Pages 80-87

by Mohbaddin Samad

A 25-year-old painter appeared in Baku in 1955. From the day he was first seen in the city, legends and myths began to form around him. This man, whom many did not know well, was, however, no stranger. In fact he was born here, to be exact, on 7 August 1930. The repression and exiles that took place later, i.e. in 1937, affected his family too. They dictated that he spend some time living in Samarkand before studying at the State Higher School of Art in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius. This was Togrul Narimanbeyov – now renowned and currently living in Paris - this People’s Painter of the USSR and of the Azerbaijani Republic, and laureate of state awards of the USSR and the Azerbaijani Republic. Today, we are talking with him.

- Togrul muellim, you and I have known each other as friends and colleagues for many years now. In 1984, I published a full study of your life and work in three volumes – in Azerbaijani, Russian and English. I have also written numerous newspaper and magazine articles and made TV and radio programmes, both in our country and abroad, at different times. However, for various reasons we have never referred openly and in detail to your family and genealogy. In 1937, your family suffered repression. I think we can talk openly about this now, can’t we?

- Certainly, in the current period of independence we can, and need to, talk openly and in detail about our family and genealogy and also about the troubles that we suffered in 1937. The only thing I know about our genealogy is that the Narimanbeyovs, whose names are pronounced with respect nowadays, were one of the wealthy families of Karabakh’s Shusha. Everyone across Karabakh knew and respected the elder of the family, Nariman bey. He had two sons, called Hasim and Amir. After completing the Yerevan gymnasium, Hasim bey taught there. Amir bey graduated from the law department of Kharkiv University. Under the Azerbaijani People’s Republic (1918-1920), he was Baku’s governor–general. Hasim bey’s son Nariman bey graduated from Moscow University’s physics and mathematics department and Kharkiv University’s law department. He worked as a defence lawyer and an educator. He joined the Musavat (Equality) party in 1917 and participated in the party’s first congress. He was elected a member of the trans-Caucasus Seim (parliament) and a member of the parliament of the Azerbaijani People’s Republic. In 1919, he held the post of Supervising Minister in the fourth cabinet of the Azerbaijani People’s Republic. In the Soviet period, he worked as a legal adviser for different organizations. He was repeatedly subjected to political and physical pressure. In the 1930s, he was arrested and sent to the well-known Solovki military prison camp, together with well-known members of the Azerbaijani Musavat party.

Yaqub Farman bey was Amir bey’s son. He was born in 1898 in the town of Shusha. He worked as chairman of the State Defence Committee under the Azerbaijani People’s Republic. In December 1919, the Azerbaijani People’s Republic sent Yaqub Farman bey to France to receive a higher education. He studied there for seven years and became an engineer. While studying in France, he married a girl called Irma who was originally from Gascony. Following their marriage, my brother Vidadi (he was an Azerbaijani People’s Painter) was born in 1927 and after him I was born in Baku in 1930.

After the Azerbaijani People’s Republic was occupied by the red empire, the people who had worked in senior posts were persecuted, some of them were killed and some exiled. This happened to my father, too. On 31 December 1937, just one day before the new year, members of the State Policy Department of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs of Azerbaijan arrested him on charges that “Yaqub Farman bey Narimanbeyov is involved in sabotage in the energy department of Baku Council” and also “for trying to separate Azerbaijan from the USSR militarily, by means of espionage, terror, sabotage etc, in Baku in late 1936”.

On 23 August 1938, a special session under the USSR People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs looked into my father’s case and sentenced him to five years “for counter-revolutionary activities”. On 11 September 1938, he was sent to a prison located in Kolyma. Our family – my mother Irma, my brother Vidadi and I - were exiled to Uzbekistan, to the ancient town of Samarkand. We faced many great difficulties during exile. These difficulties continued after my father was released from prison, too, because he was not allowed to live in Baku. He settled in Mingacevir and was involved in the construction of the State Hydroelectric Power Station there. In 1956, my father was acquitted “... because there was no corpus delicti (evidence) in his case”. After this, we gradually got back on our feet and started to live.

- As I can see, you’ve had lots of ups and downs in your life. The stigma of the “family of a public enemy” stayed with your family for a long time. This prevented you from living a normal life and receiving a normal education. In such difficult times, where did this idea of becoming a painter come from?

- I was very interested in painting from when I was very little. I liked to draw pictures showing various moods with chalk on the asphalt, walls and other places. While at elementary school, I joined a painting hobby group that operated in the city’s house of pioneers. My teachers always liked my works and always praised me. All this gave me strength and inspiration and boosted my confidence. I was convinced that I could only find myself in painting. And so my path to painting went through, first, the Azim Azimzade Baku State School of Art and then the Higher State Institute of Art in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius. I gained very valuable skills at both schools. The experienced painters who taught me made me see what a real painter and painting are, what style and manner are. It was then that I began my search in this direction. Now and again, I come across these words written by influential art critics and journalists about my work in both local and foreign media: “... Togrul Narimanbeyov is an artist with a unique style and manner”. I like these words very much, because I have sacrificed my life and my health to earn them.

Incidentally, I should say that when a painter, composer or other creative person has their own unique style and manner and differs from others, they are liked and accepted as a true artist. If they walk the way someone else does and follow them blindly, they cannot grow and take shape as an attention-grabbing artist. There have been many cases like this in the world’s art history. You know very well that some artists work according to their time, creating “tidy works” in which everything is in the right place but which do not have a unique style and although they are very famous in their time, they do not stay in people’s memories. You can ask me: why do you think Matisse, Cezanne, van Gogh, Modigliani, Picasso and Sattar Bahlulzade are still alive in people’s memories? Because they have their unique style and, I would even say, colours. This is what true original and great artists should be like.

- You spent part of your childhood in Azerbaijan, part in Uzbekistan and a large part of your youth in Lithuania. If it is not a secret – what did those places give you?

- Normally, those who have beauty around them fail to see that beauty because they are always surrounded by it. The saying goes that if you want to see the beauty of the place where you live, move a little away from there. My fate took me away from Azerbaijan for a long time. I lived in Uzbekistan and Lithuania. When I was there, Uzbekistan helped me to see and perceive Azerbaijan’s beauty while Lithuania helped me understand Azerbaijan better.

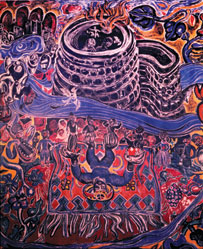

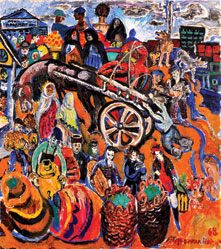

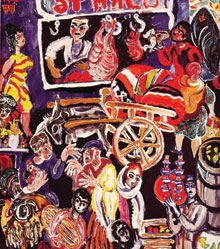

This is a truth that needs no proof: no geographical area inhabited by an artist ever fails to leave a trace. It makes its mark in the artist’s character, facial features and, finally, in his work. While I lived in Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan, I came across the finesse of the art of medieval Eastern miniature and while I lived and studied in Lithuania, I came across the hardness of the baroque style of Western architecture. Gradually, this Eastern finesse and Western hardness naturally merged in my paintings, producing modernist works of national and universal mood.

- There are artists whose impact on art cannot be felt at all. However, your impact on art caused a major fuss and real uproar in the 1950s. From the very first day, some praised and some criticized your work. Was this your lot or a trick of fate?

- There are objective reasons why such a situation developed around me at that time. One of the main reasons was that a process of revolutionary change was under way in art at the time. A wave of art called the “people of the 60s” enveloped the former Soviet area. People who arrived in the world of art on that wave had a different way of thinking to their predecessors and they worked differently. New creative streams and new creative trends appeared in the country. Some people expressed themselves in the realist trend, some in the romantic and some in the poetic or abstract, surrealist trend. And I was one of them. In my works there were elements of both the “hard style” and the “Jack of Diamonds” art society of the early 20th century.

In addition, I studied at the High School of Art in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, which was one of the Baltic countries considered to be the bearers of European culture back in the Soviet period. Although this High School of Art was socialist in form, it was global in content. The painters who taught us always recommended that we look at the world not through a limited frame but through a global prism. Because I am a graduate of this High School of Art, the points I have noted have been reflected in my work, too. Naturally, this non-traditionalism and this globalism appeared strange and incomprehensible to many. This is why at some points I was both appreciated and criticized. I never feared intelligent criticism that could benefit my work. I believed that I had done major work and people that knew about art analysed this major work scientifically and conducted polemics around it.

- Once I read an interview with the world-famous Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez. I still remember the Nobel Prize winner’s answer: “While writing ‘Autumn of the Patriarch’ I listened to almost all of Bela Bartok. You cannot imagine how surprised I was when two people I had never met were brought to interview me. They told me: “After we read your novel very closely, we decided that its structure was the same as Bartok’s Piano Concerto No 3”. I was very surprised because I thought that I had only used Bartok on a few aesthetic questions. Later on, I understood that those people were right.”

In recalling this, I mean to say that people say the same thing about some of your works. In particular, there are many people who say that your monumental wall paintings “Nagillar Alami” (World of Tales) and “Cicaklan, dogma yurdum manim” (Become a flower, my native land) are structured as fairytales and legends. Is this really so?

- I am a professional painter and a professional musician. I received a higher education in both arts and I have proven myself in both areas in practice. My friends and acquaintances who know about the visual arts and music, art experts, art critics and journalists have also said what you’re saying. Some have said that some of my works are structured like mugham and beyati music, while others say they are structured like fairytales and legends. I should say openly that when I start on a painting I never plan to paint and structure it as a fairytale, legend, mugham or beyati. All painting processes proceed naturally. Apparently, the fact that I am a serious musician, am deeply involved with it and am also very aware of Azerbaijani folklore and ethnography, emerges naturally in some of my paintings, independently of me.

I remember that there was once such talk about Gara Garayev’s symphonic works, too. He wrote music using Albanian, Vietnamese and African themes; they were called “Albanian rhapsody”, “Vietnamese suite”, and “Ildirimli Yollarla”. When they listened to these works they always said the same thing: “... Although these pieces are about the life of different nations, we can feel an Azerbaijani composer’s hand in them”.

Such things are natural in art and we should all accept them as natural.

- Earlier, we touched upon monumental wall painting. Let’s talk about this complex and difficult genre in more detail. What do you think this is this genre’s unique beauty?

- Wall painting has a very ancient history. It developed at different times in Eastern, European and Western countries. Back in the Renaissance period, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Rubens draw grand multi-themed religious paintings on church walls. These works live today too. And they will continue to live.

This sphere was once the focus of attention in Eastern countries. Special importance was attached to wall painting in Iran, Azerbaijan, Turkey and India. Back in the Middle Ages, grand wall paintings were done in shahs’ palaces and culture venues where people often gathered, based on miniatures by Soltan Mahammad, Kamaladdin Behzad and Agamirak, the greats of the Tabriz miniature school. And now these paintings have become a source of aesthetic pleasure for everyone.

I also did monumental wall paintings. It is a difficult and complex job. It is a piece of cake to work on linen. If you make a mistake, you don’t have to show it to people, or you can scour it or destroy it. But with monumental wall painting, when you make a mistake there is no way you can hide it. Either you have to destroy it all or it has to stay with the defect. For this reason, monumental wall painting needs a ready composition, like the “Sur” and “Kurd Ovsari” by composer Fikret Amirov, everything in the right place, so you can engrave it on the wall without fear or hesitation.

- You lived and worked in the USA from 1989-92, in Luxembourg from 1992-93 and in Paris since 1993. In the works you created in these places, there is one feature that attracted my attention. It seems that the atmosphere there has not affected you. While living in those countries, you still painted Azerbaijan and the irreplaceable gift of its land – the pomegranate. What do you think is the reason for this?

- People of art have needed to prove themselves, establish themselves and get themselves known since ancient times. Naturally, I have also striven to the same ends for many years. I wanted not only myself but people of the whole world to enjoy my works aesthetically. This is why I held solo exhibitions in the cities of Boston and New York while I lived in the USA, in Luxembourg when I lived there, and in the French capital’s famous “Couvent des Cordeliers” exhibition hall. These exhibitions caused a huge fuss, the main reason being my works, which were painted in a national spirit refreshed by the breeze of novelty. In the USA and European and Western countries there is major interest in art which is new to them and which are ethnic and modern. The abstract works that they come across constantly but which do not feed, or have any effect on, their spirit, exhaust them, so to speak.

Why do I paint Azerbaijan and its irreplaceable gift, the pomegranate, when I am in those countries? Because all of these things – Azerbaijan, its people, flowers, pomegranates and the colours that accompany them – are new to them and interesting. When I lived in Luxembourg, the world-famous Kyrgyz writer Chingiz Aytmatov was also there, as an ambassador. We often met and exchanged thoughts. Once, when he was at my solo exhibition, he could not hide his astonishment and said simply: “Togrul, what a perfect blood memory you have”. Naturally, he did not say that without reason. He said it because he saw the spirit of nationality and globalism in my painting. I think that regardless of their ethnicity, all people of art should be like this. Wherever they are, they are loved and accepted as artists with national memories.

- Just as van Gogh’s sunflowers and Petr Konchalovsky’s lilacs became the symbols of their work, the pomegranate has also become a symbol in yours. Gradually, you’re focusing more on pomegranates. Where does your infinite love for the pomegranate come from?

- The pomegranate is our land’s peerless gift. In our fairytales, it is portrayed as the bearer of mystery. The pomegranate is popularly regarded as a symbol of unity, prosperity and cleanliness. I view it as a carrier of the sun’s energy and of the brightness of colours. It is for this reason that I paint it lovingly into my works and have made it a symbol. I want a torrent of warm energy to flow into the souls of all people from a fruit which is the peerless bearer of the energy of the sun.

- You are known not only as a world-famous painter, but also as a singer with a beautiful voice and as an intellectual poet. Is this a hobby or simply self-expression?

- I have been singing since I was young. You have seen it for yourself – there has always been a piano in my studio. I like to hum ancient Italian and Azerbaijani folk songs, both when working on a piece and in my free time. Most of all I liked the performing schools of Jabbar Garyagdioglu, Bulbul and Italy’s musical giants Enrico Caruso, Beniamino Gigli, Mario Del Monaco and Carlo Bergonzi. Back in the Soviet period, I performed my songs on TV several times. Some people liked and praised them, and some did not like them. After Azerbaijan gained independence, I gave two concert programmes – once in Kirha (1996) and once at the Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre (1998).

I like singing very much. When I am not singing I feel uneasy and after I have sung I feel easy. As for writing poems, yes, I have written many poems. Some of them have been published in the press, and some have not been circulated. I am going to publish a book of my poems this year.

- They say that performing starts with rehearsing. Do you have the time and conditions to do this, and also an assistant?

- When I am in Baku I often rehearse at the Azerbaijani State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre. Sometimes I do it at home. My wife, Sevil khanim, helps me with this. Since Sevil khanim is a musician with a higher education, she accompanies me on the piano.

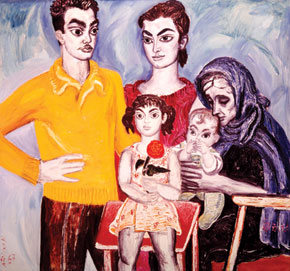

- Looking at the paintings that your son Mirtogrul Francois has drawn, I can see that he is very talented. Do you hope and believe that in the future he will be a painter and will take your place?

- He is very interested in painting. He has done some very interesting paintings. I believe in his future and am very hopeful.

- A journalist friend of mine visited the US city of Boston recently and he came across a museum-exhibition hall named after you. It would be interesting to hear your thoughts about this...

- There is a professor called Bernd Seizinger in Boston, who is a fan of my work. He works at Princeton University. He has acquired many of my works at different times. He has more than 60 now. This museum-exhibition hall which is named after me and which consists of my works, has been operating for over 10 years. He says that there is great interest in the museum and my works which are held and permanently exhibited there.

- Strange and paradoxical as it may seem, I would like to ask you something. What is your favourite holiday destination?

- You probably expect that my answer will be “I like to spend my holidays in Azerbaijan”. No, I will say quite the opposite: I am not able to take the holiday I want in Azerbaijan. Because here, the people that I come across in the street or other places have truly always inspired me and called on me to work. To be more exact, each one of them is a hero of a future work. These heroes always take my holiday away from me. They get me to draw them. I am only able to have a comfortable holiday where the people I meet are not the type I want to draw.

- There is a globalization process under way in the world currently. Views on this process vary. Some back this process from the bottom of their hearts and some are completely against it. You live and work in the USA, Germany, Luxembourg, France and other European and Western countries. And you are constantly within this process. What is your view of national cultures against this backdrop?

- This is a see-and-learn world. Countries and nations which integrate with each other and unite learn a lot from each other. These unifications give an impetus to the development of cultures too. However, similarly to genetic changes in fruit, they can also create unpleasant consequences. In some cases the fruit is no longer what it was originally. Although it is fruitful and looks attractive, the taste is not quite the same. I do not want national cultures to be like this after globalization. It is a beautiful thing when national cultures retain their roots and are in harmony with the globe.

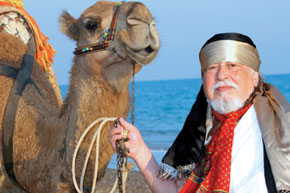

... Sometimes you can see him in Baku - in the meandering streets of the Old Town, on Istiqlal and other avenues, on the seaside promenade, and also in Paris – in the Champs-Elysees, at the Arc de Triomphe, near the Eiffel Tower, at Saint-Germain, Montparnasse, the Louvre, on the banks of the River Seine and in other places. I have noticed that nobody goes past this old man of noble appearance without giving him some attention. They give him a warm look and greet him with a smile. Some stop and, like old friends and acquaintances, ask him how he is. This man is the child of Yaqub Farman bey of Shusha and Irma khanim of Gascony, a goodwill ambassador of our cultures, the world-famous painter Togrul Narimanbeyov. As always, this incomparable artist, who has that perfect blood memory, amazes people of the world and shares his joy with his incomparably creative work.

About the author: Mohbaddin Samad’s book, titled “Togrul Narimanbeyov”, was published in 1984 in Azerbaijani, Russian and English. His popular science articles have been published in the Azerbaijani and foreign press and his programmes have been aired on TV and radio. A full-length documentary called “Togrul” is currently being filmed from his script. His next book, “Sux ranglarin taranasi” (Song of bright colours) is being prepared for publication.

by Mohbaddin Samad

A 25-year-old painter appeared in Baku in 1955. From the day he was first seen in the city, legends and myths began to form around him. This man, whom many did not know well, was, however, no stranger. In fact he was born here, to be exact, on 7 August 1930. The repression and exiles that took place later, i.e. in 1937, affected his family too. They dictated that he spend some time living in Samarkand before studying at the State Higher School of Art in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius. This was Togrul Narimanbeyov – now renowned and currently living in Paris - this People’s Painter of the USSR and of the Azerbaijani Republic, and laureate of state awards of the USSR and the Azerbaijani Republic. Today, we are talking with him.

- Togrul muellim, you and I have known each other as friends and colleagues for many years now. In 1984, I published a full study of your life and work in three volumes – in Azerbaijani, Russian and English. I have also written numerous newspaper and magazine articles and made TV and radio programmes, both in our country and abroad, at different times. However, for various reasons we have never referred openly and in detail to your family and genealogy. In 1937, your family suffered repression. I think we can talk openly about this now, can’t we?

- Certainly, in the current period of independence we can, and need to, talk openly and in detail about our family and genealogy and also about the troubles that we suffered in 1937. The only thing I know about our genealogy is that the Narimanbeyovs, whose names are pronounced with respect nowadays, were one of the wealthy families of Karabakh’s Shusha. Everyone across Karabakh knew and respected the elder of the family, Nariman bey. He had two sons, called Hasim and Amir. After completing the Yerevan gymnasium, Hasim bey taught there. Amir bey graduated from the law department of Kharkiv University. Under the Azerbaijani People’s Republic (1918-1920), he was Baku’s governor–general. Hasim bey’s son Nariman bey graduated from Moscow University’s physics and mathematics department and Kharkiv University’s law department. He worked as a defence lawyer and an educator. He joined the Musavat (Equality) party in 1917 and participated in the party’s first congress. He was elected a member of the trans-Caucasus Seim (parliament) and a member of the parliament of the Azerbaijani People’s Republic. In 1919, he held the post of Supervising Minister in the fourth cabinet of the Azerbaijani People’s Republic. In the Soviet period, he worked as a legal adviser for different organizations. He was repeatedly subjected to political and physical pressure. In the 1930s, he was arrested and sent to the well-known Solovki military prison camp, together with well-known members of the Azerbaijani Musavat party.

Yaqub Farman bey was Amir bey’s son. He was born in 1898 in the town of Shusha. He worked as chairman of the State Defence Committee under the Azerbaijani People’s Republic. In December 1919, the Azerbaijani People’s Republic sent Yaqub Farman bey to France to receive a higher education. He studied there for seven years and became an engineer. While studying in France, he married a girl called Irma who was originally from Gascony. Following their marriage, my brother Vidadi (he was an Azerbaijani People’s Painter) was born in 1927 and after him I was born in Baku in 1930.

After the Azerbaijani People’s Republic was occupied by the red empire, the people who had worked in senior posts were persecuted, some of them were killed and some exiled. This happened to my father, too. On 31 December 1937, just one day before the new year, members of the State Policy Department of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs of Azerbaijan arrested him on charges that “Yaqub Farman bey Narimanbeyov is involved in sabotage in the energy department of Baku Council” and also “for trying to separate Azerbaijan from the USSR militarily, by means of espionage, terror, sabotage etc, in Baku in late 1936”.

On 23 August 1938, a special session under the USSR People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs looked into my father’s case and sentenced him to five years “for counter-revolutionary activities”. On 11 September 1938, he was sent to a prison located in Kolyma. Our family – my mother Irma, my brother Vidadi and I - were exiled to Uzbekistan, to the ancient town of Samarkand. We faced many great difficulties during exile. These difficulties continued after my father was released from prison, too, because he was not allowed to live in Baku. He settled in Mingacevir and was involved in the construction of the State Hydroelectric Power Station there. In 1956, my father was acquitted “... because there was no corpus delicti (evidence) in his case”. After this, we gradually got back on our feet and started to live.

- As I can see, you’ve had lots of ups and downs in your life. The stigma of the “family of a public enemy” stayed with your family for a long time. This prevented you from living a normal life and receiving a normal education. In such difficult times, where did this idea of becoming a painter come from?

- I was very interested in painting from when I was very little. I liked to draw pictures showing various moods with chalk on the asphalt, walls and other places. While at elementary school, I joined a painting hobby group that operated in the city’s house of pioneers. My teachers always liked my works and always praised me. All this gave me strength and inspiration and boosted my confidence. I was convinced that I could only find myself in painting. And so my path to painting went through, first, the Azim Azimzade Baku State School of Art and then the Higher State Institute of Art in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius. I gained very valuable skills at both schools. The experienced painters who taught me made me see what a real painter and painting are, what style and manner are. It was then that I began my search in this direction. Now and again, I come across these words written by influential art critics and journalists about my work in both local and foreign media: “... Togrul Narimanbeyov is an artist with a unique style and manner”. I like these words very much, because I have sacrificed my life and my health to earn them.

Incidentally, I should say that when a painter, composer or other creative person has their own unique style and manner and differs from others, they are liked and accepted as a true artist. If they walk the way someone else does and follow them blindly, they cannot grow and take shape as an attention-grabbing artist. There have been many cases like this in the world’s art history. You know very well that some artists work according to their time, creating “tidy works” in which everything is in the right place but which do not have a unique style and although they are very famous in their time, they do not stay in people’s memories. You can ask me: why do you think Matisse, Cezanne, van Gogh, Modigliani, Picasso and Sattar Bahlulzade are still alive in people’s memories? Because they have their unique style and, I would even say, colours. This is what true original and great artists should be like.

- You spent part of your childhood in Azerbaijan, part in Uzbekistan and a large part of your youth in Lithuania. If it is not a secret – what did those places give you?

- Normally, those who have beauty around them fail to see that beauty because they are always surrounded by it. The saying goes that if you want to see the beauty of the place where you live, move a little away from there. My fate took me away from Azerbaijan for a long time. I lived in Uzbekistan and Lithuania. When I was there, Uzbekistan helped me to see and perceive Azerbaijan’s beauty while Lithuania helped me understand Azerbaijan better.

This is a truth that needs no proof: no geographical area inhabited by an artist ever fails to leave a trace. It makes its mark in the artist’s character, facial features and, finally, in his work. While I lived in Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan, I came across the finesse of the art of medieval Eastern miniature and while I lived and studied in Lithuania, I came across the hardness of the baroque style of Western architecture. Gradually, this Eastern finesse and Western hardness naturally merged in my paintings, producing modernist works of national and universal mood.

- There are artists whose impact on art cannot be felt at all. However, your impact on art caused a major fuss and real uproar in the 1950s. From the very first day, some praised and some criticized your work. Was this your lot or a trick of fate?

- There are objective reasons why such a situation developed around me at that time. One of the main reasons was that a process of revolutionary change was under way in art at the time. A wave of art called the “people of the 60s” enveloped the former Soviet area. People who arrived in the world of art on that wave had a different way of thinking to their predecessors and they worked differently. New creative streams and new creative trends appeared in the country. Some people expressed themselves in the realist trend, some in the romantic and some in the poetic or abstract, surrealist trend. And I was one of them. In my works there were elements of both the “hard style” and the “Jack of Diamonds” art society of the early 20th century.

In addition, I studied at the High School of Art in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, which was one of the Baltic countries considered to be the bearers of European culture back in the Soviet period. Although this High School of Art was socialist in form, it was global in content. The painters who taught us always recommended that we look at the world not through a limited frame but through a global prism. Because I am a graduate of this High School of Art, the points I have noted have been reflected in my work, too. Naturally, this non-traditionalism and this globalism appeared strange and incomprehensible to many. This is why at some points I was both appreciated and criticized. I never feared intelligent criticism that could benefit my work. I believed that I had done major work and people that knew about art analysed this major work scientifically and conducted polemics around it.

- Once I read an interview with the world-famous Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez. I still remember the Nobel Prize winner’s answer: “While writing ‘Autumn of the Patriarch’ I listened to almost all of Bela Bartok. You cannot imagine how surprised I was when two people I had never met were brought to interview me. They told me: “After we read your novel very closely, we decided that its structure was the same as Bartok’s Piano Concerto No 3”. I was very surprised because I thought that I had only used Bartok on a few aesthetic questions. Later on, I understood that those people were right.”

In recalling this, I mean to say that people say the same thing about some of your works. In particular, there are many people who say that your monumental wall paintings “Nagillar Alami” (World of Tales) and “Cicaklan, dogma yurdum manim” (Become a flower, my native land) are structured as fairytales and legends. Is this really so?

- I am a professional painter and a professional musician. I received a higher education in both arts and I have proven myself in both areas in practice. My friends and acquaintances who know about the visual arts and music, art experts, art critics and journalists have also said what you’re saying. Some have said that some of my works are structured like mugham and beyati music, while others say they are structured like fairytales and legends. I should say openly that when I start on a painting I never plan to paint and structure it as a fairytale, legend, mugham or beyati. All painting processes proceed naturally. Apparently, the fact that I am a serious musician, am deeply involved with it and am also very aware of Azerbaijani folklore and ethnography, emerges naturally in some of my paintings, independently of me.

I remember that there was once such talk about Gara Garayev’s symphonic works, too. He wrote music using Albanian, Vietnamese and African themes; they were called “Albanian rhapsody”, “Vietnamese suite”, and “Ildirimli Yollarla”. When they listened to these works they always said the same thing: “... Although these pieces are about the life of different nations, we can feel an Azerbaijani composer’s hand in them”.

Such things are natural in art and we should all accept them as natural.

- Earlier, we touched upon monumental wall painting. Let’s talk about this complex and difficult genre in more detail. What do you think this is this genre’s unique beauty?

- Wall painting has a very ancient history. It developed at different times in Eastern, European and Western countries. Back in the Renaissance period, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Rubens draw grand multi-themed religious paintings on church walls. These works live today too. And they will continue to live.

This sphere was once the focus of attention in Eastern countries. Special importance was attached to wall painting in Iran, Azerbaijan, Turkey and India. Back in the Middle Ages, grand wall paintings were done in shahs’ palaces and culture venues where people often gathered, based on miniatures by Soltan Mahammad, Kamaladdin Behzad and Agamirak, the greats of the Tabriz miniature school. And now these paintings have become a source of aesthetic pleasure for everyone.

I also did monumental wall paintings. It is a difficult and complex job. It is a piece of cake to work on linen. If you make a mistake, you don’t have to show it to people, or you can scour it or destroy it. But with monumental wall painting, when you make a mistake there is no way you can hide it. Either you have to destroy it all or it has to stay with the defect. For this reason, monumental wall painting needs a ready composition, like the “Sur” and “Kurd Ovsari” by composer Fikret Amirov, everything in the right place, so you can engrave it on the wall without fear or hesitation.

- You lived and worked in the USA from 1989-92, in Luxembourg from 1992-93 and in Paris since 1993. In the works you created in these places, there is one feature that attracted my attention. It seems that the atmosphere there has not affected you. While living in those countries, you still painted Azerbaijan and the irreplaceable gift of its land – the pomegranate. What do you think is the reason for this?

- People of art have needed to prove themselves, establish themselves and get themselves known since ancient times. Naturally, I have also striven to the same ends for many years. I wanted not only myself but people of the whole world to enjoy my works aesthetically. This is why I held solo exhibitions in the cities of Boston and New York while I lived in the USA, in Luxembourg when I lived there, and in the French capital’s famous “Couvent des Cordeliers” exhibition hall. These exhibitions caused a huge fuss, the main reason being my works, which were painted in a national spirit refreshed by the breeze of novelty. In the USA and European and Western countries there is major interest in art which is new to them and which are ethnic and modern. The abstract works that they come across constantly but which do not feed, or have any effect on, their spirit, exhaust them, so to speak.

Why do I paint Azerbaijan and its irreplaceable gift, the pomegranate, when I am in those countries? Because all of these things – Azerbaijan, its people, flowers, pomegranates and the colours that accompany them – are new to them and interesting. When I lived in Luxembourg, the world-famous Kyrgyz writer Chingiz Aytmatov was also there, as an ambassador. We often met and exchanged thoughts. Once, when he was at my solo exhibition, he could not hide his astonishment and said simply: “Togrul, what a perfect blood memory you have”. Naturally, he did not say that without reason. He said it because he saw the spirit of nationality and globalism in my painting. I think that regardless of their ethnicity, all people of art should be like this. Wherever they are, they are loved and accepted as artists with national memories.

- Just as van Gogh’s sunflowers and Petr Konchalovsky’s lilacs became the symbols of their work, the pomegranate has also become a symbol in yours. Gradually, you’re focusing more on pomegranates. Where does your infinite love for the pomegranate come from?

- The pomegranate is our land’s peerless gift. In our fairytales, it is portrayed as the bearer of mystery. The pomegranate is popularly regarded as a symbol of unity, prosperity and cleanliness. I view it as a carrier of the sun’s energy and of the brightness of colours. It is for this reason that I paint it lovingly into my works and have made it a symbol. I want a torrent of warm energy to flow into the souls of all people from a fruit which is the peerless bearer of the energy of the sun.

- You are known not only as a world-famous painter, but also as a singer with a beautiful voice and as an intellectual poet. Is this a hobby or simply self-expression?

- I have been singing since I was young. You have seen it for yourself – there has always been a piano in my studio. I like to hum ancient Italian and Azerbaijani folk songs, both when working on a piece and in my free time. Most of all I liked the performing schools of Jabbar Garyagdioglu, Bulbul and Italy’s musical giants Enrico Caruso, Beniamino Gigli, Mario Del Monaco and Carlo Bergonzi. Back in the Soviet period, I performed my songs on TV several times. Some people liked and praised them, and some did not like them. After Azerbaijan gained independence, I gave two concert programmes – once in Kirha (1996) and once at the Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre (1998).

I like singing very much. When I am not singing I feel uneasy and after I have sung I feel easy. As for writing poems, yes, I have written many poems. Some of them have been published in the press, and some have not been circulated. I am going to publish a book of my poems this year.

- They say that performing starts with rehearsing. Do you have the time and conditions to do this, and also an assistant?

- When I am in Baku I often rehearse at the Azerbaijani State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre. Sometimes I do it at home. My wife, Sevil khanim, helps me with this. Since Sevil khanim is a musician with a higher education, she accompanies me on the piano.

- Looking at the paintings that your son Mirtogrul Francois has drawn, I can see that he is very talented. Do you hope and believe that in the future he will be a painter and will take your place?

- He is very interested in painting. He has done some very interesting paintings. I believe in his future and am very hopeful.

- A journalist friend of mine visited the US city of Boston recently and he came across a museum-exhibition hall named after you. It would be interesting to hear your thoughts about this...

- There is a professor called Bernd Seizinger in Boston, who is a fan of my work. He works at Princeton University. He has acquired many of my works at different times. He has more than 60 now. This museum-exhibition hall which is named after me and which consists of my works, has been operating for over 10 years. He says that there is great interest in the museum and my works which are held and permanently exhibited there.

- Strange and paradoxical as it may seem, I would like to ask you something. What is your favourite holiday destination?

- You probably expect that my answer will be “I like to spend my holidays in Azerbaijan”. No, I will say quite the opposite: I am not able to take the holiday I want in Azerbaijan. Because here, the people that I come across in the street or other places have truly always inspired me and called on me to work. To be more exact, each one of them is a hero of a future work. These heroes always take my holiday away from me. They get me to draw them. I am only able to have a comfortable holiday where the people I meet are not the type I want to draw.

- There is a globalization process under way in the world currently. Views on this process vary. Some back this process from the bottom of their hearts and some are completely against it. You live and work in the USA, Germany, Luxembourg, France and other European and Western countries. And you are constantly within this process. What is your view of national cultures against this backdrop?

- This is a see-and-learn world. Countries and nations which integrate with each other and unite learn a lot from each other. These unifications give an impetus to the development of cultures too. However, similarly to genetic changes in fruit, they can also create unpleasant consequences. In some cases the fruit is no longer what it was originally. Although it is fruitful and looks attractive, the taste is not quite the same. I do not want national cultures to be like this after globalization. It is a beautiful thing when national cultures retain their roots and are in harmony with the globe.

... Sometimes you can see him in Baku - in the meandering streets of the Old Town, on Istiqlal and other avenues, on the seaside promenade, and also in Paris – in the Champs-Elysees, at the Arc de Triomphe, near the Eiffel Tower, at Saint-Germain, Montparnasse, the Louvre, on the banks of the River Seine and in other places. I have noticed that nobody goes past this old man of noble appearance without giving him some attention. They give him a warm look and greet him with a smile. Some stop and, like old friends and acquaintances, ask him how he is. This man is the child of Yaqub Farman bey of Shusha and Irma khanim of Gascony, a goodwill ambassador of our cultures, the world-famous painter Togrul Narimanbeyov. As always, this incomparable artist, who has that perfect blood memory, amazes people of the world and shares his joy with his incomparably creative work.

About the author: Mohbaddin Samad’s book, titled “Togrul Narimanbeyov”, was published in 1984 in Azerbaijani, Russian and English. His popular science articles have been published in the Azerbaijani and foreign press and his programmes have been aired on TV and radio. A full-length documentary called “Togrul” is currently being filmed from his script. His next book, “Sux ranglarin taranasi” (Song of bright colours) is being prepared for publication.