Pages 94-97

Pages 94-97by Ziyadkhan Aliyev

*Ex-libris - a label bearing the owner´s name and an individual design or coat of arms, pasted into a book, a bookplate

Azerbaijan may have seen some of the first bookplates produced. One that has survived was drawn by Behtishi for the work titled Manfi al-Hayvan (the manuscript is preserved in the Morgan library, New York) and inscribed by Azerbaijani craftsmen in Maraga in 1297-1299. The name of the book’s owner, Shamsaddin ibn Zusheki was written in dainty handwriting inside an embellished khoncha (a plate) which was shaped as an eight-pointed star shape. We should note that Shamasaddin was an eminent vizier under Hulaki rule (1256-1357). He was an influential scientist in his time and also wrote poetry and letters. He was executed by order of Argun khan in Tabriz…

The first versions of Azerbaijani bookplates consisted of images and inscriptions on precious stones and metals. Originally, they were used for many purposes by their owners, including as a mark of ownership of the books in their libraries. The academic historian A. Nuriyev, in his work entitled From the History of craftsmanship in Caucasian Albania, wrote about engravings and stone plates bearing the images of people and animals being found on the territory of Azerbaijan during archaeological excavations.

95 camel-loads of books

Personal seals and plates on ancient manuscripts provide the richest material to study the history of the art of the bookplate. Many consist of samples and traceries of dainty calligraphy which delight the eye. In most cases seal-plates were used instead of ex-libris by authors and calligraphers when copying books, as well as by the owners of books confirming their ownership in this way. With the increasing establishment of private libraries in Azerbaijan, the number of personal seals and bookplates also increased. Collectors began to order seal-bookplates in various sizes and shapes, as well as with attractive images. The historical establishment of wealthy libraries in Maraga (13th century, the famous astronomer, Khaje Nasreddin Tusi’s library); Tabriz (13th-14th centuries, Shah Ismayil Khatai’s palace library); Shamakha (12th century, the library of Kafiyeddin, uncle of the poet Khagani); Shusha (19th century, the library of historian and writer Bahman Mirza Gajar) and other cities, confirms the centuries-long history of Azerbaijani bookplates. The libraries of Rashidaddin Fazllulah and Khaje Nasreddin Tusi contained 60 and 400 thousand books respectively. When moving to Shusha, it took 95 camels to carry Bahman Mirza Gajar’s valuable manuscripts and books. Of these bibliophiles, Bahman Mirza Gajar owned most bookplates. 9 of his bookplates have survived in various forms.

The Kurani-Kerim (Koran) (currently held in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin) which was inscribed in 1338 in Maraga, has outstanding artistic features. The master calligrapher Abdullah Ahmed Maragayi displayed unsurpassed craftsmanship in copying it in Naskh script (also known as Naskhi, this is a specific calligraphic style for writing in the Arabic alphabet) and the decorative appearance of the pages, but mainly in depicting the bookplate. The first page of the manuscript is embellished with an ex-libris of original shape, consisting of a plate with a six-pointed star in the centre and 12 leaves on the borders. In the centre, in blank spaces between the traceries there is skilfully written in Kufic script (Kufic is the oldest calligraphic form of the various Arabic scripts) the following sentence, “Only pure people can touch this book sent by the Creator”.

Floral patterns were used as a decorative solution for the ex-libris in the book Chemistry of Happiness (14th century), written and decorated by a craftsman from Shamakha, Abdul Rahman ibn Abdul Aziz, and currently preserved in the Evkaf Museum in Istanbul. The composition was completed with the customer’s, Prince Husheng, name written in the Kufic script.

There is the tastefully worked ex-libris by Baysangur Mirza in a copy of Sadi Shirazi’s work Gulustan which, in its time, adorned Baysangur Mirza’s library and is now preserved in the Chester Beatty collection in Dublin; it was copied by Jafar Tabrizi from Tabriz, in Herat in 1426, in the Nastalīq script (also anglicized as Nastaleeq, this is one of the main script styles used in writing the Perso-Arabic script, and traditionally the predominant style in Persian calligraphy).

The cover page of a manuscript written in Bagdad in 1465, in the declining years of the Garagoyunlu state, is full of different personal seals alongside the main ex-libris, which was drawn manually. It confirms the successive ownership of the Divan (a collection of one poet’s works) by different people.

An early 15th century copy of Nizami Ganjavi’s poem Khosrov and Shirin has a plate-shaped ex-libris worked up in gold colour by the Tabriz-based calligrapher Ali ibn Hasan Sultani. Written in the Nastaliq script, it exemplifies the highest craftsmanship; it is currently held in the Freer Gallery in Washington.

A floral patterned ex-libris on the inside cover of the Kurani-Kerim (Koran) was written in the Naksh script by the calligrapher Aladdin Muhammad Tabrizi in the 14th century in Tabriz. It indicates that the book was held in Shah Ismayil’s library. The manuscript is now in the Tehran library.

The artistic development of Azerbaijani bookplates between the 18th and 19th centuries can be observed in examples decorating the manuscripts kept in the libraries of Prince Sultan Huseyn (18th century); the poet Mirza Shafi Vazeh (19th century); historian and philosopher Abbasgulu Aga Bakikhanov (19th century); the renowned commander Abbas Mirza Gajar (19th century); the chronicler Bahman Mirza Gajar (19th century); the dramatist Mirza Fatali Akhundov (19th century) and others. All were written in Arabic script.

In praise of God and man

These attractive artistic adornments, as well as naming the book owner, often included a variety of expressions, many of which were religious in content. Thus, in books belonging to M.F. Akhundov’s library we meet the phrase “the servant of God, Fatali” in some dainty copies from Abbasgulu Aga Bakikhanov’s library the phrase “He is God; there is no God but He”; Shah Ismayil Khatai had the words “Ismayil son of Heydar is the servant of Shaimardan” (Shaimardan is the Imam Ali) inscribed in his books; and the phrase “Ya Muhammad” appears in the books of Mirza Shafi Vazeh.

Apart from the bookplates, there were also mottos: “A book is a heart-warming blessing”, “It belongs to me now, afterwards it will belong to others” in Abbasgulu Aga Bakikhanov’s books and “Bahman, the only jewel in the vastness of the kingdom” etc. praised Bahman Mirza Gajar.

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, bibliophiles used bookplates and stamps in simpler forms. Bookplates written mainly in Russian and Arabic belonged to statesman Nariman Narimanov, educationist Sultan Majid Gani-Zadeh, the painter Bahruz Kengerli, General Ibrahim Aga Vekilov, folklore specialist Abulgasim Huseyn-Zadeh and People’s Artist Mirza Aga Alityev.

The first bookplates created after the Soviet occupation in Azerbaijan generally took Lenin and the Revolution as their main themes. S. Telingater and L. Knit, who were working then in Baku, were responsible for most of them. Later, local painters took on the work. Particularly interesting were the bookplates of Alekbar Rzaguliyev, an artist known for his sharply observed series of graphics “Old Baku”; his bookplates were devoted to Azerbaijani intellectuals and were distinguished by their artistry and subtle humour. The sixties saw a flourishing of ex-libris in the Republic. Bookplates by Jamil Mufti-Zadeh devoted to the venerable inhabitant of the planet, Shirali Muslumov (reputed to have lived more than 160 years when he died in 1975), those of Rashid Mirishli, devoted to the poet Nasimi and Alekbar Rzaguliyev’s devotions to the philosopher Shukufa Mirzayeva are remarkable for their compressed composition and memorable images.

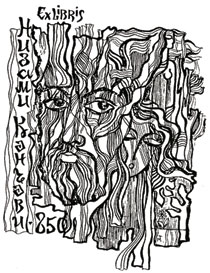

The bookplates created by the painters Arif Huseynov, Bayram Gasimkhanli, Faig Ibrahimov, Arif Azizov, Fuzuli Akhundov and Ogtay Guliyev in the 1970s and 80s were noted for their improvisation and creative vision. The images and interests of painters Tahir Salahov and Togrul Narimanbeyov, the poet Fikret Goja, writers Elchin and Anar, architect Jafar Giyasi, music historian Firudin Shushali, carpet-maker and painter Latif Kerimov, conductor Niyazi and other eminent people were depicted.

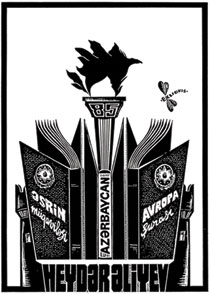

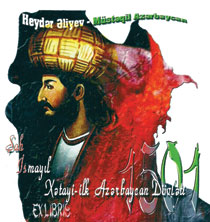

There have been international ex-libris competitions and exhibitions in Azerbaijan devoted to famous figures; the competitions Shah Ismayil Khatai – 500 and Nizami Ganjavi – 850 among them.

Bookplates are now widespread in Azerbaijan and they are in increasing demand. It is encouraging to see the continuation and modernisation of this artistic tradition.

About the author: Ziyadkhan Aliyev is an Honoured Art Worker of the Azerbaijan Republic and the author of monographs and articles devoted to music, painting and other Azerbaijani arts.