Pages 64-70

by Gazanfar Rajabli

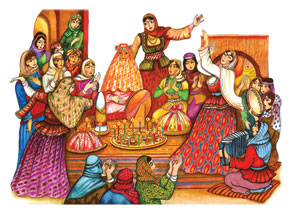

The wedding is one of the most beautiful and richest embodiments of the spiritual values of Azerbaijan. Here the ‘wedding’ actually means the last stage in the modern process of marriage, the final celebration with a dinner-dance. Our ancestors, however, understood ‘wedding’ to mean any ‘festivity’, a time for eating, drinking, playing and dancing. The festive meaning of wedding is illustrated in our oldest surviving literature, in the epic ‘The Book of Dede Korkut’. There is said in the epos: “Once a year, Bayandur, the khan of the khans organised a wedding (toy-duyun) and invited the Oghuz beys too”.

In Azerbaijan the wedding consisted of several stages: approval of the bride (matchmaking), proposing marriage, engagement (betrothal) and a wedding party.

Approval of the bride

In the approval of a bride, along with her beauty, stature, innocence, skilful housekeeping, efficiency, intellect, courtesy and other qualities, special consideration was also given to the personality of her mother. There is a popular proverb: “look at the edge when you buy coarse calico, look at the mother when you marry a daughter”.

In former times, the mother, aunts or sisters of a young man of marriageable age were on the lookout for a suitable girl at weddings, funerals, holidays, street festivities and springs (sources of water – ed.). In some cases the mother or sister went to the prospective bride’s home. In this case the girl would feign ignorance of their mission and serve tea as for any guest.

In former times, the girl was not asked for her opinion about a possible marriage. Later, when girls were asked for their opinion they would answer “my parents know”. In noble families the girls usually were asked and would be listened to.

In noble circles, as well as the customs of ‘seeing’ and ‘approving a bride’, there would be ‘seeing a groom’, ‘approving a groom’ and also a testing ceremony. In ‘The Book of Dede Korkut’, the ruler of Trabzon, before wedding his daughter Seljan to Ganturali, put him to the test. The testing ceremony was also an opportunity to ‘see the groom’. When Ganturali went into the square to fight with wild animals, Seljan watched him from the summerhouse and fell in love with him.

The stage of proposing marriage that followed the ‘approval of the girl’ was a very important event in the life of an Azerbaijani family.

Elchi - the envoy

Seeking the advice of relatives and elders before proposing marriage has long been the custom. A matchmaker (elchi-envoy) exercised special authority over people. The person sent to propose marriage had to be talented and a good communicator. The matchmaker was expected to proceed directly to the essence, using choice words to substantiate their own thoughts.

It was usual for three or four men, and one or two women, to propose the marriage. These matchmakers were usually a grandfather, the father and uncles of the groom. The groom’s mother and aunts made up the women’s contingent.

According to custom and tradition, matchmakers were received respectfully by the girl’s family, as they were considered to be envoys from Allah. Even if they did not consent to the marriage, the bride’s family had to respect the matchmakers, receiving and seeing them off with dignity.

Notwithstanding the fact that a sufra would be laid out (a tablecloth usually set on the floor or on a low table for a meal) for the visitors, the groom’s matchmakers did not reach out for food until they received a positive answer. Only after the bride’s consent was given, would the matchmakers put sugar into their tea, saying “Allah blesses them” (Allah mubarek elesin) and sweeten their mouths. Then a pilaf was brought in. The mother of the groom called the fiancée into the room where the women were sitting and put an engagement ring onto her finger for confidence, covering her head with a scarf. In some regions of Azerbaijan this ceremony was called the ‘affirmation’.

The news of the proposal was met with joy by relatives, friends and neighbours of the girl, her parents were congratulated. Since the girl’s “consent” had been given, she and the young man were considered to be “betrothed”.

When the matchmakers were given a negative answer, it was done in an inoffensive manner so that the families would not become enemies. This tradition is described in the great Azerbaijani poet, Fuzuli’s ‘Leyli and Mejnun’. Leyli’s father turns down Mejnun’s father in a gentle manner, with respect for his pride and dignity. Leyli’s father displays humanity for Mejnun’s father and does not dash his hopes. He pledges with the words: “Take measures to cure your son” and “when he is healthy they will marry”.

We know from the romantic epics that a bride’s father would observe the rules of propriety towards matchmakers and, instead of rejecting them, would find another way - perhaps laying down difficult conditions for a groom.

Proposing marriage

In most regions of Azerbaijan, the ceremony to propose marriage and the engagement ceremony have been mixed. As a ring and a shawl were usually taken to an engagement, this ceremony was also called ‘taking a ring and shawl’ in Baku, Tabriz, Lenkeran and other regions. In ‘The book of Dede Korkut’ the ceremony of engagement and proposing marriage (the ceremony of shirni ichmek – to drink sweet tea,) is called ‘a small wedding’. The epic says: “Yalinjig, the son of the liar, proposed marriage, celebrated a small wedding and fixed the date of the big wedding”.

On the engagement day ‘nishan khonchasi’ (engagement trays usually filled with sweets and presents) were taken by the groom’s family to the girl’s home. Depending on the family’s means, along with a ring and a headscarf, earrings, a bracelet, a necklace, a locket and other jewellery, 1 or 2 pieces of fabric to make clothes and various sweetmeats were also among the presents. Besides the mother and sisters of the prospective groom, his nearest relatives would also prepare khonchas (trays) and go to the girl’s home. The trays were not returned empty. The girl’s family returned a special khoncha called the ‘top of the sugar loaf’ (gand bashi) to the groom’s home on the same trays. Usually the top part of a sugar loaf was broken and put on the tray.

After the engagement, the couple were officially considered betrothed. From the day of betrothal, the fiancée had to half cover her face with a headscarf in the presence of the groom’s relatives and the groom had to avoid meeting the bride’s close relatives.

In order to let them get accustomed to each other after the engagement, the betrothed were allowed to see each other with the consent of both families. This custom, called ‘adakhlibazlig’ (a meeting of the betrothed pair) was nicely described in the musical comedy “Not This One, then That One” by the great composer, U. Hajibeyov.

During the holidays at “Novruz”, “Ramadan” and the Moslem Feast of Sacrifice (commemorating Ibrahim/Ismayil - Abraham/Isaac – ed.), a groom’s family usually sent festive presents for the bride. In the Moslem Feast of Sacrifice, a ram with a silk scarf tied around its neck and henna-dye on its head was sent. According to custom, the groom’s family bought clothes for the betrothed girl while she was living in her father’s home.

Wedding festivities

After the official engagement, the groom’s family began preparing for the big wedding. All kinds of clothes and jewellery were bought for the bride. The bride’s family also started to make dowry preparations. In rich families, the bride’s dowry would have been assembled throughout her life. Close to the wedding day, relatives and neighbours assembled to prepare the bride’s bedding and arrange the dowry.

According to the folk custom, before the wedding party, the bride was a guest of relatives and friends in turn. At the end of the visit she would be given blankets, mattresses, pillows, a nazbalish (a large, soft pillow), cushions, carpets, copper pans and other kitchenware. These were all added to her dowry.

The first wedding ceremony was held in the bride’s home. The groom’s family covered the expenses. Several rams with red cloths tied around their necks or with henna-dyed heads and various foodstuffs were also provided.

One of the wedding traditions was called ‘paltarkesdi’ (a ritual ceremony to tailor and display dresses for the bride (an old Azerbaijani tradition). Throughout paltarkesdi day there was music and dancing in the groom’s home. In the afternoon all the clothes were put into a chest, sweetmeats and food were put into baskets and everything was taken to the bride’s home to musical accompaniment. The women stayed there playing and dancing, enjoying themselves. Then the groom’s mother took the clothes from the chest, put them onto trays (khonchas) and led other women into the party, carrying the khonchas and dancing. One woman would show off the clothes on the trays to all who participated in the party, declaring: “Allah bless her! Who saw saw, let others see!” After showing the clothes brought for the bride they were returned onto the trays. All the women, starting with the groom’s mother, put money onto the clothes. This was given to the one who had displayed them. A widow was usually chosen for this duty, to support her with the money collected. After putting the clothes into the chest, the groom’s mother locked it and gave the key to the bride’s mother.

A sew-in

In the 1940’s, the ethnographer, Rakhshanda Babayeva, described a ‘paltarkesdi’ party in her book, “Wedding customs of the city of Guba”: “The groom’s mother sent a message to the bride’s home and warned them that they were coming next day for the paltarkesdi ceremony. As soon as the bride’s mother got the message she started preparations and invited some close women relatives. On the appointed day the groom’s mother arrived with around ten close relatives and neighbours. The visitors sat on cushions spread across the carpets and began talking. A large tablecloth was brought and laid in the centre of the room. Someone from the bride’s family put the clothes chest into the middle and began to take the fabrics and lay them out on the tablecloth. Then a dress and a blouse belonging to the bride were brought and, using them as a guide some dresses were sized and cut from the lengths of fabric. After tailoring the clothes, everybody wished: “Allah bless them! May they have sons and daughters and grow old together”. All the clothes and fabrics were placed into the chest. Then the tablecloth was laid for a meal and a woman with an aftafa-leyen (aftafa - a jug with a long spout used for ablutions, leyen – basin) helped the women, starting with the groom’s mother, to wash their hands”. For guests invited to the paltarkesdi ceremony, a chicken pilaf, spiced with saffron, sabzigovurma (fried greens and meat), chighirtma (a dish cooked from lamb or chicken dressed with egg), aubergine dolma (a dish cooked from aubergines, tomatoes and sweet peppers filled with minced and spiced meat) and nar govurma (roast meat dressed with pomegranates) were cooked in rich families. Less well-off families served pilaf cooked in milk and dressed with raisins, dried persimmon, smoked omul or chub. Poorer families offered bozbash (stew with peas and some spices) or dolma (vine leaves stuffed with minced lamb) and dovgha (a dish made from liquid yogurt and finely chopped herbs). After eating, the women drank tea with lemon or jam and left the party blessing the betrothed. After the ‘paltarkesdi’ stage the big wedding, the last stage of the wedding ceremonies began.

According to sources, in ancient times, Azerbaijani weddings lasted 40 days and 40 nights. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the big wedding in rich families lasted 7 days and 7 nights, sometimes 3 days, but usually 1 day, in average or poor families. 2-3 days before the wedding, a messenger was sent round the houses dispensing sweets and inviting people to the wedding.

A few days before the wedding, bread and yukha (bread baked with thinly rolled dough) were baked and stored in the groom’s home. The day before the wedding close relatives and neighbours gathered in the groom’s home to help. Animals were slaughtered and meat was stored. A few men chopped the meat, the women minced it for dolma and lule kebab (meat chopped, formed into a tube shape and roasted on spits). The offal of the animals killed was roasted and served out the helpers. After dinner, duties were assigned: erectors of the wedding tent, managers of the wedding, cooks, waiters, tea makers, distributors of tea, also people responsible for greeting guests, bringing musicians, delivering the bride and others.

Music, sport.... and henna

A marquee for the wedding ceremony was erected in the groom’s courtyard or other appropriate place. This was the ‘toykhana’ (wedding house). In all regions of Azerbaijan the wedding began with the sound of the gara zurna (an oriental wind instrument). As soon as the zurna players arrived at the toykhana, they walked to a high position and started to play music announcing the start of the wedding. The population of the village, hearing the sounds of the zurna from some distance, flowed towards the toykhana. Wedding guests wore new, clean clothes. A wedding was a celebration for the whole village.

If wedding ceremonies were the core of the customs and traditions of family life in Azerbaijan, then the decoration was the music. Rich families invited several music bands consisting of a khanende (a singer who usually sings mughams), some sazende (saz players) and ashugs (Caucasian folk poets and singers) to the wedding. Weddings in poorer families featured players of the zurna, balaban (wind instruments), naghara (an oriental drum) and gaval (a tambourine). Irrespective of social origin and financial status of the family, it was impossible to imagine a wedding in Garabagh without a khanende, or in Shirvan and other regions without ashugs.

When ashugs related the epics, the whole population of a village listened. Ashugs, or ozans, adorned Azerbaijani weddings even in ancient times. During all Oghuz (a Turkic tribe) weddings the ozan sat in prime position. ‘The Book of Dede Korkut’ tells of Oghuz wedding ceremonies, mentioning the musical instruments zurna and naghara, as well as the folk dance ‘yelletme’(yalli) (waving) and ashugs “who played a gopuz (an old Azerbaijani stringed instrument) and sang songs”.

It is traditional to give presents to wedding messengers, musicians, singers, khanendes and ashugs. The folk epics tell us that ashugs lived by people’s support.

The master of ceremonies of the wedding was the ‘toybeyi’ (usually a man). His word was law; everybody had to obey him. The toybeyi managed the festivities with the aid of his assistants.

In rural wedding ceremonies, various sport competitions, games and entertainments were organized. The young men demonstrated their skills in horse races. A silky head-dress was tied around the neck of the winning horse or his owner was given a shirt. Some competed at wrestling and others took part in tests of strength, or their shooting skills. In ‘The Book of Dede Korkut’: “Mayar Goykun’s ring was the target. Beyrak shot through the ring with a single arrow and broke it”.

In former times, in some regions of Azerbaijan, the groom’s and the bride’s weddings were celebrated at the same time. The musicians at the bride’s wedding were all women. The bride was adorned and sat at the head of the table. In the Gazakh region, two khonchas (trays) filled with fruits, charaz (nuts, fried peas and dried fruits) and sweetmeats and ‘a shakh – tree’ (a dry branch decorated with fruits and sweets) were brought by the bridesmaids and placed before the bride. The female singers sang bayati (folk quatrains) and the girls danced.

One custom was the ‘khinayakhdi’ (all the girls and women dyed their hair and decorated their hands with henna). A few days before the wedding, the groom’s family brought a ram tied with a red ribbon and food. As evening approached, the women gathered in the bride’s home. The groom’s mother, sisters, close female relatives and neighbours prepared a khoncha and went to the bride’s house for the ‘khinayakhdi’ ceremony. Besides henna for the bride, two decorated candles, some sugar, tea, sweetmeats and fruit, there was a pair of shoes on the khoncha. Everybody in the party played and danced till midnight. After dinner, the girls dyed each other’s hands and feet with henna, accompanied by song. This was the last wedding ceremony in the bride’s home.

For her the dowry, for him the bathhouse

It was followed by the elaborate procedure of seeing the bride off to the house of the bridegroom. On this day, preparations for the wedding meal began in the morning. In the bride’s home a list was made of the bride’s dowry. Representatives of both families worked on the list. Alongside the akhund (an Islamic spiritual authority) and the mullah, were the local elders. First on the list was the Koran, then a prayer mat and a ‘mohur’ (a stone on which to rest the head while praying). One person from each family witnessed the dowry list. The signed list was submitted to the bride’s father and he in turn gave it to his wife for safekeeping.

After listing the dowry the registration of the marriage began. The marriage fee was entered on the certificate of marriage. According to shariah law, in case a man wanted to divorce his wife he had to pay her this fee. In most cases, in order to strengthen the marriage bond and to make divorce difficult, the fee indicated was quite substantial. Apart from the groom and the bride, the marriage certificate was signed by witnesses, one person from each side, as well as by an akhund or a gazi (a confessor), and sealed. After the marriage registration, the bride’s dowry was carried to the groom’s home and the bride’s room was decorated. That evening the groom, together with his attendants and peers went to the ‘beylik hamami’ (a bath-house ceremony organised for the groom). A special ‘bey khonchasi’ (a tray filled with things for the groom) for the bath-house ceremony was sent from the bride’s home. It would include a silk shirt, skull-caps, socks, silk handkerchiefs and other presents. After the bath-house ceremony, the groom put on the silk shirt and socks, a skull-cap and put one of the handkerchiefs into his pocket. The other presents were given to his attendants. The custom of the bride’s family presenting a silk shirt to the groom was an ancient one in Azerbaijan. ‘The Book of Dede Korkut’: “Beyrek received a red marriage kaftan from the bride. He put the kaftan on.”

When the groom returned from the bath-house ceremony a meal was served. After the dinner, the young people went to fetch the bride. They lit torches and marched towards the bride’s house accompanied by music. They fired guns and let off firecrackers, cheering on the way. The adorning of the bride was finished by this time. A brother or a cousin of the groom was invited inside to tie the bride’s waist. He tied a red silk sash or ribbon around the bride’s waist, over the veil, pronouncing the following:

You are my mother, you are my sister,

You are perfect happiness!

We are waiting for seven sons

And a girl with your beauty!

Then the bride’s father took her arm and walked her three times around the lamp. When the bride was leaving the room she had to break a glass or a ceramic plate in order not to take misfortune to her husband’s home. She was led under the holy “Koran” at the doorway. Her father, or one of uncles, stopped her at the threshold. Someone from the groom’s family had to give the certificate of marriage to the bride’s mother for safekeeping.

The bridal procession

In cities, the bride was taken away by phaeton. The bride’s ‘yenga’ (a woman accompanying the bride to the house of the groom) who sat in the phaeton usually carried a parcel filled with bread and sweets. A yenga of the groom usually held a lit lamp in her hand. A boy who sat next to the phaeton driver held ‘a fate mirror’ of the bride in his hand. The phaeton carrying the bride had to move slowly to allow followers on foot to keep pace with it. The bride’s procession was escorted by young people carrying torches. In rural areas the bride was taken by a horse-drawn vehicle or on horseback. The bride’s horse was covered with a red cloth. In low-lying lands the bride was carried by a Bactrian camel. The camel was decorated and carried a palanquin whose low borders were lined with bells. The elder brother (or father, or uncle) of the groom rode at the head of the procession. The young men or boys repeatedly stopped the procession, barring the way with a rope. The groom’s family would clear the way by giving them gifts or money. Thus the bridal procession eventually reached the groom’s home.

The bride was taken down from the phaeton or horse and approached the home. The groom’s mother or sister waited for her at the threshold and scattered sweets, candies and coins over her head. These were picked up by the children. In most cases a ram was sacrificed for her. In some regions, when the bride was approaching the door of the house, tongs, a spit, a horseshoe or other things made of iron were dropped at her feet - to make her place in her husband’s home as strong as iron. The bride was preceded into the house by her lamp, fate mirror and parcel of bread.

When she entered the room, some honey, sherbet, flour or dough was brought to her on a tray. The bride had to dip her finger into it and rub it onto the upper door frame. Then she had to go under the frame and, when she entered the room, she had to trample and break a china or ceramic plate with her foot.

According to custom, when the bride entered her room, her mother-in-law and father-in-law had to come and promise her a valued present called a ‘dizdayaghi’ (literally – diz – knee, dayaq – support; in rural areas this present consisted of piece of land or a milch cow (or other animal), in cities it would be jewellery or another expensive gift) and let her take a seat. When the bride sat down, a 3-4 year-old-boy was placed on her lap and a wish was made for her to have boys and girls. The bride had to put a skull-cap on the boy’s head. Then the girls and women gathered around the bride and started the entertainment: playing, dancing and singing.

The groom had not sat in the wedding marquee during the first days of the wedding. On the final evening, after the bride’s arrival, the groom was carried into the marquee accompanied by music, and sat in the specially arranged place with his attendants. The tray full of fruit, charaz (nuts, fried peas and dried fruits) and sweetmeats was laid in front of him.

At the end of the wedding there was acclamation of the groom. The ashug or khanende praised the groom and invited his parents, friends and acquaintances to give him presents. Then his mother, sisters and brothers and other relatives gathered around him dancing and singing. Later they congratulated him and left. His attendants accompanied him from the tent to the “gardak” (literally a curtain hung before the nuptial bed).

Her new family

Three days later there was the ceremony of “uzechikhdi” (the appearance of the bride before her husband’s parents after the wedding). In most places this ceremony was called “uchgun” (three days). During “uchgun” the groom’s mother cooked a meal and invited close relatives and neighbours for “gelin gordu” (literally – to meet the bride). With the guests assembled, the mother-in-law called the bride. The visitors gave her presents. The ceremony of “uzechikhdi” brought the bride into the life of her new family; she became an equal member.

The wedding ceremony that founded the Azerbaijani family has been improved and enriched through the years and centuries and has preserved its importance and splendour to our times.

About the author: Professor Gazanfar Rajabli is a leading scientist at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan and a Doctor of Philosophy in historical science. He researches into the ethnography of Azerbaijan and is the author of the “Wedding” section in the three-volume “Ethnography of Azerbaijan” (Baku, 2007)

by Gazanfar Rajabli

The wedding is one of the most beautiful and richest embodiments of the spiritual values of Azerbaijan. Here the ‘wedding’ actually means the last stage in the modern process of marriage, the final celebration with a dinner-dance. Our ancestors, however, understood ‘wedding’ to mean any ‘festivity’, a time for eating, drinking, playing and dancing. The festive meaning of wedding is illustrated in our oldest surviving literature, in the epic ‘The Book of Dede Korkut’. There is said in the epos: “Once a year, Bayandur, the khan of the khans organised a wedding (toy-duyun) and invited the Oghuz beys too”.

In Azerbaijan the wedding consisted of several stages: approval of the bride (matchmaking), proposing marriage, engagement (betrothal) and a wedding party.

Approval of the bride

In the approval of a bride, along with her beauty, stature, innocence, skilful housekeeping, efficiency, intellect, courtesy and other qualities, special consideration was also given to the personality of her mother. There is a popular proverb: “look at the edge when you buy coarse calico, look at the mother when you marry a daughter”.

In former times, the mother, aunts or sisters of a young man of marriageable age were on the lookout for a suitable girl at weddings, funerals, holidays, street festivities and springs (sources of water – ed.). In some cases the mother or sister went to the prospective bride’s home. In this case the girl would feign ignorance of their mission and serve tea as for any guest.

In former times, the girl was not asked for her opinion about a possible marriage. Later, when girls were asked for their opinion they would answer “my parents know”. In noble families the girls usually were asked and would be listened to.

In noble circles, as well as the customs of ‘seeing’ and ‘approving a bride’, there would be ‘seeing a groom’, ‘approving a groom’ and also a testing ceremony. In ‘The Book of Dede Korkut’, the ruler of Trabzon, before wedding his daughter Seljan to Ganturali, put him to the test. The testing ceremony was also an opportunity to ‘see the groom’. When Ganturali went into the square to fight with wild animals, Seljan watched him from the summerhouse and fell in love with him.

The stage of proposing marriage that followed the ‘approval of the girl’ was a very important event in the life of an Azerbaijani family.

Elchi - the envoy

Seeking the advice of relatives and elders before proposing marriage has long been the custom. A matchmaker (elchi-envoy) exercised special authority over people. The person sent to propose marriage had to be talented and a good communicator. The matchmaker was expected to proceed directly to the essence, using choice words to substantiate their own thoughts.

It was usual for three or four men, and one or two women, to propose the marriage. These matchmakers were usually a grandfather, the father and uncles of the groom. The groom’s mother and aunts made up the women’s contingent.

According to custom and tradition, matchmakers were received respectfully by the girl’s family, as they were considered to be envoys from Allah. Even if they did not consent to the marriage, the bride’s family had to respect the matchmakers, receiving and seeing them off with dignity.

Notwithstanding the fact that a sufra would be laid out (a tablecloth usually set on the floor or on a low table for a meal) for the visitors, the groom’s matchmakers did not reach out for food until they received a positive answer. Only after the bride’s consent was given, would the matchmakers put sugar into their tea, saying “Allah blesses them” (Allah mubarek elesin) and sweeten their mouths. Then a pilaf was brought in. The mother of the groom called the fiancée into the room where the women were sitting and put an engagement ring onto her finger for confidence, covering her head with a scarf. In some regions of Azerbaijan this ceremony was called the ‘affirmation’.

The news of the proposal was met with joy by relatives, friends and neighbours of the girl, her parents were congratulated. Since the girl’s “consent” had been given, she and the young man were considered to be “betrothed”.

When the matchmakers were given a negative answer, it was done in an inoffensive manner so that the families would not become enemies. This tradition is described in the great Azerbaijani poet, Fuzuli’s ‘Leyli and Mejnun’. Leyli’s father turns down Mejnun’s father in a gentle manner, with respect for his pride and dignity. Leyli’s father displays humanity for Mejnun’s father and does not dash his hopes. He pledges with the words: “Take measures to cure your son” and “when he is healthy they will marry”.

We know from the romantic epics that a bride’s father would observe the rules of propriety towards matchmakers and, instead of rejecting them, would find another way - perhaps laying down difficult conditions for a groom.

Proposing marriage

In most regions of Azerbaijan, the ceremony to propose marriage and the engagement ceremony have been mixed. As a ring and a shawl were usually taken to an engagement, this ceremony was also called ‘taking a ring and shawl’ in Baku, Tabriz, Lenkeran and other regions. In ‘The book of Dede Korkut’ the ceremony of engagement and proposing marriage (the ceremony of shirni ichmek – to drink sweet tea,) is called ‘a small wedding’. The epic says: “Yalinjig, the son of the liar, proposed marriage, celebrated a small wedding and fixed the date of the big wedding”.

On the engagement day ‘nishan khonchasi’ (engagement trays usually filled with sweets and presents) were taken by the groom’s family to the girl’s home. Depending on the family’s means, along with a ring and a headscarf, earrings, a bracelet, a necklace, a locket and other jewellery, 1 or 2 pieces of fabric to make clothes and various sweetmeats were also among the presents. Besides the mother and sisters of the prospective groom, his nearest relatives would also prepare khonchas (trays) and go to the girl’s home. The trays were not returned empty. The girl’s family returned a special khoncha called the ‘top of the sugar loaf’ (gand bashi) to the groom’s home on the same trays. Usually the top part of a sugar loaf was broken and put on the tray.

After the engagement, the couple were officially considered betrothed. From the day of betrothal, the fiancée had to half cover her face with a headscarf in the presence of the groom’s relatives and the groom had to avoid meeting the bride’s close relatives.

In order to let them get accustomed to each other after the engagement, the betrothed were allowed to see each other with the consent of both families. This custom, called ‘adakhlibazlig’ (a meeting of the betrothed pair) was nicely described in the musical comedy “Not This One, then That One” by the great composer, U. Hajibeyov.

During the holidays at “Novruz”, “Ramadan” and the Moslem Feast of Sacrifice (commemorating Ibrahim/Ismayil - Abraham/Isaac – ed.), a groom’s family usually sent festive presents for the bride. In the Moslem Feast of Sacrifice, a ram with a silk scarf tied around its neck and henna-dye on its head was sent. According to custom, the groom’s family bought clothes for the betrothed girl while she was living in her father’s home.

Wedding festivities

After the official engagement, the groom’s family began preparing for the big wedding. All kinds of clothes and jewellery were bought for the bride. The bride’s family also started to make dowry preparations. In rich families, the bride’s dowry would have been assembled throughout her life. Close to the wedding day, relatives and neighbours assembled to prepare the bride’s bedding and arrange the dowry.

According to the folk custom, before the wedding party, the bride was a guest of relatives and friends in turn. At the end of the visit she would be given blankets, mattresses, pillows, a nazbalish (a large, soft pillow), cushions, carpets, copper pans and other kitchenware. These were all added to her dowry.

The first wedding ceremony was held in the bride’s home. The groom’s family covered the expenses. Several rams with red cloths tied around their necks or with henna-dyed heads and various foodstuffs were also provided.

One of the wedding traditions was called ‘paltarkesdi’ (a ritual ceremony to tailor and display dresses for the bride (an old Azerbaijani tradition). Throughout paltarkesdi day there was music and dancing in the groom’s home. In the afternoon all the clothes were put into a chest, sweetmeats and food were put into baskets and everything was taken to the bride’s home to musical accompaniment. The women stayed there playing and dancing, enjoying themselves. Then the groom’s mother took the clothes from the chest, put them onto trays (khonchas) and led other women into the party, carrying the khonchas and dancing. One woman would show off the clothes on the trays to all who participated in the party, declaring: “Allah bless her! Who saw saw, let others see!” After showing the clothes brought for the bride they were returned onto the trays. All the women, starting with the groom’s mother, put money onto the clothes. This was given to the one who had displayed them. A widow was usually chosen for this duty, to support her with the money collected. After putting the clothes into the chest, the groom’s mother locked it and gave the key to the bride’s mother.

A sew-in

In the 1940’s, the ethnographer, Rakhshanda Babayeva, described a ‘paltarkesdi’ party in her book, “Wedding customs of the city of Guba”: “The groom’s mother sent a message to the bride’s home and warned them that they were coming next day for the paltarkesdi ceremony. As soon as the bride’s mother got the message she started preparations and invited some close women relatives. On the appointed day the groom’s mother arrived with around ten close relatives and neighbours. The visitors sat on cushions spread across the carpets and began talking. A large tablecloth was brought and laid in the centre of the room. Someone from the bride’s family put the clothes chest into the middle and began to take the fabrics and lay them out on the tablecloth. Then a dress and a blouse belonging to the bride were brought and, using them as a guide some dresses were sized and cut from the lengths of fabric. After tailoring the clothes, everybody wished: “Allah bless them! May they have sons and daughters and grow old together”. All the clothes and fabrics were placed into the chest. Then the tablecloth was laid for a meal and a woman with an aftafa-leyen (aftafa - a jug with a long spout used for ablutions, leyen – basin) helped the women, starting with the groom’s mother, to wash their hands”. For guests invited to the paltarkesdi ceremony, a chicken pilaf, spiced with saffron, sabzigovurma (fried greens and meat), chighirtma (a dish cooked from lamb or chicken dressed with egg), aubergine dolma (a dish cooked from aubergines, tomatoes and sweet peppers filled with minced and spiced meat) and nar govurma (roast meat dressed with pomegranates) were cooked in rich families. Less well-off families served pilaf cooked in milk and dressed with raisins, dried persimmon, smoked omul or chub. Poorer families offered bozbash (stew with peas and some spices) or dolma (vine leaves stuffed with minced lamb) and dovgha (a dish made from liquid yogurt and finely chopped herbs). After eating, the women drank tea with lemon or jam and left the party blessing the betrothed. After the ‘paltarkesdi’ stage the big wedding, the last stage of the wedding ceremonies began.

According to sources, in ancient times, Azerbaijani weddings lasted 40 days and 40 nights. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the big wedding in rich families lasted 7 days and 7 nights, sometimes 3 days, but usually 1 day, in average or poor families. 2-3 days before the wedding, a messenger was sent round the houses dispensing sweets and inviting people to the wedding.

A few days before the wedding, bread and yukha (bread baked with thinly rolled dough) were baked and stored in the groom’s home. The day before the wedding close relatives and neighbours gathered in the groom’s home to help. Animals were slaughtered and meat was stored. A few men chopped the meat, the women minced it for dolma and lule kebab (meat chopped, formed into a tube shape and roasted on spits). The offal of the animals killed was roasted and served out the helpers. After dinner, duties were assigned: erectors of the wedding tent, managers of the wedding, cooks, waiters, tea makers, distributors of tea, also people responsible for greeting guests, bringing musicians, delivering the bride and others.

Music, sport.... and henna

A marquee for the wedding ceremony was erected in the groom’s courtyard or other appropriate place. This was the ‘toykhana’ (wedding house). In all regions of Azerbaijan the wedding began with the sound of the gara zurna (an oriental wind instrument). As soon as the zurna players arrived at the toykhana, they walked to a high position and started to play music announcing the start of the wedding. The population of the village, hearing the sounds of the zurna from some distance, flowed towards the toykhana. Wedding guests wore new, clean clothes. A wedding was a celebration for the whole village.

If wedding ceremonies were the core of the customs and traditions of family life in Azerbaijan, then the decoration was the music. Rich families invited several music bands consisting of a khanende (a singer who usually sings mughams), some sazende (saz players) and ashugs (Caucasian folk poets and singers) to the wedding. Weddings in poorer families featured players of the zurna, balaban (wind instruments), naghara (an oriental drum) and gaval (a tambourine). Irrespective of social origin and financial status of the family, it was impossible to imagine a wedding in Garabagh without a khanende, or in Shirvan and other regions without ashugs.

When ashugs related the epics, the whole population of a village listened. Ashugs, or ozans, adorned Azerbaijani weddings even in ancient times. During all Oghuz (a Turkic tribe) weddings the ozan sat in prime position. ‘The Book of Dede Korkut’ tells of Oghuz wedding ceremonies, mentioning the musical instruments zurna and naghara, as well as the folk dance ‘yelletme’(yalli) (waving) and ashugs “who played a gopuz (an old Azerbaijani stringed instrument) and sang songs”.

It is traditional to give presents to wedding messengers, musicians, singers, khanendes and ashugs. The folk epics tell us that ashugs lived by people’s support.

The master of ceremonies of the wedding was the ‘toybeyi’ (usually a man). His word was law; everybody had to obey him. The toybeyi managed the festivities with the aid of his assistants.

In rural wedding ceremonies, various sport competitions, games and entertainments were organized. The young men demonstrated their skills in horse races. A silky head-dress was tied around the neck of the winning horse or his owner was given a shirt. Some competed at wrestling and others took part in tests of strength, or their shooting skills. In ‘The Book of Dede Korkut’: “Mayar Goykun’s ring was the target. Beyrak shot through the ring with a single arrow and broke it”.

In former times, in some regions of Azerbaijan, the groom’s and the bride’s weddings were celebrated at the same time. The musicians at the bride’s wedding were all women. The bride was adorned and sat at the head of the table. In the Gazakh region, two khonchas (trays) filled with fruits, charaz (nuts, fried peas and dried fruits) and sweetmeats and ‘a shakh – tree’ (a dry branch decorated with fruits and sweets) were brought by the bridesmaids and placed before the bride. The female singers sang bayati (folk quatrains) and the girls danced.

One custom was the ‘khinayakhdi’ (all the girls and women dyed their hair and decorated their hands with henna). A few days before the wedding, the groom’s family brought a ram tied with a red ribbon and food. As evening approached, the women gathered in the bride’s home. The groom’s mother, sisters, close female relatives and neighbours prepared a khoncha and went to the bride’s house for the ‘khinayakhdi’ ceremony. Besides henna for the bride, two decorated candles, some sugar, tea, sweetmeats and fruit, there was a pair of shoes on the khoncha. Everybody in the party played and danced till midnight. After dinner, the girls dyed each other’s hands and feet with henna, accompanied by song. This was the last wedding ceremony in the bride’s home.

For her the dowry, for him the bathhouse

It was followed by the elaborate procedure of seeing the bride off to the house of the bridegroom. On this day, preparations for the wedding meal began in the morning. In the bride’s home a list was made of the bride’s dowry. Representatives of both families worked on the list. Alongside the akhund (an Islamic spiritual authority) and the mullah, were the local elders. First on the list was the Koran, then a prayer mat and a ‘mohur’ (a stone on which to rest the head while praying). One person from each family witnessed the dowry list. The signed list was submitted to the bride’s father and he in turn gave it to his wife for safekeeping.

After listing the dowry the registration of the marriage began. The marriage fee was entered on the certificate of marriage. According to shariah law, in case a man wanted to divorce his wife he had to pay her this fee. In most cases, in order to strengthen the marriage bond and to make divorce difficult, the fee indicated was quite substantial. Apart from the groom and the bride, the marriage certificate was signed by witnesses, one person from each side, as well as by an akhund or a gazi (a confessor), and sealed. After the marriage registration, the bride’s dowry was carried to the groom’s home and the bride’s room was decorated. That evening the groom, together with his attendants and peers went to the ‘beylik hamami’ (a bath-house ceremony organised for the groom). A special ‘bey khonchasi’ (a tray filled with things for the groom) for the bath-house ceremony was sent from the bride’s home. It would include a silk shirt, skull-caps, socks, silk handkerchiefs and other presents. After the bath-house ceremony, the groom put on the silk shirt and socks, a skull-cap and put one of the handkerchiefs into his pocket. The other presents were given to his attendants. The custom of the bride’s family presenting a silk shirt to the groom was an ancient one in Azerbaijan. ‘The Book of Dede Korkut’: “Beyrek received a red marriage kaftan from the bride. He put the kaftan on.”

When the groom returned from the bath-house ceremony a meal was served. After the dinner, the young people went to fetch the bride. They lit torches and marched towards the bride’s house accompanied by music. They fired guns and let off firecrackers, cheering on the way. The adorning of the bride was finished by this time. A brother or a cousin of the groom was invited inside to tie the bride’s waist. He tied a red silk sash or ribbon around the bride’s waist, over the veil, pronouncing the following:

You are my mother, you are my sister,

You are perfect happiness!

We are waiting for seven sons

And a girl with your beauty!

Then the bride’s father took her arm and walked her three times around the lamp. When the bride was leaving the room she had to break a glass or a ceramic plate in order not to take misfortune to her husband’s home. She was led under the holy “Koran” at the doorway. Her father, or one of uncles, stopped her at the threshold. Someone from the groom’s family had to give the certificate of marriage to the bride’s mother for safekeeping.

The bridal procession

In cities, the bride was taken away by phaeton. The bride’s ‘yenga’ (a woman accompanying the bride to the house of the groom) who sat in the phaeton usually carried a parcel filled with bread and sweets. A yenga of the groom usually held a lit lamp in her hand. A boy who sat next to the phaeton driver held ‘a fate mirror’ of the bride in his hand. The phaeton carrying the bride had to move slowly to allow followers on foot to keep pace with it. The bride’s procession was escorted by young people carrying torches. In rural areas the bride was taken by a horse-drawn vehicle or on horseback. The bride’s horse was covered with a red cloth. In low-lying lands the bride was carried by a Bactrian camel. The camel was decorated and carried a palanquin whose low borders were lined with bells. The elder brother (or father, or uncle) of the groom rode at the head of the procession. The young men or boys repeatedly stopped the procession, barring the way with a rope. The groom’s family would clear the way by giving them gifts or money. Thus the bridal procession eventually reached the groom’s home.

The bride was taken down from the phaeton or horse and approached the home. The groom’s mother or sister waited for her at the threshold and scattered sweets, candies and coins over her head. These were picked up by the children. In most cases a ram was sacrificed for her. In some regions, when the bride was approaching the door of the house, tongs, a spit, a horseshoe or other things made of iron were dropped at her feet - to make her place in her husband’s home as strong as iron. The bride was preceded into the house by her lamp, fate mirror and parcel of bread.

When she entered the room, some honey, sherbet, flour or dough was brought to her on a tray. The bride had to dip her finger into it and rub it onto the upper door frame. Then she had to go under the frame and, when she entered the room, she had to trample and break a china or ceramic plate with her foot.

According to custom, when the bride entered her room, her mother-in-law and father-in-law had to come and promise her a valued present called a ‘dizdayaghi’ (literally – diz – knee, dayaq – support; in rural areas this present consisted of piece of land or a milch cow (or other animal), in cities it would be jewellery or another expensive gift) and let her take a seat. When the bride sat down, a 3-4 year-old-boy was placed on her lap and a wish was made for her to have boys and girls. The bride had to put a skull-cap on the boy’s head. Then the girls and women gathered around the bride and started the entertainment: playing, dancing and singing.

The groom had not sat in the wedding marquee during the first days of the wedding. On the final evening, after the bride’s arrival, the groom was carried into the marquee accompanied by music, and sat in the specially arranged place with his attendants. The tray full of fruit, charaz (nuts, fried peas and dried fruits) and sweetmeats was laid in front of him.

At the end of the wedding there was acclamation of the groom. The ashug or khanende praised the groom and invited his parents, friends and acquaintances to give him presents. Then his mother, sisters and brothers and other relatives gathered around him dancing and singing. Later they congratulated him and left. His attendants accompanied him from the tent to the “gardak” (literally a curtain hung before the nuptial bed).

Her new family

Three days later there was the ceremony of “uzechikhdi” (the appearance of the bride before her husband’s parents after the wedding). In most places this ceremony was called “uchgun” (three days). During “uchgun” the groom’s mother cooked a meal and invited close relatives and neighbours for “gelin gordu” (literally – to meet the bride). With the guests assembled, the mother-in-law called the bride. The visitors gave her presents. The ceremony of “uzechikhdi” brought the bride into the life of her new family; she became an equal member.

The wedding ceremony that founded the Azerbaijani family has been improved and enriched through the years and centuries and has preserved its importance and splendour to our times.

About the author: Professor Gazanfar Rajabli is a leading scientist at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan and a Doctor of Philosophy in historical science. He researches into the ethnography of Azerbaijan and is the author of the “Wedding” section in the three-volume “Ethnography of Azerbaijan” (Baku, 2007)

.jpg)