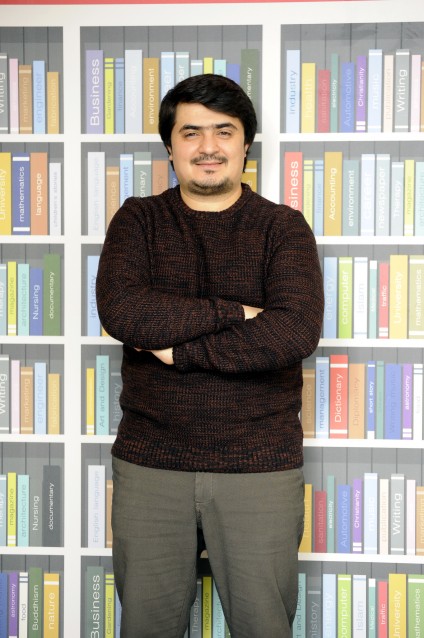

In 2015 Visions published an interview with Azerbaijani collector and author Dilgam Ahmad. The interview was a general overview of his collection and what motivates him, but given that his interests centre on early 20th-century Azerbaijan, the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (referred to mainly throughout this article as the Republic of Azerbaijan) and Azerbaijani emigration, we decided to get back in touch with Dilgam for the final article in our series marking the centenary of the ADR.

VoA – Why are you especially interested in these areas of Azerbaijani history?

DA – The Republic of Azerbaijan, founded on 28 May 1918, is one of the greatest contributions of Azerbaijani Turks to the history of mankind. The Azerbaijani Turks established a national state for the first time, set up a multi-party parliament and formed a government with religious, class, social, national and gender equality. The history of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the political emigration from Azerbaijan, which is its continuation, is a value and an ideal for me. I study their heritage, meet with family members, collect archival material and search for graves.

Can you tell us about your collection and the unique items it contains?

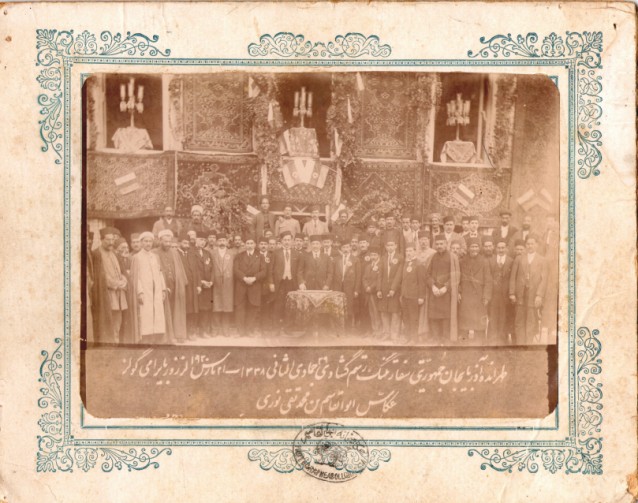

My collection is mainly related to the Republic of Azerbaijan and the history of emigration. The material belonging to the republican period is the following: the first coat of arms of the Republic of Azerbaijan; a photo of the editorial staff of the newspaper Azərbaycan (Azerbaijan – Ed.), the official state newspaper of the republic (1919); a photo from the opening of the republic’s embassy in Tehran (March 1920); a photo of events to mark the first anniversary of the republic (28 May 1919); a photo of our delegation headed by Mammad Amin Rasulzade at the Istanbul conference together with Ottoman representatives (June 1918); photos of political figures like Alimardan Topchubashov and Ahmad Hamdi Garaagazade (a former member of parliament of the ADR and correspondent of the newspaper Azərbaycan – Ed.).

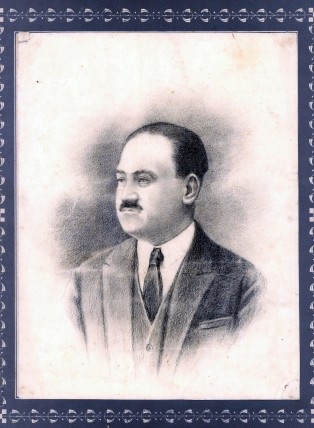

My emigration archive is richer. For example, [there is] a rare photo of Rasulzade taken in Hyvinkaa in Finland in 1922, photos related to the 9th and 10th anniversaries of the republic in Istanbul, an album of 34 photos from Rasulzade’s funeral, and there are dozens of photos and letters of Miryagub Mirmehdiyev, Abbasgulu Kazimzade, Mirzabala Mahammadzade, Almas Ildirim, Ahmad Aghaoghlu, Mustafa Vakiloglu and others.

Which do you feel are the most valuable items and which are your personal favourites?

The most valuable things for me are photographs and letters belonging to the founder of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Mammad Amin Rasulzade. I have two photos of Rasulzade alone and five photos of him with his associates. In addition, I have three postcards sent by Rasulzade about his state of health from Poland to his friends in Istanbul in 1932. These are very valuable to me. The other things I love are two paintings. One of them is the first coat of arms of our republic, and the other is a painting that I call Self-Portrait of an Independence Supporter, which we used for the cover of our book From One to a Hundred Years.

How have you built this collection?

I‘ve acquired 90 per cent of the material from Istanbul, Turkey. As you know, after Azerbaijan was occupied by Russia in 1920, Azerbaijani politicians, writers and poets were forced to emigrate. Istanbul was the city where most of them gathered and lived. The family members of some émigrés handed over their archives to Turkish state universities and some to museums in Azerbaijan. Unfortunately, some of the archives were destroyed after their death and some were included in various private collections. Some fell into the hands of booksellers called sahaf in Turkey. I’ve been buying material relating to the Republic of Azerbaijan and the history of emigration from an old bookseller I met in Istanbul four years ago.

I must say that Azerbaijani citizens and our compatriots living abroad have given me financial support to buy these things. I collected some funds through campaigns on social networks and thanks to this I was able to buy them. On the other hand, family members of émigrés have given me valuable items. For example, Tektas Aghaoghlu, the grandson of the renowned public and political figure in Azerbaijan and Turkey Ahmad Aghaoghlu, gave me some unique items about his grandfather and father. Among them was Ahmad Aghaoghlu’s diary, which he wrote while in exile on the island of Malta, photos he took on the island and his letters to his family.

Besides photos and documents, are there any other interesting items?

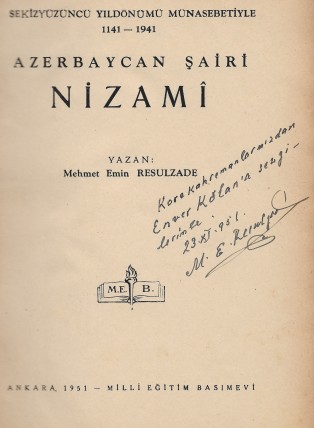

I have a very rich collection of books and magazines. I’ve collected almost 90 per cent of the magazines and books published in emigration. For example, I have copies of magazines like Yeni Kafkasya, Azeri Turk, Odlu Yurd, Azərbaycan Yurd Bilgisi, Gurtulush, Ergenekon Yolu and Turk Izi, more than 250 copies of the newspaper Azərbaycan and a complete collection of the magazines Mujahid and Turk Yolu. I also have a book entitled The Azerbaijani Poet Nizami signed by Rasulzade himself. Rasulzade signed this book for an Azerbaijani who participated in the Korean War in 1951.

I’m also insterested in collecting signed books. For example, I have copies of the books Memories of Azerbaijan’s Fight for Independence and Sympathy by Nagi Sheykhzamanli, head of the Republic of Azerbaijan’s organization for fighting counterrevolution; Mirzabala Mahammadzadeh’s National Azerbaijan Movement; Ergenekon Roads and Iranian Turks by Mahammadsadig Aran, a member of the republic’s parliament; Fallen Idols by Shafi Rustambayli, another member of parliament; Kerim Oder’s The Azerbaijani Economy;

Ahmad Aghaoghlu’s

Britain and India;

Huseyn Baykar’s The

History of Azerbaijan’s

Fight for Independence

and Renewal Movements

in Azerbaijan; and Almas Ildirim’s Bayatis.

I have some very rare books ranging from Rasulzade’s books in Arabic script to those published in emigration until 1990. My book collection also includes books in Latin script published in Azerbaijan from 1922 to 1939. I have nearly a hundred books.

We know you like collecting things about Uzeyir Hajibeyov – why does he interest you in particular? Are there any other figures you are especially trying to document?

We know Uzeyir Hajibeyov as a composer, the author of the anthem of the Republic of Azerbaijan and valuable operas. But I would say that he is one of the greatest publicists in the history of Azerbaijan. Specifically, his political articles in the newspaper Azərbaycan are so interesting and so deep in terms of coverage that while reading these articles we see a huge personality before us. Uzeyir Hajibeyov’s articles also shed light on the history of our republic. That’s why I’m trying to collect materials related to Uzeyir Hajibeyov.

The rarest item I have relating to Uzeyir Hajibeyov is a book published in 1908. This book, entitled Arithmetic Exercises, was published by Gulamrza Sharifzade and Abbasgulu Kazimzade in the Orujov brothers’ printing house in 1908. This work attracted Mammad Amin Rasulzade’s attention and he wrote an article about it in the 91st edition of the newspaper Taraggi on 2 November 1908. I’ve also bought brochures of Uzeyir Hajibeyov’s shows staged in Ankara and Istanbul. The most valuable one is a brochure of a performance of If Not That One, Then This One by the Azerbaijan Youth Association. The brochure notes that we shouldn’t forget that Azerbaijan, which is currently held captive, is a Turkic land.

As for other personalities, there are archival documents of the republic’s statesmen who weren’t living in exile. For example, I have original photographs belonging to the member of parliament and educator Sultan Majid Ganizade and the minister of railways and telegraph, Khudadat Malikaslanov.

In an interview with Visions in 2015 you described your collecting as a historical responsibility rather than a hobby. Why do you think this?

I stick to my opinion, because every item I find is part of the history of Azerbaijan, and it doesn’t have a second copy. One letter can have only one copy, while a photograph has five copies at best. The photos and letters of Rasulzade I’ve acquired have created a new source for studying his political and personal life. I mostly buy items that I can use in my books and that will benefit researchers. If I don’t buy them, another Turkish citizen will buy them and maybe they will never become known to the Azerbaijani public. I constantly visit booksellers in Istanbul, follow auctions, and try to buy material about us. For example, in October, I bought a document about a student who came to Turkey at the time, and I also bought the academic report of an Azerbaijani who studied in Russia. These will also be included in my next book. Therefore, the work I’m doing entails more responsibility.

What interesting things have you learnt about the ADR by collecting all this material?

For example, the photograph on the front page of my book Return of the Émigrés was very important for the republic’s history. We knew about this conference in Istanbul, but the photo of the representatives of Azerbaijan and the Ottoman Empire together wasn’t known. It’s probably the first photo taken with representatives of the Ottoman Empire, with which we established our first diplomatic relations. Also, reading the texts of the letters I’ve bought, I’ve been able to examine the relationships between our émigrés and to see what challenges they faced. There are photographs that have caused important historical events to be discovered.

As an Azerbaijani collector and historian, what do you feel is the significance of the ADR for the country today?

Our book The Republic of Azerbaijan: A Brief Historical Essay, which I wrote together with Professor Adalat Tahirzade, will soon be published. We noted in the book that all the activities of the republic’s government were aimed at showing a people that had been oppressed for over 100 years a new democratic way of life. In fact, this was a revolutionary process from a historical point of view. It wasn’t so easy to instill self-government in a people

ruled by monarchs for

thousands of years.

However, the successes

of the Azerbaijani parliament in a short period

of time proved that the

Azerbaijani people were

ready for and capable of

democratic reforms. The parliament successfully ruled the country from December 1918 until the end of April 1920. Taking into consideration that most of this period saw interventions by Turkish and Entente armed forces in Azerbaijan, we can be sure about the difficult situation that the parliament and the government overcame.

The Republic of Azerbaijan was the first modern state in the Muslim East to be named after a geographical territory, it was the first republic, the first parliamentary state, the first multi-party, democratic and law-governed state (in the Muslim East – Ed.), the first secular state, the first national state, the first state that had a general election law and officially recognized women’s rights to elect and be elected many years before most European states. It was the first state to officially recognize women’s right to work in the same positions as men, the first state to officially declare the religious, sectarian, class, social, national and sexual equality of all its citizens. All this is an indication of the kind of values we had.

What do you plan to do with your collection in the future?

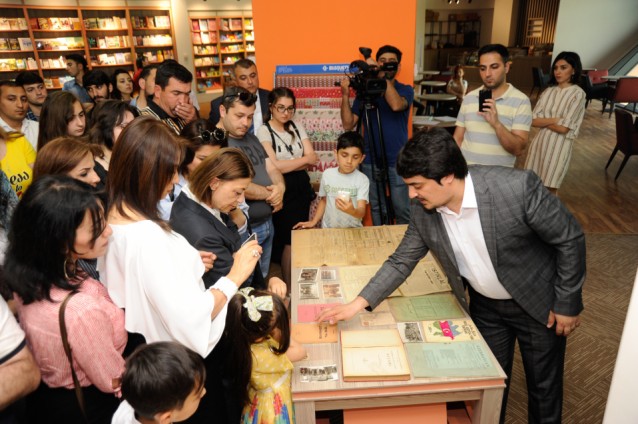

My biggest wish is to create an Azerbaijani Emigration House. I think this centre should consist of two parts. One part will be a museum, which will include the materials I’ve collected.

The other will be a library used by researchers and students. I want everyone to benefit from the material I have acquired and people to visit the museum to see the historical items up close. I’ve held 23 exhibitions in different universities, schools and organizations during the Year of the Republic (2018 – Ed.). I saw the interest people showed. So I want all the material to be gathered in one centre. I would gladly accept the support of the Azerbaijani state and businessmen in this regard.