Pages 28-31

by Anna Oldfield Senarslan

In 2004, I received a research fellowship that would take me and my family to the Republic of Azerbaijan for two years. Like most Americans, my relatives had no idea where or what Azerbaijan is. It wasn’t long before I received a call from Aunt Helen at her retirement community.

"Look here, missy, me and the girls looked up this ’Azerbaijan’. Did you know they are 90% Shia Muslim?" It took me the next hour (and really most of the next two years) to convince her that Azerbaijanis were not terrorists, that they would not kidnap me or my six year old, and no, I would not have to wear a headscarf or "one of those Taliban things". But, considering that media coverage of conflict and war are the only images of the Islamic world most Americans see, her alarm was hardly a surprise. And while the words "Sunni" and "Islam" have become increasingly frightening, nobody even knows what a "Shia" is, except that they seem even more mysterious and dangerous than plain old "Muslims".

Recently, CNN’s Anderson Cooper 360 ran a special covering Pope Benedict’s visit to the Republic of Turkey. The series is dramatically entitled When Faiths Collide, echoing the Clash of Civilizations theory made famous by Samuel P. Huntington. The series featured Anderson Cooper discussing the Pope’s visit to Turkey with scholar Reza Aslan (whose book No god but God is one of the most readable ways to get an idea of what Islam is about). Their discussion emphasized Turkey’s importance as a secular state with a Muslim population, its stability and moderation, and its important role in bridging Europe and the Middle East. Anderson predicted the Pope would have a peaceful visit and would mend broken bridges. However, as they talked, visual images flashed by on the screen - surging crowds of angry demonstrators, shouting faces, eyes filled with rage - videos that anyone who knows the region could tell were not from Turkey at all but were taken out of context from another time and place. While the dialogue droned on, the viewer was faced with the elemental mob rage which is almost the only face given by our media to the diversity of Muslim peoples. With images like this, how can one question the assumption that faiths are colliding, that civilizations are clashing, that every bad thing in the world has happened because They are different from Us and they hate Us?

When we arrived in Azerbaijan, I myself did not know what we would encounter as an American family in a country with a majority Shia Muslim population (and minorities that include Sunni Muslims, Christians and Jews, all of whom live in peace in a country the size of Maine). All of a sudden, our world was filled with Shia Muslims looking an awful lot like ordinary people - kids, teenagers, teachers, students, musicians, taxi drivers, old folks, shop-keepers and doctors. People welcomed us and treated us with great hospitality, and soon my friends, helpers, babysitters, translators and teachers were all Shia Muslims. They did some things that I didn’t do - some fasted for Ramadan, many mourned the death of the Prophet’s grandson on the day of Ashura and most jumped over fires on the ancient holiday of Novruz. And they did a lot of things I did do - decorated a pine tree for New Year, celebrated their children’s birthdays, honoured their veterans from WWII. And just like in the US, individuals made their own choices about their faith - some people were very religious, some passively religious and some were intellectual atheists. All of them welcomed me and respected my right to my own beliefs. At Christmas and Easter, I received call after call from my Muslim friends and colleagues congratulating me on the holidays. It amazed me how welcome I was in their society, and how little the Christian/Muslim difference actually meant in a practical, day to day sense. Sometimes friends in Azerbaijan would ask me what I thought of Islam. I would answer with a metaphor I heard in a freshmen philosophy class taught by a white-bearded born-again Taoist: There is one mountain and many paths that go up it. All people are striving to get up that mountain to reach God, heaven, enlightenment, peace. Christianity is one path, Islam is another, Judaism, Buddhism, and many other faiths all provide paths for our shared human instinct to strive for the good. We are all essentially the same in our search for meaning and dignity in a confusing world, in our hope to bring justice and morality to human affairs, in our need for a way to accept the facts of human suffering and mortality, in our striving to make the world a better place for our children. No matter what our faith may be, the impulse to faith is a deeply held human commonality.

Living among Azerbaijanis, I saw the same human hopes, fears and sorrows that people face in America, and I found people’s need for faith in dark times to be no different. When I found myself with a family praying to God to help their sister stricken with cancer, I prayed with them and could anyone doubt that we were praying to the same God, despite the fact that we prayed in different languages?

Of course there are differences between Christianity and Islam, and between Sunnism and Shiism, not to mention those between the many Christianities - and there are many books and articles to turn to understand these theological issues.

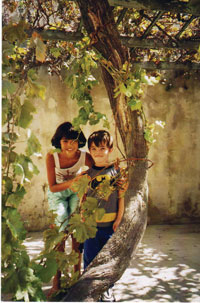

But leaving that aside, what I experienced in Azerbaijan was the basic humanity that all people share. Or as Pope Benedict said in Turkey, where despite the hype, faiths did not collide, we must increase "dialogue as a sincere exchange between friends". Back in America, showing off photos of my child playing with his Azerbaijani friends, Aunt Helen has to give in. "They sure look like nice folks," she tells her pals, with a twinkle in her eye, reassuring me that it is never too late to learn.

A. S. Oldfield is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Languages and Cultures of Asia at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

by Anna Oldfield Senarslan

In 2004, I received a research fellowship that would take me and my family to the Republic of Azerbaijan for two years. Like most Americans, my relatives had no idea where or what Azerbaijan is. It wasn’t long before I received a call from Aunt Helen at her retirement community.

"Look here, missy, me and the girls looked up this ’Azerbaijan’. Did you know they are 90% Shia Muslim?" It took me the next hour (and really most of the next two years) to convince her that Azerbaijanis were not terrorists, that they would not kidnap me or my six year old, and no, I would not have to wear a headscarf or "one of those Taliban things". But, considering that media coverage of conflict and war are the only images of the Islamic world most Americans see, her alarm was hardly a surprise. And while the words "Sunni" and "Islam" have become increasingly frightening, nobody even knows what a "Shia" is, except that they seem even more mysterious and dangerous than plain old "Muslims".

Recently, CNN’s Anderson Cooper 360 ran a special covering Pope Benedict’s visit to the Republic of Turkey. The series is dramatically entitled When Faiths Collide, echoing the Clash of Civilizations theory made famous by Samuel P. Huntington. The series featured Anderson Cooper discussing the Pope’s visit to Turkey with scholar Reza Aslan (whose book No god but God is one of the most readable ways to get an idea of what Islam is about). Their discussion emphasized Turkey’s importance as a secular state with a Muslim population, its stability and moderation, and its important role in bridging Europe and the Middle East. Anderson predicted the Pope would have a peaceful visit and would mend broken bridges. However, as they talked, visual images flashed by on the screen - surging crowds of angry demonstrators, shouting faces, eyes filled with rage - videos that anyone who knows the region could tell were not from Turkey at all but were taken out of context from another time and place. While the dialogue droned on, the viewer was faced with the elemental mob rage which is almost the only face given by our media to the diversity of Muslim peoples. With images like this, how can one question the assumption that faiths are colliding, that civilizations are clashing, that every bad thing in the world has happened because They are different from Us and they hate Us?

When we arrived in Azerbaijan, I myself did not know what we would encounter as an American family in a country with a majority Shia Muslim population (and minorities that include Sunni Muslims, Christians and Jews, all of whom live in peace in a country the size of Maine). All of a sudden, our world was filled with Shia Muslims looking an awful lot like ordinary people - kids, teenagers, teachers, students, musicians, taxi drivers, old folks, shop-keepers and doctors. People welcomed us and treated us with great hospitality, and soon my friends, helpers, babysitters, translators and teachers were all Shia Muslims. They did some things that I didn’t do - some fasted for Ramadan, many mourned the death of the Prophet’s grandson on the day of Ashura and most jumped over fires on the ancient holiday of Novruz. And they did a lot of things I did do - decorated a pine tree for New Year, celebrated their children’s birthdays, honoured their veterans from WWII. And just like in the US, individuals made their own choices about their faith - some people were very religious, some passively religious and some were intellectual atheists. All of them welcomed me and respected my right to my own beliefs. At Christmas and Easter, I received call after call from my Muslim friends and colleagues congratulating me on the holidays. It amazed me how welcome I was in their society, and how little the Christian/Muslim difference actually meant in a practical, day to day sense. Sometimes friends in Azerbaijan would ask me what I thought of Islam. I would answer with a metaphor I heard in a freshmen philosophy class taught by a white-bearded born-again Taoist: There is one mountain and many paths that go up it. All people are striving to get up that mountain to reach God, heaven, enlightenment, peace. Christianity is one path, Islam is another, Judaism, Buddhism, and many other faiths all provide paths for our shared human instinct to strive for the good. We are all essentially the same in our search for meaning and dignity in a confusing world, in our hope to bring justice and morality to human affairs, in our need for a way to accept the facts of human suffering and mortality, in our striving to make the world a better place for our children. No matter what our faith may be, the impulse to faith is a deeply held human commonality.

Living among Azerbaijanis, I saw the same human hopes, fears and sorrows that people face in America, and I found people’s need for faith in dark times to be no different. When I found myself with a family praying to God to help their sister stricken with cancer, I prayed with them and could anyone doubt that we were praying to the same God, despite the fact that we prayed in different languages?

Of course there are differences between Christianity and Islam, and between Sunnism and Shiism, not to mention those between the many Christianities - and there are many books and articles to turn to understand these theological issues.

But leaving that aside, what I experienced in Azerbaijan was the basic humanity that all people share. Or as Pope Benedict said in Turkey, where despite the hype, faiths did not collide, we must increase "dialogue as a sincere exchange between friends". Back in America, showing off photos of my child playing with his Azerbaijani friends, Aunt Helen has to give in. "They sure look like nice folks," she tells her pals, with a twinkle in her eye, reassuring me that it is never too late to learn.

A. S. Oldfield is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Languages and Cultures of Asia at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.