Pages 48-56

by Thomas Goltz

Road Notes from the New Silk Road Summer Students

Editor’s note: the following vignettes derive from the notes and diary entries of the eight Montana State University participants on the pilot summer trip from Azerbaijan to Istanbul via Georgia, along with one short entry of the Georgian delegate’s first impressions of her American colleagues

Two days in Tbilisi

by Taylor Bezek

After an irritating delay on the Georgia-Azerbaijani border due a visa snafu concerning Laura, we arrived around four in the afternoon, and hit the ground running to see as many of the sights as we could during our truncated stay. That evening our group was treated to a dinner cruise on the Mtkvari (Kura) River by the extremely gracious Georgian affiliates of our unfaltering primary sponsor, SOCAR. Under a full moon, the boat glided up and down the river while we were introduced to khachapuri (‘Georgian pizza’) and Georgian white wine (the man’s wine around these parts) and gazed up at ancient churches and a castle perched on the cliffs above.

…The next day, our final academic destination of the day was to the Free University campus in Tbilisi, our academic partner for the Georgian leg of the New Silk Road trip. The campus consisted of just one building, but was filled with rooms of varying national themes, as the curriculum seemed to be focused on the study of languages and international affairs. For example, there were rooms devoted to the study of China, Japan, Iran, Turkey and the Arabic-speaking world. There was also a “Montana” room’ we posed for pictures in front of the room and were then ushered into a well furnished, media-oriented classroom to watch the movie “Power Trip,” a riveting documentary about the collapse of the power grid in Georgia during the late 90s, and the nearly comic (and failed) efforts of the America energy company AES to fix it.

At the end of the exhausting day, it was off to another lavish, table-buckling dinner provided by our Georgian friends and SOCAR affiliates at a riverside, multi-storey restaurant designed on the theme of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline. Toast followed toast, and talk was interrupted by traditional Georgian singers and dancers. It had been a very rich day in Georgia’s capital...

A meeting with Professor Alexander Rondeli at the GFSIS

by Laura Villegas

The Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies, or GFSIS, is trying to become a classical think tank to help the state identify local skills and leaders that can advance the development of community in each of the Georgian provinces.

The GFSIS is proud of all the projects it is running, its chairman Dr. Alexander Rondeli told us, particularly one concerning the integration of ethnic Azerbaijanis, Armenians and Greeks in Georgia. However, Professor Rondeli tried to avoid calling them “minorities” because he is very aware that it is not a pleasant word: not too long ago, Georgians themselves were also a minority group inside the Soviet Union. According to Dr. Rondeli, the question of maintaining a multi-ethnic society is the most important security issue in the country.

One of the limitations preventing the states of the Caucasus from forming a confederacy seems to be that Georgians and Armenians hate each other even more than Azerbaijanis and Armenians hate each other. Put in Professor Alexander’s words “Anything involving Armenians is more complicated because they have a distorted historical memory…they are even more arrogant than Georgians.”

What about Georgia and Russia?

Dr. Rondeli put it this way: “We are in a cage with a cruel dog that is biting us. Europe just needs to open the cage. Why is it telling us to be nice to the dog?”

Even though it is hard to speak about ‘gains’ when you have just lost a war, Professor Rondeli said that Georgians had indeed gained ‘clarity of mind’ after the August 2008 war. “We are now certain that we are alone in building our state,” he said, adding that Georgians must work, work hard, and work long in normalizing their political, economic, cultural and environmental conditions before they can even start developing their country.

“Georgians must look at everything as a National Security issue,” he said. “Any irresponsible act of the elite has the potential to turn into a disaster.”

The changing face of Tbilisi

by Dan Brooks

The story of Georgia’s emergence from its communist cocoon and evolution into a democratic butterfly can be understood by simply walking the streets and observing the contrast in the city’s structures built before, during and after the 70 year communist experiment that ended in 1991.

Among the remnants of the drab, dreary and uniform socialist housing developments, the traveler is now met by an influx of modern, westernized architecture more reflective of a modern artistic style than an egalitarian social structure.

The pedestrian bridge spanning the Mtkvari (Kura) River is a perfect illustration of the juxtaposition of old and new Tbilisi. The undulating glass shell and triangularly arranged support structure evinces an openness that the Georgian government institutions are trying to project to its citizens, and the acute angles of the support structure remind the observer of Georgia’s communist past: they seem to mirror (or maybe mock) the cold, calculable and oh-so-serious angular facades of the old Soviet system. The newly constructed Ministry of the Interior building suggests the same paradigm. With a population that had an increasingly negative attitude towards government corruption, the current authorities were adamant that the building represent ‘openness.’ The result is a see-through structure made of glass. Walking the spacious halls from floor to floor, one does indeed get a sense of approachability and honesty at the country’s internal security nerve-center, a policy that arguably began in 2005, when President Mikheil Saakashvili fired the entire traffic police force to start again from scratch in a bid to restore public trust in authority.

(I should also note some less-than-perfect efforts to hide Tbilisi’s Soviet-era blemishes. In an effort to cover up the fading edifices adorning what is now George W. Bush Avenue, the government assembled a clean-up crew to hastily tidy up those parts of the city which would be seen by President Bush and his entourage during his May 2005 visit, with workers slathering on generous coats of bright colored paint to the sides of the buildings exposed to the visiting dignitaries. The opposite sides of the buildings received no attention. I believe this is called “a Potemkin Village,” after one of Catherine the Great’s courtiers who made 18th century movie sets of happy villagers along the Volga, during the Czarina’s famous barge tour of her new estates.)

The transparent cop shop

by Richard Gauron

On our second day in Tbilisi, we were fortunate enough to be allowed to have a sit-down at the new Ministry of the Interior with Deputy Minister Shota Utaishvili, who told us about the overhaul of the police force in 2005. The building, a huge steel building skinned in all glass and located off George Bush Boulevard, looked futuristic and foreboding, although it was supposed to stand for the ‘new transparency’ in Georgian security. Other than an occasional picture on the wall, the inside was an extraordinarily sterile mix of metal, glass and granite. Men in suits walked about quickly and with purpose, revealing side-arms beneath their sport coats. (On the way upstairs to our conference room I asked one of our escorts where the restroom was located. Rather than merely pointing, he gestured to an assistant and I was promptly taken to the toilet by a silent, armed guard while security cameras slowly panned the space, giving the whole affair the feeling of a scene out of the movie V for Vendetta or the Novel 1984.)

In the past the Georgian police force had earned a reputation for total corruption. So, after seizing power in the 2003 Rose Revolution, President Saakashvilli and his cohort of reformers decided that they needed to show the population the difference between the new and the old regimes in a concrete manner, and decided to focus on the cops. Overnight, he fired the entire Georgian traffic police force. An interesting and side effect of this radical policy was that there was a period of several months when Georgia had no traffic police while the new recruits were trained; ironically, there was no spike in motor vehicle-related accidents because the existing police force had been so ineffective, due to their preoccupation with extortion. Since then the Georgian police force has become extremely effective and respected—and traffic flows.

The Free University satellite campus on Lake Bazaleti

by Taylor Bezek

Set outside the hustle and bustle of Tbilisi, the Free University satellite campus, called Bazaleti, is located near a lake in the countryside an hour or so away from the capital, and consists of just one building - a mixture of dormitory, cafeteria, and one single, state-of-the-art lecture hall, which was supposedly set up for diplomatic simulations like our model Black Sea Economic Cooperation and Model Arab League debate classes back in Montana. The compact accommodation was complete with plenty of rooms, showers and Internet.

In addition to catching up on email, we were treated to several interesting lectures given by Free University graduate students, one on the subject of Georgian wine and another on the historical and cultural preservation of sites along the current Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline. Perhaps most importantly, our stay at Bazaleti got us out of the traditional hotel dynamic, and helped desegregate the nationality cliques that had begun to set in and make for much greater “mingling” of the Americans, Turks, Azerbaijanis and now Georgians than before.

Of game meat, Gori and the Stalin Museum

By Daniel Brooks

The students awoke on the morning of August 27th at the Free University Training Center in Bazaleti to a bright sunny day after a night of drizzly rain and the BBQ of the now self-described Herder of Cats’ wild game meat feast that I had transported from Montana inside the infamous smuggled meat cooler. The succulent bite-sized portions gave our accompanying Azeri, Turkish and Georgian colleagues a taste of the Big Sky State.

But it was time to leave, and like Pavlovian dogs, we immediately respond to the wheels-up signal by gathering up our gear and boarding the overheated bus. (Some of the youth have started to refer to our dear professor as ‘The Dictator.’)

Our destination was Gori, the hometown and museum of Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, better known as Joseph Stalin. On the way there, we get a quick stop for lunch and are once again afforded the opportunity to puzzle our palate with the previously unknown taste of homemade Georgian wine - about which we had just received a lecture by a Free University professor, who had traced viticulture in Georgia back some 5,000 years. The pleasurable lunch was soon off-set by a quick stop on the road shoulder to take a look at what a Georgian refugee camp looks like. Rows upon rows of small, metal-roofed houses provide shelter for the Georgians who were displaced from the regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia during the 2008 Russian-Georgian war. It was sobering indeed, and discussion shifted from the pleasure of sampling Georgian wine to a comparison of the relative status of refugees in Azerbaijan and Georgia.

Our arrival in Gori brought an undertone of excitement in the student body, who were anxious to visit the Stalin museum. The tour was excellent, with a guide who spoke English gracefully, reflecting her composure and elegant physique. The tour began with Stalin’s background and moved chronologically through his life, ending outside in a tour of his boyhood house, no bigger than an average kitchen, and his Kommisar railcar. The lone disappointment was the lack of souvenirs in the gift shop.

As we left the museum, the HoC decided to garner input from local citizens on their thoughts and perceptions of Stalin. The majority replied that he was a very smart, powerful leader. I can recall only one citizen, out of a dozen, referring to him as a cruel inhumane person. After the museum tour and the interviews, it was apparent that my previous education about Stalin had been less than complete. To some Georgians, at least, he remained a national hero and not a cartoon monster.

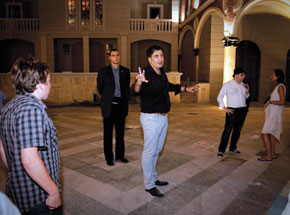

Steven Babbitt stares at Misha Saakashvili at ‘random’ Batumi meeting while bodyguard looks on, Georgia

Steven Babbitt stares at Misha Saakashvili at ‘random’ Batumi meeting while bodyguard looks on, Georgia

Leaving Gori behind, we made our way west, stopping off at the village home of one of our Georgian speakers, Dr Gvantsa, to sample more natural, homemade wine made by her Uncle Gia. It was tart but delicious, and a reminder that seemingly everyone in this country makes their own home brew, as they having been doing for millenia.

A day with the Montana Americans at Bazaleti

by Madlena Goksadze (Free University)

The second day with the MSU students was at the Free University campus at Bazaleti, and I was very excited about going because I had never had any extended contact with a group of Americans before, and was curious about what they are really like. We all have stereotypes about different people and different nations, and the stereotype about Americans in Georgia is mostly from Hollywood films and is quite far from Georgian everyday reality. Accordingly, my mission that day was to make friends with all MSU students and try to understand their character because I had to decide if I wanted to spend the next two weeks with them on the road.

The first thing that I was really surprised at was that American students wrote diaries. I can’t really imagine Georgian guys taking notes on every-day life; it is just not really accepted among Georgian males. The second thing was that after having breakfast, the Americans spent their free time reading books. In Georgia, it would be nearly impossible to find any Georgian boy reading a book after he just woke up (or very, very rare.)

Another thing that surprised me in the beginning was Montana State University Americans’ relationship to Mike Hoyt, an American student at the Free University, who is also from Montana. When he heard that his fellow citizens were coming to our university, he was really excited. But when the MSU students met him, there was no reciprocal excitement. They were very polite, but just didn´t seem to care. If a Georgian meets another Georgia abroad, we greet each other like old friends, even if we have never previously met. The next two weeks were going to be very interesting, and I asked my mother for permission to travel to Istanbul with this crazy group of strangers, so I could study them further.

A visit to Stalin’s hometown

By Richard Gauron

We were greeted by a massive steel fence guarding an ominous-looking building flanked by pillars with very few windows - part house, part official government structure and part mausoleum. Like a Rolls Royce in disrepair, it showed the toll of time. It was the Josef Stalin museum, in the Soviet dictator’s hometown of Gori.

We entered, walking up a massive flight of marble stairs over worn, red carpet held down by scuffed brass runners, and escorted by a beautiful Georgian girl. She spoke in fast and fluent English, but never once smiled during the course of the tour. Room after room was adorned with photos of Stalin taken throughout his life, as well as his uniforms, famous documents associated with him and the lavish gifts he received from dignitaries. One was a monstrous gold desk lamp depicting a T-34 tank, but with built-in clock, humidor and ashtray.

At the far end of the building, we entered a dimly lit, circular room covered in crimson carpet. There was only one object on display here - a surreally small death mask of Stalin. Was this due to the fact that each copy is successively small than the original, or because Stalin’s head was actually tiny? Our stern guide had no answer to this question.

Batumi: The Cancun of the Caucasus

By Taylor Bezek

Characterized by small pebble beaches on the edge of open blue water, and backing up to lush, forest-covered mountains, Batumi seemed like the Cancun of the Caucasus, and one with a pleasant case of identity confusion: with flavors of southern California in its surrounding hills, a reminder of New Orleans in the constant presence of oil tankers lining the horizon and a touch of Miami in the reputation for nightlife, Batumi’s identity crisis is the traveler’s delight.

After a dip in the slightly oily sea, it was off to inspect the 111 hectare, beautifully maintained Batumi Botanical Gardens, perched on the steep hills about nine kilometers north of the city. It was like a taste of the tropics in the former USSR. Next came a tour of the Nobel Museum of Technology, a two-story exhibit of the technological advances the Nobel brothers conceived during the infancy of the oil industry and when Batumi was a city on the international energy map.

After being joined by three new students from Istanbul’s Bilgi University (making the total student group number fifteen), the evening feast was spent in the company of the Deputy Finance Minister, with discussion focused on the future of Batumi and why it has not attracted more foreign investment despite its ports and vacation reputation. (A week later, Donald Trump would announce plans to build a Trump Tower in town).

The morning of the 29th I woke up to the strong smell of crude oil floating into my room from the open door out to my balcony. Packing up on khadjapuri, we said a fond farewell to Batumi, the Black Sea and Sakartvelo—which is what the Georgians call their country in their own language.

NEXT: A Journey to Kars (and eventually, Istanbul)

by Thomas Goltz

Road Notes from the New Silk Road Summer Students

Editor’s note: the following vignettes derive from the notes and diary entries of the eight Montana State University participants on the pilot summer trip from Azerbaijan to Istanbul via Georgia, along with one short entry of the Georgian delegate’s first impressions of her American colleagues

Two days in Tbilisi

by Taylor Bezek

After an irritating delay on the Georgia-Azerbaijani border due a visa snafu concerning Laura, we arrived around four in the afternoon, and hit the ground running to see as many of the sights as we could during our truncated stay. That evening our group was treated to a dinner cruise on the Mtkvari (Kura) River by the extremely gracious Georgian affiliates of our unfaltering primary sponsor, SOCAR. Under a full moon, the boat glided up and down the river while we were introduced to khachapuri (‘Georgian pizza’) and Georgian white wine (the man’s wine around these parts) and gazed up at ancient churches and a castle perched on the cliffs above.

…The next day, our final academic destination of the day was to the Free University campus in Tbilisi, our academic partner for the Georgian leg of the New Silk Road trip. The campus consisted of just one building, but was filled with rooms of varying national themes, as the curriculum seemed to be focused on the study of languages and international affairs. For example, there were rooms devoted to the study of China, Japan, Iran, Turkey and the Arabic-speaking world. There was also a “Montana” room’ we posed for pictures in front of the room and were then ushered into a well furnished, media-oriented classroom to watch the movie “Power Trip,” a riveting documentary about the collapse of the power grid in Georgia during the late 90s, and the nearly comic (and failed) efforts of the America energy company AES to fix it.

At the end of the exhausting day, it was off to another lavish, table-buckling dinner provided by our Georgian friends and SOCAR affiliates at a riverside, multi-storey restaurant designed on the theme of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline. Toast followed toast, and talk was interrupted by traditional Georgian singers and dancers. It had been a very rich day in Georgia’s capital...

A meeting with Professor Alexander Rondeli at the GFSIS

by Laura Villegas

The Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies, or GFSIS, is trying to become a classical think tank to help the state identify local skills and leaders that can advance the development of community in each of the Georgian provinces.

The GFSIS is proud of all the projects it is running, its chairman Dr. Alexander Rondeli told us, particularly one concerning the integration of ethnic Azerbaijanis, Armenians and Greeks in Georgia. However, Professor Rondeli tried to avoid calling them “minorities” because he is very aware that it is not a pleasant word: not too long ago, Georgians themselves were also a minority group inside the Soviet Union. According to Dr. Rondeli, the question of maintaining a multi-ethnic society is the most important security issue in the country.

One of the limitations preventing the states of the Caucasus from forming a confederacy seems to be that Georgians and Armenians hate each other even more than Azerbaijanis and Armenians hate each other. Put in Professor Alexander’s words “Anything involving Armenians is more complicated because they have a distorted historical memory…they are even more arrogant than Georgians.”

What about Georgia and Russia?

Dr. Rondeli put it this way: “We are in a cage with a cruel dog that is biting us. Europe just needs to open the cage. Why is it telling us to be nice to the dog?”

Even though it is hard to speak about ‘gains’ when you have just lost a war, Professor Rondeli said that Georgians had indeed gained ‘clarity of mind’ after the August 2008 war. “We are now certain that we are alone in building our state,” he said, adding that Georgians must work, work hard, and work long in normalizing their political, economic, cultural and environmental conditions before they can even start developing their country.

“Georgians must look at everything as a National Security issue,” he said. “Any irresponsible act of the elite has the potential to turn into a disaster.”

The changing face of Tbilisi

by Dan Brooks

The story of Georgia’s emergence from its communist cocoon and evolution into a democratic butterfly can be understood by simply walking the streets and observing the contrast in the city’s structures built before, during and after the 70 year communist experiment that ended in 1991.

Among the remnants of the drab, dreary and uniform socialist housing developments, the traveler is now met by an influx of modern, westernized architecture more reflective of a modern artistic style than an egalitarian social structure.

The pedestrian bridge spanning the Mtkvari (Kura) River is a perfect illustration of the juxtaposition of old and new Tbilisi. The undulating glass shell and triangularly arranged support structure evinces an openness that the Georgian government institutions are trying to project to its citizens, and the acute angles of the support structure remind the observer of Georgia’s communist past: they seem to mirror (or maybe mock) the cold, calculable and oh-so-serious angular facades of the old Soviet system. The newly constructed Ministry of the Interior building suggests the same paradigm. With a population that had an increasingly negative attitude towards government corruption, the current authorities were adamant that the building represent ‘openness.’ The result is a see-through structure made of glass. Walking the spacious halls from floor to floor, one does indeed get a sense of approachability and honesty at the country’s internal security nerve-center, a policy that arguably began in 2005, when President Mikheil Saakashvili fired the entire traffic police force to start again from scratch in a bid to restore public trust in authority.

(I should also note some less-than-perfect efforts to hide Tbilisi’s Soviet-era blemishes. In an effort to cover up the fading edifices adorning what is now George W. Bush Avenue, the government assembled a clean-up crew to hastily tidy up those parts of the city which would be seen by President Bush and his entourage during his May 2005 visit, with workers slathering on generous coats of bright colored paint to the sides of the buildings exposed to the visiting dignitaries. The opposite sides of the buildings received no attention. I believe this is called “a Potemkin Village,” after one of Catherine the Great’s courtiers who made 18th century movie sets of happy villagers along the Volga, during the Czarina’s famous barge tour of her new estates.)

The transparent cop shop

by Richard Gauron

On our second day in Tbilisi, we were fortunate enough to be allowed to have a sit-down at the new Ministry of the Interior with Deputy Minister Shota Utaishvili, who told us about the overhaul of the police force in 2005. The building, a huge steel building skinned in all glass and located off George Bush Boulevard, looked futuristic and foreboding, although it was supposed to stand for the ‘new transparency’ in Georgian security. Other than an occasional picture on the wall, the inside was an extraordinarily sterile mix of metal, glass and granite. Men in suits walked about quickly and with purpose, revealing side-arms beneath their sport coats. (On the way upstairs to our conference room I asked one of our escorts where the restroom was located. Rather than merely pointing, he gestured to an assistant and I was promptly taken to the toilet by a silent, armed guard while security cameras slowly panned the space, giving the whole affair the feeling of a scene out of the movie V for Vendetta or the Novel 1984.)

In the past the Georgian police force had earned a reputation for total corruption. So, after seizing power in the 2003 Rose Revolution, President Saakashvilli and his cohort of reformers decided that they needed to show the population the difference between the new and the old regimes in a concrete manner, and decided to focus on the cops. Overnight, he fired the entire Georgian traffic police force. An interesting and side effect of this radical policy was that there was a period of several months when Georgia had no traffic police while the new recruits were trained; ironically, there was no spike in motor vehicle-related accidents because the existing police force had been so ineffective, due to their preoccupation with extortion. Since then the Georgian police force has become extremely effective and respected—and traffic flows.

The Free University satellite campus on Lake Bazaleti

by Taylor Bezek

Set outside the hustle and bustle of Tbilisi, the Free University satellite campus, called Bazaleti, is located near a lake in the countryside an hour or so away from the capital, and consists of just one building - a mixture of dormitory, cafeteria, and one single, state-of-the-art lecture hall, which was supposedly set up for diplomatic simulations like our model Black Sea Economic Cooperation and Model Arab League debate classes back in Montana. The compact accommodation was complete with plenty of rooms, showers and Internet.

In addition to catching up on email, we were treated to several interesting lectures given by Free University graduate students, one on the subject of Georgian wine and another on the historical and cultural preservation of sites along the current Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline. Perhaps most importantly, our stay at Bazaleti got us out of the traditional hotel dynamic, and helped desegregate the nationality cliques that had begun to set in and make for much greater “mingling” of the Americans, Turks, Azerbaijanis and now Georgians than before.

Of game meat, Gori and the Stalin Museum

By Daniel Brooks

The students awoke on the morning of August 27th at the Free University Training Center in Bazaleti to a bright sunny day after a night of drizzly rain and the BBQ of the now self-described Herder of Cats’ wild game meat feast that I had transported from Montana inside the infamous smuggled meat cooler. The succulent bite-sized portions gave our accompanying Azeri, Turkish and Georgian colleagues a taste of the Big Sky State.

But it was time to leave, and like Pavlovian dogs, we immediately respond to the wheels-up signal by gathering up our gear and boarding the overheated bus. (Some of the youth have started to refer to our dear professor as ‘The Dictator.’)

Our destination was Gori, the hometown and museum of Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, better known as Joseph Stalin. On the way there, we get a quick stop for lunch and are once again afforded the opportunity to puzzle our palate with the previously unknown taste of homemade Georgian wine - about which we had just received a lecture by a Free University professor, who had traced viticulture in Georgia back some 5,000 years. The pleasurable lunch was soon off-set by a quick stop on the road shoulder to take a look at what a Georgian refugee camp looks like. Rows upon rows of small, metal-roofed houses provide shelter for the Georgians who were displaced from the regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia during the 2008 Russian-Georgian war. It was sobering indeed, and discussion shifted from the pleasure of sampling Georgian wine to a comparison of the relative status of refugees in Azerbaijan and Georgia.

Our arrival in Gori brought an undertone of excitement in the student body, who were anxious to visit the Stalin museum. The tour was excellent, with a guide who spoke English gracefully, reflecting her composure and elegant physique. The tour began with Stalin’s background and moved chronologically through his life, ending outside in a tour of his boyhood house, no bigger than an average kitchen, and his Kommisar railcar. The lone disappointment was the lack of souvenirs in the gift shop.

As we left the museum, the HoC decided to garner input from local citizens on their thoughts and perceptions of Stalin. The majority replied that he was a very smart, powerful leader. I can recall only one citizen, out of a dozen, referring to him as a cruel inhumane person. After the museum tour and the interviews, it was apparent that my previous education about Stalin had been less than complete. To some Georgians, at least, he remained a national hero and not a cartoon monster.

Steven Babbitt stares at Misha Saakashvili at ‘random’ Batumi meeting while bodyguard looks on, Georgia

Steven Babbitt stares at Misha Saakashvili at ‘random’ Batumi meeting while bodyguard looks on, Georgia Leaving Gori behind, we made our way west, stopping off at the village home of one of our Georgian speakers, Dr Gvantsa, to sample more natural, homemade wine made by her Uncle Gia. It was tart but delicious, and a reminder that seemingly everyone in this country makes their own home brew, as they having been doing for millenia.

A day with the Montana Americans at Bazaleti

by Madlena Goksadze (Free University)

The second day with the MSU students was at the Free University campus at Bazaleti, and I was very excited about going because I had never had any extended contact with a group of Americans before, and was curious about what they are really like. We all have stereotypes about different people and different nations, and the stereotype about Americans in Georgia is mostly from Hollywood films and is quite far from Georgian everyday reality. Accordingly, my mission that day was to make friends with all MSU students and try to understand their character because I had to decide if I wanted to spend the next two weeks with them on the road.

The first thing that I was really surprised at was that American students wrote diaries. I can’t really imagine Georgian guys taking notes on every-day life; it is just not really accepted among Georgian males. The second thing was that after having breakfast, the Americans spent their free time reading books. In Georgia, it would be nearly impossible to find any Georgian boy reading a book after he just woke up (or very, very rare.)

Another thing that surprised me in the beginning was Montana State University Americans’ relationship to Mike Hoyt, an American student at the Free University, who is also from Montana. When he heard that his fellow citizens were coming to our university, he was really excited. But when the MSU students met him, there was no reciprocal excitement. They were very polite, but just didn´t seem to care. If a Georgian meets another Georgia abroad, we greet each other like old friends, even if we have never previously met. The next two weeks were going to be very interesting, and I asked my mother for permission to travel to Istanbul with this crazy group of strangers, so I could study them further.

A visit to Stalin’s hometown

By Richard Gauron

We were greeted by a massive steel fence guarding an ominous-looking building flanked by pillars with very few windows - part house, part official government structure and part mausoleum. Like a Rolls Royce in disrepair, it showed the toll of time. It was the Josef Stalin museum, in the Soviet dictator’s hometown of Gori.

We entered, walking up a massive flight of marble stairs over worn, red carpet held down by scuffed brass runners, and escorted by a beautiful Georgian girl. She spoke in fast and fluent English, but never once smiled during the course of the tour. Room after room was adorned with photos of Stalin taken throughout his life, as well as his uniforms, famous documents associated with him and the lavish gifts he received from dignitaries. One was a monstrous gold desk lamp depicting a T-34 tank, but with built-in clock, humidor and ashtray.

At the far end of the building, we entered a dimly lit, circular room covered in crimson carpet. There was only one object on display here - a surreally small death mask of Stalin. Was this due to the fact that each copy is successively small than the original, or because Stalin’s head was actually tiny? Our stern guide had no answer to this question.

Batumi: The Cancun of the Caucasus

By Taylor Bezek

Characterized by small pebble beaches on the edge of open blue water, and backing up to lush, forest-covered mountains, Batumi seemed like the Cancun of the Caucasus, and one with a pleasant case of identity confusion: with flavors of southern California in its surrounding hills, a reminder of New Orleans in the constant presence of oil tankers lining the horizon and a touch of Miami in the reputation for nightlife, Batumi’s identity crisis is the traveler’s delight.

After a dip in the slightly oily sea, it was off to inspect the 111 hectare, beautifully maintained Batumi Botanical Gardens, perched on the steep hills about nine kilometers north of the city. It was like a taste of the tropics in the former USSR. Next came a tour of the Nobel Museum of Technology, a two-story exhibit of the technological advances the Nobel brothers conceived during the infancy of the oil industry and when Batumi was a city on the international energy map.

After being joined by three new students from Istanbul’s Bilgi University (making the total student group number fifteen), the evening feast was spent in the company of the Deputy Finance Minister, with discussion focused on the future of Batumi and why it has not attracted more foreign investment despite its ports and vacation reputation. (A week later, Donald Trump would announce plans to build a Trump Tower in town).

The morning of the 29th I woke up to the strong smell of crude oil floating into my room from the open door out to my balcony. Packing up on khadjapuri, we said a fond farewell to Batumi, the Black Sea and Sakartvelo—which is what the Georgians call their country in their own language.

NEXT: A Journey to Kars (and eventually, Istanbul)