Pages 20-23

Pages 20-23by Jeffrey Werbock

“There was nothing even a close second”

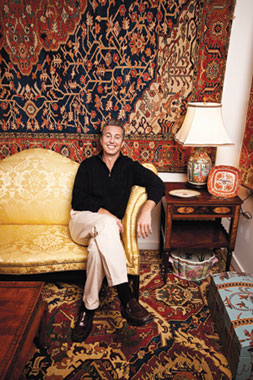

Jeffrey Werbock is one of Azerbaijan’s favorite Americans. Well-known and respected for his expertise in mugham, he also has a passion for the antique carpets (‘rugs’ to Americans) produced here. Some years ago he was surprised to discover that independent Azerbaijan was again producing top quality carpets, based on traditional forms. He owed this discovery to Richard Rothstein, an American carpet enthusiast and dealer. We asked for more details and after an introduction, Jeffrey fired the questions. Please introduce yourself

My name is Richard Rothstein and I’m a rug dealer.

I’ve been dealing rugs for about 10 years, but I grew up with parents who collected antique rugs, so I’ve been around them all my life. I love rugs, I’ve always loved rugs and I guess it’s a love affair. So I grew up with them, I have them in my home, in my business and I traveled all throughout Azerbaijan and other parts of the world in my quest for rugs

How did you get started?

I got started in the rug business because my family collected antique rugs and when I was about 25 I wanted to buy new rugs for my home and I couldn’t find any rugs that were compatible with the old rugs that I was familiar with. So I started researching where I could find new rugs that were made like the old rugs and that ultimately led me to produce rugs and travel to the Caucasus, specifically to Azerbaijan. There I found the greatest new rugs that were available in the marketplace. There was nothing even a close second; the dyes, the materials, the workmanship were identical to the old rugs, in fact the only difference between new rugs that we were having produced and the old rugs was the fact the new rugs were new.

Would you consider yourself a merchant or an artist?

Well, I wish I could weave rugs, I’ve tried and I’m not very good at it, so I guess I would consider myself to be a bit of both. I love what the rugs represent, I love the feel of the rugs, meaning the emotion behind them, the story behind them, but in a sense I am a merchant and I deal in rugs, but I don’t consider it as selling carpets, I do consider it as selling a [form of] art….

How was it growing up around oriental rugs and antiques?

I fell in love with rugs because I grew up with them, they were in my house since I can remember, so we had hardwood floors and oriental rugs and I… [played]… on the rugs and the colors and the designs and some of the rugs are fun, they have animal figures in them or human figures or in the case of a rug called Aqstafa there are magical birds which are similar to phoenixes. There’s a lot going on, it’s not what most people think of when they think of an Oriental rug, which maybe is a large neutral color or burgundy color rug they saw at their grandparents. The rugs I grew up with were smaller, they had stripes on them, they had vivid colors and once that is something you’re accustomed to when you think of an oriental rug then that’s what I wanted to acquire when I was an adult and it wasn’t available in new rugs.

….[You should] buy what you like, but know what you’re buying and it’s obviously important that you like the rug, but it’s also important to know where the rug was made, who made the rug, what region it comes from, what materials, is it made from natural dyes or synthetic dyes? Is it a design based on a historical piece? ….Dealers have an obligation to tell the consumers this is what you’re acquiring, this is where it was made, this is when it was made, this is what it was made from, this is who made it and that is something I would like to see change in the industry.

I think that, at least in America, almost everyone has an oriental rug or knows someone who has an oriental rug, but I don’t think that many people know the history and the traditions behind it, what are the elements; when you see a symbol on a rug what does it mean? Why is it there? They have a history behind them and they have a story to tell.

Jeffrey: So Richard the last time you and I saw each other in front of a camera we were in Baku together, remember? Was that three or four years ago?

Richard: Yes. It was four years ago

J: I know it was October, right. And we were in Vidadi’s showroom, his Azer-Ilme carpet showroom….It is vivid in my mind and I tell the story to my friends all the time, I walked into this little carpet showroom in the middle of Haddonfield, New Jersey, and I saw this beautiful Azerbaijani design carpet hanging in the window. I knew it was a new one and I knew what the Bolsheviks had done to the Azerbaijani carpet trade; it went from the highest quality carpets in the world to possibly the lowest, and so I walked in and said “Where is this from?” you said “Azerbaijan” and I started to argue. And you said “No! This was made in Azerbaijan, by Azerbaijani people, it’s the real thing”. And I was so shocked by the high quality I called Seymur on the phone and you complained you tried to get a hold of him for three weeks…

R: I’ve been trying to call this guy and you just pull out your phone and speed dial…

J: And then I switched to Azerbaijani and got you upset, and I said, “I know who’s making your rugs”. So we have been friends ever since and you seem to be the only carpet dealer anywhere who is actually using the word Azerbaijan to describe the provenance of the carpet and I think that people need to know that when it comes to antiques in general, the single most important thing is provenance and yet for some reason the carpet dealers, the carpet auction showrooms and even carpet scholars, neglect to use the word Azerbaijan, they call them Caucasian…

R: And Northwest Persian

J: …and you are the only man insisting on the proper terminology, the word Azerbaijan, and I’ve noticed, for example, Baluchis live in Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, but when a Baluchi weaves a carpet it’s called a Baluch

R: Right

J: Or Kurdish people, they live in Iraq, Turkey, Syria, Iran and Azerbaijan, but no matter what country they’ll be living in, if a Kurd wove a carpet they call it a Kurdish carpet, but what happened to Azerbaijanis?

R: It’s a good question, it’s a complicated question and it’s a question that doesn’t have a definitive answer.

J: Well, let’s speculate. First of all, who controlled the carpet trade a hundred years ago?

R: Well, in the west it was primarily Armenians and Persians.

J: So the Armenian and Persian carpet dealers were controlling the trade and were the ones who gave the names to where the carpet came from.

R: I think it’s a combination of the dealers, the scholars, the institutions, the museums, I don’t think you can pinpoint one specific area. The analogy I give is that it would be no different than calling French wine European wine, ‘this is the best European wine I’ve ever had’, yes it’s true French wine is European wine, but… a Quba…. yes, it’s a Caucasian rug, but a Quba comes from Quba, which is in Azerbaijan, same as Shirvan, same as Talysh, same as Lezghi and that is kind of lost in translations and it’s unfortunate. It’s especially so when you see the most sought after in the antique market for Persian rugs are Northwest Persian rugs.

J: You mean Iran?

R: Northwest Persian rugs drive the high end museum quality antiques and they are Serapis, Heriz, Tabriz and Bakshaish

J: But those are Azerbaijani towns. Those are towns populated by ethnic Azerbaijanis living in the country of Iran

R: Yes, but dealers today still call these Persian carpets; Sotheby’s does, Christie’s does and the truth is the original Azerbaijani designs are woven by Azerbaijanis in what is today, depending on who you talk to, Iranian Azerbaijan, South Azerbaijan, Persian Azerbaijan. So a Serapi, a Heriz, these rugs are in the White House, they are in the State Department; when heads of state come to what is called a diplomatic reception room, these rugs are Azerbaijani carpets, they are Serapis, Herizes, Tabrizis.

J: And what about the Caucasus, so called Caucasian carpets, who is weaving them?

R: Well historically, if you look at the Caucasus, Quba and Shirvan are cities obviously in Azerbaijan, and Karabakh and Kazakh as well.

J: Would you speculate on the percentage? For example you said approximately half of the so called Persian carpets woven in that area are actually woven by Azerbaijani people living in that part of Iran, what percentage would you say of so-called Caucasian carpets are woven by Azerbaijanis?

R: What people have told me, and I’ve had discussions for many years, [is] that about 90 per cent of all Caucasian rugs are really Azerbaijani carpets and it’s important that people understand these are regions, these are locations, these are places with latitude and longitude, they really exist. Pirebedil, you list all the various names, Talysh, Quba, these are actual places that exist in Azerbaijan.

J: Have you been to any of these places?

R: Yes, I have been to most of them. Qonakhkend, Pirebedil, Zeyve, these are regions around Quba.

J: What is it that you love about these carpets?

R: It’s everything. It’s difficult to articulate. Part of it is my background, part of it is that it’s an incredible art form. It is powerful, sublime…first of all they’re so hard to make, people don’t realize; they think it’s just a carpet. It’s labor intensive, it is so difficult. And when you think about the history behind the carpets, they just do something. It’s the synergy, the color, it’s the design, it’s the material, the wool.

J: Provenance is the principle of an object of beauty belonging to a particular territory. And that’s what we’re trying to clarify. When I first started learning about carpets in the early 70s, I heard the distinction was Persian carpets, Caucasian carpets, Turkish carpets….

R: That’s the big three. Generally speaking Anatolian, Caucasian, Persian

J: When I first discovered the beauty and the charm of Oriental carpets, my eye was instantly attracted to what was called Caucasian and of course in America no one taught us in school about the Caucasus Mountains: who are these people? So when I looked at these carpets, with their outrageous geometries, I thought this is incredibly sophisticated and yet, I understand those people who wove the carpets were illiterate people, they were not formally trained, and they didn’t just copy each other, they improvised, they made distinctive versions of a common theme, for example you mentioned Pirebedil before; we can see a carpet and say it’s Pirebedil because of the particular daggers and shields and stylized rams horns, so every carpet has typical design motifs and I would liken those design motifs to a vocabulary, so that each carpet is telling a story and I’m moved by that story, it’s inexplicable; how can a person be moved by the story of designs on a carpet? I think these are mystical objects and I think that this is why they have such a high value. You told me the carpets that traditionally fetch the highest price per square foot are Azerbaijani.

R: That’s a fact, it’s backed up by auction records…. You can pick up any auction catalog and look through and you’ll see Azerbaijani carpet after Azerbaijani carpet.

J: But do they call them Azerbaijani carpets?

R: No, they do not, but again it’s also the French wine/European wine analogy.

J: I know you’ve changed your website to make that explanation; that 50 per cent of so-called Persian carpets were actually woven by Azerbaijani people.

R: It’s important to clarify that Persian carpets is such a large category, but when you speak specifically of NW Persia Serapi, Heriz, Hamadan, Bakhshaish, Tabriz, these regions, even though it is NW Persia, the people living there, the people who wove the carpets, who designed the carpets, are Azerbaijani.

J: When you show someone a carpet, what do you tell them about that?

R: In this case, that is a carpet made in Bakhshaish, which is an Azerbaijani design, and it is a real antique, that’s a masterpiece, at least 120 years old.

J: What happens when they weave a carpet like this now, how close can they get to the original?

R: You can get very close, but there are some things you can’t quite reproduce. Time has an effect on the materials that carpets are made from that can’t be replicated exactly. The dyes that color the wool were made using river water that contains certain minerals which affect the dyes that over time cannot be reproduced. But the high quality materials, craftsmanship and traditional design motifs of new carpets made in Azerbaijan make for a very beautiful and valuable carpet.

J: Does that mean in 100 years, these new carpets will become true antiques and not just some worn out old rug?

R: These high quality new carpets are the descendents of the original carpets, now antiques. We are not just copying old carpets, we are making new carpets in the traditional way.

J: It sounds like you are re-establishing an old tradition…

R: Yes, we are trying to re-establish this tradition with its long history of high quality….People who are interested in these fine old carpets, they know about Shirvan, Quba, places like that, but they don’t necessarily know these places are in Azerbaijan, populated by the Azerbaijanis who wove those fine carpets. I’ve been to these places and met with the weavers and when you see the pride they feel in their craft it touches your heart.

J: You told me you have some famous clients, what is their reaction when you tell them these are Azerbaijani carpets.

R: They are fascinated by that. Azerbaijani carpets are in museums and great collections all over the world and they need to know that they are buying into that kind of history.

J: How many times have you been to Azerbaijan, and what do you do when you are there, besides visit carpet factories and stores?

R: I’ve been there five times. I love it there, it’s an amazing country, I mingle with the people, they are lovable people. The food is the best. I love it there, I have very fond memories, it’s a magical place.

See http://www.richardrothstein.com for Richard’s stunning array of carpets and

http://www.richardrothstein.com/caucasian-rugs-persian-rugs.html for more on where they come from and who made them.

.jpg)