. How great it is to dream! But it is not an impossible dream here.

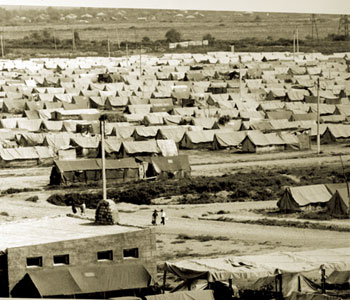

Another problem that needs solving, however, is that in Armenian politics the inter party rivalries, that even infant democracies thrive on, use rhetoric about Karabagh to defend their positions and work the crowds. Right from the start, it was the Karabagh issue which brought new politicians onto the streets in Soviet Armenia - Levon Ter-Petrossian included -and several doves who have made overtures towards peace have either lost their lives or their positions. Furthermore, the strong Armenian diaspora has entrenched views, some of them formed in the 19th century -Karabagh is a very old dispute - and it would take a great deal of persuading to change their views whilst allowing Armenia to hold on to their material and political support. Another problem lies in Azerbaijan itself. As long as there continues to be such a dramatic degree of inequality between the very rich and the poor, with the vast majority of Azerbaijanis as yet unable to enjoy the prosperity of a thriving, oil exporting state, there is little incentive for Nagorno Karabagh residents to look towards Baku when they receive alternative support from elsewhere. Can you imagine how different things would appear to them if, looking across the border, from the occupied lands into for example, Fizuli, they saw the returning refugees living in the luxurious opulence which an oil rich state’s inhabitants should enjoy! Naturally, in Karabagh there are some politicians and ordinary citizens who would put what they see as their national honour first - and in this case after so many years, it would be to continue to maintain the present status quo of Nagorno Karabagh - but many other citizens would be likely to put their children’s welfare first. I take it for granted that a fairer distribution of wealth is usually the result of a fair and democratic government where every citizen, regardless of race or creed, would feel they were ’stakeholders’. That kind of Azerbaijan might eventually have the same problems of controlling the enthusiastic influx of former citizens and immigrants as the United Kingdom struggles with today, and which Azerbaijan would undoubtedly solve more efficiently!

The above sounds a bit like a fairy tale, but dreams do come true sometimes, even in the Caucasus.

Unfortunately, one of the greatest casualties of the Karabagh conflict is that the new generation of Armenians and Azerbaijanis do not know each other. They are not neighbours, they are not fellow school mates, as they had been in Soviet times and under the Russian Tsars. Although there were massacres in both centuries, the vast majority of people did not live in conflict then, as witnessed by the numbers of people who intermarried. The few Armenians left in Azerbaijan today are mostly wives of Azerbaijani husbands and vice versa in Armenia, although there were some horrific stories of these cross marriages ending in tears at the height of the recent Karabagh war. Those Western organizations (I have called the ’peace industry’) which live by receiving funds for their conviction that they can solve conflicts through bringing private citizens from warring parties together for seminars and the like, certainly have an excellent role here, even if it is less exalted than many of them think. This is because nearly every time they have brought Azerbaijanis and Armenians together socially, they bond and get on really well. It is not on a large enough scale, and one can only hope that increased funding to these organizations will be forthcoming. What takes place even now is better than nothing and one must be very grateful for the opportunities these activities have created.

We can also be thankful for other ’small mercies’, as they say. It took tremendous tenacity by the Azerbaijani leadership for the line of the cease-fire to be where it is and not even further into Azerbaijani territory. I was once in Baku in the President’s Administration building, waiting to get presidential permission to interview someone I needed for my research, and at eleven o’clock at night the president’s foreign advisor emerged exhausted and pale. He explained that all day he and the president (Heydar Aliyev at that time) and their colleagues had sat without moving, without even being able to relieve themselves, because Ambassador Kazimirov had also sat there all day, also without even going to the toilet, hoping in this way to weaken their resolve. On the agenda was his proposal to have the front line and accompanying no man’s land 25 kilometres further into Azerbaijani territory than it is at present. But the old president, Heydar Aliyev, was as strong and stubborn as the conditions demanded and, of course, he won!

The cease-fire itself, let us not forget, was arranged by direct talks between Azerbaijan and Armenia, documents exchanged in Paris, with none of the intermediaries present and my hunch is that one day the final setting aside of hostilities and a just solution to the Karabagh situation will be achieved in the same way.

When I am asked what this just solution should be, I of course can see several ways out and they are all short term, whether it be a return to the situation before the war, respecting the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan and the relative autonomy of Nagorno Karabagh, or whether an exchange of territory would be more convenient (between the Lachin corridor and Zangelan to unite Nakhichevan with mainland Azerbaijan) but in all cases allowing for the secure return of refugees to their homelands.

In the longer term, of course, I would like to see the young generation of South Caucasians live in a region where all borders are progressively made weaker and more insignificant, where each republic contributes to the welfare of the other while retaining their uniqueness and their historical and cultural heritage.

by Tamara Dragadze B.A. (Kent) D.Phil (Oxon)

Unlike any other dispute in the former Soviet Union, the conflict in Nagorno Karabagh has affected and paralysed a whole region. For example, the South Caucasus as a whole is unable to attract the volume of investment necessary for development and marketing. The curse of the region, of the Caucasus both North and South, is that it is divided into such small units that to treat each one separately, according to local demand, is of no interest to serious developers because such small units are economically unviable.

All the advantages of regional cooperation, whether a customs union or shared defence costs or even a regional, quasi-federative assembly - akin to the European Union - are impossible because the Nagorno Karabagh conflict prevents all such movement between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Of course, Georgia too has local conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia but their being internal and peripheral means they do not have the same regional impact as the Nagorno Karabagh dispute. A strong South Caucasus would also be beneficial to the North Caucasus, economically, if not politically and culturally, even though the mini republics there are within the Russian Federation. But that kind of required strength is impossible without the coordinated efforts of all three South Caucasus republics. And to expect such coordination is unrealistic when two of the three republics are at war with each other.

Conspiracy theories abound about why this tiny enclave of Mountainous Karabagh within Azerbaijan became the focus of such intense attention during the closing years of the Soviet Union. It is true that Gorbachev had little understanding of the nationalities questions of the USSR, indeed it was perhaps his main weakness, but we still do not know for certain whether or not there was a coordinated effort by the Security Services based in Moscow to ’divide and rule’ in the outlying republics where the first stir-rings of independence movements had begun. However much ethnic rhetoric was secretly encouraged or even provoked by the Central Government, it is regrettable that the peoples of the Caucasus were so willing to respond and follow. The blood letting in Georgia and Azerbaijan was matched only by the violent actions of the Soviet Army in Tbilisi and Baku. Ethnic cleansing on a massive scale in all three republics was the result, and it was left unpunished either when still under Soviet rule or after independence.

Throughout this short essay I will deliberately ignore the plethora of historical arguments, which insist that Karabagh is ’really’ Armenian, Caucasian Albanian, Azerbaijani or none! I do not believe that such arguments serve much purpose in the South Caucasus. In North America, the historical rights of aboriginal first nations to the land that was seized from them by droves of displaced Europeans and others, mainly in the last two centuries, do not provide a useful parallel for discussing the rights of ’original’ Karabaghis.

Although the rhetoric used by the protagonists in the Nagorno Karabagh dispute, Azerbaijani and Armenian alike, is ethnic, cultural and above all historical, the real dynamics of the conflict - and its resolution - have little to do with any of the above and much more to do with the big games of superpowers, such as Russia. So it is important to understand their reasons.

Not so long ago in the United States, I sat at dinner next to the former Russian envoy to Armenia and Azerbaijan, now long retired: Ambassador Kazimirov. I said to him that if I had been a Russian patriot, with Russia’s interests at heart, I would never want to let go of Nagorno Karabagh. Although he was unable to respond in words, his eyes said it all total agreement. And one cannot blame Russia or any other country from wanting to safeguard and promote its own national interests. In my opinion, after all, neither Georgia nor Azerbaijan have wanted the continuation of a Russian military presence on their soil and both are seeking a closer identity with NATO and the West, whereas Armenia allows not only its own foreign borders, but also those borders with Iran on the Azerbaijani territory under occupation, to be guarded by Russian guards. Should Georgia and Azerbaijan achieve their dream of European integration with all the material and other advantages that brings, how tempting that would be for Armenia too to forsake its former ally, but that remains impossible as long as the problem of Karabagh remains with the unavoidable necessity of having such close ties with Russia, its so far strongest and most loyal ally.

What is needed, therefore, is to find a situation or an argument so that Russia could find a greater advantage in helping to resolve the Karabagh problem than keeping it. A younger generation of Russians might come to believe that a more compact Russian Federation would be more governable and be more dynamic without the obligations of maintaining the remnants of an empire from former centuries - who knows? Or Iran and Turkey could also be brought into the same, more modest frame of mind, which would no doubt be encouraging to a new generation of Russians no longer needing to be obsessed with defending their southern borders. How great it is to dream! But it is not an impossible dream here.

Another problem that needs solving, however, is that in Armenian politics the inter party rivalries, that even infant democracies thrive on, use rhetoric about Karabagh to defend their positions and work the crowds. Right from the start, it was the Karabagh issue which brought new politicians onto the streets in Soviet Armenia - Levon Ter-Petrossian included -and several doves who have made overtures towards peace have either lost their lives or their positions. Furthermore, the strong Armenian diaspora has entrenched views, some of them formed in the 19th century -Karabagh is a very old dispute - and it would take a great deal of persuading to change their views whilst allowing Armenia to hold on to their material and political support. Another problem lies in Azerbaijan itself. As long as there continues to be such a dramatic degree of inequality between the very rich and the poor, with the vast majority of Azerbaijanis as yet unable to enjoy the prosperity of a thriving, oil exporting state, there is little incentive for Nagorno Karabagh residents to look towards Baku when they receive alternative support from elsewhere. Can you imagine how different things would appear to them if, looking across the border, from the occupied lands into for example, Fizuli, they saw the returning refugees living in the luxurious opulence which an oil rich state’s inhabitants should enjoy! Naturally, in Karabagh there are some politicians and ordinary citizens who would put what they see as their national honour first - and in this case after so many years, it would be to continue to maintain the present status quo of Nagorno Karabagh - but many other citizens would be likely to put their children’s welfare first. I take it for granted that a fairer distribution of wealth is usually the result of a fair and democratic government where every citizen, regardless of race or creed, would feel they were ’stakeholders’. That kind of Azerbaijan might eventually have the same problems of controlling the enthusiastic influx of former citizens and immigrants as the United Kingdom struggles with today, and which Azerbaijan would undoubtedly solve more efficiently!

The above sounds a bit like a fairy tale, but dreams do come true sometimes, even in the Caucasus.

Unfortunately, one of the greatest casualties of the Karabagh conflict is that the new generation of Armenians and Azerbaijanis do not know each other. They are not neighbours, they are not fellow school mates, as they had been in Soviet times and under the Russian Tsars. Although there were massacres in both centuries, the vast majority of people did not live in conflict then, as witnessed by the numbers of people who intermarried. The few Armenians left in Azerbaijan today are mostly wives of Azerbaijani husbands and vice versa in Armenia, although there were some horrific stories of these cross marriages ending in tears at the height of the recent Karabagh war. Those Western organizations (I have called the ’peace industry’) which live by receiving funds for their conviction that they can solve conflicts through bringing private citizens from warring parties together for seminars and the like, certainly have an excellent role here, even if it is less exalted than many of them think. This is because nearly every time they have brought Azerbaijanis and Armenians together socially, they bond and get on really well. It is not on a large enough scale, and one can only hope that increased funding to these organizations will be forthcoming. What takes place even now is better than nothing and one must be very grateful for the opportunities these activities have created.

We can also be thankful for other ’small mercies’, as they say. It took tremendous tenacity by the Azerbaijani leadership for the line of the cease-fire to be where it is and not even further into Azerbaijani territory. I was once in Baku in the President’s Administration building, waiting to get presidential permission to interview someone I needed for my research, and at eleven o’clock at night the president’s foreign advisor emerged exhausted and pale. He explained that all day he and the president (Heydar Aliyev at that time) and their colleagues had sat without moving, without even being able to relieve themselves, because Ambassador Kazimirov had also sat there all day, also without even going to the toilet, hoping in this way to weaken their resolve. On the agenda was his proposal to have the front line and accompanying no man’s land 25 kilometres further into Azerbaijani territory than it is at present. But the old president, Heydar Aliyev, was as strong and stubborn as the conditions demanded and, of course, he won!

The cease-fire itself, let us not forget, was arranged by direct talks between Azerbaijan and Armenia, documents exchanged in Paris, with none of the intermediaries present and my hunch is that one day the final setting aside of hostilities and a just solution to the Karabagh situation will be achieved in the same way.

When I am asked what this just solution should be, I of course can see several ways out and they are all short term, whether it be a return to the situation before the war, respecting the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan and the relative autonomy of Nagorno Karabagh, or whether an exchange of territory would be more convenient (between the Lachin corridor and Zangelan to unite Nakhichevan with mainland Azerbaijan) but in all cases allowing for the secure return of refugees to their homelands.

In the longer term, of course, I would like to see the young generation of South Caucasians live in a region where all borders are progressively made weaker and more insignificant, where each republic contributes to the welfare of the other while retaining their uniqueness and their historical and cultural heritage.