Martha Lawry, an American who lived in Azerbaijan for eight years, learned to play the saz and found herself within a community of national musicians. The following is her memoir of her experiences as a foreigner inside the Azerbaijani ashug world.

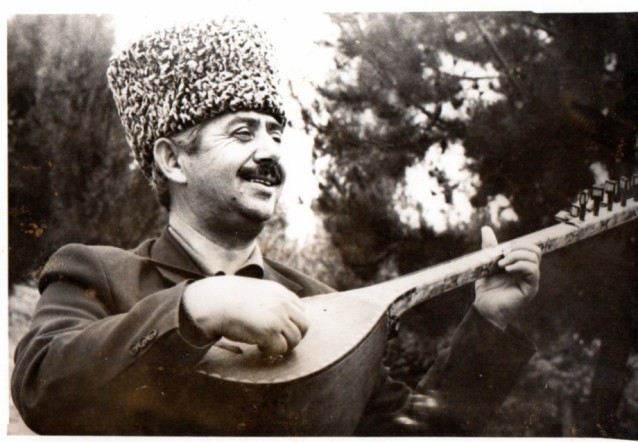

The first time I played on national TV, there was no studio audience, just an array of cameras staring blankly at me. The room was eerily quiet as my saz teacher’s daughter and I began to strum our instruments. I was desperately trying not to pay attention to the red lights on top of the cameras, the monitor screen in front of me which alternated between closeups of my face and my partner’s, or the fly that kept circling in front of my face as we played. Honoured Artist Samira Aliyeva. Photo: courtesy of the Azerbaijan Ashug Community

Honoured Artist Samira Aliyeva. Photo: courtesy of the Azerbaijan Ashug Community

That was back when I was too proud, or responsible, to write the song lyrics on my instrument on a sticky note. I had been diligently practising, and I was relying on my memory to get through the song, which almost took more concentration than I could muster. I was wearing borrowed national dress that dragged across the floor as I walked.

I thought that performance would be a one-time deal, but when the Azerbaijani public saw a full-blooded American playing their national instrument and crooning in a village accent, they were intrigued enough to turn a blind eye to my mistakes and invite me to play for them again and again

An untouched frontier

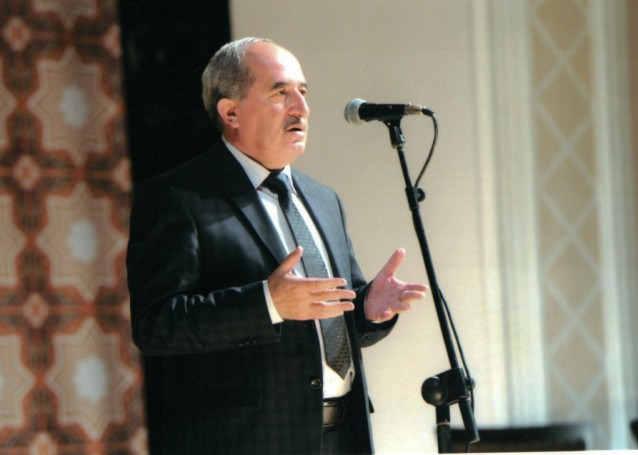

Several years later I found myself at the front of an auditorium full of Technical University students. This performance was unexpected for me, and I was told in the middle of the concert that I would be playing two numbers, not one as I had prepared. Somehow I got through a second song, but not without forgetting the lyrics several times. Maharram Gasimli, something of a curator of folklore and saz music who had invited me to perform, scolded me after the concert. You have to stop looking at the audience, he said. You’re distracting yourself.

He was right, but I couldn’t help it. There’s a sort of manic state that comes over me when I’m on stage. I feel a wave of love for the people watching me, a deep desire to connect with them through their music. The rhythm and the energy carry my hands, and my eyes search the crowd for eye contact, familiar faces, or smiles of knowing acceptance.

Older people especially relate to ashug music because it is so traditional. This is an untouched frontier of Azerbaijani culture where there is very little integration of anything foreign. Ashug songs are meant to be sung in village accents. The saz isn’t the instrument of the educated or the elite; this is the old folk instrument that village farming families have in their back room somewhere collecting dust. Ashug music is closely tied to the Azerbaijani language, and it resists translation because of its high dependence on rhyme and syllable structure, as well as poetic features like plays on words that only work in this language.

One semester, I took an Ashug Literature class at Khazar University as part of my master’s programme. There I was introduced to the principles of ashug poetry. There is an accepted canon of tunes that ashugs play (the favourites in the repertoire vary by geographic region, but most saz players agree that there is a total of somewhere between 70 and 80 tunes that are specifically performed on saz). These tunes are written with a certain number of syllables to a line, but each tune can be sung with any poem that fits the structure of the music.

In Azerbaijani literature, there are many fixed structures of poems. For example, English literature has the sonnet and the limerick, which are both strict forms with a certain number of syllables per line and set rhyme schemes. Azerbaijani literature has the qoshma (an 11-syllable line), the gerayli (a seven-syllable line), and other forms. An ashug tune written for a qoshma can be sung with any qoshma, giving the performer a great range of freedom to choose the content of the song.

Sounds of the saz

Because the ashug world is so embedded in Azerbaijani village culture, people would often come up to me after concerts asking how on earth I, an American, ended up here, playing this music.

When I moved in with an Azerbaijani family in 2010, I soon realised that my personal catharsis sessions on guitar weren’t familiar enough to be pleasing to their ears. When I played and sang, they would go in the other room and turn up the volume on the TV. I found myself longing to play music I could share with people around me. It was a form of loneliness I had never experienced before. I needed to share the experience of music with someone who would enjoy it along with me, either as an observer or as a participant.

Honoured Artist Isfendiyar Rustamov. Photo: courtesy of the Azer- baijan Ashug Community

Honoured Artist Isfendiyar Rustamov. Photo: courtesy of the Azer- baijan Ashug Community

One day Islam, my little brother in my local host family, took an instrument down from its perch atop a cabinet and dusted it off. It was a saz: a long-necked, lute-like wooden instrument with strings doubled or tripled up on three pitches. He started to strum out a rhythm across the strings, which make a simple chord when they’re all played together. Then he began to pick out a melody on the highest pitched set of strings.

The saz has almost a metallic ringing sound because of its large resonance chamber. Unlike a guitar, it has three pinholes under the strings where the sound escapes. As Islam played a more complex tune, I couldn’t help but run to my room to dig out my mp3 recorder so I could capture some of the exotic sound.

The family explained to me that saz is usually used to accompany oneself singing. This was the local equivalent to my unwanted guitar. It wasn’t long before I was looking for a teacher so I could take up saz myself.

My first few lessons were frustrating. I was used to learning from sheet music, but ashug music is almost entirely orally passed down. My teacher would play a few bars of a song and then I was expected to repeat them over and over until I remembered them. It was challenging for me to remember the unfamiliar music, especially because many saz tunes are repetitive and the song builds on a few riffs that are repeated periodically as the song progresses. I had a hard time keeping the “road map” of the music in mind as I played.

The ashug world isn’t just a body of musical knowledge, it is a subculture and a tight-knit community

I also learned that teacher-student relationships are not just about passing on knowledge and honing skills like the music lessons of my Western childhood had been; they are more like an apprenticeship where the student is expected to be loyal and the teacher passes along ethical principles, guidelines for leading a party, poetry knowledge, and even his or her own personal connections. The ashug world isn’t just a body of musical knowledge, it is a subculture and a tight-knit community

Head of the Azerbaijan Ashug Community Maharram Qasimli. Photo: courtesy of the Azerbaijan Ashug Community

Head of the Azerbaijan Ashug Community Maharram Qasimli. Photo: courtesy of the Azerbaijan Ashug Community

The ashug subculture

When I discovered the ashug community, my musical longings were fulfilled. Ashug music is fairly audience participatory. The traditional role of the ashug is an entertainer for parties; he or she feels the vibe of the room and matches it, helping the people present to express their emotions or celebrate together. People often make song requests. When an ashug plays at a home gathering, people can shout out “yasha!” (“live long!”) or “sag ol” (thank you) to spur him on. In some regions, people clap along or dance. It is expected that the audience express their appreciation for the music.

The best kind of performance was at weddings, because I would stand in the front and centre of the room and inevitably someone would have to hold a microphone for me. The cameraman would come over and get right in my face, and two or three stray children would gather at my feet. Once a little girl, captivated by the dance rhythm of the music, took my skirt in both hands and began to wave it up and down until she was dragged away by a modesty-minded parent.

The acoustics were never quite right, and there was always a microphone feedback squeal or a glitch as they tried to get the microphone positioned so people could actually hear my voice. Then the background musicians liked to pitch in with percussion or synthesizer chords (sometimes even in the right key). I finally learned how to look back at them and give cues, and we could pass the melody back and forth. That didn’t happen successfully until I had suffered a handful of botched accompaniments, because there was never a practice session in advance.

Sometimes a few people would start to dance. I always felt like such a part of the community, surrounded by musicians and audience on all sides.

Ashug music is very regulated by syllable, so stock phrases are used to fill empty syllables at the end of a line when the music calls for more than the lyrics provide. In Azerbaijani there is a saying that When the ashug runs out of words, he says “agrin alim...” That phrase, which is used as a term of endearment, literally means Let me take your pain.

And through the years in Azerbaijan, ashug music really did take away my pain by giving me a way to express emotions so that people around me could understand them on a heart level. From the overflow of the music, the ashug expresses his affection – sometimes for a beloved referred to in the song, or to the audience, or for the music itself. Some of the songs are lyrical and they express longing, for an estranged lover, or for the distant mountains, for example. I too have found comfort in the lines of sad songs as I’ve processed transition and loss. One song in particular never fails to get a reaction out of my Gedebey friends: If I die in a foreign land, the land and the sky will cry for me.

Another song says: Maybe I will never come back here again... take care, rain; take care, mountains. As I move away from Azerbaijan this year, I do fully hope to come back and sing with these friends again. But until then, take care, Azerbaijan.

About the author: Martha Coffman is a former staff writer at Visions and an expert on Azerbaijani music and culture.