As 2019 has been declared the Year of Nasimi in Azerbaijan, the following article explores the great poet’s life, work and ideas.

A decade ago, on my second trip to Baku, I stumbled across a little faded green volume of Azerbaijani poetry excerpts, translated into English. Countless times I had passed under the regal statues of the beloved poets of Azerbaijan silently observing Fountains Square from their balcony post in the Azerbaijani Literature Museum, but I had not yet taken the time to read the works of the poets that Azerbaijanis revere and memorize from their childhood.

I couldn’t put it down. Even in a translation, which can never fully render the melody and intricacies of the verses in their original language, the words nudged my core.

A poet of neighbouring Persia, Hafiz, once wrote, A poet is someone who can pour light into a cup, then raise it to nourish your beautiful, parched, holy mouth.

Indeed, the ancient poets of Azerbaijan continue to nourish their posterity with timeless and universal truth, keen insight, and furling passion.

A pursuer of divine truth

Imadaddin Nasimi stands out with a delightful relevance in this cohort. A mystic poet who wrote during the turn of the 14th century, Nasimi’s poetry filters religious dogma and dispenses a delicate sherbet of truth and empathy. His verses navigate the search for understanding, union with the Divine, and love for humanity. Nasimi’s work probes the depths of imago dei, a risky undertaking in his day. The poet was not unaware of the perils of his philosophy; he frequently evokes the Persian poet Hallaj Mansur, who had been famously put to death decades earlier for declaring, I am the Truth:

Take the noose, burn brightly – you who, like Mansur, say: “I am God!”

You in other worlds will gain a haven safe from any foe!

While many saw Mansur’s declaration as blatant heresy, others understood the mystic to be declaring that the essence of God existed within humanity. Nasimi’s own mentor and tutor, Fazlullah Astarabadi, was likewise condemned and executed for charges of heresy in Nakhchivan.

Tragically, Nasimi eventually met a similar fate, and the legend of his death highlights the themes of his life. Nasimi had left Baku for Turkey in 1394, he was eventually imprisoned for spreading the Hurufi philosophy of Fazlullah. One day, one of his disciples was seized while reciting a ghazal of Nasimi’s:

To see my face you need an eye that can perceive True God. How can the eye that is short-sighted see the face of God?

The authorities demanded that the young man identify the origin of the verses, but he bravely claimed the poetry as his own to avoid implicating Nasimi. However, upon becoming aware of the incident, Nasimi immediately revealed himself as the ghazal’s creator and was consequently sentenced to death by flaying, effectively giving up his own life in sacrifice for another.

The pull of the mystical

Nasimi’s controversial themes were typical of the mystics of the region, most of whom adhered to Sufi Islam or offshoots of it. Interestingly, in recent years, the poetry of ancient Persian mystics has enjoyed a surge of popularity in the United States and Europe. Indeed, many writers have sought to answer the question, how did the ancient Persian mystic Rumi become one of the best-selling poets of the United States? Nasimi, writing in Persian, Arabic, and Azerbaijani Turkish, lifted Turkic literature to the calibre of the Persian and Arabic divans, or collections.

Nasimi’s mentor Fazlullah was himself inspired by Rumi. Fazlullah had been born into a family of judges and began the profession at an early age when his father passed away. However, his life path was irrevocably altered when one day, upon hearing a nomadic dervish reciting verses of Rumi, the young Fazlullah entered a powerful trance. When he asked his own religious instructor to reveal the meaning of the words, the man answered that one could only understand the meaning by devoting oneself to a lifetime of spiritual devotion and thereby experiencing the answer rather than intellectually learning it.

Fazlullah attempted to maintain his work as a judge during the day by retreating to a cemetery at night to pray in solitude, but eventually he set aside his work entirely and gave up a life of comfort and possessions to pursue spiritual understanding. His pursuits birthed the doctrine of Hurufism, one of the core beliefs of which was that God has made himself manifest in the word and in the face of man. The word huruf means letters in Arabic, and Hurufism allocated significant importance to the esoteric meaning and numeric values of letters.

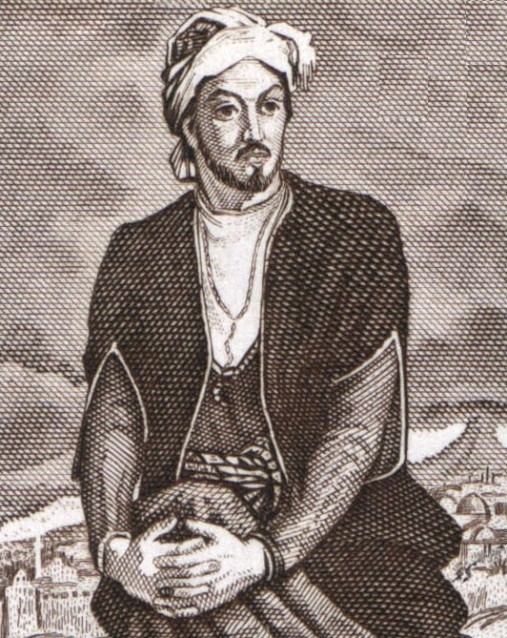

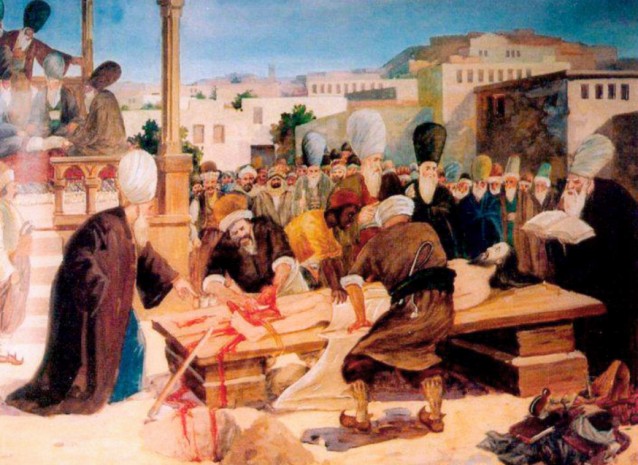

From a film called Nasimi, produced by the Azerbaijanfilm studio in 1973 for the 600th anniversary of the poet’s birth. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

From a film called Nasimi, produced by the Azerbaijanfilm studio in 1973 for the 600th anniversary of the poet’s birth. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Meeting Place of the Human and the Divine

Nasimi became a devoted follower of Fazlullah, and the themes of Hurufism permeate his poetry. Nasimi centres his work on exploring the nuances of human nature:

If you’re not a devil, know and study man,

Speak of Adam’s essence, origin and sway!

He frequently explores the mystery of man being made in the image of God:

Know God, acknowledge him, Nasimi! You are mankind’s son

And I am he who did receive from God the name of man.

Both worlds within my compass come, but this world cannot compass me

An omnipresent pearl am I and both worlds cannot compass me.

Because in me both earth and heaven and Creation’s “BE!” were found,

Be silent! For there is no commentary that can encompass me.

The Hurufi significance assigned to letters and their numerical values is ubiquitous in his work:

Supreme God is himself humanity’s son

Of God’s words thirty-two letters are the sum.

The whole of the world is the All-Holy One.

And man – a soul whose countenance is the sun.

And...

It’s from God that I come with tiding of glee

I beheld there an “L” and “O”, “V” and “E”

And in all eighteen thousand words did I see

The Divinity: all-pervading is he.

The poet exalts the pursuit of love over pretension and positions of power:

Who would be like Mansur seeks neither pulpit nor throne.

Into the noose of love sublime his neck he shall thrust.

And deconstructs the brick wall dividing sacred and secular:

Do you not say that God is everywhere?

Why do you then distinguish between the tavern and the mosque?

He sets forth a philosophy of peacebuilding and nonviolence:

Accept this truth: I harm no one and hurt for hurt I’ll not exchange.

And...

I have no share in the enslavement of man. God knows I speak the truth.

He champions the foundational concept of human rights, that every human has intrinsic value:

O you who call a stone and earth a precious pearl, is not man who is so fair and gentle also a pearl?

The Intimate Connection Between Creation and Creator

In typical Sufi form, Nasimi’s spiritual themes are embodied in the tender imagery of a lover yearning for his beloved. In Sufi poetry, human eros frequently symbolizes the intimate union between God and humans that Sufis believe is the ideal state. But Nasimi’s verses also stand on their own as delightful love poetry, glimpsing the complex passion and yearning of lovers.

The whole world is surrendering to your grace.

You brought God’s secret forth from its hiding place.

Without you what is soul, or loving the world?

It’s you who is soul and the lover’s world embrace.

Your lips are the source of life. But, God be praised,

Not everyone to your lips the source can trace.

Who drinks life-giving water? Ask of the man

Who once the wine of your ruby lips did taste.

In the tradition of the mystics, Nasimi’s poetry is a splendid divan of universal truth and beauty. His ideas reach down into the core of humankind and stretch across the globe in their relevance and effect. In an era that is increasingly divisive, Nasimi’s truths are like a balm delivered by tender and empathetic hands.

A living legacy

In celebration of Nasimi’s work, last autumn in Azerbaijan, artists, musicians, writers, and thinkers of all varieties gathered in a four-day festival to explore the themes of Nasimi and their significance to our world today. The Nasimi Festival of Poetry, Arts, and Spirituality sought to intertwine ancient ideas of spirituality with modern notions, rooted in the timeless and universal concepts of Nasimi. The festival featured a range of diverse collaboration and artistic expression, including visual arts exhibitions, a fair-trade and ethical fashion design, inclusive community dance, immersive theatre production, and outdoor poetry installations across the Old City.

The coordinator of the festival, Mr Jahangir Selimkhanov, is a cultural policy and arts management expert, with an extensive history in developing and preserving the intangible cultural heritage of Azerbaijan and collaborating with cultural organizations and individuals across the globe. I asked Mr Selimkhanov to elaborate on the goals and outcomes of the festival.

VoA: What core concepts of Nasimi’s poetry and ideas did the festival celebrate?

JS: The main strands for building up the concept of the Nasimi Festival were developed by Ms Leyla Aliyeva, the Vice President of the Heydar Aliyev Foundation – to pay tribute to the unique personality of Imadeddin Nasimi and, in the meantime, to reach out far beyond a bio-festival by celebrating spirituality, which was the main characteristic of the great poet’s worldview. The festival is meant to attract, and ideally unify, very diverse audiences, and the following perspectives diverge in concentric, scaling circles: the personality of Nasimi and the interpretation of his many-valued poetic heritage; the ideas of“tasawwuf”and“hurufiyya,” reflected in Nasimi’s poetry (spiritual growth and perfection, the light of knowledge of truth, emanation of the divine in man, the esoteric meaning of script and letter); and “pantheism” (in a very loose interpretation of this scholarly term) and inter-confessional embrace, the universal scale of the spirit of Nasimi; and modern views on spirituality – at the junction of diverse traditional denominations, or outside the orthodox religious doctrines, which through the centuries echoes with the spiritual aspirations of Nasimi.

The festival’s motto is Beyond the limited self, supported by a quote from Nasimi’s famous verse: I’m a particle, I’m the sun (Zərrə mənəm, günəş mənəm). The key concepts of the festival included quest for truth, altruism/compassionate love, spiritual intelligence, and empathy.

Thematic vectors included balance with nature, creativity, strength of the human spirit, self-overcoming, and striving for light and virtue.

VoA: describe your impressions of the Bahariyya Music Project of the festival, which you directed. (You can view the performance at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gozhKHmMVeU).

JS: It was indeed an unforgettable event – the performance took place in an old industrial heritage building, the very first power station of Baku, which is now home to the Stone Chronicle Museum, with its solemnly impressive stone walls, 10-metre-long windows, and fabulous acoustic ambience. The bold yet meaningful light design by Dutch light artist Andre Pronk and stage outfits by Orkhan Gadim added to the mystery of extraordinary revelation.

VoA: What would you say was the over-all impact of the festival on participants?

JS: Throughout the festival we received very positive feedback. It was quite a risk to include a lecture on shared economy in the 21st century, or the performance of the Recycled Orchestra from Paraguay featuring teenagers playing on musical instruments made of scraps from a landfill, or the exhibition of Brian Eno’s work with computer-manipulated “generative” images and sound content and so on – and all that in a festival named after a poet who lived more than six centuries ago! However, in each case the message was clearly articulated in connection to Nasimi’s spiritual pathos and aspirations.

This is in contrast with, for example, the intellectually provocative “gesture” of Peter Sellars, who designed an entire cultural festival dedicated to the jubilee of Mozart without performing a single note from his massive oeuvre (see https://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/25/theater/25sell.html). We tried to balance between paving the way to a better understanding and appreciation of the complex language of Nasimi’s poetics while simultaneously imagining him as our contemporary.

VoA: What wider impact do you believe an event like the Nasimi Festival can have on the country as a whole?

JS: It would be too ambitious to pretend that a single cultural event could produce any measurable impact on the whole country. We simply did our best to present an example of an event that is open (if not boundless) in terms of cultural domains and art disciplines represented, striving for artistic excellence, and, in the meantime, inclusive and participatory questions rather than assertions. As Gert Naessens, Operations and Project Manager of the European Festival Association, stated in a letter sent upon completion of the Festival,

Even in the first edition, it’s clear that the festival has a high potential and is on its way to becoming an example for the region. Con-gratulations for organizing such a great festival within this very short period of time!

The festival, organized by the Heydar Aliyev Foundation, is set to become an annual event. In one of his quatrains, Nasimi once lamented,

Where shall one find a true friend of pure heart?

Where is the man of conscience and justice?

Certainly the poet would have been gratified to the depth of his being to know that the ideals he lived and died for have been resurrected centuries later in this dynamic annual gathering to collaboratively influence a deeper understanding in society of spirituality, truth, justice, artistic expression, and human love.

About the author: Tia Hasanova is a writer from the United States. She writes content and curriculum for US companies, focused on language acquisition and cross-cultural communication.