Pages 70-73

by Suleyman Aliyarli

Arastun Mehtiyev

The Nobel family’s presence in Baku dates from the early 1870s when the oil industry was ¬released from the fetters of the lease system and gradually quickened its development. In fact Robert Nobel was sent to the mountainous areas of Azerbaijan to search for walnut trees for the manufacture ¬of rifle butts in ¬their Izhevsk rifle factory¬. The trip was not successful, however, as the government decided to use cheap and easily produced birch wood instead¬. While in Baku, Robert became familiar with the situation in the oil industry and understood that there were good prospects for profit there. In 1873, after arriving back in St. Petersburg, he convinced his brother Ludvig to invest in Baku’s oil industry¬ and, ¬in 1875, he obtained some oil producing land in Sabunchi district -and set up drilling operations. Robert Nobel also bought a small kerosene factory for ¬25 thousand roubles and began refining oil.

Innovation

The Nobel Brothers realised quite quickly the necessity of a radical transformation ¬ and modernisation ¬of the oil business. Their name became associated with a range of innovations ¬in the industry.

In the 1870s oil was delivered from the fields to the refineries and the coast, as well as to other cities, in barrels; this made industrialists dependent on the carters and barrel manufacturers and was a brake on development and expansion¬. Ludvig Nobel suggested that the producers jointly construct a pipeline connecting oilfields to the refineries and seaports. His proposal was not supported and so, in 1878, he built a pipeline using his company’s own resources. This was soon followed by others and within a year there were already three oil pipelines. Ludvig also developed the bulk transportation of oil products. In 1877 the first oil tanker, the ‘Zoroaster’, was constructed to his order in Sweden¬. Convinced of the correctness of this direction, he put 100 ¬ bulk tanker wagons onto the Griazi-Tsaritsyn Railway and constructed large warehouses.

Thus, the coming of the Nobels to the Baku ¬oil business resulted in a number of essential changes and technological modernisations to this young branch of industry which determined the ¬future direction of its development.

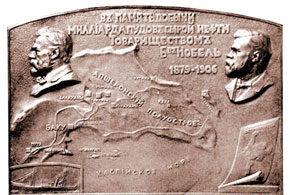

In 1879 the Nobels founded the ‘Nobel Brothers’ Oil Production Association’ with a fixed capital ¬of 3 million roubles. Among ¬the founders of the company were the three brothers, Ludvig, ¬Robert and Alfred Nobel, as well as a colonel in the imperial army, Baron P.A.Bilderling.

The ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ aspired to acquire all the basic elements of the oil industry from the first years of its existence. The company intended to supplant American kerosene in Russia and begin to export oil products. Having created a strong fleet, the ‘Nobel Brothers’ company was already dominant in the transport of kerosene to the¬ Russian domestic market by the early 1880s.

Cooperation

They were also seeking ways to increase exports ¬of oil products to foreign markets. In December 1892, in Rostov-on-Don, a contract was signed to create a ‘Union of Seven Companies’, headed by the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’. Other members of the syndicate were: the ‘S.M.Shibayev Association’, the ‘Caspian Association’, A.I.Mantashev, Z.Taghiyev, G.M.Lianozov and the Budagov brothers. The purpose of the agreement ¬was to establish joint activity in foreign trade. The ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ held the majority of votes in the syndicate.

At the same time Nobel, representing the Union, was entering into agreements with small refiners to acquire all ¬the kerosene they produced. Under these agreements Nobel had the right to reduce the ¬contractors’ annual production and to halt ¬their work if necessary.

Participants in the agreement also agreed on the stabilisation of the domestic market. Apart from the ‘Nobel Brothers’ company, almost all the oil producers conducted their kerosene trade with Russia through ¬commission agents and buyers, not independently. Each company had its own representatives on the main commodity markets and this was very costly. The participants in the contract recognised that the Nobels had established a good basis for the domestic kerosene trade and they decided to entrust “all Russian trade” to the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’.

Thus the formation of the ‘Union of Seven Companies’ gave the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ the opportunity to consolidate in the domestic market, using the largest Baku oil producing companies; a course it followed until the mid 1880s. However, the ‘Union of Seven Companies’ did not last long and soon broke up.

At the beginning of the 1890s, on the one hand, governmental circles wished to increase exports of kerosene, but on the other hand, the producers found themselves in a difficult trading position; this led¬ to the creation of a new syndicate, the “Union of ¬Baku Kerosene Producers”. The Nobels and Rothschilds, who possessed 9610 and 5870 shares respectively, operated the syndicate.

Conflicts between various ¬ groups led to the disintegration of the syndicate in 1897. The main beneficiary of its activity was the Association which, with the help of the Union, had consolidated its position in European markets. By the end of the 1890’s, the Nobel Company had become the largest enterprise in the Baku oil industry. In 1899 it achieved its peak oil production - 93,260 thousand poods (1 pood = 16.8 kg) – which amounted to 17.7% of Russian and 8.6% of the world’s total oil production. The company took a 50.1% share of kerosene sales on the domestic market.

Domination and philanthropy

In the 1880s and 1890s, having occupied key positions in the Baku oil industry the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ expanded its influence and, at the beginning of the 20th century, became the largest ¬concern, uniting more than 20 companies in different branches. By 1917 the total fixed capital of companies directly connected to the Nobels ¬reached 130 million roubles and including subsidiary ¬enterprises of the former “Oil” trust brought it to a total of 215.6 million roubles.

The fact that the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ actively financed scientific research merits attention. The company made an outstanding contribution to the Academy of Sciences by constructing three seismic stations in Baku and Krasnovodsk. The Nobels provided very valuable assistance to Russia’s acquisition of the first device for the study and measurement of photographs of the stars.

They also contributed to landscape gardening in Baku. In 1882-1883, “Villa Petrolea” (Petroleum Villa), a recreation area for employees of the company, was constructed in Black City. The well-known expert E. Bekle, who had built many gardens and parks in Warsaw by this time, was in charge of the villa’s construction. At Bekle’s suggestion, species of trees were brought from Lenkeran, Tbilisi and Batumi, as well as from nurseries in Russia and Europe. About 80,000 bushes and trees, including ¬fruit trees, were planted in the park. The park thus created influenced landscape gardening in the city and on the Absheron peninsula, where the construction of country villas began to develop.

The Baku period of the Nobel brothers’ activity, which started with the founding of a small kerosene factory in 1875, brought them world renown¬. Thanks to their ¬spirit of enterprise, the brothers managed to implement a thorough transformation of the oil industry and, having set the business on a rational foundation, they captured the leading positions in that field.

The Baku enterprises were the main production base for the company’s impressive financial results and in many respects made ¬possible the establishment ¬of the Nobel Prize Foundation following the death of Alfred Nobel. In 1897 the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ already had capital of 32 million roubles and the withdrawal of Alfred Nobel’s share of the sums accumulated created no difficulties for the company’s continued functioning.

Since, by the time the prize fund was established, the deceased Alfred Nobel’s fortune amounted to 31 million Swedish kronor, the following is not difficult to work out: more than 12 percent of this¬ huge sum was earned ¬ not only by the “financial geniuses” in the company but mainly by the labour of its Baku employees. The Swedish historian and financier E. Bergengren, who had access to the Nobel family archives, specially notes in his book about Alfred that the decision by the management of the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ to transfer Alfred Nobel’s share of the Russian company to the prize fund “was the determining factor in the appearance of the Nobel Prize”.

About the authors: Suleyman Aliyarli is a doctor of History and a professor at Baku State University. He is an authority on the history of the oil industry in Azerbaijan. He has written several monographs and a series of articles on pressing questions of Azerbaijani history and the history of the Turks. He is a member of the Turkish Historical Society. He was the editor and principal author of the university textbook on Azerbaijan History.

Arastun Mehtiyev is a candidate of History and senior lecturer at Baku State University. He is the author of more than ten articles and a book on the history of the oil industry in Azerbaijan.

by Suleyman Aliyarli

Arastun Mehtiyev

The Nobel family’s presence in Baku dates from the early 1870s when the oil industry was ¬released from the fetters of the lease system and gradually quickened its development. In fact Robert Nobel was sent to the mountainous areas of Azerbaijan to search for walnut trees for the manufacture ¬of rifle butts in ¬their Izhevsk rifle factory¬. The trip was not successful, however, as the government decided to use cheap and easily produced birch wood instead¬. While in Baku, Robert became familiar with the situation in the oil industry and understood that there were good prospects for profit there. In 1873, after arriving back in St. Petersburg, he convinced his brother Ludvig to invest in Baku’s oil industry¬ and, ¬in 1875, he obtained some oil producing land in Sabunchi district -and set up drilling operations. Robert Nobel also bought a small kerosene factory for ¬25 thousand roubles and began refining oil.

Innovation

The Nobel Brothers realised quite quickly the necessity of a radical transformation ¬ and modernisation ¬of the oil business. Their name became associated with a range of innovations ¬in the industry.

In the 1870s oil was delivered from the fields to the refineries and the coast, as well as to other cities, in barrels; this made industrialists dependent on the carters and barrel manufacturers and was a brake on development and expansion¬. Ludvig Nobel suggested that the producers jointly construct a pipeline connecting oilfields to the refineries and seaports. His proposal was not supported and so, in 1878, he built a pipeline using his company’s own resources. This was soon followed by others and within a year there were already three oil pipelines. Ludvig also developed the bulk transportation of oil products. In 1877 the first oil tanker, the ‘Zoroaster’, was constructed to his order in Sweden¬. Convinced of the correctness of this direction, he put 100 ¬ bulk tanker wagons onto the Griazi-Tsaritsyn Railway and constructed large warehouses.

Thus, the coming of the Nobels to the Baku ¬oil business resulted in a number of essential changes and technological modernisations to this young branch of industry which determined the ¬future direction of its development.

In 1879 the Nobels founded the ‘Nobel Brothers’ Oil Production Association’ with a fixed capital ¬of 3 million roubles. Among ¬the founders of the company were the three brothers, Ludvig, ¬Robert and Alfred Nobel, as well as a colonel in the imperial army, Baron P.A.Bilderling.

The ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ aspired to acquire all the basic elements of the oil industry from the first years of its existence. The company intended to supplant American kerosene in Russia and begin to export oil products. Having created a strong fleet, the ‘Nobel Brothers’ company was already dominant in the transport of kerosene to the¬ Russian domestic market by the early 1880s.

Cooperation

They were also seeking ways to increase exports ¬of oil products to foreign markets. In December 1892, in Rostov-on-Don, a contract was signed to create a ‘Union of Seven Companies’, headed by the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’. Other members of the syndicate were: the ‘S.M.Shibayev Association’, the ‘Caspian Association’, A.I.Mantashev, Z.Taghiyev, G.M.Lianozov and the Budagov brothers. The purpose of the agreement ¬was to establish joint activity in foreign trade. The ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ held the majority of votes in the syndicate.

At the same time Nobel, representing the Union, was entering into agreements with small refiners to acquire all ¬the kerosene they produced. Under these agreements Nobel had the right to reduce the ¬contractors’ annual production and to halt ¬their work if necessary.

Participants in the agreement also agreed on the stabilisation of the domestic market. Apart from the ‘Nobel Brothers’ company, almost all the oil producers conducted their kerosene trade with Russia through ¬commission agents and buyers, not independently. Each company had its own representatives on the main commodity markets and this was very costly. The participants in the contract recognised that the Nobels had established a good basis for the domestic kerosene trade and they decided to entrust “all Russian trade” to the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’.

Thus the formation of the ‘Union of Seven Companies’ gave the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ the opportunity to consolidate in the domestic market, using the largest Baku oil producing companies; a course it followed until the mid 1880s. However, the ‘Union of Seven Companies’ did not last long and soon broke up.

At the beginning of the 1890s, on the one hand, governmental circles wished to increase exports of kerosene, but on the other hand, the producers found themselves in a difficult trading position; this led¬ to the creation of a new syndicate, the “Union of ¬Baku Kerosene Producers”. The Nobels and Rothschilds, who possessed 9610 and 5870 shares respectively, operated the syndicate.

Conflicts between various ¬ groups led to the disintegration of the syndicate in 1897. The main beneficiary of its activity was the Association which, with the help of the Union, had consolidated its position in European markets. By the end of the 1890’s, the Nobel Company had become the largest enterprise in the Baku oil industry. In 1899 it achieved its peak oil production - 93,260 thousand poods (1 pood = 16.8 kg) – which amounted to 17.7% of Russian and 8.6% of the world’s total oil production. The company took a 50.1% share of kerosene sales on the domestic market.

Domination and philanthropy

In the 1880s and 1890s, having occupied key positions in the Baku oil industry the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ expanded its influence and, at the beginning of the 20th century, became the largest ¬concern, uniting more than 20 companies in different branches. By 1917 the total fixed capital of companies directly connected to the Nobels ¬reached 130 million roubles and including subsidiary ¬enterprises of the former “Oil” trust brought it to a total of 215.6 million roubles.

The fact that the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ actively financed scientific research merits attention. The company made an outstanding contribution to the Academy of Sciences by constructing three seismic stations in Baku and Krasnovodsk. The Nobels provided very valuable assistance to Russia’s acquisition of the first device for the study and measurement of photographs of the stars.

They also contributed to landscape gardening in Baku. In 1882-1883, “Villa Petrolea” (Petroleum Villa), a recreation area for employees of the company, was constructed in Black City. The well-known expert E. Bekle, who had built many gardens and parks in Warsaw by this time, was in charge of the villa’s construction. At Bekle’s suggestion, species of trees were brought from Lenkeran, Tbilisi and Batumi, as well as from nurseries in Russia and Europe. About 80,000 bushes and trees, including ¬fruit trees, were planted in the park. The park thus created influenced landscape gardening in the city and on the Absheron peninsula, where the construction of country villas began to develop.

The Baku period of the Nobel brothers’ activity, which started with the founding of a small kerosene factory in 1875, brought them world renown¬. Thanks to their ¬spirit of enterprise, the brothers managed to implement a thorough transformation of the oil industry and, having set the business on a rational foundation, they captured the leading positions in that field.

The Baku enterprises were the main production base for the company’s impressive financial results and in many respects made ¬possible the establishment ¬of the Nobel Prize Foundation following the death of Alfred Nobel. In 1897 the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ already had capital of 32 million roubles and the withdrawal of Alfred Nobel’s share of the sums accumulated created no difficulties for the company’s continued functioning.

Since, by the time the prize fund was established, the deceased Alfred Nobel’s fortune amounted to 31 million Swedish kronor, the following is not difficult to work out: more than 12 percent of this¬ huge sum was earned ¬ not only by the “financial geniuses” in the company but mainly by the labour of its Baku employees. The Swedish historian and financier E. Bergengren, who had access to the Nobel family archives, specially notes in his book about Alfred that the decision by the management of the ‘Nobel Brothers Association’ to transfer Alfred Nobel’s share of the Russian company to the prize fund “was the determining factor in the appearance of the Nobel Prize”.

About the authors: Suleyman Aliyarli is a doctor of History and a professor at Baku State University. He is an authority on the history of the oil industry in Azerbaijan. He has written several monographs and a series of articles on pressing questions of Azerbaijani history and the history of the Turks. He is a member of the Turkish Historical Society. He was the editor and principal author of the university textbook on Azerbaijan History.

Arastun Mehtiyev is a candidate of History and senior lecturer at Baku State University. He is the author of more than ten articles and a book on the history of the oil industry in Azerbaijan.