In 1881, following the assassination of reformist tsar Alexander II, a wave of anti-Jewish pogroms swept across the Russian Empire. His successor, Alexander III, issued a series of anti-Semitic laws in May of 1882 which effectively undid all of the liberal achievements of the former ruler. As a result of these events, the Hovevei Zion movement (meaning “Those Loving Zion”) appeared in Jewish settlements across the western regions of the empire and had the goal of recreating the Jewish state.

Then, a few years later in 1895, events in France served to further strengthen the Zionist cause. A Jewish officer in the French Army by the name of Alfred Dreyfus was taken to trial (and charged with espionage and treason – false charges that were later discovered to have resulted from the anti-Semitic views of his superiors, and it was years before he was finally released from prison, pardoned, and reinstated in the army – Ed.). Following this, a strong wave of anti-Semitism engulfed France, and as Austrian Jewish journalist Theodor Herzl wrote, Jews felt the need to unite in the face of a common threat. In 1896, he published a book called The Jewish State, in which he proclaimed the need to return the Jews to their historical homeland.

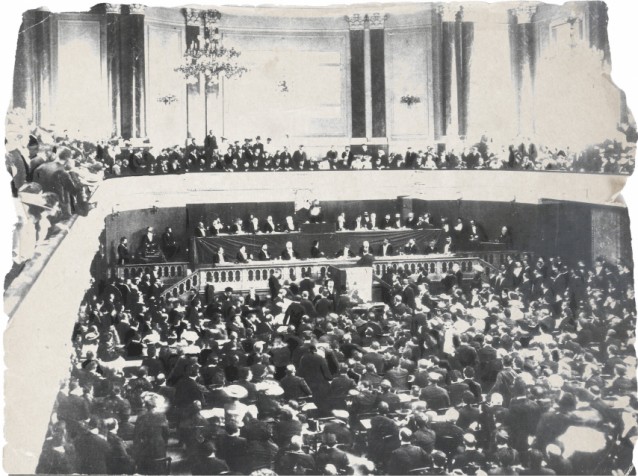

The following year, Jews held a congress in Basel, Switzerland, which resulted in the formation of the Zionist Organization. It systematically oversaw the process of resettling Eastern European Jews to Palestine, then a province of the Ottoman Empire.

Baku Zionists

Baku had already become one of the major centres of Jewish nationalism with the appearance of a branch of Hovevei Zion in 1891. In 1899, a Zionist organization was set up there by E. Kaplan, and in 1902, four representatives of Azerbaijan’s Jewish community attended the second All-Russian Zionist Conference in Minsk. The following year, Baku Zionist E. Eysenbet attended the sixth World Zionist Congress in Basel. This period saw the steady growth of Azerbaijan’s Zionist movement, whose activeness is reflected in notices such as the following published in the newspaper Kaspi:

On Sunday 18 May 1908 a general meeting of the Pal-estine Society will be held at the synagogue, where S. M. Aleynikov will read a report about the most recent cultural and economic innovations in Palestine. Starts at 6pm.

Judging by publications in the press, Baku’s Zionists felt no need to hide despite the local police monitoring their activities very closely; archival records from 1912 show the latter proposing the government monitor and suppress the increasing “criminal” activity of the Marxist-Zionist party Poale Zion. The fact that the Zionist movement was a completely new phenomenon for the Russian Empire’s security services is evidenced by this secret report by the head of the Baku Secret Police Department from 23 May 1911, in which it is referred to as an ordinary political party:

According to information received, in the middle of November last year a conference of the Bazel central committee of the Zionists party took place which decreed to gather a congress of all the parties affiliated with Zion-ism this summer in the city of Bazel, Switzerland.

Nevertheless, Zionists in Baku openly cooperated with those from other provinces of the empire. With the permission of the local authorities, they held various events, the proceeds of which went towards supporting farming settlements in Palestine. For example, one letter, sent from the Odessa-based Committee for Assistance to Jewish Farmers and Artisans in Syria and Palestine in February 1911, granted Jews in Azerbaijan permission to arrange a meeting in the city of Baku with the proper permission of the local authorities in favour of the society and send the proceeds, minus expenses, to the Committee.

The Zionist movement in Azerbaijan was particularly active in 1918-1920 under the independent Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, in which the Jewish community was represented in the parliament of the republic by the chairman of the Jewish National Council, a Zionist named M. A. Gukhman. The newspaper Azerbaijan carried regular articles about the activities of the Zionists, ranging from discussions on the creation of a Jewish state to announcements about football training at Jewish sports clubs.

At that time the main mouthpieces of the Zionist movement in Azerbaijan and the Caucasus were the Caucasian Jewish Herald newspaper and Palestine magazine. Meanwhile, issues such as The Situation of Jews in the Diaspora, The Jewish Issue at the Peace Conference, and Palestine and the Jews were hotly discussed within the Baku Zionist organisation.

Preparing for Palestine

However, there was a general concern about the possibility of resettlement becoming uncontrolled and haphazard. Eager to prevent this, the Second Caucasian Zionist Congress adopted the following resolution:

Taking into consideration the fact that it is impossible for all the Jews to immigrate to Palestine and recognizing the need for a gradual and strictly planned organization of this process, the Congress calls upon the entire Jewish population of the Caucasus to refrain from any precipitous and premature attempts to move to Palestine immediately. At the same time, the Congress suggests that measures be taken to prepare and organize the Jews of the Caucasus who want to move to Palestine.

Echoing this, Zionist leader S. L. Itskovich conducted a series of lectures on the challenges of cooperation and Jewish settlement in Palestine. He felt that the first to be resettled should be farmers, then construction workers and, finally, skilled tradesmen, arguing that by resettling the most able Jews first a nucleaus could be created around which less productive settlers could settle later.

A group known as the Palestinian Commission worked to register and assign Jews intending to resettle to Palestine that were skilled in agriculture and the use of agricultural machinery. Labour cooperatives known as gakholuts were set up whose aim was to prepare the people for Palestine and Palestine for the people. They were required to give detailed information about labour resources and to develop agriculture and industry, and were also tasked with creating a network of information bureaus in the Caucasus in cooperation with the central information bureau in Constantinople.

The District Palestinian Commission under the Zionist Organization in the Caucasus began a regular publication entitled Palestine dedicated to issues of emigration. The first issue included articles called Our Goals, The First Steps and Upcoming Trade and Industry Prospects of Palestine.

The founder of Zionism Theodor Herzl in 1897. In the background is a copy of Kavkazer Vokhlenblat, a weekly publication of the Baku Zionists in Hebrew. Photos: Wikimedia Commons

The founder of Zionism Theodor Herzl in 1897. In the background is a copy of Kavkazer Vokhlenblat, a weekly publication of the Baku Zionists in Hebrew. Photos: Wikimedia Commons

Aside from publications and informational meetings, Zionist organizations decided to make use of film to improve people’s perceptions of Palestine. For example, the Palestinian cinematographic society Minor gave permission for a film called Modern Jewish Palestine, produced in 1919 by the Bezalel Arts Academy in Jerusalem, to be shown in Ottoman cities such as Constantinople (Istanbul), Smyrna and Thessaloniki. The film proved popular and soon after it was also screened in Baku, Tiflis (Tbilisi) and Batumi.

Soon, more concrete plans for realizing Zionist dreams were under way. On 6 February 1920, Azerbaijan newspaper published the following report, entitled Resettlement to Palestine:

The local Palestinian information bureau informed members of the Baku Jewish community that at present it is possible to obtain permission for Jewish craftsmen of various categories who have the means to travel (about 25 thousand roubles) to travel to Palestine. The District Palestinian Commission has already sent the first list of persons wishing to move to Palestine in order to obtain a travel permit. The lists will be sent out by 20 February. The District Palestinian Commission in Baku plans to send a special delegation to Palestine in the near future to explore a number of immigration, trade and industrial issues.

Mass exodus

From 1899 to 1920, when this report was published, Zionist activities had already enabled several hundred Jews to leave Azerbaijan. However, in 1925 the Zionist movement was quashed. Later in the Soviet era, from 1972-1980, approximately 12,000 Jews managed to leave Azerbaijan for economic and ideological reasons. By 1989, according to the last All-Union Population Census of the USSR, there were 30,800 Jews living in Azerbaijan.

Since that time, there has been an increase in the repatriation of Jewish citizens to Israel, especially following the start of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, the decline in production and the unstable public and political situation in the 1990s. The Aliyah (Jews who chose to emigrate – Ed.) from Azerbaijan numbered 466 people in 1989, 7,905 people in 1990, 5,676 people in 1991, 2,777 people in 1992, 3,500 people in 1993, 2,270 people in 1994 and 177 people in the first half of 2003.

As a result of this mass exodus, which was made up primarily of Ashkenazi Jews from Europe, Mountain Jews, who have lived in the territory of Azerbaijan for millenia, began to once again be the dominant Jewish population in the republic. While many of them find themselves at home in Azerbaijan, for many of their fellows the 140-year-old Zionist dream of returning to their ancestral homeland came true.

About the author: Moisey Bekker is a senior researcher at the Institute of Law and Human Rights un-der the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences