Ganja has long held the spot of Azerbaijan’s second city after Baku, though for years, getting between the two cities has been a daunting task for travellers. On 30 December 2018, this finally changed, as a new highspeed express train began service. It is now possible for just 15 manats to make this trip in only 4.5 hours. In case you wonder what you could do if you took a trip to Ganja, David Maximovich recently spent 48 hours there and shares about his experience.

An American colleague of mine came to Azerbaijan on a business trip a few years back, and while here, was given the opportunity to take a day-trip out to the regions to experience local culture. What he thought would be just a few hours of sightseeing turned into 18 hours of going from house to house drinking tea, eating kebabs, and being introduced to every living relative of his guide. When I later asked him about his experience, he remarked, You know... there is a fine line be-tween hospitality and hospitalization.

Part of his struggle was that he was coming from the West, where time and productivity are central focuses in life, into a more East-ern culture, where life’s emphasis is put on relationships. One cannot build strong relationships without a heavy investment of time. This is often misinterpreted by Westerners as laziness, when in reality, Azerbaijanis are simply greasing the wheels in their system with meat and tea so that when they need to accomplish something, they have a strong network around them to help them do it.

I was talking with my local friend Rufat, who is an Azerbaijani tutor and budding tour guide, about things I’d been learning about Azerbaijan’s history, when he invited me to come with him for a trip out to his native Ganja and explore some of the historical sites there. I was thrilled to jump at this chance, but in the back of my mind, I knew that going back to his old stomping ground was probably going to bring me close to that fine line my colleague had mentioned. I asked where we would stay the night, and Rufat said we’d figure it out. The Western part of me wanted an itinerary, but I knew he had friends and family in Ganja, which in Azerbaijan is more reliable than having a plan. So, having put my brain in Eastern mode, we began our journey.

The city of treasure

The meaning of the name of Ganja is not known for certain, but one theory is that it comes from the old Medio-Persian word ganj, meaning “treasure.” One legend I heard said that the founder of the city, Muhammad ibn Khalid ibn Yazid ibn Mazyad, had a dream about a hidden treasure in the area. In the dream, he was told to dig up the treasure and use it to build a city. Whether or not this was true, I felt like I was on a treasure quest to discover what sort of wonders Ganja had to offer.

Our first stop when we arrived was the Ganja Mall, where a distant relative of Rufat’s runs a little shop called Waffle Mark that sells coffee and desserts. We picked up a couple of Americanos (the cashier got a kick out of selling an Americano to an American), and then walked across the street to check out the Shah Abbas Mosque.

As one approaches, the first thing they see is the impressive twin red-brick minarets that tower above its wall and the surrounding evergreens. An elegant white archway stands between them, which leads into the courtyard, inside of which is a small fountain and the main building of the mosque.

The imam was standing outside as we approached, and we asked him if we could look around a bit. He smiled and led us over to the main door. We removed our shoes and passed inside to the spacious hall. Twelve doors, representing the 12 imams in Shia Islam, were spaced around the white-washed walls, and the light coming through stained-glass windows and chandeliers gave the green-carpeted room a serene, almost mystic feel.

The mosque, the imam explained, which is actually called the Juma Mosque, is often referred to as the Shah Abbas Mosque because it was constructed by order of Persian ruler Shah Abbas the Great, who reigned from 1588-1629. He even designed it with a special tunnel for his personal use that connects it to the adjacent Chokak Hammam bathhouse (now run by the Vego Hotel). At one point, the writer and poet Mirza Shafi Vazeh, whose museum we would later visit, studied at the madrasa (school) that was located at the mosque.

The mosque complex was pillaged and heavily damaged during fighting with the Karabakh Khanate in the late 1700s but was later restored. The building fell into disrepair over the next few hundred years, but in 2008, it was fully remodeled into its current condition.

We thanked the imam and walked around to the back side of the mosque, where, in a similar red-brick style, lay the tomb of Javad Khan. He had been the ruler of Ganja around the turn of the 19th century. Unfortunately, his small khanate was caught up in the larger power struggles between Russia and Persia. Ganja, which leaned towards Persia at the time, was besieged by Russian forces, and in January of 1804, Russians entered the city and killed Javad and his sons. The place of his burial was forgotten until Soviet times, when workers excavating a fountain near the mosque uncovered his grave marker. In 2005, a proper tomb was erected with help from the Heydar Aliyev Foundation.

The hospitality factor

As we approached the main street again, we heard a shout of Sadigov, what are you doing? Across the road stood Rufat’s uncle Tahir (the dairy farmer we wrote about in Preparing for Winter: A Day in the Life of Dashkesan’s Dairy Farmers, also in this issue). We crossed over to meet him, and within two minutes, our planned historical tour was shelved in favour of lunch at Tahir’s house.

When we arrived, Tahir’s two young sons greeted us, and his wife quickly set the tea on. There was already a large pot of liver and onions going on the stove. We chatted about New Year’s and new cows. Tahir’s older son changed the language on my phone to Azerbaijani (I’m still trying to figure out how to change it back) and started playing games I didn’t even know I had on it, while his younger one admired my camera. Despite the unproductiveness of the time, it was a lot of fun. Three hours later, we packed up and headed out, not to continue the tour, but to head over to the house of Namik Hasanov, a good friend of Rufat’s father who heard we were in town.

While this stop also involved a fair amount of tea and chatting, Namik also knew that my desire on this trip was to see a bit of Ganja and learn about its history, so soon Rufat, Namik, his son Elton and I piled into his Lada. Let me tell you, if you want to have an excursion that you will never forget, you should travel by Lada!

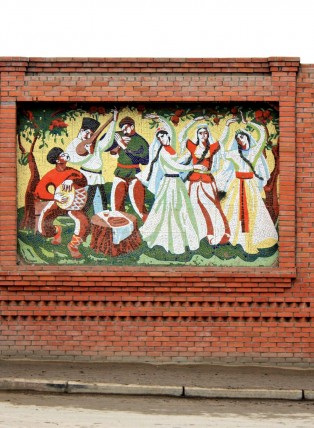

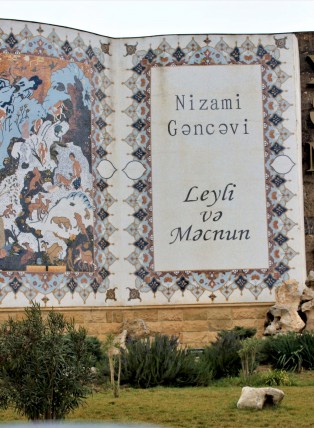

Namik whipped a J-turn and then gave me a fast and furious tour of Ganja’s public art. Throughout the town, there are a number of statues and plaques in honour of historical figures such as Javad Khan and Fatali Khan Khoyski (the first prime minister of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, whose first capital was Ganja), and a number of murals dedicated to the poets Mirza Shafi Vazeh and Nizami Ganjavi and their writings. On the highway entering Ganja from the east is a series of enormous books, each uniquely decorated and displaying the title of one of Ganjavi’s works. The first of these, entitled Sirlər Xəzinəsi (Treasury of Secrets), reminded me of my quest.

Unfortunately, darkness cut our tour short, and we returned to Namik’s home, where his wife Metanet had prepared us a meal fit for a king. The main dish was uch baji, whose name translates as “three sisters,” a reference to the trio of peppers, tomatoes and eggplants that are stuffed with lamb and spices. This was served alongside shah plov, a lamb and rice dish with a special bread crust, dovgha, a soup of yogurt and greens, lentil soup and a variety of pickled vegetables. We feasted and enjoyed each other’s company well into the night, until finally my full belly and the lateness of the hour forced me to retire.

When I awoke, I was still feeling a bit full, but entered the dining room to find the table spread with eggs, bread, sweet rolls, cheese, fresh butter, sausage, and a hot kettle of tea. We ate a slow breakfast, and then set out for a continuation of our tour.

The Bottle House was built using over 48,000 glass bottles (seen in the black parts of the house here), as well as other pieces of artwork

The Bottle House was built using over 48,000 glass bottles (seen in the black parts of the house here), as well as other pieces of artwork

Our first stop was the bottle house. This building was constructed by Ibrahim Dzhafarov in 1967 using over 48,000 glass bottles, as well as mirrors, stones, and other random elements. As Namik explained it, he built it in honour of his younger brother, who had never returned from the Second World War, partially in hopes that if his brother were still alive, he would hear about it and come find him. As he told me this, I stood contemplating the mural of the young soldier under the eaves and found myself impressed not only by the amazing creativity that went into the house, but by the amazing love that would compel a man to such an undertaking.

From there, we went to the Ganja State History and Ethnography Museum. Here, for only 2 manats, we were able to walk through the history of Ganja from prehistoric times until the present. There were thousands of artefacts, documents, and pieces of artwork on display, including exhibits to Nizami Ganjavi, Javad Khan, Mirza Shafi Vazeh, the world wars, the conflict in Karabakh, and local rug weaving traditions. Admission included a guided tour, though the guide only spoke Azerbaijani and Russian, so if you do not know those languages, having an interpreter would be helpful. Many of the displays, however, contained descriptions in English. The tour guide did say that they have an English-speaking guide that volunteers from time to time, but one should call ahead if they want to prearrange this.

Sages of old

Having noticed the common themes of Nizami Ganjavi and Mirza Shafi Vazeh all over the city, I was curious to learn more about these figures and why they were so dear to the people of Ganja. Our next stop did not disappoint, as we went to the tomb and museum of Nizami Ganjavi (1141-1209). Both buildings were quite beautiful and displayed quotes from his writings.

In Ganjavi’s day, the most prestigious work a poet could find was that of working in the royal court, writing poems to feed the king’s fancy. Nizami never held such a position, but instead was more of a freelance poet, choosing instead to write things that addressed the wants and concerns of average people. He was a literary trailblazer, as he blended both lyrical and narrative styles to produce enchanting epic tales. His most beloved works are five long poetry collections known as the Five Treasures. In these, he explores themes of love and apathy, war and peace, life, death and spirituality, and emphasizes the need to contemplate one’s purpose and eternal destiny.

These contrasts really came to life as we left the grandiose gravesite and drove to Nizami’s former house, which was small by any standard, and whose broken walls were surrounded by a crumbling stone fence on a side street far away from the marble sidewalks where tourists strolled. It was a good reminder that while the poet’s words lived on, he himself was gone, having already reached his eternal destination.

We then headed for our final stop of the day, the Mirza Shafi Vazeh Museum. Entrance was free into this facility, as was a guided tour, again in Azerbaijani or Russian. The large, open interior of the building was adorned with dozens of verses from the famed poet, all written in Azerbaijani, along with corresponding artwork. While Vazeh (1794-1852) was a Ganja native, his works gained notoriety first in Europe after Friedrich Martin von Bodenstedt, a travelling German poet, translated and published his poems in a book called Die Lieder des Mirza Schaffy. His works were read widely enough to influence the likes of Johannes Brahms, Pyotr Tchaikovsky, and a number of other great composers.

|

Words of wisdom

Mirza Shafi Vazeh was both a writer and a philosopher. In his search for understanding, he penned a number of rules of life. The following are a few examples:

It is better to be a good unrecognized genius, than to live a deceptively honorable life and pass yourself off as something big, when you are really nothing.

Those who do good will be rewarded, but while you are doing good, you don’t need to dream about the reward.

He has not loved, who hasn’t measured his passion and poured it out to its very last. Those who haven’t taken love far have not gone far in love.

Do not be a slave to someone else’s opinion, but judge everything for yourself.

The majority of people prefer darkness. For many, blindness is more peaceful than insight.

Sing such songs as if the day when death comes to touch your cheek is still far away. But live and love as if death is at your doorstep.

The hotter a fire is, the less it smokes. The truer love is, the less you need to talk about it.

|

We finished off our day with a meal at the Paris Café, a quaint restaurant and karaoke club with a decent international and Azerbaijani menu, which again was owned by a close friend of Rufat’s. We then said goodbye to Namik and his family, and headed back to Baku.

Reflections

As I looked back on this trip and my quest for treasure, I determined that I had indeed found it. But it was not the material treasure we crave in the West. It was an Eastern treasure. I had found the wisdom of ancient sages. I had discovered a brotherly love that would create a masterpiece of art you could live in, all as a beacon to one who was lost. And I found a new appreciation for relationships and the need to invest oneself in them above punctuality and productivity. Yes, I had found my treasure, and I can store it in my heart for years to come.

.jpg)