Pages 28-31

Pages 28-31It was a beautiful house – 2 storeys – with grape vines that climbed over the balconies.... Address? We didn’t have an address; everybody knew our house near the river. There was a big garden with apple, pear and plum trees, and potatoes.... my father loved boiled potatoes, and rice soup.... One of the apple trees was very small; every year it had just 3 apples, and we were three children. The apples smelled of honeydew melons and one day I took a bite out of one of them, but I left it on the tree; my father asked, ‘Why didn’t you pick it?’

Yasemen Hasanova’s eyes are bright with the memories of her childhood home. She tells of the wonderful views from the upstairs window, of gazing out at the town up on the heights in the distance – that town’s lights against the night sky were a thing of wonder to a child. They often went up there in her father’s yellow Moskvich to take long walks. It was difficult to walk anywhere in our town. My father had so many friends and was very sociable; he loved to talk. Whenever we had to go somewhere my mother asked him not to stop and talk, or we would never get there.

Yasemen khanim lives in very basic conditions now, in a settlement on the coast of the Caspian Sea, not far from Baku. She teaches children in their first year at school and she loves to tell them about life in the town of her childhood. She takes particular delight in the open lessons she organises in which the children describe the town in all its beauty, as if they had seen it with their own eyes.

Ask any child, they can all describe Khojaly. She could hardly have imagined twenty years ago that one day she would become a teacher. For the last 18 months of her life in her home town she hardly went to school – she recalls only being there for one month in what should have been her 6th year of education.

When she left her town, aged 12, it was in the middle of the night, on foot and without her parents. She, her sister Afsane (10 at the time) and brother Murad (8) had 10 or so kilometres to walk, across a river and through a forest. It was snowing heavily that February night, and they would meet a hail of bullets on the way past Nakhchivanik, but the townsfolk of Khojaly had two options: walk, or die.*

Some sort of schooling was organised for those children who were not killed on the way to Aghdam. One of her friends told Yasemen that her mother was alive and staying at a certain house. She knocked on the door and asked the old woman who answered if her mother was there. What could the old woman say to a 12 year old?

She’ll come tonight.

She was never to see her mother or father again; the Armenian attack and ambush also took her grandparents, an uncle and an aunt and her two children (Yasemen’s cousins).

********

The children had not been able to understand the constant noise of the previous months; especially at night, when the sky was lit as if by fireworks. Yasemen’s father explained that these displays were dangerous and could damage houses and kill people; he couldn’t explain, though, why people who had eaten and drunk with them were now trying to kill them. The children were always in their day clothes and spent many nights in their cellar. Her father taught military skills at school and was commander of the town’s defence force, so he was always out at night until the noise and lights stopped, around 5 or 6am.

There were food shortages, especially flour and bread, the gas and electricity was cut, we cooked on wood fires, and our boys had no weapons like tanks....Khojaly was surrounded, like a tea glass on a saucer, the only way out was by helicopter, and they shot at that....Once, when my uncle was taking us to our grandfather’s house, they started firing and my uncle lay down on top of us; grandfather’s gate was all shot up....They were shooting at us every day, but my father continued fixing up the house, preparing for my brother’s circumcision party.

On the night of 25-26 February 1992 it became more serious and the Armenians were advancing. The call came to leave everything and head for Aghdam. First came the river – some survivors tell of clothes having to be left behind, frozen solid and too heavy to carry after the wade through the water. They headed for the forest, a hoped-for refuge from the searchlights and the bullets.

My father liked eating and we had kebabs on picnics near the forest.

The snow threatened, and inflicted frostbite on those who’d discarded shoes to cross the river – it also spotlit the blood of friends, neighbours and loved ones whose bodies became barriers to cross or shields to – please! - stop the bullets.

The air was always clean and clear, and I remember snow on the 8 March and Novruz holidays. With so many relatives nearby, we always had good holidays.... our relatives from Baku visited when they knew my father was at home. I left all my holidays in Khojaly.

Some three weeks later a body was returned to the Azerbaijani side. At first the children were told it was their grandfather, but:

The day he was buried, my brother Murad was given a picture of my father. His tears ran over the picture; it seemed the picture was crying.

Tofiq Huseynov now lies in Martyrs’ Avenue, overlooking Baku.

My father always slept on his back with his arms crossed and he would talk in his sleep about the events of the day.... I often visit his grave. I think that he could get up and talk about everything that happened.

Like many orphaned on that freezing, bullet-riddled Wednesday morning, Yasemen, her sister and brother were taken into relatives’ homes; they were brought up by their aunt and uncle. She studied at different schools and graduated as a teacher.

She is married now, her husband is also from Khojaly, and they have two daughters: Leman, 9, and Leyla, just 1 year old.

We are mothers ourselves now, but still we want to see our own mothers.... they took our mother’s love from us.

She glances up at the sole surviving picture of her parents, high on the wall of the living room.

Her mother, Mehmer, had stayed behind on that night; sending her three children to what she thought was safety with their uncle and aunt, she refused to leave without her husband and waited for his return from the defence post. 16 years later, a picture of her body was recognised in a picture on the internet – it seemed she had been getting water from the well in the garden when she was shot down.

I never imagined that any daughter could thank God that her mother was dead.... I thank God she died there, instead of being tortured by Armenians.

56 families, nearly all from Khojaly, live in the settlement, a dilapidated former Soviet sanatorium. There are 250 or so children who attend Khojaly School No 2, named after the school in which Tofiq Huseynov taught.

All the boys want to be soldiers or policemen, the girls want to be doctors or teachers.

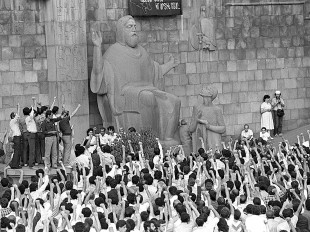

Heroes

“The Minsk Group spearheads the OSCE’s efforts to find a political solution to the conflict in and around Nagorno-Karabakh involving Armenia and Azerbaijan” (http://www.osce.org/mg).

For 19 years the di plomats and politicians of the OSCE Minsk Group have spearheaded backwards and forwards through the hotels of Europe, the US and the Caucasus; no doubt they will be rewarded and honoured for their efforts.

Yasemen Hasanova’s father died defending his town against overwhelming odds – now lying in a hilltop cemetery, he is Azerbaycanin Milli Qehremani, a National Hero of Azerbaijan.

His daughter walked through the snow of a freezing winter’s night, escaped the bullets and endured the loss of parents, relatives and neighbours. She persevered through a succession of schools to graduation. Lodged in a crumbling sanatorium, she is bringing up her own two children and educating those of her surviving neighbours in the beauty of the land she lost. Her reward....

I see Khojaly in my dreams. I wake up and close my eyes again to continue the dream.... I live with the hope that we will open the closed doors.

There are many forms of heroism.

*see http://wikimapia.org/524432/Khojaly for an idea of the terrain crossed on the Tuesday/Wednesday night, 25/26 February 1992