If I were to sum up what Baku means to me then it would be the internal connection that unites everyone, says Ilkin Yagubov, a photographer whose soulful black-and-white images explore his native city and the villages of the Absheron peninsula.

Out there otherworldly landscapes harbour ancient traditions and have attracted generations of local artists, writers and photographers: My childhood spent on the Absheron influenced my perception of the world and left a distinct imprint. I identify myself with the Absheron and everything that’s connected with it, he says.

Equipped with an old Hasselblad or Leica and rolls of grainy film, Ilkin drifts between the ancient rock formations of Qobustan, Baku’s bazaars and the beaches of the Caspian, capturing scenes blending fine art and documentary.

With every year I delve deeper into fine art photography. Over the years the way I see things and my photography have changed a lot. The way I see myself in photography has changed. Photography has become a way of life. I’ve moved away from commercial photography and decided to concentrate on fine art.

Baku’s tumblers

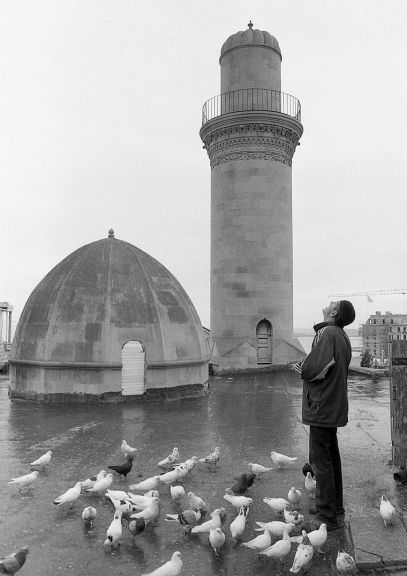

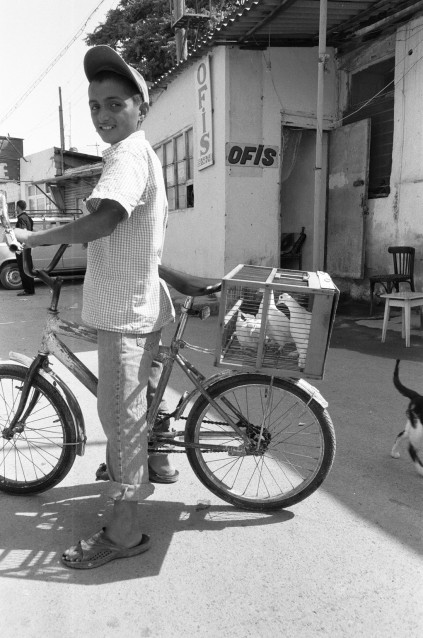

Seven years ago, however, when Ilkin was closer to the social documentary end of the spectrum he began a project that resonates with that ‘‘internal connection’’ he mentions above. The subjects of this series of atmospheric photographs, which he continues to shoot from time to time, are the city’s once thriving community of pigeon keepers.

Pigeons have been kept domestically for millennia and for a multitude of reasons – for exhibiting, eating, racing and as recently as World War II they were famously used to send messages. Many fanciers (as they’re also known) simply find harmony in the company of the birds and this is also true of Baku’s pigeon keepers. Until recently pigeon keeping was a popular pastime in the Azerbaijani capital and its nearby villages. There’s even an iconic local breed of pigeon called the Baku Tumbler which is renowned for its flying abilities. Typically soaring so high as to disappear from sight, it remains in the air for up to eight hours, from time to time clicking its wings and performing acrobatic rolls.

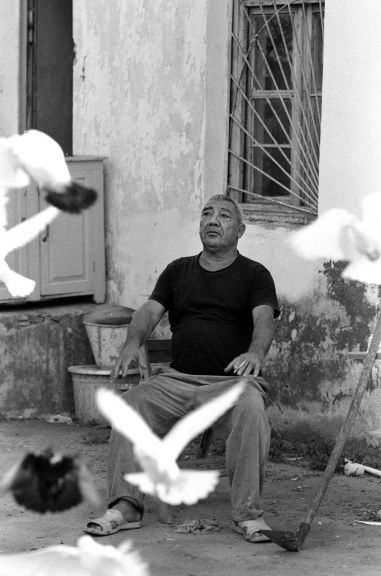

I remember very well the time when every morning you could see hundreds of pigeons fluttering in the sky, and their owners sitting, usually, on the rooves of one and two-storey houses and chasing them with long sticks, recalls Ilkin.

And there can’t have been any houses in Baku’s villages where pigeons weren’t kept. And even when moving each summer to the dacha they would take the pigeons with them. In the morning, in the rays of the rising sun, you could see fluttering birds and hear the sounds of flapping wings in the suburban stillness.

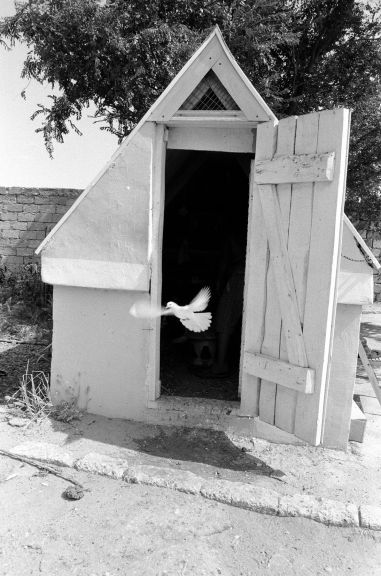

One obvious reason for the gradual disappearance of this subculture from central parts of the city is the quickly changing urban environment. Many of those old one- and two-storey houses in areas like Sovetski, for example, have been replaced by modern apartment blocks. Another factor is economic, as feeding, housing and guarding pigeons has become increasingly costly and onerous.

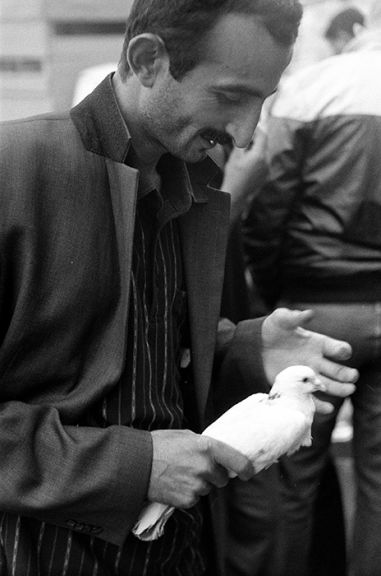

For some, though, breeding pigeons is actually a business and a single bird can fetch anything between just a few manats and several hundred: Cases where pigeons are exchanged for cars are very common. There are pigeon lofts with alarms and even with guards, Ilkin says. Indeed, one experienced fancier I met while researching this article guards his lofts with three ferocious Shamakhi sheepdogs. They’ll eat anyone that comes in, he said, and I don’t believe he was joking.

Those not in it for the money have differing motivations: I’m sure that if you were to ask a pigeon fancier why he keeps pigeons it would be impossible to get an intelligible answer, says Ilkin, adding that in many cases it’s as simple as continuing a family tradition.

Ilkin studied photography under Sanan Aleskerov, a pioneer of contemporary Azerbaijani photography who Visions interviewed last year (see "Life Through the Lens of Sanan Aleskerov" in the summer 2017 issue) and it was during a lesson exploring the work of American photographer Ralph Gibson, whose minimalism strongly influenced Ilkin, that he pencilled in his notebook – Start shooting pigeon keepers. In terms of bringing the idea to fruition, he says:

My close friend is from a family of pigeon fanciers and it was with him that I began to take pictures, and thanks to him I was able to get close to the quite closed community of pigeon fanciers. We began by explaining to the fanciers why I was doing this and showing them pictures I’d already taken and many agreed to be photographed. With some of them I became good friends and continue to occasionally photograph them. The most difficult thing was to get to the market where all the pigeon fanciers gather once a week from all the surrounding villages. After some time people began to recognise me at this market and now they sometimes invite me to photograph them with the pigeons.

The city’s underbelly

Digging beyond Baku’s chic, 21st-century facade, the series takes us deep into the city’s underbelly – from bustling pigeon bazaars to the gritty backyards of Absheron villages and the cramped rooves of the Old (Inner) City where oppressive urban scenery juxtaposes with the pigeons’ soft white plumes. And it’s this uncanny proximity to nature that goes to the heart of what it means to keep them:

In my opinion pigeon fanciers identify themselves with the birds they raise, with their beauty, grace and physical strength and most importantly with their love for freedom. The moment they see the pigeons flying they’re also on top of the world. I even began to notice in myself that when I watch pigeons flying I feel a sense of freedom, a light euphoria, Ilkin says.

Indeed, look closely and you might just see this sense of “light euphoria’’ frozen on the faces of Ilkin’s subjects – a human aspect absent from much of his more recent work. Today he is more drawn to unpeopled landscapes, yet continues to push the boundaries of black-and-white and express an attachment to his native land. Unlike many photographers enticed by the bright lights of exotic locations abroad, Azerbaijan still provides Ilkin with plenty of inspiration:

There are lots of places on the Absheron and in Azerbaijan which I want to visit. I’ve already begun one project on the Absheron but there’s still a lot to do. And throughout Azerbaijan there are many places that I’d like to go to; to my shame I’ll say that I’ve still never been to Nakhchivan. I really want to go there.

And if he does he would do well to follow his own advice. Probing him for any wisdom he might share with foreign photographers wishing to capture the essence of Azerbaijan, he says: Let the place go through you, feel it. I think that when you do, the photographs will have a deeper meaning.

To see more of Baku and the Absheron from a local perspective, follow Ilkin on Instagram at @ilkinyagubov and visit his website at www.ilkinyagubov.com