Pages 36-44

Pages 36-44by Dr. Gasim Hajiyev

Most of modern-day Azerbaijan was once the Kingdom of Albania – not to be confused with the country of Albania in the Balkans. Caucasian Albania included the whole of Karabakh, both Upper or Mountainous Karabakh, now occupied by Armenian forces, and Lower Karabakh. The city of Barda in Lower Karabakh was at one time Albania´s capital. Dr G.A. Hajiyev, director of the Bakikhanov History Institute´s Karabakh History Department, gives an overview of the history of Karabakh and Albania up to the 13th century.

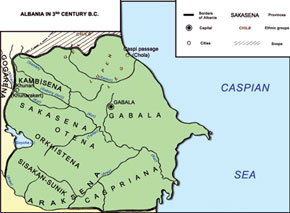

Caucasian Albania was formed in the 4th to 3rd centuries BC. According to both ancient Albanian and Armenian sources, the Araz River formed Albania´s southern border. (Today the river separates Iran and the Azerbaijani Republic.) The territory of Caucasian Albania extended from the Araz River to the Kur, and westwards to Agstafa. Albania encompassed several provinces, including Artsakh, modern-day Karabakh.

Albania resists Roman rule

The Romans did not manage to include Albania in their empire as a province. The fact that the Albanians did not lose their independence to the Romans can be seen from Albanian coins. When the whole Caucasus depended on the Roman Empire in the early 2nd century, only Albania was independent. At this time, in the 1st-3rd centuries, Karabakh remained part of the Albanian Kingdom.

Ancient scholars wrote about the economic and cultural history of Caucasian Albania. Albania is mentioned in Strabo´s Geography, Pliny the Elder´s History of Nature, Pomponius Mela´s Description of the World, Plutarch´s Parallel Lives, Tacitus´s Annals, Ptolemy´s Geography and Cassius Dio´s Roman History, amongst others.

Archaeological excavations provide the main sources of information about the history of Albania during this period. Albania had both a nomadic population and a settled population of farmers. In the last centuries BC and early centuries AD the Kur and Araz basin were inhabited by peoples named the Saks, Massagets and Huns by ancient authors.

Agriculture thrives in Karabakh

Karabakh was one of the regions of Albania where the economy developed. The population of Karabakh were settled farmers who cultivated barley, wheat and millet. Wheat was kept in underground pits and earthenware pitchers and grain was processed with hand-mills. Figs, olives, walnuts, pomegranates, cherries and peaches were also cultivated in Karabakh. This all speaks of settled farming. The high alpine steppes and river basins had an important influence on the development of animal husbandry. Special local breeds of horse were sent to the rest of Albania and to other countries. Cattle were also reared in the region.

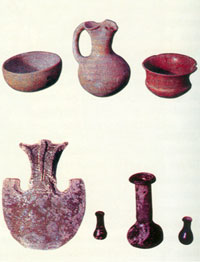

Archaeological excavations in Karabakh have revealed tools and evidence of domestic crafts in the Albanian period. Pitchers, clay dishes and metal items were found in ancient graves. There is evidence that iron, bronze, gold and silver were worked in ancient Karabakh. Wool and silk were also woven here.

Network of roads and cities in Albania

There were cities, towns and villages in Albania. Second century geographer Ptolemy reported 29 cities and settlements in the Kur basin. They were connected by roads. Authors of the period wrote about roads crossing Albania and Iberia, which is today eastern and southern Georgia, connecting them with the whole world. Roman commanders Gnaeus Pompeus Magnus and Mark Antony´s Publius Canidius Crassus used these roads to attack Iberia and Albania in 65 and 36 BC respectively. Strabo records that the peoples on the north coast of the Caspian Sea traded with India and Babylon. The sea was another trading route and ancient sources frequently mention the Caspian.

A Greek inscription in the village of Boyuk Dahna near Sheki is proof of links between the ancient Roman world and Albania. Eli Yason dedicates the inscription to his patron. Research has shown that Eli Yason came to Albania to trade. The interest in the east shown by merchants from the Roman Empire may have launched the major trading routes.

Excavations in Karabakh have yielded plenty of imported glassware, coins and gems, yellow sea shells, earrings and beads, bronze lamps and silver dishes which are all evidence of trade. They show that Caucasian Albania had trading links with the west and east as well as Parthia. Traders travelled along the Parthian and Atropatena highways.

Albania at its height

In the 4th to 7th centuries Caucasian Albania covered a large territory. It was bordered by the Greater Caucasus Mountains in the north, the Araz River in the south, the Caspian Sea in the east and Iberia (the eastern part of today´s Georgia) in the west.

Albania had 11 regions or vilayats: Chola, near what is now Derbent in southern Dagestan, which was the first residence of the head of the Albanian Church, the Catholicos; Lipina, the area south of the Samur River; Cambissena near the border with Iberia; Qabala which was the first capital of Albania; Ajary, south of Qabala; Sheki which included the modern-day Balakan, Zaqatala and Sheki regions; Paytakaran, also known as Caspiana or Balasakan, which are today the Mil and Mugan plains in central Azerbaijan; Uti, which was later the capital of Albania and the residence of the Albanian Catholicos, also known as Partav and today Barda; Girdman, the area bordering Iberia; Artsakh, modernday Mountainous Karabakh and part of the Mil plain; Syunik also known as Sisian and Zangazur which are now in southern Armenia.

Karabakh was the area between the Kur and Araz rivers, which included the Albanian regions of Uti, Girdman, Sakasen, Artsakh, Syunik and Paytakaran, the Albanian capital Barda, and the rulers´ summer residence Khalkhal.

Both nomadic and settled tribes lived in Albania and the Caucasus as a whole. Turkic tribes were part of the ethnic mix of Karabakh in the 4th-7th centuries. During this period there was assimilation between local and incoming tribes in Karabakh with Turkic tribes forming the majority.

Karabakh becomes a trading centre

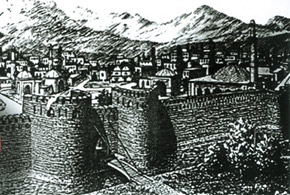

In the 4th to 7th centuries the Karabakh population were mainly settled farmers. The land was fertile and well irrigated by rivers and canals. Wheat, barley and millet were cultivated. Albanian historian Moisey Kalankaytuklu wrote in his Albanian History that horticulture, and in particular melon-growing, were developed in Karabakh. Grapes, cherries, pomegranates, walnuts, olives and saffron were also cultivated and the plant madder was processed here to produce red dye. Animal husbandry, fish-breeding and sericulture were also practised at this time. Karabakh became a centre for handicrafts in the early Middle Ages, too: potters, jewellers, weavers, glass blowers, blacksmiths, stonemasons, wood-turners and other craftsmen plied their trade here. They were competing for business with Asia Minor. Local craftsmen and traders formed towns in Karabakh and other parts of the Kingdom of Albania, which became social and political centres. The towns housed administrative buildings and palaces and were surrounded by fortress walls. The most famous were Qabala, Chola, Barda, Paytakaran, Amaras and Tsiri.

Trade was highly developed in Karabakh during this period. Internationally important roads passed through the South Caucasus, connecting its cities with the Silk Road from the Far East to Europe. Karabakh´s towns developed links with a great number of western and eastern craft and trade centres through the Kur River and the Caspian Sea. Coins from Sassanian Persia, Byzantium and elsewhere, found in Karabakh, are evidence of the region´s broad trade links.

Albanian language

The Albanian language was rich in guttural sounds and had its own alphabet, consisting of 52 signs. Some religious literature was translated from ancient Aramaic, Greek and Pahlavi into Albanian. Albanian King Vachagan III´s Laws and Moisey Kalankatuklu´s Albanian History are the two most prominent extant works in the Albanian language.

In the early 5th century on the orders of King Vachagan III a school was opened in the Albanian capital Barda, where Buddhist children were taught literacy and Christianity.

Christianity

Christianity reached Albania, including Karabakh, at the beginning of the 4th century and became the official religion. The church was governed by a Church Assembly, which involved the king, church leaders, priests and the nobility. The head of the Church Assembly was the Catholicos. From the 5th century onwards the central province of Albania, Karabakh (Uti), became the kingdom´s political, economic and cultural centre. In 446 the capital city of Albania was moved from Qabala to Barda. The Albanian kings had to fight off foreign attackers, but managed to protect their independence. King Vachagan III (487-510) strengthened the role of Christianity to bolster his government. During Vachagan III´s reign, in 488, the Albanian Laws were written in Albanian as a foundation of the country´s political and religious life. In 552 the residence of the Albanian church leader, the Catholicos, was moved to the capital Barda.

War

In the 6th century Albania became a theatre of war among the Persian Sassanian Empire, Byzantium and the Kingdom of the Khazars. The Sassanian Empire and Byzantium agreed a treaty in 591 under which Albania was governed by a local dynasty under the rule of the Shahanshah or Sassanian Shah. Albania, including Karabakh (with its regions of Uti, Paytakaran and Artsakh) became part of the northern province (janishinlik) of the Sassanian Empire.

In the early 7th century (603-629) a fresh war between the Sassanian and Byzantine empires badly damaged towns and villages in Albania, including the capital Barda. The Albanian ruler Javanshir signed a treaty with the Byzantine emperor, Tiberius II Constantine, to save the country´s political and economic power and avoid a senseless war.

Later, realising that Byzantium was now weak, Javanshir adopted Arabian guardianship over Albania in 667. In this way he managed to retain a degree of independence for Albania and protected it from armed attack and plunder. Javanshir maintained the development of the economy, craftsmanship and culture in Albania. It was on his instructions that Moisey Kalankatuklu wrote the Albanian History. Javanshir also valued poetry, architecture and music and Karabakh and its capital Barda became an important cultural centre of Albania during this period.

Islam

As a result of Arab aggression, in the 7th century the southern part of Azerbaijan (modern-day north-western Iran) became part of the Arabian Caliphate, while Albania became a vassal of the Caliphate.

A new religion, Islam, spread in Karabakh at this time. Most of the population became Muslim, while a small minority retained their Christian faith. Taking advantage of the situation, the head of the Armenian Church, Catholicos Ilya, betrayed the Albanians, convincing the Caliph, Abdulmalik, that the Christian Albanians were planning a rebellion against him. Rather than get to the root of the problem, the Caliph had the Albanian ruler and Albanian Catholicos executed, abolished the Albanian state and subordinated the Albanian Church to the Armenian Church. This began a process in which the Albanians of Upper or Mountainous Karabakh lost their Albanian identity and became Armenian. The population of Mountainous Karabakh knew about their Albanian roots until the 19th century.

Part of the Caliphate

In the late 6th and early 7th centuries the Albanian Church adopted Nestorianism (the doctrine that Christ existed as two persons, the man Jesus and the divine Son of God), while the Armenian Church adopted the Monophysite doctrine (that Christ had only one nature, the divine). Rivalry between the Byzantine Empire and the Caliphate grew in the South Caucasus, as the Caliphate tried to separate the region from Byzantium. The Caliphate tried to convert the population to Islam as part of their attempts to control Albania.

The struggle for Albania intensified at the beginning of the 8th century. The position of Byzantium began to weaken while the Kingdom of the Khazars was growing in strength. The Arabian Caliph or ruler, Abdulmalik (685-705), boosted his authority through economic and military reform and conducted successful operations in the border areas between Byzantium and the South Caucasus. He began to establish the Caliphate in Albania, which was of economic and strategic importance.

Abdulmalik sidelined the Albanian ruler. Barda became the residence of the Arabian Caliphate´s governor and from 705 the territory of Albania was called Arran.

The 8th century saw the start of a new era in Karabakh and Albania as a whole. Christianity was on the wane and Islam took over. The more progressive Islam prevailed over Christianity and other religions in Karabakh. Most of the Albanian population became Muslim, with only a few retaining their previous belief.

The Caspian countries became international trade centres during the Caliphate´s rule. This in turn influenced the development of towns in Karabakh; they became large centres of trade and craftsmanship. Some towns in Karabakh had populations of more than 100,000. Karabakh was connected by rivers to the sea which made trade easy with the countries to the north of the Caspian Sea and along the Kur River. During this period, too, Karabakh was famous as an enormous centre of craftsmanship and trade. The growth of trade was an essential source of income for the Caliphate in the 8th and 9th centuries. In the 9th and 10th centuries Karabakh flourished, enjoying broad trade relations with the countries to the north via the Caspian-Volga route and the Dnepr and Don Rivers.

Merchant caravans came to Barda from many countries, especially from Europe and the east. The famous Barda bazaars played a significant role in international trade and in the development of the region.

Copper, silver and gold coins have been found in different areas of Karabakh. Moreover, five large treasure

Sheykh Babi Yakub´s mausoleum and ruins of ancient mosque. The remains of bath houses and other buildings from a large Muslim religious complex can be found here 1273-74

Sheykh Babi Yakub´s mausoleum and ruins of ancient mosque. The remains of bath houses and other buildings from a large Muslim religious complex can be found here 1273-74 As the Caliphate grew in power, scientific and literary works were written in Arabic and Christian schools replaced Muslim ones. As elsewhere in the east, cities were rebuilt in a new style and mosque complexes were constructed.

Although the ethnic pressures caused protests in Karabakh, the economy continued to grow and Karabakh enjoyed a renaissance.

The fiction that began with the 1st century geographer Strabo that Azerbaijani territory up to the Kur River belonged to Armenians continued into the early Middle Ages. Armenian "scholars" considered Azerbaijani territory to be an ancient Armenian homeland and called Karabakh "Armenian territory".

Medieval Arab authors (such as Ya´qubi, Al-Kufi, Al-Istakhri, Al-Muqaddasi and Yaqut Hamavi) refer to Arran, including Karabakh, as Azerbaijan; the people of Karabakh spoke the "Arran language".

From the 9th century onwards Karabakh became well-known in the Near and Middle East for its scholars. They were educated in the famous scientific centres of the Islamic world and worked both in Azerbaijan and elsewhere. Karabakh scholars were mathematicians, engineers, doctors, historians, lawyers, poets, orators, astrologers and politicians.

Independent feudal states

In the late 9th century independent feudal states were formed in the northern territories and other outlying parts of the Caliphate. Karabakh became part of Sajis, which was ruled by a Turkish dynasty.

The Deylamis seized power from the Sajis in 942 and founded the state of Salaris. In the early Salaris period Karabakh was economically, socially and culturally developed as a central region of the country.

Barda´s wealth was always attractive to the Rus in the north. In 943-44 the Rus sailed across the Caspian and up the Kur River and attacked Barda. They sacked the city but were forced to leave after meeting resistance from the population.

In the 10th century the Shaddadis state was founded. The founder of the Shaddadis dynasty, Muhammad ibn Shaddad, defeated the Salaris and his son Ali Lashkar took power in 971 (971-1075). The Shaddadis took over the whole of Arran, including Karabakh. But after a short time, in 982, Shirvanshah Mazyadis took advantage of the weakness of the Shaddadis and captured part of Karabakh. But Shaddadis ruler Fazl ibn Mahammad managed to wrest Karabakh to his rule in 993. In the 1050s the Seljuks subordinated Shaddadis Karabakh. The attacks did not stop, however. Alans from the north attacked Karabakh in 1062 and 1065, plundering the area and taking plenty of prisoners.

After the Caliphate was broken up, the princedoms of Syunik and Artsakh-Khachen were formed in Karabakh. The Khachen princedom flourished during the reign of Hasan Jalal (1215-61). The chronicles and monuments of the period describe him as the "Prince of the Hachen Countries", the "Grand Prince of the Hachen and Artsakh Countries" and the "Emperor of Albania". The most important example of Albanian architecture, Gandzasar monastery, was built during Hasan Jalal´s rule.

Many of Karabakh´s Christian Albanians were armenianized to the extent that most of the population of Syunik and Artsakh became Armenians. However, the first president of the Armenian Academy of Sciences, I.A. Orbely (1887-1961), wrote that the Khachen princedom was "part of ancient Albania".

Karabakh became part of the Azerbaijani Atabeys state in the first quarter of the 12th century. In 1136 Seljuk Sultan Masud gave Arran as igta (land granted to army officials for limited periods) to Atabey Shamsaddin Ildaniz (Eldagiz). Eldagiz´s residence was situated in Karabakh. In a short time he won over the local rulers and became independent of the sultan. He gradually took over the whole of Azerbaijan.

Coins and other items belonging to the Atabeys have been found in archaeological excavations in Karabakh. They show that Karabakh was a political and economic centre of the period.

Literature

Q.M. Ahmadov, Qedim Beylaqan, Baku,

K.G. Aliyev, Antichnaya Kavkazskaya Albaniya, Baku, 1992

Z.M. Bunyadov, Azərbaycan VII-IX əsrlərdə, Baku, Elm - 2005

A. Falviy, Pokhod Aleksandra, Moscow, 1962

R.B. Goyushov, Azÿrbaycan arxeologiyasi, Baku, 1993, Amarax-Aghoghlan, Baku, 1975, Khristianstvo v Kavkazskoy Albanii, Baku 1984

Q. A. Hajiyev, Barda shaharinin tarikhi, (b.e.a.III-b.e.XVIII asri), Baku, 2000

Moisey Kalankatuklu, Albaniya tarikhy, Baki, 1993

Moisey Khorenski, Istoriya Armenii, translated by N.Yemin, Moscow, 1893

T.M. Mammadov, Qafqaz Albaniyasi ilk orta asrlarda, Baku, 2007 and Kavkazskaya Albaniya v IV-VII vv., Baku, 1993 Ptolemy, Geography

A.M. Radzhabli, Numizmatika Azerbaydjana, Baku, 1977

E.A. Rakhomov, Bashni-movzelei v Barde i ikh nadpisi, Baku, 1936

Strabo, Geografiya v 17 knigakh, translated by G.A. Stratonovskiy, Leningrad, 1964

M.A. Seyfeddini, R.Z. Aliyeva, Parfiya dovleti. (Parfiya dovletinde pul sistemi ve sikke zerbi), Baku, 2004

K.V. Trever, Ocherki po istorii i kulture Kavkazskoy Albanii, Moscow, 1959

X. Xalilov, Qarabaghin elat dunyasi, Baku, 1991