Pages 42-52

Pages 42-52by Dr. Hasan Quliyev & Acad. Teymur Bunyadov

Home to the Karabakh horse and several breeds of sheep, Karabakh has long been a centre of agriculture in Azerbaijan. Handicrafts such as silk and carpet weaving developed on the back of agriculture while other crafts such as jewellery making also flourished. In the first of two articles Dr Hasan Quliyev and Academician Teymur Bunyatov look in more detail at the way of life in Karabakh in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Agriculture

Three types of agriculture developed in Karabakh from ancient times to suit its diverse landscape and economic needs: stock-rearing dominated in the upland areas, where the conditions were best suited to it, arable farming in the foothills and stock-rearing, sericulture and arable farming in the plains.

Arable farming

Field-crop cultivation was the most widespread method of arable farming with cereals (wheat, barley, millet and rice) the main agricultural output. Various tools for arable farming, including ploughs pulled by oxen, were developed to work the very fertile ground and rotate the crops.

1. Simple ploughs - different types of khish or wooden plough were used with iron ploughshares (gavakhin) of varying sizes. Archaeological excavations in Azerbaijan show that wooden ploughs were used approximately in the Bronze Age, that is, in the late 2nd millennium BC. These tools were similar to those used by ancient Middle Eastern peoples (Sumerians, Babylonians and Assyrians) and around the Mediterranean.

2. Ploughs with a shaft - ulamali khish - were used mainly in the uplands (the southern flanks of the Lesser Caucasus). They were also used to prepare rice fields, that is, swampy soil.

3. The larger wooden plough or kotan was widely used in Karabakh as well as in the rest of Azerbaijan (qara kotan, aghir kotan, aghaj kotan etc.). This plough had to be pulled by eight to ten bullocks, so not all peasants could afford this type of plough. Peasants, therefore, often resorted to a combined plough (yighma kotan, ortaliq, modgam).

Since the end of the 19th century, different brands of manufactured plough were gradually introduced into Karabakh´s agriculture. With the aim of increasing crop yields and making more rational usage of land in Karabakh, different systems of land management were used, such as crop rotation (tala) and lea tillage (oran).

Irrigation was an important factor in the development of agriculture in Karabakh, especially in the lower-lying areas. First century author Strabo wrote in detail about the irrigation and fertility of land in Caucasian Albania. Today there are more than 40 settlements in Karabakh with names related to irrigation including Khindirkh, Boyuk Kahrizli (Great Springs) and Kahrizlar (Springs). The sources of water were rivers and springs (kahriz). There were also various irrigation systems: ditches (arkh), floods (basar, basma), holes (chala) and subsoil irrigation (torpaq alti)

Harvesting also took various forms in Karabakh, as in the whole of Azerbaijan: pulling up by hand (yolma), harvesting with a scythe (karanti), a sickle (oraq) or a serrated sickle (chin). After the harvest the sheaves were taken to the threshing-floor, laid in large stacks of different sizes (khara, qosha khara, kul khara) and threshed; everyone joined in the threshing (imacilik) or it was done by hired labour (muzdlu amak). The sheaves were carried on two-wheeled carts (araba), sledges (khizak) and carts of different sizes (takma araba).

Mills were located near houses. Different methods of threshing were used (with sticks - chomaq or by letting cattle walk over the scattered sheaves), but the most popular and efficient method of threshing was the use of wooden threshing boards (takval, qoshaqaval), to which flints and cast-iron teeth (charpanakh) were fastened. Horses and occasionally bullocks were harnessed to the threshing boards.

The threshed grain was kept in underground storage (chapar quyu), in large wooden tubs (kandi), large linen sacks (chuval) and leather sacks (dagarchin). Two kinds of mill (deyirman) were used to produce flour (un): the common Caucasian type of water mill and what are known as Russian (or Molokan) mills with a vertical wheel, set in motion by a steady stream of water.

Fruit and silk

Horticulture in Karabakh was practised mainly in Jabrail, Shusha and other districts. Fruit growing was developed widely. Mixed orchards were created, where apples, pears, plums, quince, apricots, peaches, cherries, date plums, cherry plums, pomegranates and other fruit grew together. Viticulture was also a main branch of agriculture in Karabakh.

In the 19th century in Karabakh, as in the rest of Azerbaijan, sericulture was divided into several separate stages: mulberry-growing (tutchuluq), silkworm-breeding (baramachiliq), silk-spinning (ipak sarima) and silk-weaving (ipaktokhuma). The silkworms raised were of different kinds: Baghdadi, Japanese, French, Italian and others. Local breeds such as Muslim barama or Turkish barama were also raised.

Sheep

The other main sphere of agriculture in Karabakh was livestock-raising. The landscape and favourable climatic conditions of Karabakh have provided large summer and winter pastures since ancient times, which has led to various kinds of stock-raising. The largest pastures in Azerbaijan as well as the whole South Caucasus were the Karabakh summer pastures. They lay in Javanshir, Shusha, Jabrail and Zangazur regions.

The main methods of livestock-raising were the use of remote pastures and the use of winter stabling coupled with summer alpine pasturing. Sheep were raised for their meat and wool and as blood stock and horses were bred. The term tarakama (a stock-rearing nomad) was widely applied to stock breeders in general but the terms elat and obachiliq were also used. In spite of the presence of pastures, attention was also paid to dry feed (alaf) and garden, long-fallow and forest hayfields (bichanak) were used.

The sheep bred in Karabakh were the local fat-tail and coarse wool breeds and they were quite different in quality and appearance. The Karabakh breeds were special amongst the dozens of sheep breeds in Azerbaijan in the 19th century. They were widespread in the Shusha, Javanshir, Jabrail and Zangazur regions and a distinctive dark-brown colour. Other breeds were also kept - the boza in Shusha and girda quyruq (literally round tail), qaradolaq, xeyerik, dimkh, shalpakh and balbas in lowland Karabakh.

Karabakh horses

Karabakh was Azerbaijan´s main horse-breeding region. The rich experience and hard work of many Azerbaijani generations created the Karabakh breed of horse. Gravestones in the Mil steppe (in the village of Peyghambar and elsewhere) from the 9th and 10th centuries have images of local golden brown Karabakh racers, known as sarilar in the Near East and Russia. They were as famous as Arabian horses and similar to Nubian horses.

Mention of the Karabakh breed of horse can be found in Russian historical literature after the Russian conquest of Azerbaijan. Historians Simonov and Marder wrote, "The Karabakh breed bears a great similarity to the noble Arabian and Persian breeds, from which the former were probably descended. I assume that the Karabakh breed is the result of the crossing of Arabian (and Persian) hoses with Turkmen ones."

Other breeds of horse were also raised in Karabakh including the maymun (which means happiness in Arabic and was called meymun in Azerbaijani), qarni yirtiq (torn stomach), almaz (uncaught) and jeyran (gazelle). These horses had coats of the colour narinj (chestnut).

Karabakh horses were in great demand among Russian officials and officers serving in the Caucasus. Russian poet Alexander Pushkin wrote: "Young Russian officials rode on Karabakh stallions." Other breeds were bred from the Karabakh horse. S.P. Urusov wrote that "The Karabakh horse has the same meaning for Asian horse-breeding as the thoroughbred racehorse for European breeding."

Horses from the herd (ilkhi) of the poet Natavan, daughter of the ruler of Karabakh, were shown in various exhibitions (at the Paris World Exhibition in 1867, in Tbilisi in 1332 and at the Moscow Agriculture Exhibition in 1896). They were often ranked first and awarded medals and diplomas.

Winter and summer quarters

The use of summer (yaylaq) and winter (qishlaq) pastures was carefully regulated in stock-rearing in Karabakh. The winter pastures were divided into separate small plots, depending on the abundance and quality of the grass. The number of sheep grazed on each plot depended on its dimensions. These plots in the Mil-Karabakh pastures were named dolu (full). The nomads´ camps in qishlaqs were called yataq or bina (literally base). Farm buildings (enclosures and shelters for stock) and buildings for the herders were situated there. The areas where the breeders stayed in summer in yaylaqs were called yurd. Karabakh shepherds stayed in different types of tent called daya, choma, mukhuri, koma alachiq and chadir. In oral folklore the terms daya and alachiq encompassed all the different types of tent.

Domestic utensils were gathered in the alachiq. They included all the essentials for yaylaq life, including household implements, beds, dishes, churns, hand mills, spinning-wheels, spindles, griddles (saj) for bread baking, different troughs, copper pots, jugs and leather bowls. Accommodation in the qishlaq was similar to the yaylaq.

Four kinds of milk were produced in Karabakh and the whole of Azerbaijan: sheep´s milk, cow´s milk, goat´s milk and buffalo´s milk. Most milk came from sheep and cows. Butter and cheese were made from the milk. Cheese was prepared from sheep´s milk (qoyun pendiri), and butter from cow´s and buffalo´s milk.

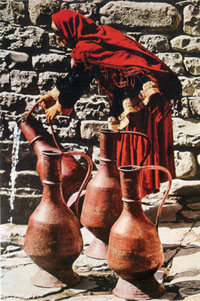

Simple vessels were used in dairy production. They can be divided into three groups: the animal kind, such as motal or animal skins and various wineskins - tajan, chalkhar, eyme and qarni and vegetable kind (barkhit, bakhachiq, chiq and others); clay dishes (nehra and other vessels); and metal, mainly copper, dishes (sarinj, qazan etc.).

Different shaped churns made from different materials were used in Karabakh dairies: clay churns (nehra), wooden churns (arkhit, alkhit) and leather churns (chalkhar, tulum, karmish).

Applied arts

Karabakh is a land of ancient artistic tradition. The richness and diversity of raw resources (wool, silk, metal, clay, wood, stone), flora and fauna and the living conditions favoured the development of handicrafts and various professions from ancient times.

The centre of craftsmanship was the cities of Shusha and Barda and the village of Lanbaran. Metal-working, dyeing, leather, wool and silk processing were all well-developed in Shusha and various craftsmen´s districts took shape.

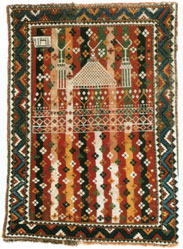

Karabakh was especially famous for its carpets, both with and without pile. The Karabakh carpet school included three groups - Karabakh, Shusha and Jabrail - which produced 33 kinds of carpet, the most famous of which were baliq (fish), lampa (lamp), buynuz (horn), qasim ushagi (Qasim´s child), talish (Talysh)

A shop in Tiflis selling Karabakh carpets. From here they were taken to Europe and Russia. 19th century

A shop in Tiflis selling Karabakh carpets. From here they were taken to Europe and Russia. 19th century Shusha was famous for the production of four kinds of silk: chatraqata - a cloth of various colours which was used for headgear, bedspreads and covers; alisha - thick pure silk cloth, which was used for clothes; and jejim which was produced in two forms - qamiyan (striped) with raised, rectilinear patterns and obagyazar (striped but without patterns). They were made from end silk (from thread from damaged cocoons), from raw spun silk mixed with silk floss and from pure silk which was especially hard-wearing. Patterns were not repeated in jejim cloth.

Sericulture was also developed in the village of Lanbaran, which became famous for its silk and wool carpets and especially its qamiyan cloth. The village of Aghjabadi produced obaqyazar cloth.

Shusha was also known for its embroidery with gold and silver thread (kulabatin tikma) and beads (khirda minchiq). Articles embroidered with gold thread were part of a bride´s dowry. The strikingly beautiful bashmaq (shoes) sewn with beads by the poet Natavan in the 19th century are of special artistic interest. They are on display at Azerbaijan´s History Museum in Baku. These bashmaq are covered with colourful beads on blue and green flower patterns against a white background.

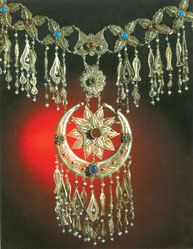

Shusha and Barda were also major jewellery centres. Karabakh jewellers used different techniques to process precious metals such as coining, stamping, browning, filigree work and encrustation. Various filigree techniques developed in Shusha and were used to produce jewellery for the head, hands and neck and men´s and women´s belts.

Leather goods were also widely used in Karabakh. A long, complex process produced shagreen (saqri), morocco Karabakh carpet, 1841, from the Klain´s collection. Germany(tumach) and juft (meshin) leather.

Material from the 19th century frequently mentions saddlery. The following quotation refers to the making of saddles (yahar) in Shusha in the 1880s: "Local saddlers prepare only pack saddles and saddles for riding with accessories." According to official figures, 89 saddlers were operating in the 1840s in Azerbaijan - in Baku, Yelizavetpol (Ganja), Nukha (Shaki), Shamakhi and Shusha.

Karabakh´s rich vegetation did not only serve as food for the population, but also provided excellent material for producing simple tools. Wood-turning developed down the centuries to our day. Wood-turning broke down into two main areas: carpentry (dulgerlik) and joinery (kharratchiliq). Specializations developed in wood-working, such as wheel-making, coopering, cart-making, wood-carving, basketry (sabat) and mat-weaving (hasir). Shusha and Javanshir regions were famed for their two-wheeled carts and wagons.

Domestic items and utensils were decorated, such as scales for dry goods (chanakh), mugs, small trunks (mujri), leaves of wall lockers, wooden frames, mirrors and pegs.

Shabaka windows also deserve special mention. They were made from small pieces of wood assembled into a lattice, with pieces of coloured glass inserted into the lattice without the use of nails. Shabaka and wooden lattices without glass were found in Shusha before its occupation by Armenian armed forces.

Dwellings

Ethnographic documents refer to various types of settlement in Karabakh: kand (village, country), bina (settlement), oba (hamlet), oymaq (small village) and yurd (stopping place, halt). Settlements in Karabakh were mainly clusters of houses, scattered farmsteads or streets of houses, depending on relief and geography. Clusters of houses were characteristic of the upland areas of Karabakh, while scattered farmsteads were found in the arable farming and horticultural area of Lower Karabakh. Villages with streets were rarer, with most of them found along country roads and river banks.

The emergence and development of different types of housing in Karabakh were directly linked to the level of socio-economic development, geography and local culture and lifestyle. Settlements in Karabakh can be divided into two types: seasonal-portable (temporary) and seasonal-non portable constructions; and permanent constructions.

Seasonal settlements came in several types and had different local names: daya, alachiq, mukhru and magar. All the summer quarters shared the same form and were made from the same materials.

Permanent winter quarters in Karabakh initially took the form of a paya, a simple one-room dwelling which was not collapsible. A paya was known by different names - paya bashi, yani achiq and oyluk.

Another type of dwelling was the chovustan or chavistan, which used to be widespread in Karabakh. This wattled dwelling is also known as turluch in anthropological literature. In lowland Karabakh the lower part of the walls were built of mud brick, but the rest of the walls and the roof were interlaced cane twigs.

Artificial caves were another popular form of dwelling in Karabakh. Artificial caves (zaga, dalma, maghara and panah) are an ancient type of human habitation. They were built with one and two chambers (bir va iki khanali). People lived there together with their livestock, but in the multi-chambered caves there were separate quarters for the stock. The caves were heated through an open fireplace. The entrance was closed either with a door of switches or a carpet without pile. Niches of different sizes, mangers, places for food storage and domestic utensils were built into the walls.

Other dwellings in Karabakh were qaradams (dam, shasha oylik, torpaq dam, ev dami). A qaradam is one of the oldest and most widespread types of national dwelling not only in Karabakh and the South Caucasus, but also in many countries of the world.

Anthropologist K.T. Karakashli has identified three categories of qaradam in the Lesser Caucasus. Qaradams had either one or more rooms and were home to large families. In all qaradams the floor was packed earth, covered with carpets without pile and in richer families mats (hasir) were laid under the carpets. A large ottoman (charpayi) was placed at one wall, where the members of the family slept. The daily utensils were kept on a wide bench. The fireplace was in the centre of the qaradam beneath a smoke hole which was also a source of light. In some qaradams a tandir or oven situated under the smoke hole was used for heating and baking. Qaradams were built of roughly processed wood, mud, mud brick and stone.

Another type of permanent dwelling in Karabakh was the bagdadi, which is considered a step closer to modern buildings. A widespread type of dwelling was the taghband. From the late 19th century a second floor was built over a taghband for habitation while the ground floor was used as a livestock-shed. The place names Taghlar and Taghavar in Mountainous Karabakh are related to taghband. Most dwellings in Karabakh had one or more rooms and one or two storeys and were square or a U shape. They had local names such as otaq, imarat and agh otaq.

The main construction materials were mud brick (chiy karpij, ayi balasi), red brick (qizil karpij), cobblestone (chay dashi), hewn stone (yonma dash), planks (takhta) and other kinds of timber, glass (shusha), iron (demir), tiles (kiramit) and limestone (ahang). Cane and reed were widely used in construction. Ordinary construction materials such as thin twigs (chubuq), felt (kecha) and wicker fences were used for seasonal and temporary dwellings.

After preparing the construction materials homeowners would invite masons (benna) to build their dwelling. According to tradition, older houses opened into a courtyard and had blank walls on the street side. From the second half of the 19th century houses began to be designed with windows and sheltered wooden balconies in the walls facing the street. A veranda or porch (eyvan) was an essential element and sometimes ran the whole length of the outer wall. Roofs had different forms, depending on the construction materials: gables (iki chatili), hipped (kulafrangi, ambalali) and flat.

Stained-glass window (or shabaka) in Shush home, from V.V.Vereshchagin´s painting Hall in Shusha, 1865

Stained-glass window (or shabaka) in Shush home, from V.V.Vereshchagin´s painting Hall in Shusha, 1865 Interiors

A characteristic feature of the interior of dwellings was the shelves and niches of different sizes (takhcha, chemokhodan and yuk yeri) and fireplaces (bukhari). The richer houses had colourful wall hangings in Shusha and shabaka - a large stained glass lattice window that took up one of the walls of the room or veranda. Niches large and small were covered with curtains (parda); the wealthy families had expensive curtains, decorated with spangles, beads and embroidery. The upper part of the curtains had a colourful fringe (parda ustu - literally the top of the curtain), while the middle section was decorated with golden embroidery (zarandaz) and the lower section with zirandaz embroidery.

In cold weather, homes were heated in different ways. Low kursu (chairs) or square stools were used for this purpose; they were placed over the tandir or oven and covered with a blanket or palaz (a kind of carpet without pile). Dwellings typically had earthen floors, but from the second half of the 19th century wooden floors came into use. Earthen and wooden floors were covered with carpets of different quality. Homes were lit with oil lamps (chiraq) with a rag wick and from the late 19th century kerosene lamps.

Traditional multi-roomed dwellings in Karabakh had guest rooms with striking, colourful decoration.

As money became more important in the second half of the 19th century and a prosperous section of Karabakh peasantry emerged, new types of dwellings appeared with high ceilings, many windows, gable roofs and a flue.

The farmstead (mulk, heyat) had a simple internal structure, consisting of a dwelling, farm buildings and a hayloft (samanliq). The whole farmstead was enclosed with stone or brick walls or fences and had a double-wing gate (ala qapi), through which a vehicle (wagon, sledge) could enter the yard. The fences had different local names depending on the construction material (hasar, chapar, tapan, basma chapar and so on). The farmstead, which was both an economic and residential space, was designed to suit its location.

About the authors: Doctor on historical sciences Hasan Quliyev was a professor, employee of the Archeology and Ethnography Institution of ANAS

Academician Teymur Bunyadov prominent Azerbaijani ethnographer-historian. He is the author of the three-volume Azerbaijan Ethnography fundamental research.

Literature

Narodi Kavkaza (Peoples of the Caucasus), Vol. 2 Moscow, 1962

Q.A. Quliyev, Ob okhotnikh orudiyakh i sistemakh zemledeliya v Azerbaydzhane (Hunting weapons and farming systems in Azerbaijan). Azerbaijani Ethnographic Collection, Issue No 2, Baku, 1965.

Strabo, Geography, Book 9, Chapter 4.

L. Simonov and I. Marder Loshadi (konskiye porodi), (Horses [Thoroughbreds]), Paris, 1895.

A.S. Pushkin, Puteshestviye v Arzerum (Journey to Erzurum), Collected Works, Volume 2, 1937.

I.I. Kalugin, Issledovaniye sovremennogo sostoyaniya zhivotnovodstva Azerbaydzhana (Research into the current state of stock-rearing in Azerbaijan), Volume 5, Baku, 1930

Georgian Central State Archive

International symposium on oriental carpets, thesis and papers, Baku, 1983.

SMOMPK, 9th issue

A.S. Vartapedov, Ocherk zhilish i kadrov Nagornogo Karabakha (Outline of dwellings and people of Mountainous Karabakh), material from a visit to Karabakh in summer 1933, AzFAN, Baku 1936.

.jpg)