As someone with a background in international affairs, I was interested in the Nobels, in their past and in particular the time they spent living in Baku when Azerbaijan was part of the ‘Russian Empire. The idea of restoring Villa Petrolea matured over a number of years, spontaneously really,’ Dr Bagirov tells me. ‘Thisis how it happened: I met the president, Ilham Aliyev, in 2002 – at that time he was first vice president of the State Oil Company – and he told me that Michael Nobel had sent him a letter. Michael Nobel was chairman of the Nobel Family Society in Stockholm. The family were interested in what life had been like for their ancestors in St Petersburg and in the fate of Villa Petrolea, because Villa Petrolea – the Nobel brothers’ family home in Baku – was like a relic for the family.’

This contact with Michael Nobel eventually led to the creation of the Baku Nobel Heritage Fund. Michael is descended from Ludvig Nobel, whose brothers were Alfred, Robert and Emil. Alfred was a chemist and became famous as the inventor of dynamite and founder of the Nobel prizes. He remained a bachelor and had no children, while Emil died young in an explosion in his father’s factory in Sweden. Ludvig and Robert were both industrialists and key figures in Baku’s oil industry and it is from these two brothers that today’s Nobel family are descended.

Villa Petrolea

The Baku Nobel Heritage Fund’s first project was restoration of Villa Petrolea. ‘To be more exact, it wasn’t restoration work, it was reconstruction work, because atthat time only the walls remained, everything else had either been stolen or destroyed,’ there was nothing here at all. The house was home to stray dogs and cats and the homeless. There was no roof. All that we managed to find were beams from that time, the cast-iron staircase and two out of three of the original fireplaces. We kept the exterior as it was. We restored it step by step. We worked in the archives and looked at photographs. Of course, we changed the Dr Bagirov recalls. ‘For the last 15 years interior, because it was a residential house and now it isn’t. It took us two years and we finished the project in 2007; it took almost a year to find the exhibits. Some came from private collectors, antiquarians in St Petersburg and Baku. Others came from Batumi, where there is another Nobel house. It’s also a museum. The architecture is similar but the house is smaller than Villa Petrolea, as the family did not actually live there. A few items were given by the Nobel family and brought from Sweden.

‘Villa Petrolea is the first Nobel family museum in the world, because there is a museum dedicated just to Alfred Nobel, whereas this museum is dedicated to the two other brothers, and their descendants, i.e. Robert, Ludvig, Ludvig’s son Emanuel, who ran the business empire, and the other Nobels. So we are practically restoring historical justice because to keep quiet about the other brothers and to concentrate on Alfred alone, isn’t right. We’re not the only people who think so, the family think so too, as do historians in Sweden, Russia and Azerbaijan, because the brothers Robert and especially Ludvig were no less talented and successful.’

Although it was Robert and Ludvig Nobel who played the major role in developing Baku’s oil, Alfred was involved too. ‘Alfred Nobel was a shareholder in the Nobel Brothers’ Baku Oil Company,

a major shareholder, and at the very beginning of the project he gave the start-up money, i.e. he played a no less important role,’ Dr Bagirov explains. ‘But it was Ludvig who realised at that moment that Baku and the oil industry were something fundamental, that they would change the whole world.

Ludvig was not simply an industrialist and a businessman, he was a systems man, a researcher and a scholar too. He was a member of the Russian Imperial TechnicalSociety, a technical academy of sciences. He was a friend of Mendeleyev, creator of the periodic table, and was presented to the tsar. It was thanks to Ludvig’s efforts that the monopoly on Baku oil was lifted.’

The Nobels and Baku’s first oil boom

‘In the 1860s and 70s oil extraction was still a novelty and many people did not understand the value of oiland its potential as a resource,’ Dr Bagirov continues. ‘Those who did understand tried to make money out of it. At that time, there was a monopoly on the oil industry in the Russian Empire and Baku was not developing. Kerosene was imported here from America – this was Rockefeller. Although oil was first produced industrially here, in 1848, Pennsylvania in the USA was the second place where production began in 1853. And the Americans were more entrepreneurial and they worked quickly; they began to produce kerosene and kerosene was imported to Russia. Russia was a very promising market at that time, kerosene was used in lamps and so on. Thanks to the efforts of Ludvig Nobel this monopoly was liquidated. Through Mendeleyev he gained access to the tsar and the tsar took the decision to lift the monopoly and signed a special decree. The monopoly had been in the hands of an Armenian industrialist by the name of Mirzoyev, but it was liquidated in 1873.’

At around that time Robert Nobel travelled south from the Nobels’ industrial base in St Petersburg looking for timber to make rifle butts for the Nobel armaments factory. He went to Baku and Lankaran, in the south of Azerbaijan, but wrote to his brother, ‘This place is desert, I’ve found wood, but I’ve also found oil. Everything is burning all around Baku.’

‘Robert visited the Atashgah, the Fire Temple outside Baku, and was impressed by it,’ Dr Bagirov says. ‘That’s when he had the idea

of making the Atashgah the symbol of the company. He wrote to his brother Ludvig, who although he was two years younger was head of the Nobel’s industrial empire in St Petersburg. Ludvig, told him to invest the 2,000 gold roubles he had given him for timber and Robert bought a small oil refinery and a small plot of land where there was oil. After this Robert came to Baku only once more because he was rather fussy and didn’t like the desert, the heat, the humidity. At that time Baku had not been developing because of the oil monopoly, it was the back of beyond.

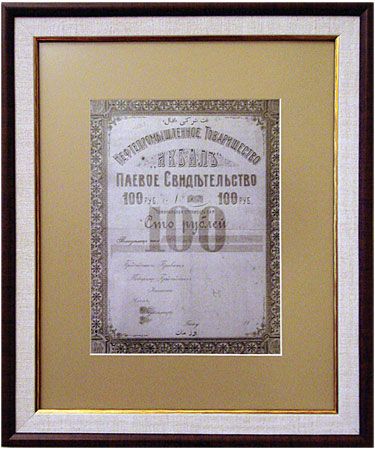

Only thanks to their efforts, Ludvig’s and Robert’s, did the first oil boom begin. The first capitalists appeared and big money came with them, bringing architectural masterpieces. Everything that was built during the first boom by Taghiyev, Asadullayev and other oil barons, it’s all thanks to the oil boom era and pretty much thanks to the contribution of the Nobels.’ <> The brothers set up the Baku Nobel Oil Company in 1879. The company became known as Branobel, an abbreviated version of the Russian name, Bratyev Nobel, meaning Nobel Brothers. ‘In Russian it was called a tovarishchestvo or partnership,’Dr Bagirov explains. ‘They didn’t call themselves pure businessmen, pure capitalists, because their lives show that they had a social conscience. They gave a lot away. They built houses, schools, hospitals for ordinary workers. They were the first to do this. It’s still very rare.

‘Villa Petrolea and this whole park were created in two years. In 1882 they spent almost six months on the architectural plans; Swedish and Italian architects were involved. The French created the park. Soil was brought from Lankaran; fresh water was

brought from Astrakhan; trees and shrubs came from Italy and France.Acorner of paradise emerged here, an oasis, with 10 buildings. The house was the central building. This is where they lived and received guests. They held all kinds of Swedish receptions here. They had an air conditioner, as they brought in 800 tonnes of ice and in the summer the climate here was like in Sweden, plus 15 or 18 degrees Celsius. They had the first telephone in Baku here, a Bell. Many books have been written about the Nobels – in Sweden, England, the USA, Russia and Azerbaijan, including a book by Brita Asbrink which dedicates a whole chapter to Villa Petrolea.’

‘The Nobels devised the first oil pipeline, the first oil tanker, called the Zoroaster. Thanks to their innovations and new technology they improved oil refining and the Nobel Company was the only one in the world that was vertically integrated. That’s when everything from wells to distribution is part of one company,’ Dr Bagirov explains. ‘They had an oil pipeline, tankers, a refinery, distribution. All of Russia and all of Southern Europe were supplied from here. Kerosene went via Russia to Finland and Sweden. The oil was here, nowhere else. Oil wasn’t found in the North Caucasus and Tatarstan until early last century. At the start of the 20th century, 50 per cent of world oil extraction was centred on Baku and some 40 per cent of that belonged to the Nobels. The remaining 60 per cent was divided between the Rothschilds and the Rockefellers. They were also rivals. Standard Oil of New Jersey, Rockefeller’s company, was the largest in the world, like ExxonMobil today. The Nobel Oil Company was the second largest, 10 million tonnes in 1900, 76 million barrels per year. The Rothschilds, Shell, were third.

‘In 1888 Ludvig died in Cannes. He had lived in Baku, but unfortunately after building Villa Petrolea in 1884-85, he was ill. He had practically sacrificed himself to his work and died young. His oldest son became head of the oil and industrial empire. It did not go down all that well here, because both Alfred and Robert thought that they should head the empire, not 29 year-old Emanuel. But clearly they decided not to disobey their brother’s will, especially since Ludvig had trained his son as his right-hand man. At the age of 29, Emanuel became head of the most powerful industrial empire not only in Russia but throughout the world. He was presented to the tsar, received Russian citizenship and a passport, spoke Russian very well and could even have become a state secretary for his services to the fatherland and to industry. But Emanuel preferred Baku to St Petersburg, especially at the start of the 20th century. He was frequently here and oil was now the most important part of the Nobels’ business. There were the armaments and so on, but these were less important. In Baku there was constant competition, the Rothschilds, Rockefellers, etc., the great countries were here, Great Britain, Persia, Russia. Everyone was fighting for Baku oil. And Emanuel was practically a patriot for Azerbaijan and Baku.

‘Emanuel loved Baku, he loved Villa Petrolea, because here he felt growth. St Petersburg was already a museum centre; it had its palaces, its society life, but all this was just beginning in Baku. The main years of the oil boom were 1900, 1905, 1910, when enormous luxury houses, theatres and so on were built. Baku was also becoming a centre of entertainment, a city of pleasure and even of debauchery, because of course with money came everything else – luxury goods, cars, clothes, high fashion, ladies including ladies of the night. Emanuel Nobel liked to visit his friends. For example, he would go to see Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev who had built a fabulous palace which is now the Academy of Sciences. Taghiyev gave the palace to his first wife, held balls there where Emanuel was a frequent visitor. Emanuel fell in love with Taghiyev’s daughter Leyla, who was an Eastern beauty. But the age gap was too great, he was 51 at the time, she was just 21, I think, and nothing happened. Who knows, if the revolution hadn’t happened, maybe something would have come of it.

Revolution

‘Emanuel was to some extent a Romantic, he was naive, and he lostalmost everything, because he did not believe that people could be so destructive. He did not appreciate what the Bolsheviks were, although by 1914 he had already experienced for himself the disease of Bolshevism. Stalin was in Baku and led labour unrest, sabotage at enterprises and so on. Emanuel wrote to his sisters that he thought common sense would triumph and people would not destroy each other. He thought that the workers were too well paid to opt for revolution, while Rothschild and Rockefeller were the opposite, more pragmatic and cynical. They managed to sell up and leave, but Emanuel Nobel lost everything. When the Bolsheviks came to power, the Nobels’ industrial empire was destroyed, both in Baku and St Petersburg, and all the oil fields were expropriated. Anyone who had money was arrested. The Nobels tried to go through the courts and to make contact with Lenin, but they got nowhere. They were left with hardly anything – a house, and some minor accounts in Western banks.

‘Emanuel Nobel left Baku in 1919. He and the oil company’s chief manager were saved by the workers, who told the Bolsheviks and Red Army soldiers not to touch them as they were good bosses. They left Azerbaijan via the North Caucasus, through Yessentuki. According to one story, Emanuel and the manager left St Petersburg dressed as women and crossed the Finnish-Russian border to reach Europe. Another theory is that Emanuel somehow managed to get out via Poland and reach Germany and went from Germany to Stockholm. Emanuel was not broken, strange as it may seem. He continued his life as a bon vivant, something of a playboy. Emanuel had many girlfriends, but never married. He died in 1932, when he was almost 73, having lived nine years without oil and his business empire. All this time he continued to fight and created an entente against Bolshevik Russia to stop the supply of new technology and equipment.’

The other Nobel prizes

‘Alfred Nobel wrote to his nephew, Emanuel, to say that he was proud of him and his achievements as head of the Nobel empire,’ Dr Bagirov says. ‘Alfred was very unhappy in his old age, depressed practically all the time, as he realized the harm his invention of dynamite had caused. Alfred bequeathed everything to his foundation, the special foundation in Stockholm. Many people think that this was because he wanted to redeem himself somehow. I agree, but his brother Ludvig’s fate also pushed him to take this step. Ludvig died in 1888 and the first Nobel Prize was established in his honour in St Petersburg, under the auspices of the Imperial Russian Technical Society.The Ludvig Nobel Prize was funded with money from the Baku Nobel Oil Company. A Gold Medal and some 100,000 dollars in today’s money were awarded for the most outstanding invention or scientific achievement with a practical application in the oil industry. There was an independent jury and Board of Trustees.

‘So Alfred knew about this, when he bequeathed all his money to his foundation. The family, his nephews and nieces, were categorically opposed to this. Alfred’s nephews had expected to inherit this money and started a campaign in the press. It was Emanuel, who as head of the empire, spoke in favour of his uncle’s bequest and convinced his cousins that the will should be respected. It was Emanuel who transferred the first money to the foundation. Alfred had been a share-holder in the Baku Nobel Oil Company, with approximately 25 per cent, and received dividends and lent money to his brother and to his nephew Emanuel. So the first 18 million pounds were transferred by Emanuel Nobel to the foundation’s account. The prize was not awarded until 1901, so there was a battle for four years after Alfred’s death. We have only recently begun to investigate this in the archives in St Petersburg but we can say that between 20 and 30 per cent of the funds which Alfred left to his foundation he either received from Baku in the form of dividends or after his death as contributions from Emanuel. This makes Baku, Azerbaijan, a co-participant in this great venture. That’s the second Nobel prize.

‘Then there’s a third Nobel prize, which not many people know about at all. This was a purely Azerbaijani, Baku prize. It was created in 1907 in honour of Emanuel Nobel, while he was still alive, which is very unusual. This was a prize for development in the oil industry, rather than for scientific achievement. The prize could be awarded to specialists, managers andsoon. It was founded here in Baku, initiated by the Rothschilds and funded by their company Mazut, under the auspices of the Baku branch of the Imperial Russian Technical Society. The prize was awarded four times before the revolution, and like the prize in honour of Ludvig, it was awarded with some intervals, presumably because money was not always available.’

Reviving the Emanuel Nobel Prize

‘Reviving the Emanuel Nobel Prize for the Oil Industry is another objective of the Baku Nobel Heritage Fund,’ Dr Bagirov says. ‘The Nobel family are supportive. The Nobel committee and foundation understand that we are restoring a historical prize, not inventing a new one. We are still discussing this, but I am optimistic. The money in the prize fund will come from sponsors. Obviously there will be an independent jury. We have already agreed with the president of the Azerbaijan Academy of Sciences, Mahmud Karimov, and the prize will be awarded under the auspices of the academy so there will be complete independence. I know that oil companies will take part. We have the support of the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan, SOCAR, we are talking to BP, I think Statoil will join too. It’s important for them because the prize supports oil development and will encourage scientists and specialists. Secondly, we are restoring historical justice.’Nobels return to Baku

The restored Villa Petrolea was officially opened on 25 April 2008. The ceremony was attended by 25 members of the Nobel family, led by Michael Nobel and Thomas

Tyden, the current chairman of the Nobel Family Society, and by a special representative of the Swedish Foreign Ministry. Dr Bagirov and a delegation of 12 family members were received by President Aliyev. During the meeting it was agreed that the Baku Nobel Heritage Fund would work on various projects – the museum, the Emanuel Nobel Prize and a project to recreate the medical centre that was established at Villa Petrolea by Marta Nobel, one of Ludvig’s daughters from his second marriage. Marta was a famous doctor and health care philanthropist.

‘Another project is to make a film, a Hollywood feature film, about the Nobels and Baku oil. There isn’t a script yet, but there is an outline. So much happened in the Nobels’ lives that it should not be too difficult: revolution, expropriation, the battle for oil, and so on. I think this will happen fairly soon, too.’