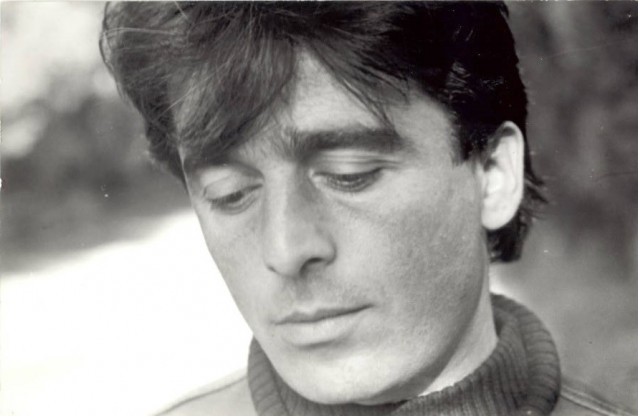

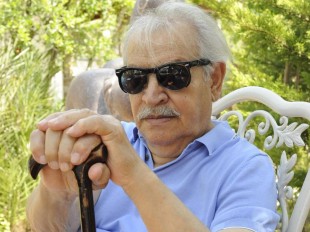

I was given a little book a while back entitled Sənət Fədaisi, or A Victim of Art. It was written by Irada Abdullayeva, chronicling the life of her late husband, actor Ferman Abdullayev. He was a man of many talents, though his greatest passion was performing. Over the years, he played roles in genres ranging from comedy to drama to war on both the stage and the silver screen. He was also a husband and a father. He cared deeply about not just his own children, but the children of his nation. Now, years after his death, his life has left a legacy in Azerbaijan, though probably not the one that he expected in his younger years when he first began to study theatre.

I had the chance to meet Irada khanim, who to this day has a twinkle in her eye when she mentions Ferman, and heard more of their story. Their love for each other, which stood firm through some of the most difficult years Azerbaijan has seen, was kindled by their commonalities. Both of them have roots in the Ingiloy community in northwestern Azerbaijan, and shared a passion for drama.

The early years

We actually met in theatre. I was working at the Sheki State Drama Theatre. It was very popular back then. But they only accepted a small group of people. Seven people. Back then, in the Soviet era, when you finished university, they gave you work and sent you to a specific place. They were going to send me to the Sumgayit Drama Theatre, but I didn’t want it. I’m from Qakh, close to Sheki. My parents were sick at the time and I wanted to be closer to them. It was very hard to change the documents. I had to go to the hospital (to get proof that they were sick – Ed.) and take the documents to the Ministry office, and then they changed them for me. I was then able to work at the Sheki Drama Theatre and visit my parents often. That was when we met each other. I worked in the theatre for one year, then we got engaged and got married. Then, he didn’t want me to keep working in that theatre because he hoped we would move to Moscow. He was always saying, “I’m going to go to Moscow. I’m going to go to Moscow.” He wanted to work in the Moscow Drama Theatre. His heart was there. He told me that when we moved there, he wanted me to work in the theatre there, but I knew that it wouldn’t happen because my Russian language skills weren’t very strong. In theatre, you have to be able to speak.

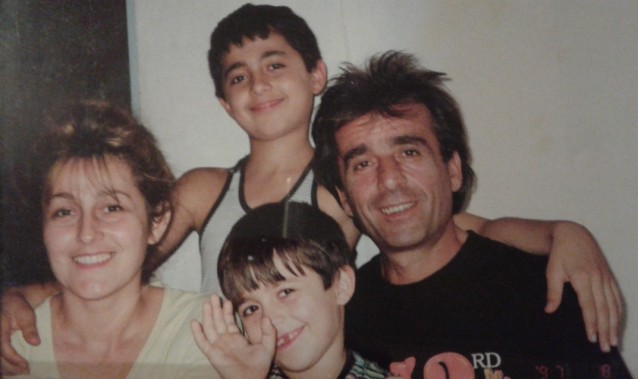

But then we had kids, and while they were small it was hard for me to work in the theatre anyway. But those times were good. He had plenty of work, we were always laughing, I was always entertaining his coworkers.

Ferman’s acting career continued to grow in the 1980s as he took roles in Soviet films like Under Unusual Conditions and The Empty Seat. The 1990s brought with them the fall of the Soviet Union and the war in Karabakh, and life in Azerbaijan turned on its head. Suddenly, things that had been taken for granted ceased to exist. All across the collapsing Soviet Union, communism was being replaced with makeshift democracy and capitalism, and stability was giving way to lawlessness and hunger. As countless people struggled to put life back together, and powerful men laboured to create a new and independent Azerbaijan, children were often an afterthought. They were falling through the cracks in this chaotic new world. Yet in one short generation, these children would be the ones taking over the reins of Azerbaijan. Ferman saw this and felt that someone needed to step up and help lay a foundation for these children, so they would be ready to meet the future head on.

A new idea for a new era

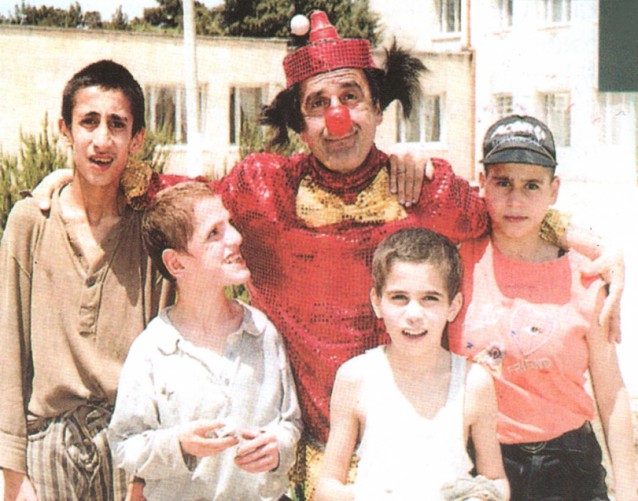

After much thinking, he came up with the most unlikely of solutions: he would become a clown. When he presented his colleagues with the idea for a television program called Shurum Burum (which aired on a channel that no longer exists called Sara TV), they thought he was crazy. They couldn’t understand why someone who had seen so much creative success would humiliate himself and give up the prestige of what he had been doing in order to be a clown for children. As far as they were concerned, he could not have made a lower, more undignified career choice. And at the time I agreed with them, said Irada.

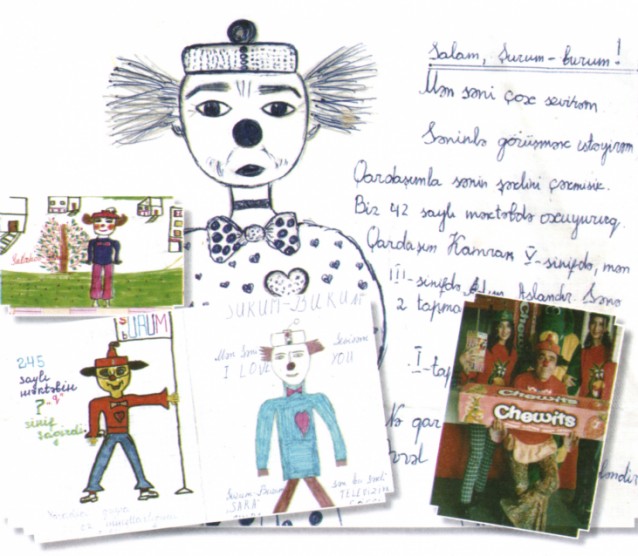

Yet despite the objections and predictions of career suicide, Ferman donned a red nose, bowtie and crazy hat, and set out to change the world. For both children and parents, Shurum Burum quickly became a hit. He not only entertained the children with his funny antics, but also taught them valuable life skills, like how to safely cross the street (in this author’s opinion, probably one of the most useful skills a person could have in Baku), and the dangers of laziness and the benefits of hard work. He encouraged them to listen to their parents and do their schoolwork and taught them interesting facts about nature and other topics.

After Ferman’s passing, Irada heard from many young adults who had grown up watching Shurum Burum. They shared how much he had given them in their younger years. One fan shared When we were little, we didn’t want to listen to our parents or do what they told us, but if Shurum Burum said it, we would do it. He said, “Study your lessons,” so we studied our lessons. He said, “Listen to your mom,” so we listened to her.

Ferman also sought to give mothers a helping hand. Without all of the institutions of the Soviet Union to help with childrearing, not to mention their financial struggles, many were at a loss for how to engage with their children. Shurum Burum would encourage them to sit down with their children and do crafts, or to play games or use toys that stimulated their thinking. He gave them ideas for free activities they could do with the little things they had around them, and ways that they could have fun without spending any money.

He encouraged parents to answer their children’s questions with real answers. For example, he would say if a child saw a car and said, What’s that? the parents shouldn’t call it a “beep beep,” they should call it a car. He explained how children are ripe for learning and development, and parents should be speaking into their lives and helping them grow. This also meant instilling the values into the children that parents wanted them to hold when they became adults.

Irada shared how he was consistent with this both on and off the screen. At home, he always tried to reach his sons at the level of their identity. If they broke something, for example, he would say, You are a man. And men don’t break things. Or if they didn’t want to do their homework, he would say, You are a man, and men are smart, so you should study. He was trying to form their character while it was flexible so it would hold the right shape when they got older.

During this era, Ferman also introduced their son Elvin to the world of acting. First, at the age of three he was in a small television commercial. Then, at the age of six, he got to join his father playing Shurum Burum. He took part in the show with him and asked Shurum Burum questions that he answered for the audience. These planted seeds in Elvin that would bloom many years later.

Back to grownup things

Shurum Burum, contrary to what many had thought, was not the end of Ferman’s career. He did return to making feature films in the mid and late 1990s. Yet even here, the new post-Soviet reality impacted the roles he played. One of the most noteworthy films he acted in during this time was The Yellow Bride (Sari Gelin), set during the Karabakh War. The title of this movie came from a folk song beloved by both Azerbaijanis and Armenians. In this film, Ferman plays the role of an Armenian officer, and he and the rest of the cast tell a tragic tale of the absurdity of war. Eventually, an Azerbaijani soldier and Armenian soldier pair up and run away from their fighting units. They end up encountering a mysterious and silent woman of unknown origin. She is the lone survivor at a massacred wedding, and her blond hair and yellow bride’s dress remind the men of the haunting song of love and death. Together these three try to escape the madness. (You can view the film with English Subtitles here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NlSExfK4Jmw).

Growing up under his father’s wing, Elvin soon felt pulled to follow in his footsteps. Irada was concerned when their son announced that he wanted to go into the film industry. I wanted Elvin to go into economics, but he told me one day that he wanted to be a film producer. The world of arts can be so hard and you have to sacrifice so much, and people can be so cruel. I didn’t want that, but Ferman said, “If he wants to be a producer, let him go and be a producer.” Years later, he has proved himself and is working as a producer for Dream Big Film Company in Baku. He recently released Azerbaijan’s first horror film, Khennas.

Irada was not wrong in her estimation of the stress of the film industry though. It eventually caught up with Ferman and he became sick and he passed away on 6 March 2013 at the age of 59. Many felt his loss. Letters poured in to Irada from those who had known him and been touched by him. In her book, a full 30 pages are devoted to letters she received from those that knew and admired him. But letters and memories do not replace a man. Now, life for Irada must continue without him. When I was studying in university, I thought that I wouldn’t be a good actress, so I decided to also be a journalist, and later studied linguistics. Right now I work as a translator and a teacher of Azerbaijani for foreigners.

Though she doesn’t act anymore, she does sometimes find her way back into the world of drama. Recently, she found herself helping with casting, costume and makeup for a short local film called Forgive Me, set around the spring Novrus holiday telling the tale of a young man who tries to find purpose in life between the tug-o-war of a broken family, an unexpectedly dangerous job, and the love of his life whose parents distrust his father. You can view it with English subtitles here: https://youtu.be/9HVl1Ao2KNM.