Pages 64-68

by Teymur Kerimli

Azerbaijan’s literature is a unique spiritual treasure-house for its people and there is no doubt that Nizami Ganjavi is one of the greatest representatives of this literary heritage. His works, with their unique poetic innovations and universal themes, have transcended borders to influence the literature of distant lands. We hope that by introducing readers to more detailed information about the great poet’s life and work, Nizami will be more appreciated in the West, too. Perhaps we can encourage more research in academic circles.

We will run a series of articles about Nizami by both Azerbaijani and international experts. The first article in the series deals with the poet’s creative environment and his ideas about the Azerbaijan- Turkish people. In the next issue we will introduce his Khamsa and other literary gems.

In reviewing world literature we see that two princi pal poets used the strong humanistic influence of art to rise above a cultural environment generally defined by the mysticism and prejudices of patriarchal feudalism. One of these was Nizami Ganjavi, the greatest representative of the Eastern Renaissance, who was born in the 12th century in Sunny Azerbaijan and represented the quintessence of world literature and philosophy in his immortal work Khamsa (Five) via the aesthetic power of his art. The other was William Shakespeare, the greatest representative of the Western Renaissance, who was born in Foggy Albion more than 400 years later to become a child of humanity. Even now, in times when science and technology are no longer developing in linear series but exponentially, we see how mysticism prevails proudly over healthy minds and it is impossible not to be amazed by the clear logic and consciousness in the works of these two brothers in art and intellect.

Nizami (his real name was Ilyas ibn Yusif) was not satisfied with just the deep intellect and poetic talent gifted by God. Throughout his lifetime he pursued knowledge diligently and doubled his experience with his poetic talent; these two great attributes contributed to his scientific and philosophical research into the happiness of the human being.

Nizami Ganjavi, who began by writing lyrics in short forms – gasida, gazal, rubai, soon compiled an anthology, Divan, and gained fame as a favourite and esteemed poet not only in the Near and Middle East, but also on distant shores. It is no accident that Muhammad Ovfi, who was engaged in literary activities in the palace of the Turkish sultan Eltutmush in Delhi, praised Nizami’s art in his narration Lubabul-elbab (The jewel of the select). The Indian poet Amir Khosrow Dehlevi (1253-1325) who lived a century after Nizami and who wrote his works in the Dari (middle Persian) language, as was traditional at that time and who was born into the Lachin family of Turks, was one of the first world-known poets to answer the Azerbaijani’s Khamsa.

The genius son of Azerbaijan, Nizami Ganjavi, shed the light of his creative synthesis of progressive humanist thought and inimitable poetic art across the world over the following centuries. Brought up in the environment of Ganja, which was a Near and Middle Eastern centre of science and culture of the in those times, this allowed the young Ilyas to study developments in science and philosophy.  Sultan Muhammad, the Khamsa of Nizami, British Library, Or. MS 2265, f.18r. Old Woman complaining to Sultan Sanjar. 1539-43, border replaced in the 17th C After devoting his youth to the study of sciences, he wrote his first poem when he was already 30 years old. He inscribed his name forever in the annals of art with his five poems, Treasury of Secrets (1175), Khosrow and Shirin (1180), Leyli and Majnun (1188), Seven Beauties (1197) and Iskander-Nameh (1203), presented to the world of literature over the next 30 years. They laid a strong foundation for the great Nizami school of literature which continues to exert its influence nowadays.

Sultan Muhammad, the Khamsa of Nizami, British Library, Or. MS 2265, f.18r. Old Woman complaining to Sultan Sanjar. 1539-43, border replaced in the 17th C After devoting his youth to the study of sciences, he wrote his first poem when he was already 30 years old. He inscribed his name forever in the annals of art with his five poems, Treasury of Secrets (1175), Khosrow and Shirin (1180), Leyli and Majnun (1188), Seven Beauties (1197) and Iskander-Nameh (1203), presented to the world of literature over the next 30 years. They laid a strong foundation for the great Nizami school of literature which continues to exert its influence nowadays.

Humanity is the motif at the very heart of Nizami’s poetry and the poet regarded it as his sacred mission to apply every ounce of creativity to the service of his people. In this lies the immortality and eternal youth of Nizami’s art through the centuries. His works have been translated into Western as well as into Eastern languages from time to time and played their role in humanity’s moral development.

Unfortunately, Nizami is still sometimes represented as an Iranian poet in certain academic circles, whether through ignorance or with deliberate intent. The best response to this is regular publication, popularization and translation of the works of the Azerbaijani genius by his own compatriots. It has to be said that no extensive research into Nizami’s work is being undertaken in countries like Iran.

There is convincing evidence to place the poet within Azerbaijani history: Both Nizami himself and all medieval sources which wrote about him confirm that he was born in 1141 in the city of Ganja, one of the ancient cultural centres of Azerbaijan and a capital of the Azerbaijani Atabeys’ state (1136- 1225); he lived and created in Azerbaijan throughout his life.

Byzantine, Georgian, Armenian and Arab historians confirm that Turks comprised the majority of the population living in Ganja city and its surroundings at least from the 5th century onwards and through Nizami’s lifetime. His poem Leyli and Majnun contains much autobiographical detail, including that his mother was a Kurdish woman, and in Seven Beauties he refers to himself as ikdish (this word is a pure Turkish word), in other words of mixed parentage:

Nizami ikdishe khalvatneshinast

Ke nime serke nime angabinast.

(Translation:

Nizami is an ikdish, sitting in a secret place He is half vinegar and half honey.)

By ‘vinegar’ Nizami means his Kurdish mother and ‘honey’ refers to his Turkish father. If his father had been Persian then a child born from his marriage to a Kurdish woman belonging to the same ethnic group could not have been considered ikdish (for example, a child born from the marriage of an Azerbaijani Turk to an Anadolu or Jigatay Turk is not considered ikdish). Moreover, the use of a Turkish word to express this concept underlines his ethnic origin.

Nizami saying Torkiyemra der in Hebesh ne khervend (Nobody sees my Turk origin) in another part of the poem again hints at his ethnic origin.

There is a concept of an Azerbaijani School of Poetry in medieval history and it implies the literature created in the Dari language on the territory of Azerbaijan during the 11th and 12th centuries. It is also known as sebke Azerbaijani (Azerbaijani style) in contemporary Iranian literature research, and international scientific workshops are held on this topic. This school, whose greatest representatives were the Azerbaijani poets Khagani Shirvani and Nizami Ganjavi, also gave world literature the poets Gatran Tabrizi, Falaki Shirvani, Mujiraddin Beylagani, Izaddin Shirvani and Givami Mutarrizi, all writing in the Dari languge.

There are many cases when, for different reasons, poets wrote in the official language of that region rather than their native tongue. As regards the Near and Middle East, Arabic was the sole literary language in the 7th-10th centuries, and Ibn al-Mugaffa, as-Saalibi, at-Tabari and many others who were ethnic Iranians wrote their works in Arabic. Also the Azerbaijani poets known under the name al-Azerbaijani at that time wrote in Arabic.

Thus it is wrong to call Nizami and other great representatives of the medieval Azerbaijan poetry school Iranian poets simply because they wrote in the Persian language. In the same way that the Iranian poets mentioned above, who wrote in Arabic, do not belong to Arabic literature.

Nizami’s whole creation is imbued with a love of Turks and of belonging to the Turks. Much research has been done on this, leaning heavily on the poet’s own works, and his Turkish origin has been proven. Many of his grandest images are those of Turks and others’ positive human features are compared with those of Turks.

The image of Shirin in the poem Khosrow and Shirin presents plenty of examples.

Some researchers into Nizami’s poetry have wrongly called Shirin an ‘Armenian princess’, as her aunt, Mahin Banoo was a ruler of the Arman state. The following arguments establish the true identities of Shirin and Mahin Banoo.

Mahin Banoo was the ruler not only of the Arman state, but also of the states of Arran, Mugan and Berda, all part of the present Republic of Azerbaijan, as well as the Abkhaz state, now part of Georgian territory. Arman was merely the mountainous part of this state, which was used as summer pasture.

The regions of Mahin Banoo’s state are described like this:

Nesheste khishra dar havayi

Be har fasli mohayya kerde jayi

Be fasla gol be Muganast jayash

Ke ta sarsabz bashad khake payash

Be tabestan shavad bar kuha Arman

Khoramad gol be gol kharman be kharman

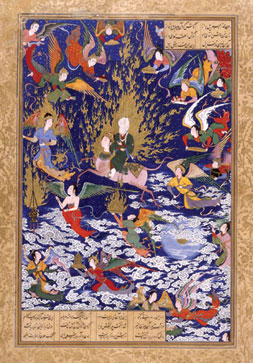

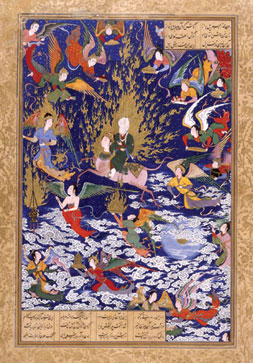

Tabriz, Iran, the Khamsa of Nizami, British Library, Or. MS 2265, f. 195. Muhammad’s ascent into heaven 1539–43 Be hengama khazan ayad be Abkhaz

Tabriz, Iran, the Khamsa of Nizami, British Library, Or. MS 2265, f. 195. Muhammad’s ascent into heaven 1539–43 Be hengama khazan ayad be Abkhaz

Koned bar gardana nakhjir parvaz

Zamestanesh be Berda meylchirest

Ke Berdara havaye garmsirast

Translation:

(Mahin Banoo) in every climate and in every season

Chooses a certain place for herself.

In the season of flowers she goes to Mugan

To set foot on the verdure

In summer she moves to the Arman mountains,

In autumn comes to Abkhaz

In winter prefers Berda (Khosrow and Shirin. Baku, 1981, p.63)

Arman is just the name of an area and has no direct connection with the Armenian ethnonym. The people who migrated to the territory of Arman and were known as the Armani, in other words those who live in Arman, actually call themselves Hay and their country Hayastan.

The word Arman is connected with the words rum and roman in Arabic.

In the poem Khosrow and Shirin, Nizami repeatedly calls Shirin and the people around her Turks. In part of the poem, Mahin Banoo, while instructing Shirin compares Khosrow with, the legendary Iranian ruler Keykhosrow, and themselves with Afrasiyab, the legendary Turk, leaving no room for doubt that both Mahin Banu and Shirin are Turks. The poet presents this argument on behalf of Mahin Banoo:

Gar u mahast ma niz afitabim,

Va gar keykhosrovast Afrasiyabim. (Khosrow and Shirin. p.63)

Translation:

If he (Khosrow – T.K.) is the Moon we are the Sun

And if he is Keykhosrow we are Afrasiyab

Nizami’s love for his native Turkish nation was so strong that even in the poem Leyli and Majnun, based on an Arab legend, he depicted Leyli and the beauties around her as Turks. In one part of the poem, while describing his female heroes, the poet writes:

Leyli went out of her apartment.

She was surrounded like a gem by a group

Of beauties with the honeyed li ps of her tribe.

They were called Turks who lived in Arabia (bold added –T.K.).

(Leyli and Majnun, p.96)

The love for the Turkish nation in the poet’s last works, Seven Beauties and Iskendername, is revealed overtly in the images of Fitna, Nushaba and a Chinese princess (in fact a Turkish princess) presented with great love for the Turkish image. Moreover, the poet calls his favourite hero, Iskender a Turk with the Rum (Roman) crown. In Seven Beauties, he calls himself Turk, a symbol of whiteness and purity, but the ignorant people around him are referred to metaphorically as black, Habashes (Ethiopians) he says Torkiyemra der in Hebesh ne khervend (Among the Habash, nobody sees my Turkish origin).

Nizami, who deals extensively with social motifs and political problems in the poem Treasury of Mysteries, cites an example of medieval Turkish state structure for the ruler of his time and writes:

Doulata torkan ke bolandi gereft

Mamlakat az dad pasandi gereft

Translation:

When the state of the Turks was rising

It was liked because of its just management.

Nizami who was not xenophobic, at the same time did not hide his love for Turks as his native people.

It has been definitively proved that the Qom version (the invented story of Nizami’s father migrating from the city of Qom in Iran to Ganja) which was interpolated into the poem Iskendername in the 18th century and does not exist in any of the reliable ancient manuscri pts of the Khamsa, is a complete fabrication and beneath criticism.

Thus, Nizami Ilyas ibn-Yūsuf known to the world by the name Ganjali (a resident of Ganja city) was born in Azerbaijan, was a son of the Azerbaijan land, named himself ikdish – as his mother was Kurdish and his father was Turkish, openly expressed his love for his native Turks in his works and distinctly reflected his pride in his ethnic origin.

In view of all the above and in spite of the fact that he wrote in the Dari language, we have every reason to recognize Nizami Ganjavi as an Azerbaijan poet, an ethnic Turk and an exponent of Turkish artistic and philosophical thought.

Nizami, the genius of Ganja is one of those rare representatives of world literature who were ahead of their time, whose main purpose in their life and work was to serve their people, defend them against oppression, injustice and harm and to implement their mission to the highest level.

About the author: Professor Teymur Kerimli is Deputy Director of Academic Studies at the Nizami Institute of Literature of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan and a Doctor of Philology.

He is an academic studying the art of Nizami and is a well-known Azerbaijani expert on medieval literature.

by Teymur Kerimli

Azerbaijan’s literature is a unique spiritual treasure-house for its people and there is no doubt that Nizami Ganjavi is one of the greatest representatives of this literary heritage. His works, with their unique poetic innovations and universal themes, have transcended borders to influence the literature of distant lands. We hope that by introducing readers to more detailed information about the great poet’s life and work, Nizami will be more appreciated in the West, too. Perhaps we can encourage more research in academic circles.

We will run a series of articles about Nizami by both Azerbaijani and international experts. The first article in the series deals with the poet’s creative environment and his ideas about the Azerbaijan- Turkish people. In the next issue we will introduce his Khamsa and other literary gems.

In reviewing world literature we see that two princi pal poets used the strong humanistic influence of art to rise above a cultural environment generally defined by the mysticism and prejudices of patriarchal feudalism. One of these was Nizami Ganjavi, the greatest representative of the Eastern Renaissance, who was born in the 12th century in Sunny Azerbaijan and represented the quintessence of world literature and philosophy in his immortal work Khamsa (Five) via the aesthetic power of his art. The other was William Shakespeare, the greatest representative of the Western Renaissance, who was born in Foggy Albion more than 400 years later to become a child of humanity. Even now, in times when science and technology are no longer developing in linear series but exponentially, we see how mysticism prevails proudly over healthy minds and it is impossible not to be amazed by the clear logic and consciousness in the works of these two brothers in art and intellect.

Nizami (his real name was Ilyas ibn Yusif) was not satisfied with just the deep intellect and poetic talent gifted by God. Throughout his lifetime he pursued knowledge diligently and doubled his experience with his poetic talent; these two great attributes contributed to his scientific and philosophical research into the happiness of the human being.

Nizami Ganjavi, who began by writing lyrics in short forms – gasida, gazal, rubai, soon compiled an anthology, Divan, and gained fame as a favourite and esteemed poet not only in the Near and Middle East, but also on distant shores. It is no accident that Muhammad Ovfi, who was engaged in literary activities in the palace of the Turkish sultan Eltutmush in Delhi, praised Nizami’s art in his narration Lubabul-elbab (The jewel of the select). The Indian poet Amir Khosrow Dehlevi (1253-1325) who lived a century after Nizami and who wrote his works in the Dari (middle Persian) language, as was traditional at that time and who was born into the Lachin family of Turks, was one of the first world-known poets to answer the Azerbaijani’s Khamsa.

The genius son of Azerbaijan, Nizami Ganjavi, shed the light of his creative synthesis of progressive humanist thought and inimitable poetic art across the world over the following centuries. Brought up in the environment of Ganja, which was a Near and Middle Eastern centre of science and culture of the in those times, this allowed the young Ilyas to study developments in science and philosophy.

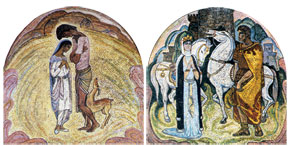

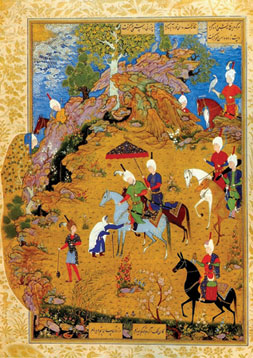

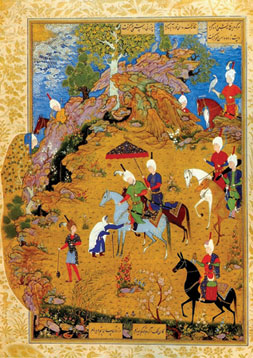

Sultan Muhammad, the Khamsa of Nizami, British Library, Or. MS 2265, f.18r. Old Woman complaining to Sultan Sanjar. 1539-43, border replaced in the 17th C

Sultan Muhammad, the Khamsa of Nizami, British Library, Or. MS 2265, f.18r. Old Woman complaining to Sultan Sanjar. 1539-43, border replaced in the 17th C Humanity is the motif at the very heart of Nizami’s poetry and the poet regarded it as his sacred mission to apply every ounce of creativity to the service of his people. In this lies the immortality and eternal youth of Nizami’s art through the centuries. His works have been translated into Western as well as into Eastern languages from time to time and played their role in humanity’s moral development.

Unfortunately, Nizami is still sometimes represented as an Iranian poet in certain academic circles, whether through ignorance or with deliberate intent. The best response to this is regular publication, popularization and translation of the works of the Azerbaijani genius by his own compatriots. It has to be said that no extensive research into Nizami’s work is being undertaken in countries like Iran.

There is convincing evidence to place the poet within Azerbaijani history: Both Nizami himself and all medieval sources which wrote about him confirm that he was born in 1141 in the city of Ganja, one of the ancient cultural centres of Azerbaijan and a capital of the Azerbaijani Atabeys’ state (1136- 1225); he lived and created in Azerbaijan throughout his life.

Byzantine, Georgian, Armenian and Arab historians confirm that Turks comprised the majority of the population living in Ganja city and its surroundings at least from the 5th century onwards and through Nizami’s lifetime. His poem Leyli and Majnun contains much autobiographical detail, including that his mother was a Kurdish woman, and in Seven Beauties he refers to himself as ikdish (this word is a pure Turkish word), in other words of mixed parentage:

Nizami ikdishe khalvatneshinast

Ke nime serke nime angabinast.

(Translation:

Nizami is an ikdish, sitting in a secret place He is half vinegar and half honey.)

By ‘vinegar’ Nizami means his Kurdish mother and ‘honey’ refers to his Turkish father. If his father had been Persian then a child born from his marriage to a Kurdish woman belonging to the same ethnic group could not have been considered ikdish (for example, a child born from the marriage of an Azerbaijani Turk to an Anadolu or Jigatay Turk is not considered ikdish). Moreover, the use of a Turkish word to express this concept underlines his ethnic origin.

Nizami saying Torkiyemra der in Hebesh ne khervend (Nobody sees my Turk origin) in another part of the poem again hints at his ethnic origin.

There is a concept of an Azerbaijani School of Poetry in medieval history and it implies the literature created in the Dari language on the territory of Azerbaijan during the 11th and 12th centuries. It is also known as sebke Azerbaijani (Azerbaijani style) in contemporary Iranian literature research, and international scientific workshops are held on this topic. This school, whose greatest representatives were the Azerbaijani poets Khagani Shirvani and Nizami Ganjavi, also gave world literature the poets Gatran Tabrizi, Falaki Shirvani, Mujiraddin Beylagani, Izaddin Shirvani and Givami Mutarrizi, all writing in the Dari languge.

There are many cases when, for different reasons, poets wrote in the official language of that region rather than their native tongue. As regards the Near and Middle East, Arabic was the sole literary language in the 7th-10th centuries, and Ibn al-Mugaffa, as-Saalibi, at-Tabari and many others who were ethnic Iranians wrote their works in Arabic. Also the Azerbaijani poets known under the name al-Azerbaijani at that time wrote in Arabic.

Thus it is wrong to call Nizami and other great representatives of the medieval Azerbaijan poetry school Iranian poets simply because they wrote in the Persian language. In the same way that the Iranian poets mentioned above, who wrote in Arabic, do not belong to Arabic literature.

Nizami’s whole creation is imbued with a love of Turks and of belonging to the Turks. Much research has been done on this, leaning heavily on the poet’s own works, and his Turkish origin has been proven. Many of his grandest images are those of Turks and others’ positive human features are compared with those of Turks.

The image of Shirin in the poem Khosrow and Shirin presents plenty of examples.

Some researchers into Nizami’s poetry have wrongly called Shirin an ‘Armenian princess’, as her aunt, Mahin Banoo was a ruler of the Arman state. The following arguments establish the true identities of Shirin and Mahin Banoo.

Mahin Banoo was the ruler not only of the Arman state, but also of the states of Arran, Mugan and Berda, all part of the present Republic of Azerbaijan, as well as the Abkhaz state, now part of Georgian territory. Arman was merely the mountainous part of this state, which was used as summer pasture.

The regions of Mahin Banoo’s state are described like this:

Nesheste khishra dar havayi

Be har fasli mohayya kerde jayi

Be fasla gol be Muganast jayash

Ke ta sarsabz bashad khake payash

Be tabestan shavad bar kuha Arman

Khoramad gol be gol kharman be kharman

Tabriz, Iran, the Khamsa of Nizami, British Library, Or. MS 2265, f. 195. Muhammad’s ascent into heaven 1539–43

Tabriz, Iran, the Khamsa of Nizami, British Library, Or. MS 2265, f. 195. Muhammad’s ascent into heaven 1539–43 Koned bar gardana nakhjir parvaz

Zamestanesh be Berda meylchirest

Ke Berdara havaye garmsirast

Translation:

(Mahin Banoo) in every climate and in every season

Chooses a certain place for herself.

In the season of flowers she goes to Mugan

To set foot on the verdure

In summer she moves to the Arman mountains,

In autumn comes to Abkhaz

In winter prefers Berda (Khosrow and Shirin. Baku, 1981, p.63)

Arman is just the name of an area and has no direct connection with the Armenian ethnonym. The people who migrated to the territory of Arman and were known as the Armani, in other words those who live in Arman, actually call themselves Hay and their country Hayastan.

The word Arman is connected with the words rum and roman in Arabic.

In the poem Khosrow and Shirin, Nizami repeatedly calls Shirin and the people around her Turks. In part of the poem, Mahin Banoo, while instructing Shirin compares Khosrow with, the legendary Iranian ruler Keykhosrow, and themselves with Afrasiyab, the legendary Turk, leaving no room for doubt that both Mahin Banu and Shirin are Turks. The poet presents this argument on behalf of Mahin Banoo:

Gar u mahast ma niz afitabim,

Va gar keykhosrovast Afrasiyabim. (Khosrow and Shirin. p.63)

Translation:

If he (Khosrow – T.K.) is the Moon we are the Sun

And if he is Keykhosrow we are Afrasiyab

Nizami’s love for his native Turkish nation was so strong that even in the poem Leyli and Majnun, based on an Arab legend, he depicted Leyli and the beauties around her as Turks. In one part of the poem, while describing his female heroes, the poet writes:

Leyli went out of her apartment.

She was surrounded like a gem by a group

Of beauties with the honeyed li ps of her tribe.

They were called Turks who lived in Arabia (bold added –T.K.).

(Leyli and Majnun, p.96)

The love for the Turkish nation in the poet’s last works, Seven Beauties and Iskendername, is revealed overtly in the images of Fitna, Nushaba and a Chinese princess (in fact a Turkish princess) presented with great love for the Turkish image. Moreover, the poet calls his favourite hero, Iskender a Turk with the Rum (Roman) crown. In Seven Beauties, he calls himself Turk, a symbol of whiteness and purity, but the ignorant people around him are referred to metaphorically as black, Habashes (Ethiopians) he says Torkiyemra der in Hebesh ne khervend (Among the Habash, nobody sees my Turkish origin).

Nizami, who deals extensively with social motifs and political problems in the poem Treasury of Mysteries, cites an example of medieval Turkish state structure for the ruler of his time and writes:

Doulata torkan ke bolandi gereft

Mamlakat az dad pasandi gereft

Translation:

When the state of the Turks was rising

It was liked because of its just management.

Nizami who was not xenophobic, at the same time did not hide his love for Turks as his native people.

It has been definitively proved that the Qom version (the invented story of Nizami’s father migrating from the city of Qom in Iran to Ganja) which was interpolated into the poem Iskendername in the 18th century and does not exist in any of the reliable ancient manuscri pts of the Khamsa, is a complete fabrication and beneath criticism.

Thus, Nizami Ilyas ibn-Yūsuf known to the world by the name Ganjali (a resident of Ganja city) was born in Azerbaijan, was a son of the Azerbaijan land, named himself ikdish – as his mother was Kurdish and his father was Turkish, openly expressed his love for his native Turks in his works and distinctly reflected his pride in his ethnic origin.

In view of all the above and in spite of the fact that he wrote in the Dari language, we have every reason to recognize Nizami Ganjavi as an Azerbaijan poet, an ethnic Turk and an exponent of Turkish artistic and philosophical thought.

Nizami, the genius of Ganja is one of those rare representatives of world literature who were ahead of their time, whose main purpose in their life and work was to serve their people, defend them against oppression, injustice and harm and to implement their mission to the highest level.

About the author: Professor Teymur Kerimli is Deputy Director of Academic Studies at the Nizami Institute of Literature of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan and a Doctor of Philology.

He is an academic studying the art of Nizami and is a well-known Azerbaijani expert on medieval literature.