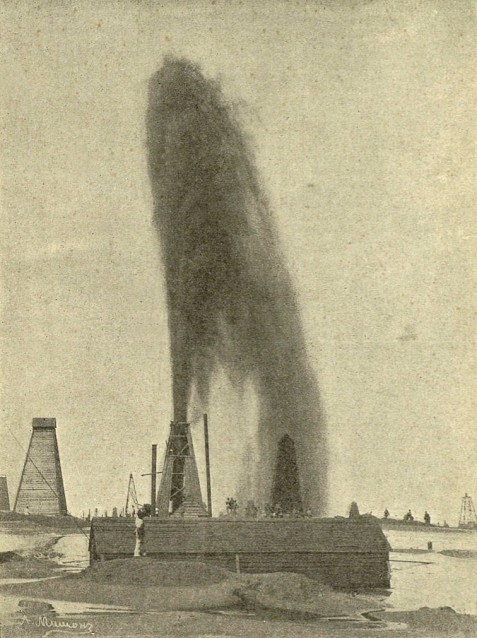

To mark the 140th anniversary of Branobel, the oil company founded by the Nobel brothers, and the 115th anniversary of the establishment of the Baku Prize named after Emanuel Nobel, oil historian Mir-Yusif Mir-Babayev explores how before the First World War the Nobels’ company became the undisputed leader of the Russian (and hence Baku) oil industry at international exhibitions.

For many years in the pre-revolutionary period (until 1917) Branobel was the undisputed leader of the Russian oil business (whose main oil-producing region was Baku – Ed.) and as a frequent participant of international exhibitions it played a significant role in its promotion abroad.

The Nobel brothers began their activity on the Absheron peninsula in 1875. On 18 May 1879 the Nobels’ company, Branobel, was officially formed with capital of three million roubles. In 1884 this company began to participate successfully at many international exhibitions, illustrating its achievements in the oil business in London (1884), Antwerp (1885 and 1894), Paris (1889 and 1900), Chicago (1893), Stockholm (1897), Glasgow (1901) and Turin (1911).

On 8 May 1884 the International Health Exhibition was opened in London. The organizing committee was headed by Albert Victor, Prince of Wales (son of the future British King Edward VII). The London exhibition presented a variety of exhibits from the leading countries of Europe and North America. For the quality of its oil products shown, the Nobels’ company received a medal, which served as an important incentive and gave the company’s management, headed by Ludvig Nobel, confidence in the correctness of their chosen path – the European oil and kerosene market.

The next exhibition in which the Nobels took part was the World’s Fair in Antwerp, Belgium, which opened on 2 May 1885. By 1884, Branobel had produced 15.2 million poods of oil (1 pood equalling roughly 16.4 kg – Ed.) and developed about 9.7 million poods of kerosene. But its main achievement was considered organising the production of lubricating oils in Russia: 740 thousand poods of petroleum distillates had already been extracted, which could also be exported. The jury of the exhibition in Belgium appreciated the quality and range of products from the Russian oil industry; the highest award – Honorary Diplomas (Grand Prixs) – were given for the Nobels’ kerosene and mineral oils, as well as for the mineral lubricating oils produced by the Victor Ragozin Partnership. The mineral lubricants of the Sidor Shibaev Partnership were awarded a gold medal and a silver medal was won by the Baku company of Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev, one of the oldest Russian oil trading companies – established in 1872 – which in 1885 produced seven million poods of oil and two million poods of kerosene.

Success at the Belgian exhibition confirmed that Ludvig Nobel was on the right path by developing the company’s exports. In terms of how Branobel arranged its sales of oil products, the outstanding chemist Dmitri Mendeleev commented: With respect to trade, and especially to the transport of petroleum products, mainly through the efforts of the largest companies of the Nobel brothers and those imitating them, it has been done to perfection, surpassing everything that has been done in other countries.

Paris, Chicago, Antwerp and Stockholm

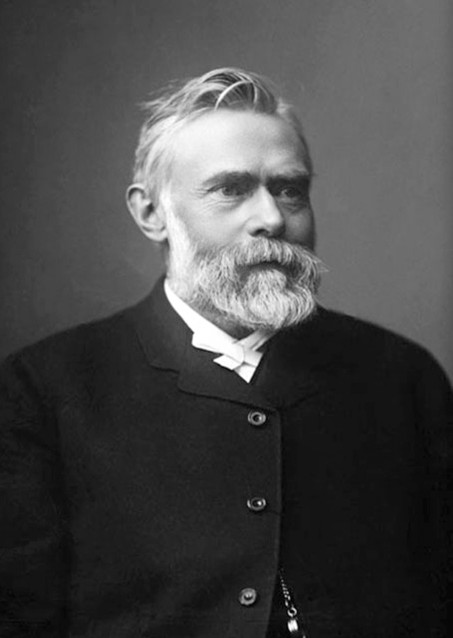

At the Exposition Universelle in Paris on 5 May 1889 Branobel – now led by Emanuel Nobel (1859-1932) after Ludvig Nobel’s death in 1888 (Ludvig left control of the company to his son, Emanuel) – was strongly represented as the year of the exhibition coincided with the tenth anniversary of the company. The main symbol of the Parisian exhibition was the 317-metre steel tower designed by engineer Gustave Eiffel (1832-1923), which was twice as high as the Pyramid of Cheops. The international jury praised the high-quality products of the Nobels’ company, awarding it the highest award – the Grand Prix – in two categories: mining and metallurgy, and chemical and pharmaceutical products. It is worth noting that in 1889 the annual production of oil by the various companies operating in the Baku oil fields amounted to 207 million poods, and on the world market Russian oil products became a serious competitor to American kerosene and lubricating oils. This was undoubtedly largely thanks to the Nobels’ company.

1 May 1893 in Chicago saw the grand opening of the World’s Columbian Exhibition (also known as the Chicago World’s Fair) to mark the 400th anniversary of the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus. It was attended by US President Grover Cleveland (1837-1908) and 45 countries from across Europe, Asia and the Americas, while 37 colonies and 24 US states were also represented there. In all, 70 thousand participants displayed some 250 thousand exhibits. Emanuel Nobel had decided to take part in this North American exhibition to make the most of the opportunity to learn about the experience of its main competitor on a global scale – the American company Standard Oil founded by John D. Rockefeller. But for both Ludvig Nobel and his son Emanuel, John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) was not only a rival and competitor on the global market, but also a business guide.

The Branobel exhibit earned high praise at the Chicago exhibition. It included a brochure summarizing its activities, samples of crude oil and its products following fractional distillation, as well as asphalt, sulfuric acid and caustic soda, and photo albums of its factories, fields, steamers and filling stations. Head of the company Emanuel Nobel was awarded twice, and one of the company’s mining engineers, Michael Belyamin (1863-1926), was also awarded for the organisation and design of the Nobel’s display.

On 5 May 1894 the World Exhibition reopened in Antwerp, the city where Branobel had won its first Grand Prix in 1885. For this exhibition the company arrived with its best ever results: in 1893 the company’s share capital amounted to 15 million roubles; in fields (mainly in Baku) it had produced 24.4 million poods of oil, which accounted for 7.5 per cent of the entire volume of oil production in Russia (in 1893 the total amount of oil produced by the different companies in the Baku oil fields reached 344.7 million poods). 18.5 million poods of kerosene had been produced, of which 12.1 million was used in Russia, and the rest was exported abroad. At this exhibition in Belgium the Nobels’ company again received the highest award, the Grand Prix, for the quality of its oil products.

The next international exhibition attended by the Nobels took place in the homeland of their ancestors, in Stockholm, Sweden, opening on 15 May 1897 in the presence of Swedish King Oscar II (1829-1907). Invitations were sent by the organizing committee of the Stockholm exhibition to representatives of the Swedish diaspora worldwide. Emanuel Nobel made a firm decision to participate in the exhibition at the highest level, in memory of the company’s principal founders who had passed away. The newspaper New Era wrote the following about the exhibition: Opening in Stockholm, the exhibition will once again present an opportunity for a fraternal meeting of peoples and a reason for many thousands of people to learn about Scandinavia, this northern country, the homeland of the ancient Skalds. Naturally, the Swedish Exhibition Organizing Committee awarded Branobel the highest award – a gold medal – for its unique display.

A photochrom print of the Stockholm World's Fair, 1897. Photo: Detroit Publishing Co./Wikimedia Commons

A photochrom print of the Stockholm World's Fair, 1897. Photo: Detroit Publishing Co./Wikimedia Commons

Turn of the century

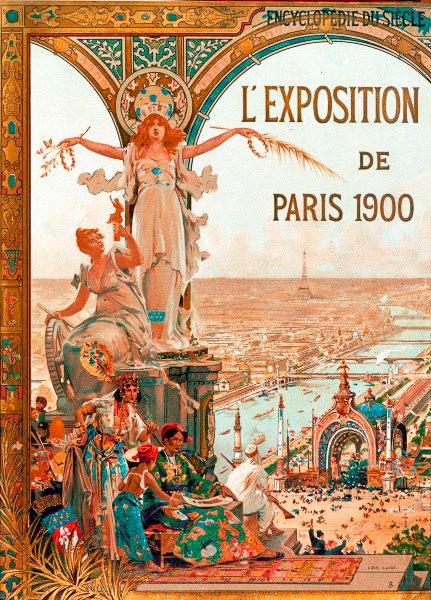

The 19th century ended with the Exposition Universelle in Paris, which summed up the scientific results of the century and set new boundaries for progressive scientific thought. The official opening ceremony happened on 14 April 1900 and was attended by French President Francois Emile Lube (1838-1929), members of the government and the national parliament, as well as representatives of the business world and scientific and creative intelligentsia. Branobel exhibited an extensive range of Russian oil products and refinery equipment; it was shown how in 1899 the company’s fields, encompassing 340 wells, produced just under 95 million poods of oil. The company’s annual revenues totalled more than two million roubles. Once again, following a decision by the international jury, Branobel and the Rothschild’s Caspian-Black Sea Oil Industry and Trade Society (founded in 1883 by the brothers Alphonse and Edmond Rothschild) received the top honour, the Grand Prix, for their exhibits.

The winner of the gold medal at the Paris exhibition was one of the oldest and leading Russian oil companies, the Baku Oil Society, founded in 1874 and the world’s first vertically integrated joint-stock company. It was founded by Peter Kokorev and Vasily Gubonin based on an oil refinery in Surakhani.

On 1 May 1901 the grand opening of the International Exhibition took place in Glasgow, Scotland, at which members of the royal family (Princess Louise Dagmar and her husband the Duke of Fife) were present on behalf of the British monarch, accompanied by officials and Scottish lords. As at previous exhibitions, Branobel’s exhibit was at the centre of oil specialists’ attention: in 1900, the company had produced 86.9 million poods of oil from 113 production wells and 30.1 million poods of kerosene. In the same year, the company had sent 15 million 753 thousand poods of kerosene abroad, which was over 25 per cent of the total exports of kerosene. In Glasgow too Branobel was awarded the Honorary Diploma by an international jury.

It should be noted here that of the oil produced in the period 1899-1901 the Russian oil industry ranked first in the world, giving 11.5 million tonnes of oil per year, whereas the United States was producing 9.1 million tonnes per year. In the year of the Glasgow exhibition Russia produced 55 per cent of the world’s oil, and the Baku oil region accounted for 95 per cent of the empire’s oil production. Oil extraction by the various companies operating in the Baku oil fields amounted to 671.6 million poods per year. The growth of the oil industry in Baku at the end of the 19th century meant Russia became the world’s leading oil-producing country; since 1901 Russia long maintained second place (after the USA) before later being overtaken by Mexico.

Turin international

On 29 April 1911 the official opening of the World’s Fair in Turin, called the Turin International, was held in the main pavilion in Valentino Park in this northern Italian city. Italy had won the right to host the World Exhibition for the first time in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the kingdom of Italy, which had been proclaimed by the country’s first parliament in February 1861. The ceremony was attended by Italian King Victor Emanuel III (1869-1947) and his wife, while the exhibition showcased exhibits from 31 states.

Emanuel Nobel decided to participate in this exhibition as he considered it an important step to further expanding his presence in the Mediterranean oil market. Up to then, the Nobel company’s success in the Russian oil business had been stunning, so it was no surprise that Branobel’s informative exposition was firmly in the public eye. It included many pictures, diagrams and charts illustrating the different priority areas of the company’s activity. Visitors learned that in 1910, oil production in the Nobels’ oil fields was 63.6 million poods, meaning Branobel’s share in all-Russian oil production had reached 11 per cent. 9.6 million poods of kerosene were exported; the company’s share in total Russian kerosene exports accounted for 31.4 per cent. Foreign consumers received 2.7 million poods of lubricating oils and 1.4 million poods of fuel oil.

A special exhibit by Branobel showed samples of various petroleum products: gasoline, kerosene, a wide range of lubricants for various uses in transport and industry. A novelty at the exhibition was a new product, Tunisian kerosene, designed for hot countries with a flash point of 32-33 oС. A large section of the Turin exhibition was dedicated to the Nobel’s fleet. Over the previous 32 years, the company had done enormous work in this area, starting with the world’s first tanker Zoroaster, which had been carrying out a regular service across the Caspian Sea since 1878. Several new ships and barges had been built almost every year. In total, the Nobels’ oil transport fleet consisted of 14 marine tankers, 43 river ships and 209 oil barges. Naturally, the international jury in Turin praised these tremendous achievements and Branobel received two Grand Prixs – one for trade navigation by sea, river and lake and the other for the extractive and chemical industry category. And the director of the Baku branch of the company and its fleet, Carl Wilhelm Hagelin (1860-1954), personally received a certificate of excellence.

The Italian exhibition was to be the last foreign exhibition in which the Nobels’ company participated. Like all those before it, this exhibition showed the enthusiasm, efficiency and diligence with which the company’s management went about achieving great results.

The efficiency and effectiveness of the Nobels’ company at international exhibitions meant that for many years until the First World War it was the undisputed leader of the Russian oil industry in the exhibition business. In the context of today, applying some of the rich organizational and technological experience of this successful company would undoubtedly be extremely useful, necessary even, for the current generation of Azerbaijani oilmen.

Incidentally, on 15 October 2018, to mark the 185th anniversary of his birth, a monument was unveiled to Alfred Nobel, the founder of the International Nobel Prize at Villa Petrolia (the Nobel brothers’ former residence in Baku – Ed.). The opening was addressed by the vice chairman of the Nobel Family Society, the great-nephew of Emanuel Nobel, Professor Thomas Tüden.

About the author: Mir-Yusif Mir-Babayev is a doctor of chemistry, a professor at the Azerbaijan Technical University and author of books on Azerbaijan’s oil history. Discover much more of his work at www.visions.az.