Pages 92-95

by Ian Peart & Saadat Ibrahimova

Few artists have easy lives, especially those in countries emerging from troubled times; their people, and governments, are naturally more concerned with bread than pictures – oil for engines more urgent than oil for canvas. Luckily for us, artists are necessarily blessed with imagination and usually create ways around the problems.

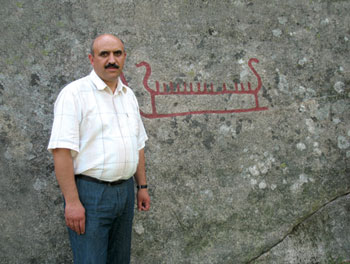

Yusif Mirza is a case in point: an artist of many talents, who is energetic in both extending and promoting his work and is always on the watch for new opportunities. Follow many an expat up the metal steps to his studio opposite the Russian Drama Theatre, on Baku’s Khagani Street, and you find yourself in a multitude of imagined worlds.

“I have awakened a thousand years of memories”

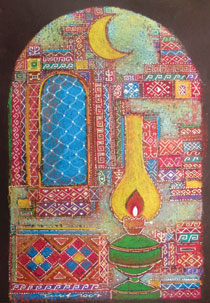

.... was the understated title of an exhibition in 2007. Here were memories of Lachin – his native village, now cut off and depopulated by hostile occupation. The personal memories take on different forms in his paintings: the soft light of an oil lamp glimmering warmly across an interior life patterned with books and carpets (‘Memory’ Xatire); a sparse (Lachin) village landscape whose red-roofs pulse with the life he once knew there.

But Mirza’s folk memories also carry recollections of a much more distant past: the 12,000 year old cave paintings (petroglyphs) of Gobustan, or the 12th century church at Kish, near Sheki.

This is no fossilised nostalgia, the patterns and petroglyphs are reworked to convey connections with the present, the future, even the distant, and there are broader views of Azerbaijan’s development and culture. Yusif Mirza’s depictions of its capital city may be combined with Gobustan motifs and they invariably carry references to the different religions that have made their mark on this religiously tolerant, predominantly Muslim nation. (‘Song about Baku’, Bakı haqqında mahnı, ‘Old Baku’)

The ancients of this land worshipped the elements (earth, air, water and, especially given the subterranean hydrocarbons, fire) and some of the earliest Christian communities were established here, epitomised by the Alban, later Armenian, church. Their temples of worship join the Islamic minarets to convey the historical atmosphere and acceptance evoked in Yusif’s Baku cityscapes.

Connections

These interests and experiments have established the most unexpected contacts. The great Norwegian scientist and adventurer Thor Heyerdahl was also intrigued by the Gobustan petroglyphs – in particular the apparent depictions of early boats which bear a remarkable resemblance to similar carvings in Norway. His reading of the 13th century ‘Edda’ stories by Snorri Sturluson led him to believe that the Vikings may have originated in this region and sailed to Scandinavia via the Volga. Of course, the adventurer ended up meeting the artist for whom the Gobustan boat motif has been so iconic.

Yusif’s Norway connections have strengthened since that meeting. A CD of music featuring Azerbaijani musicians with the well-known Norwegian ‘Skruk’ choir is contaqins one of his ‘Memory’ paintings. He has had exhibitions in Norway – during which he took the opportunity to visit the Norwegian boat petroglyphs (Norvecde and Gobustan picture?). And his tribute painting to Thor Heyerdahl was presented to the Kon-Tiki museum in Oslo.

In fact Mirza’s search for inspiration recognises few boundaries; he began a recent workshop for schoolchildren by referring them to the light in the paintings of British ‘pre-impressionist’ JMW Turner and told them, “I look at the old masters, take something and make it Azerbaijani.”

This light also exerts its influence in the cityscapes and we can see the beginnings of another experiment in ‘In a white shadow’ (Bir bəyaz kölgə) – here stylised Gobustan figures are brought into a townscape haunted by the Greek-Italian Surrealist Giorgio de Chirico.

To the future

Inspiration from the traditions of Azerbaijan’s past and the cultures of other countries do not divert the engaging and enthusiastic Yusif Mirza from his concern for the future. Thus the students mentioned earlier were the lucky recipients of a class he was invited to give at The International School of Azerbaijan (TISA). He also teaches regularly at Boarding School #3 in the Absheron peninsula settlement of Mardakan (in cooperation with the Norwegian Humanitarian Enterprise).

“It is important for children to know about art and to draw”, he said, explaining to the multinational TISA class that they were lucky to be children – a great artist like Picasso tried all his life to draw like a child. It was clear his charges were itching to get their hands on some markers and Yusif soon sparked them into action by demonstrating with a few lines how easy it was to produce a satisfying mouse or an ancient Gobustan family around the sacred hearth.

As they drew they also wanted to find out more about his life and art:

“What’s your favourite picture?”

- ‘I like them all, if I don’t like something, I can’t paint it.’

“What made you start painting?”

- ‘The great beauty of nature around my home in Lachin’.

“What is your most famous picture?”

- ‘I think the one with ships and fire is the most popular’.

“That one would take me hours! Did you really paint all these pictures?” (there were about 30 displayed around the room).

The frenzied production of the next half hour gave birth to many variations on the themes, followed by demands for the artist’s autograph – so, if a youthful agent offers you a signed original of Yusif Mirza’s ‘Mouse with a Tattoo’, (mouse picture) you are hereby warned to check its authenticity before parting with any money...

Lachin roots

Mirza’s own childhood was spent in Lachin, in west Azerbaijan. He was the first in his family to show a talent for art; his drawing and painting were encouraged but he had no specialist training. In fact, after finishing school, he headed for the capital to study at the Pedagogical Institute and train to be a teacher. Five years later, he returned to his roots, but after a short period in the classroom, he was drawn to the Lachin National Theatre to work as a set designer.

In the search for full-time employment he moved back to Baku and found work as a book illustrator. The late 1980s were a difficult time as the Soviet Union began to crumble and Armenia attacked Azerbaijan. Yusif began to carry supplies and medicines to his family, who were affected by the fighting. Eventually, in 1992, his family and friends had to flee their homeland and join him in Baku – not all of them made it, commemorated, perhaps, in the gravestones above those red roofs in ‘Lachin landscape with red-roofed houses’. (Lacin,qirmizi damli)

Apart from the obvious visual impact on his paintings of memory and those events, he became more convinced of the importance of the arts in education – he believes that greater support for the arts would also create more imaginative responses to the political and economic problems of the day.

Meanwhile the artist himself continues to experiment. A holiday (with these writers) in the northern resort of Nabran allowed us to watch his art flourish in a different direction as naturalistic landscapes in watercolour flowed from his brush (Nabran Akverellerindan, house in trees).

Yusif Mirza has expressed himself in paint, pencil and pastel, on stone, in clay and even in words. He is an artist who absorbs, reflects and transforms, but who always remembers where he first came into the light.

It’s snowing in Lachin

In memory of my father and mother, who died in the same year - Yusif Mirza

You hear it...

it’s snowing in Lachin,

Cleanest white, purest white,

Soft.

Snowing in Lachin,

white flowers,

white petals

White butterflies

waft, wafting through the air,

Lightly, one by one

nestling into the earth.

Snowing in Lachin

everywhere silent,

Everywhere white,

Hochaz Rock

Merkiz Mountain

Lost in greying mist.

It’s snowing in Lachin,

You hear it...

You are listening...

You remember...

Why do you cry...

Why do you cry...

December 2000-2003

(Trans.SI & IP)

Yusif Mirza’s Baku studio is on 4 Khagani Street, opposite the Russian Drama Theatre – look for the ‘Artist’s Studio’ sign, go through the arch and up the metal steps on the left. Mob. (994 50) 3478543. You can see more of his works at http://www.museumcenter.az/art_gallery,344/lang,en/

by Ian Peart & Saadat Ibrahimova

Few artists have easy lives, especially those in countries emerging from troubled times; their people, and governments, are naturally more concerned with bread than pictures – oil for engines more urgent than oil for canvas. Luckily for us, artists are necessarily blessed with imagination and usually create ways around the problems.

Yusif Mirza is a case in point: an artist of many talents, who is energetic in both extending and promoting his work and is always on the watch for new opportunities. Follow many an expat up the metal steps to his studio opposite the Russian Drama Theatre, on Baku’s Khagani Street, and you find yourself in a multitude of imagined worlds.

“I have awakened a thousand years of memories”

.... was the understated title of an exhibition in 2007. Here were memories of Lachin – his native village, now cut off and depopulated by hostile occupation. The personal memories take on different forms in his paintings: the soft light of an oil lamp glimmering warmly across an interior life patterned with books and carpets (‘Memory’ Xatire); a sparse (Lachin) village landscape whose red-roofs pulse with the life he once knew there.

But Mirza’s folk memories also carry recollections of a much more distant past: the 12,000 year old cave paintings (petroglyphs) of Gobustan, or the 12th century church at Kish, near Sheki.

This is no fossilised nostalgia, the patterns and petroglyphs are reworked to convey connections with the present, the future, even the distant, and there are broader views of Azerbaijan’s development and culture. Yusif Mirza’s depictions of its capital city may be combined with Gobustan motifs and they invariably carry references to the different religions that have made their mark on this religiously tolerant, predominantly Muslim nation. (‘Song about Baku’, Bakı haqqında mahnı, ‘Old Baku’)

The ancients of this land worshipped the elements (earth, air, water and, especially given the subterranean hydrocarbons, fire) and some of the earliest Christian communities were established here, epitomised by the Alban, later Armenian, church. Their temples of worship join the Islamic minarets to convey the historical atmosphere and acceptance evoked in Yusif’s Baku cityscapes.

Connections

These interests and experiments have established the most unexpected contacts. The great Norwegian scientist and adventurer Thor Heyerdahl was also intrigued by the Gobustan petroglyphs – in particular the apparent depictions of early boats which bear a remarkable resemblance to similar carvings in Norway. His reading of the 13th century ‘Edda’ stories by Snorri Sturluson led him to believe that the Vikings may have originated in this region and sailed to Scandinavia via the Volga. Of course, the adventurer ended up meeting the artist for whom the Gobustan boat motif has been so iconic.

Yusif’s Norway connections have strengthened since that meeting. A CD of music featuring Azerbaijani musicians with the well-known Norwegian ‘Skruk’ choir is contaqins one of his ‘Memory’ paintings. He has had exhibitions in Norway – during which he took the opportunity to visit the Norwegian boat petroglyphs (Norvecde and Gobustan picture?). And his tribute painting to Thor Heyerdahl was presented to the Kon-Tiki museum in Oslo.

In fact Mirza’s search for inspiration recognises few boundaries; he began a recent workshop for schoolchildren by referring them to the light in the paintings of British ‘pre-impressionist’ JMW Turner and told them, “I look at the old masters, take something and make it Azerbaijani.”

This light also exerts its influence in the cityscapes and we can see the beginnings of another experiment in ‘In a white shadow’ (Bir bəyaz kölgə) – here stylised Gobustan figures are brought into a townscape haunted by the Greek-Italian Surrealist Giorgio de Chirico.

To the future

Inspiration from the traditions of Azerbaijan’s past and the cultures of other countries do not divert the engaging and enthusiastic Yusif Mirza from his concern for the future. Thus the students mentioned earlier were the lucky recipients of a class he was invited to give at The International School of Azerbaijan (TISA). He also teaches regularly at Boarding School #3 in the Absheron peninsula settlement of Mardakan (in cooperation with the Norwegian Humanitarian Enterprise).

“It is important for children to know about art and to draw”, he said, explaining to the multinational TISA class that they were lucky to be children – a great artist like Picasso tried all his life to draw like a child. It was clear his charges were itching to get their hands on some markers and Yusif soon sparked them into action by demonstrating with a few lines how easy it was to produce a satisfying mouse or an ancient Gobustan family around the sacred hearth.

As they drew they also wanted to find out more about his life and art:

“What’s your favourite picture?”

- ‘I like them all, if I don’t like something, I can’t paint it.’

“What made you start painting?”

- ‘The great beauty of nature around my home in Lachin’.

“What is your most famous picture?”

- ‘I think the one with ships and fire is the most popular’.

“That one would take me hours! Did you really paint all these pictures?” (there were about 30 displayed around the room).

The frenzied production of the next half hour gave birth to many variations on the themes, followed by demands for the artist’s autograph – so, if a youthful agent offers you a signed original of Yusif Mirza’s ‘Mouse with a Tattoo’, (mouse picture) you are hereby warned to check its authenticity before parting with any money...

Lachin roots

Mirza’s own childhood was spent in Lachin, in west Azerbaijan. He was the first in his family to show a talent for art; his drawing and painting were encouraged but he had no specialist training. In fact, after finishing school, he headed for the capital to study at the Pedagogical Institute and train to be a teacher. Five years later, he returned to his roots, but after a short period in the classroom, he was drawn to the Lachin National Theatre to work as a set designer.

In the search for full-time employment he moved back to Baku and found work as a book illustrator. The late 1980s were a difficult time as the Soviet Union began to crumble and Armenia attacked Azerbaijan. Yusif began to carry supplies and medicines to his family, who were affected by the fighting. Eventually, in 1992, his family and friends had to flee their homeland and join him in Baku – not all of them made it, commemorated, perhaps, in the gravestones above those red roofs in ‘Lachin landscape with red-roofed houses’. (Lacin,qirmizi damli)

Apart from the obvious visual impact on his paintings of memory and those events, he became more convinced of the importance of the arts in education – he believes that greater support for the arts would also create more imaginative responses to the political and economic problems of the day.

Meanwhile the artist himself continues to experiment. A holiday (with these writers) in the northern resort of Nabran allowed us to watch his art flourish in a different direction as naturalistic landscapes in watercolour flowed from his brush (Nabran Akverellerindan, house in trees).

Yusif Mirza has expressed himself in paint, pencil and pastel, on stone, in clay and even in words. He is an artist who absorbs, reflects and transforms, but who always remembers where he first came into the light.

It’s snowing in Lachin

In memory of my father and mother, who died in the same year - Yusif Mirza

You hear it...

it’s snowing in Lachin,

Cleanest white, purest white,

Soft.

Snowing in Lachin,

white flowers,

white petals

White butterflies

waft, wafting through the air,

Lightly, one by one

nestling into the earth.

Snowing in Lachin

everywhere silent,

Everywhere white,

Hochaz Rock

Merkiz Mountain

Lost in greying mist.

It’s snowing in Lachin,

You hear it...

You are listening...

You remember...

Why do you cry...

Why do you cry...

December 2000-2003

(Trans.SI & IP)

Yusif Mirza’s Baku studio is on 4 Khagani Street, opposite the Russian Drama Theatre – look for the ‘Artist’s Studio’ sign, go through the arch and up the metal steps on the left. Mob. (994 50) 3478543. You can see more of his works at http://www.museumcenter.az/art_gallery,344/lang,en/