Pages 88-93

by Aydin Kazimzade

Who was Mikhailo?

The Italian partisan leader Palmiro Togliatti went to Moscow in 1947 and met Stalin, leader of the USSR. During their conversation he mentioned the partisan Mikhailo, who had displayed great heroism in World War II, and he spoke of his incredible courage. But Mikhailo’s real identity as an Azerbaijani named Mehdi Huseynzade was not revealed during the conversation.

At the end of the 1940s, the State Security Commission (KGB) investigated the way people had fought in the war; who had avoided fighting, in what circumstances people had been captured or had gone over to the fascists, who had betrayed or served in German legions during 1941-1945.

At this time, i.e. in 1949, the head of the Yugoslav Communist Party, Josi p Broz Tito, also told Stalin about Mikhailo during a meeting. After this conversation, the fact that Mikhailo was Mehdi Huseynzade was revealed. Stalin ordered the State Security bodies to investigate the matter.

Investigating the archive documents…

Information about the heroism of Mehdi Huseynzade, who was a partisan during World War II, was filed under ‘Strictly Confidential’ in the archives. In the 12 page report, signed by the chairman of the Azerbaijan KGB on 29 November 1951, it was stated: “Huseynzade, Mehdi Hanafe oglu was born in Baku in 1918. His aunt brought up Mehdi and his sisters, who had lost their parents at a very early age. After Mehdi finished 7th grade he studied at the Baku Art School. He finished the school with high marks and went to Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) and wanted to continue his education at the Art Academy. But when that did not happen, he entered the French department of the Institute of Foreign Languages. In 1940, with financial problems, he left the 4th year of the course and returned to Baku, where he entered the 3rd year in the literature faculty of the Azerbaijani Pedagogical Institute.

After the Great Patriotic War (1941-1945 – ed.) began, Huseynzade was called up to the army and participated in the battle of Stalingrad as commanding officer of a mortar battery, having finished military school in Tbilisi. He was badly wounded in a battle in June 1942 and was captured by the Germans. He learned the German language while in captivity. He had only one goal then – to escape. When the Germans suggested that Mehdi study in the counter-espionage school, he agreed.

Events that followed show that Mehdi applied what he had learned at the school in operations against Hitler’s army, and his name became frenowned along the whole Adriatic coastline.

Mehdi and his friends, having escaped, joined the 9th Garibaldi Italian-Yugoslav partisan corps. They were active in operations against the fascist invaders from the outset. At the suggestion of corps headquarters, Mehdi was soon organizing a sabotage group. Using his fluency in German and knowledge of the fascist army`s methods, Huseynzade and his group mined railways, blew up German military formations and vehicles in the cities or caught and brought in informers. Sometimes, on assignment from corps headquarters, he executed traitors and Gestapo informers.

Huseynzade carried out his first big operation on 2 April 1944. He blew up a cinema near Trieste. As a result, 80 German soldiers and officers were killed and 110 were wounded. All night and the following day the Germans carried the dead and wounded soldiers and officers out of the ruins and took them away. A small obituary was published in the Italian fascist newspaper Il Piccolo.

In the same month Mehdi took on his second operation, probably the biggest in Trieste itself. The German Soldatenheim (soldiers’ house) was blown up and 450 soldiers and officers were killed or wounded.

After this attack, the Germans published a notice in their newspapers: “Whoever captures or kills the Russian partisan Huseynzade Mehdi, nicknamed ‘Mikhailo’, will receive a reward of 100,000 marks”.

Later, the more of Hitler’s followers that Mehdi destroyed, the more the Germans offered as a reward. The sum for capturing or killing Mikhailo was even increased to 300,000 marks.

In summer 1944, the Germans began more active operations against the partisans and prepared for a major attack. In order to discover the Germans’ plans and to organise counter-measures, the partisan corps headquarters needed an informer. This task was assigned to Mehdi: he was to find an informer and take him to headquarters.

Mehdi put on the uniform of a major in the German army, was supplied with the necessary documents and a vehicle and went to the city of Trieste with a fellow partisan. He stopped a German lieutenant near the headquarters of one of the military quarters in Trieste and asked him how to get to the right section. Saying he did not follow the officer’s directions, he asked him to get in the car so they could go together.

Mehdi took the officer to partisan headquarters. This informer was very valuable and gave useful information about the attack that was being prepared.

The third operation was to blow up the ‘Casino’ on Fortuna Street in Trieste. This was carried out in June 1944. Mehdi and his comrades entered the building wearing German uniforms and carrying bags full of explosives. They took off the uniforms in the wardrobe room and left the bags there. Then, saying they were going for cigarettes, they put on their hats and went out onto the street. 30 minutes later the ‘Casino’ blew up, 50 soldiers disappeared, together with the building, and there were many wounded.

As a rule, Mehdi would not go too far from the site being attacked. He wanted to see what happened with his own eyes and be sure that the assignment had been fulfilled. Several days later, a hotel which was a stopover for soldiers and officers passing through Trieste was destroyed by the saboteurs. Many fascists went to their graves under its ruins and 250 people were killed or wounded…”

Heroic in death

Other than this information in the report, the blowing up of the building where a German officer, Kartner, was working, Il Piccolo’s printing house, a German cinema at a place called Suzanna and other buildings were all associated with the name of brave Mehdi Huseynzade.

According to official information at the corps headquarters, as a result of sabotage operations carried out by Mehdi, more than 1,000 German soldiers and officers were killed or wounded in 9 months of 1944. All this was a small part of the dangerous work executed by the legendary Mikhailo – Mehdi Huseynzade.

With reference to the death of Mehdi Huseynzade, it is written: “When preparing for a battle in winter conditions, the corps headquarters assigned Mehdi and a group of partisans the task of obtaining clothes from German warehouses near the city of Gorica in October 1944.

This operation was not successful and the Germans pursued the partisans. The partisans could not shake them off and they had to spend the night in the village of Kras. But in the morning the Germans found them.

They pursued the partisans to the village of Vitovlje. And the tragedy happened there… When the Germans realised that the famous Mikhailo was among the partisans they blockaded the village, brought in artillery, assembled all the people and told them to show them the house where Mehdi was hiding. They said that otherwise they would burn the whole village and kill everybody, including the children and elderly.

The people stood in deathly silence looking down. Nobody pointed to the house where Mehdi was hiding. Then Hitler’s men began to shoot people in the square. They burned down a few houses. In order to save the village and innocent people Mehdi began firing with a submachine- gun, revealing himself.

The Germans surrounded the house and called on him to surrender. By way of an answer grenades began to rain down. Many soldiers were killed in this unequal battle. With his last bullet Mehdi Huseynzade, the partisan Mikhailo, put an end to his own life rather than surrender to the enemy.

The headquarters of the partisan corps, hearing about Huseynzade’s heroic death, sent a company of partisans from the Russian battalion to Vitovlje. They collected Mehdi’s body and returned it to the area under partisan control. He was buried in an appropriate way in a place called Chiapovano, where the corps headquarters was situated.”

Eventually, following extensive investigations and with the important facts revealed, on 11 April 1957 a decree of the USSR Higher Council Presidium declared Mehdi Huseynzade Hanifa oglu a Hero of the Soviet Union.

How ‘On a Distant Shore’ was made…

After the historical truth about Mehdi Huseynzade was revealed, steps were taken to immortalise his memory. Heydar Aliyev wrote in his memoirs: “… It was about the mid 1950s. The guys in Moscow didn’t want to accept the information about Mehdi Huseynzade being a traitor. The orders were to find enemies, to see who had served with the fascists in the legion. Nobody was looking for those who had displayed heroism on our side. The heroes behind enemy lines were revealed later. Note when the film The Seventeen Moments of Spring and other films were made! And when did we make the film On a Distant Shore? In 1958. At that time (in the early 1950s – A.K.) we collected materials about Mehdi and sent them to Moscow. When these materials were discovered we thought we should write an essay. We gave the materials to two or three of our employees to write it up. They began to write, but they were not professionals and nothing came of it. And so we handed over a lot of material about Mehdi Huseynzade to the Central Committee of the Azerbaijani Communist Party. We appealed for their help in writing it up as a literary piece”.

And this was what happened. The writers Imran Qasimov and Hasan Seyidbeyli wrote the novel On a Distant Shore about Mikhailo. And the director Tofiq Taghizade made a heroic-adventure film with the same name and based on the novel.

``The shore of the Adriatic Sea. The shore of a sea of harsh winds and severe storms. Now there are other storms on these distant shores. This severe storm has destroyed families and ruined homes. There is no sign of people in the city of Trieste, most have left their houses and gone to the mountains. Here they are. These courageous people don’t want the fascist invaders to walk their lands. There are Czechs and Bulgarians, Italians and Slovakians, Russians and Hungarians, French and Spanish. Even though they have different religions and traditions, one dream and one goal unites them all. One young man among them is Mehdi Huseynzade from Azerbaijan; he has come from the distant shore of the Caspian``.

The audience was riveted by this introduction and while seeing Mikhailo carrying out incredibly difficult operations with his friend Veselin, watching events unfold with rising excitement and hardly daring to blink. From the 1960s, ‘On a Distant Shore’ was one of the favourite films and the embodiment of courage for our youth. This work of art, summoning the youth to heroism, to defence of the motherland stands now as a real milestone in the history of Azerbaijani cinema.

There are several aspects to the success of films in the heroic-adventure genre. The first is that the hero must be sharp and credible; the actor must cut an attractive figure. The main job of the filmmakers is to create such a character. The actor creating Mehdi, Nodar Shashiqoghlu, showed that the war had separated a young artist, leading a quiet life, from his vocation and he became an experienced secret service officer. He understood that only with a gun was it possible to obtain peace and defend freedom.

The second task was to present the heroism of Mehdi Huseynzade, not in isolation from the people around him, but within the context of the whole struggle. The third was that the film emphasised Mehdi as an Azerbaijani among people of various nationalities and it created a national character.

…and its impact

The film of On a Distant Shore created huge resonance in the Soviet Union. It was awarded a diploma of encouragement (the jury could surely have given a higher award to such a film – A.K.) and the composer Gara Garayev received a second award for the soundtrack at the All-Union film festival held in Kiev in 1959. Huseynzade’s sister, Bike Alizade, wrote in her article A Feeling of Gratitude: “When watching the film On a Distant Shore, I saw how my brother fought with the enemy under fire, how he suffered in faraway lands during the great Patriotic War. My eyes were filled with tears. I felt as if I was watching the living Mehdi who had illumined our house with his sweet conversation and kind smile. I almost hugged and kissed him, grabbed his arm and took him home… When the film was over, the audience was talking about Mehdi’s heroism. At that moment my heart was beating with pride.”

The selection of actor Nodar Shashiqoghlu for the role of Mehdi ensured the film’s success. Director Tofiq Taghizade wrote: “…The correct allocation of roles and selection of artists was one of the main issues. The film’s hero had to be shown in several guises – a French artist, a German officer and a simple partisan, among others. We saw an actor who was able to create this complicated role in Nodar Shashiqoghlu, an actor from the Moscow State Drama and Comedy Theatre”.

In whatever city the film was shown, it was instantly popular with the audience. After its first screening at the International Film Festival in Tashkent in 1958, thousands of people waited for the actor and the director on the street. Bringing events which take place in foreign countries to the screen is hard work and requires deep understanding among the creative group. A certain knowledge is required to deliver a correct image of the cities which are the scene of the action. It was no easy matter to describe realistically the city of Trieste during World War II, the shores of the Adriatic Sea or the households and activity of the Yugoslavia-Italy union, the partisan movement, the climate of those distant times and the partisans’ struggle against the fascist invaders.

To achieve this, director Tofiq Taghizade and one of the scri ptwriters, Imran Qasimov, travelled to the places where the legendary hero had operated and they brought back many photographs. That is how they achieved a full and precise picture in the film. Director Taghizade and camera operator Alisattar Atakishiyev conveyed an internally holistic conception and maintained the visual structure of sequences and intonation in moving from one episode to another.

The princi ples behind the creation of a film-portrait and, particularly, Atakishiyev’s distinctive landscapes, are strongly apparent. The landscape is not there for the sake of beauty. It helps to reveal the character of the people who live in the mountains. The villagers who took food to the partisans knew that they could encounter danger at any time, but they still helped their fellow villagers, the partisans, and did not fear death.

The scenarios designed by production artists Jabrail Azimov and Kamil Najafzade completed the depiction of the partisans’ struggle against the fascists and the character of the hero. They were able to embody the faraway Italian land through the streets and mansions of Baku, Riga and the coast of Yalta. Thus the descri ptive language, settings and colour of the film are natural and real.

The music that Gara Garayev composed for the film has great emotional power. It is organically bound to the events portrayed and plays an important role in the unfolding of the film’s concept.

At the beginning of the film there is a flag with the fascist emblem. Fascists armed from head to toe pass confidently over a bridge in their jackboots. The music heard in these scenes shot from a low angle with strong light-shade contrast, heightens the audience’s feeling that Hitler’s soldiers bring death and destruction, that they have a harsh, savage nature.

The affecting power of music is also crucial to the final scene. The wounded Mehdi, in his last moments, remembers the Baku where he was born and brought up. A short, sad, lyrical melody is heard at this moment, as if reminding us that the hero’s dreams are incomplete. Thus, the interpretation of the final scene of the film has a psychological effect on the viewer: lyrical scenes of Azerbaijan are replaced by dramatic scenes – Mehdi’s heroic death. Composer Garayev also wrote interesting music for other episodes: Song of the Partisans, The Courage of Mehdi, Pursuit of Mehdi, The Scene between Mehdi and Angelica, Lyrical Stage, The Battle, Song about Baku, The Pursuit of Angelica etc. Leitmotifs connect all the musical scenes.

‘Nicknamed Mikhailo’ - Documentary Film

Tahir Aliyev, director of the Salname (chronicle) studio, has made a documentary film devoted to Hero of the Soviet Union Mehdi Huseynzade. It was shot in Austria, Slovenia and Italy. There are conversations with some of Mehdi’s fellow partisans, Angelica, who is familiar to the audience of the film On a Distant Shore, Angeli, the partisan girl who Mehdi truly loved (she is more than 80 years old now), the places where Mikhailo carried out operations – the bridges and the buildings and Mauthausen concentration camp where he was held captive.

When director Aliyev was in Slovenia he discovered new information about Mehdi Huseynzade’s death. He said: “The real name of Mehdi’s friend Veseli, familiar to the audience from the film On a Distant Shore, was Sar. When Mehdi was returning with him from an operation they hid in the roof of a two-storey house. Then they heard that the Germans had already attacked the village of Vitovlje and had started a search for Mikhailo. Mehdi and Sar were not expecting a battle with the Germans. When Mikhailo saw this he jumped from a window and was hit by a sniper’s bullet. Even though he was badly wounded, he was able to escape from the village, but he could not make it all the way back because he had lost too much blood. Mikhailo died there. The Germans were not able to find his body. A 12-year old girl found it. We have filmed that girl too. She found his body near a ditch in the village of Vitovlje and Mikhailo was buried right there. Three days later, Javad Hekimli told the partisans that it was impossible to keep Mikhailo’s body there and that the Germans were aware of his death. They took the body and buried him in the fraternal cemetery in the village of Chiapovano, 30 km away. His was the first grave in the cemetery. Mehdi Huseynzade passed away on 2 November 1944. The words `Mehdi-Mikhailo` were engraved on the monument over his grave.”

by Aydin Kazimzade

Who was Mikhailo?

The Italian partisan leader Palmiro Togliatti went to Moscow in 1947 and met Stalin, leader of the USSR. During their conversation he mentioned the partisan Mikhailo, who had displayed great heroism in World War II, and he spoke of his incredible courage. But Mikhailo’s real identity as an Azerbaijani named Mehdi Huseynzade was not revealed during the conversation.

At the end of the 1940s, the State Security Commission (KGB) investigated the way people had fought in the war; who had avoided fighting, in what circumstances people had been captured or had gone over to the fascists, who had betrayed or served in German legions during 1941-1945.

At this time, i.e. in 1949, the head of the Yugoslav Communist Party, Josi p Broz Tito, also told Stalin about Mikhailo during a meeting. After this conversation, the fact that Mikhailo was Mehdi Huseynzade was revealed. Stalin ordered the State Security bodies to investigate the matter.

Investigating the archive documents…

Information about the heroism of Mehdi Huseynzade, who was a partisan during World War II, was filed under ‘Strictly Confidential’ in the archives. In the 12 page report, signed by the chairman of the Azerbaijan KGB on 29 November 1951, it was stated: “Huseynzade, Mehdi Hanafe oglu was born in Baku in 1918. His aunt brought up Mehdi and his sisters, who had lost their parents at a very early age. After Mehdi finished 7th grade he studied at the Baku Art School. He finished the school with high marks and went to Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) and wanted to continue his education at the Art Academy. But when that did not happen, he entered the French department of the Institute of Foreign Languages. In 1940, with financial problems, he left the 4th year of the course and returned to Baku, where he entered the 3rd year in the literature faculty of the Azerbaijani Pedagogical Institute.

After the Great Patriotic War (1941-1945 – ed.) began, Huseynzade was called up to the army and participated in the battle of Stalingrad as commanding officer of a mortar battery, having finished military school in Tbilisi. He was badly wounded in a battle in June 1942 and was captured by the Germans. He learned the German language while in captivity. He had only one goal then – to escape. When the Germans suggested that Mehdi study in the counter-espionage school, he agreed.

Events that followed show that Mehdi applied what he had learned at the school in operations against Hitler’s army, and his name became frenowned along the whole Adriatic coastline.

Mehdi and his friends, having escaped, joined the 9th Garibaldi Italian-Yugoslav partisan corps. They were active in operations against the fascist invaders from the outset. At the suggestion of corps headquarters, Mehdi was soon organizing a sabotage group. Using his fluency in German and knowledge of the fascist army`s methods, Huseynzade and his group mined railways, blew up German military formations and vehicles in the cities or caught and brought in informers. Sometimes, on assignment from corps headquarters, he executed traitors and Gestapo informers.

Huseynzade carried out his first big operation on 2 April 1944. He blew up a cinema near Trieste. As a result, 80 German soldiers and officers were killed and 110 were wounded. All night and the following day the Germans carried the dead and wounded soldiers and officers out of the ruins and took them away. A small obituary was published in the Italian fascist newspaper Il Piccolo.

In the same month Mehdi took on his second operation, probably the biggest in Trieste itself. The German Soldatenheim (soldiers’ house) was blown up and 450 soldiers and officers were killed or wounded.

After this attack, the Germans published a notice in their newspapers: “Whoever captures or kills the Russian partisan Huseynzade Mehdi, nicknamed ‘Mikhailo’, will receive a reward of 100,000 marks”.

Later, the more of Hitler’s followers that Mehdi destroyed, the more the Germans offered as a reward. The sum for capturing or killing Mikhailo was even increased to 300,000 marks.

In summer 1944, the Germans began more active operations against the partisans and prepared for a major attack. In order to discover the Germans’ plans and to organise counter-measures, the partisan corps headquarters needed an informer. This task was assigned to Mehdi: he was to find an informer and take him to headquarters.

Mehdi put on the uniform of a major in the German army, was supplied with the necessary documents and a vehicle and went to the city of Trieste with a fellow partisan. He stopped a German lieutenant near the headquarters of one of the military quarters in Trieste and asked him how to get to the right section. Saying he did not follow the officer’s directions, he asked him to get in the car so they could go together.

Mehdi took the officer to partisan headquarters. This informer was very valuable and gave useful information about the attack that was being prepared.

The third operation was to blow up the ‘Casino’ on Fortuna Street in Trieste. This was carried out in June 1944. Mehdi and his comrades entered the building wearing German uniforms and carrying bags full of explosives. They took off the uniforms in the wardrobe room and left the bags there. Then, saying they were going for cigarettes, they put on their hats and went out onto the street. 30 minutes later the ‘Casino’ blew up, 50 soldiers disappeared, together with the building, and there were many wounded.

As a rule, Mehdi would not go too far from the site being attacked. He wanted to see what happened with his own eyes and be sure that the assignment had been fulfilled. Several days later, a hotel which was a stopover for soldiers and officers passing through Trieste was destroyed by the saboteurs. Many fascists went to their graves under its ruins and 250 people were killed or wounded…”

Heroic in death

Other than this information in the report, the blowing up of the building where a German officer, Kartner, was working, Il Piccolo’s printing house, a German cinema at a place called Suzanna and other buildings were all associated with the name of brave Mehdi Huseynzade.

According to official information at the corps headquarters, as a result of sabotage operations carried out by Mehdi, more than 1,000 German soldiers and officers were killed or wounded in 9 months of 1944. All this was a small part of the dangerous work executed by the legendary Mikhailo – Mehdi Huseynzade.

With reference to the death of Mehdi Huseynzade, it is written: “When preparing for a battle in winter conditions, the corps headquarters assigned Mehdi and a group of partisans the task of obtaining clothes from German warehouses near the city of Gorica in October 1944.

This operation was not successful and the Germans pursued the partisans. The partisans could not shake them off and they had to spend the night in the village of Kras. But in the morning the Germans found them.

They pursued the partisans to the village of Vitovlje. And the tragedy happened there… When the Germans realised that the famous Mikhailo was among the partisans they blockaded the village, brought in artillery, assembled all the people and told them to show them the house where Mehdi was hiding. They said that otherwise they would burn the whole village and kill everybody, including the children and elderly.

The people stood in deathly silence looking down. Nobody pointed to the house where Mehdi was hiding. Then Hitler’s men began to shoot people in the square. They burned down a few houses. In order to save the village and innocent people Mehdi began firing with a submachine- gun, revealing himself.

The Germans surrounded the house and called on him to surrender. By way of an answer grenades began to rain down. Many soldiers were killed in this unequal battle. With his last bullet Mehdi Huseynzade, the partisan Mikhailo, put an end to his own life rather than surrender to the enemy.

The headquarters of the partisan corps, hearing about Huseynzade’s heroic death, sent a company of partisans from the Russian battalion to Vitovlje. They collected Mehdi’s body and returned it to the area under partisan control. He was buried in an appropriate way in a place called Chiapovano, where the corps headquarters was situated.”

Eventually, following extensive investigations and with the important facts revealed, on 11 April 1957 a decree of the USSR Higher Council Presidium declared Mehdi Huseynzade Hanifa oglu a Hero of the Soviet Union.

How ‘On a Distant Shore’ was made…

After the historical truth about Mehdi Huseynzade was revealed, steps were taken to immortalise his memory. Heydar Aliyev wrote in his memoirs: “… It was about the mid 1950s. The guys in Moscow didn’t want to accept the information about Mehdi Huseynzade being a traitor. The orders were to find enemies, to see who had served with the fascists in the legion. Nobody was looking for those who had displayed heroism on our side. The heroes behind enemy lines were revealed later. Note when the film The Seventeen Moments of Spring and other films were made! And when did we make the film On a Distant Shore? In 1958. At that time (in the early 1950s – A.K.) we collected materials about Mehdi and sent them to Moscow. When these materials were discovered we thought we should write an essay. We gave the materials to two or three of our employees to write it up. They began to write, but they were not professionals and nothing came of it. And so we handed over a lot of material about Mehdi Huseynzade to the Central Committee of the Azerbaijani Communist Party. We appealed for their help in writing it up as a literary piece”.

And this was what happened. The writers Imran Qasimov and Hasan Seyidbeyli wrote the novel On a Distant Shore about Mikhailo. And the director Tofiq Taghizade made a heroic-adventure film with the same name and based on the novel.

``The shore of the Adriatic Sea. The shore of a sea of harsh winds and severe storms. Now there are other storms on these distant shores. This severe storm has destroyed families and ruined homes. There is no sign of people in the city of Trieste, most have left their houses and gone to the mountains. Here they are. These courageous people don’t want the fascist invaders to walk their lands. There are Czechs and Bulgarians, Italians and Slovakians, Russians and Hungarians, French and Spanish. Even though they have different religions and traditions, one dream and one goal unites them all. One young man among them is Mehdi Huseynzade from Azerbaijan; he has come from the distant shore of the Caspian``.

The audience was riveted by this introduction and while seeing Mikhailo carrying out incredibly difficult operations with his friend Veselin, watching events unfold with rising excitement and hardly daring to blink. From the 1960s, ‘On a Distant Shore’ was one of the favourite films and the embodiment of courage for our youth. This work of art, summoning the youth to heroism, to defence of the motherland stands now as a real milestone in the history of Azerbaijani cinema.

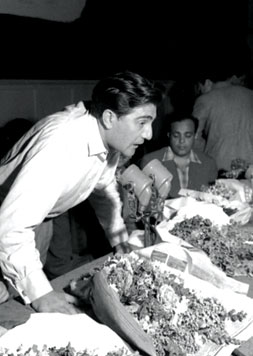

There are several aspects to the success of films in the heroic-adventure genre. The first is that the hero must be sharp and credible; the actor must cut an attractive figure. The main job of the filmmakers is to create such a character. The actor creating Mehdi, Nodar Shashiqoghlu, showed that the war had separated a young artist, leading a quiet life, from his vocation and he became an experienced secret service officer. He understood that only with a gun was it possible to obtain peace and defend freedom.

The second task was to present the heroism of Mehdi Huseynzade, not in isolation from the people around him, but within the context of the whole struggle. The third was that the film emphasised Mehdi as an Azerbaijani among people of various nationalities and it created a national character.

…and its impact

The film of On a Distant Shore created huge resonance in the Soviet Union. It was awarded a diploma of encouragement (the jury could surely have given a higher award to such a film – A.K.) and the composer Gara Garayev received a second award for the soundtrack at the All-Union film festival held in Kiev in 1959. Huseynzade’s sister, Bike Alizade, wrote in her article A Feeling of Gratitude: “When watching the film On a Distant Shore, I saw how my brother fought with the enemy under fire, how he suffered in faraway lands during the great Patriotic War. My eyes were filled with tears. I felt as if I was watching the living Mehdi who had illumined our house with his sweet conversation and kind smile. I almost hugged and kissed him, grabbed his arm and took him home… When the film was over, the audience was talking about Mehdi’s heroism. At that moment my heart was beating with pride.”

The selection of actor Nodar Shashiqoghlu for the role of Mehdi ensured the film’s success. Director Tofiq Taghizade wrote: “…The correct allocation of roles and selection of artists was one of the main issues. The film’s hero had to be shown in several guises – a French artist, a German officer and a simple partisan, among others. We saw an actor who was able to create this complicated role in Nodar Shashiqoghlu, an actor from the Moscow State Drama and Comedy Theatre”.

In whatever city the film was shown, it was instantly popular with the audience. After its first screening at the International Film Festival in Tashkent in 1958, thousands of people waited for the actor and the director on the street. Bringing events which take place in foreign countries to the screen is hard work and requires deep understanding among the creative group. A certain knowledge is required to deliver a correct image of the cities which are the scene of the action. It was no easy matter to describe realistically the city of Trieste during World War II, the shores of the Adriatic Sea or the households and activity of the Yugoslavia-Italy union, the partisan movement, the climate of those distant times and the partisans’ struggle against the fascist invaders.

To achieve this, director Tofiq Taghizade and one of the scri ptwriters, Imran Qasimov, travelled to the places where the legendary hero had operated and they brought back many photographs. That is how they achieved a full and precise picture in the film. Director Taghizade and camera operator Alisattar Atakishiyev conveyed an internally holistic conception and maintained the visual structure of sequences and intonation in moving from one episode to another.

The princi ples behind the creation of a film-portrait and, particularly, Atakishiyev’s distinctive landscapes, are strongly apparent. The landscape is not there for the sake of beauty. It helps to reveal the character of the people who live in the mountains. The villagers who took food to the partisans knew that they could encounter danger at any time, but they still helped their fellow villagers, the partisans, and did not fear death.

The scenarios designed by production artists Jabrail Azimov and Kamil Najafzade completed the depiction of the partisans’ struggle against the fascists and the character of the hero. They were able to embody the faraway Italian land through the streets and mansions of Baku, Riga and the coast of Yalta. Thus the descri ptive language, settings and colour of the film are natural and real.

The music that Gara Garayev composed for the film has great emotional power. It is organically bound to the events portrayed and plays an important role in the unfolding of the film’s concept.

At the beginning of the film there is a flag with the fascist emblem. Fascists armed from head to toe pass confidently over a bridge in their jackboots. The music heard in these scenes shot from a low angle with strong light-shade contrast, heightens the audience’s feeling that Hitler’s soldiers bring death and destruction, that they have a harsh, savage nature.

The affecting power of music is also crucial to the final scene. The wounded Mehdi, in his last moments, remembers the Baku where he was born and brought up. A short, sad, lyrical melody is heard at this moment, as if reminding us that the hero’s dreams are incomplete. Thus, the interpretation of the final scene of the film has a psychological effect on the viewer: lyrical scenes of Azerbaijan are replaced by dramatic scenes – Mehdi’s heroic death. Composer Garayev also wrote interesting music for other episodes: Song of the Partisans, The Courage of Mehdi, Pursuit of Mehdi, The Scene between Mehdi and Angelica, Lyrical Stage, The Battle, Song about Baku, The Pursuit of Angelica etc. Leitmotifs connect all the musical scenes.

‘Nicknamed Mikhailo’ - Documentary Film

Tahir Aliyev, director of the Salname (chronicle) studio, has made a documentary film devoted to Hero of the Soviet Union Mehdi Huseynzade. It was shot in Austria, Slovenia and Italy. There are conversations with some of Mehdi’s fellow partisans, Angelica, who is familiar to the audience of the film On a Distant Shore, Angeli, the partisan girl who Mehdi truly loved (she is more than 80 years old now), the places where Mikhailo carried out operations – the bridges and the buildings and Mauthausen concentration camp where he was held captive.

When director Aliyev was in Slovenia he discovered new information about Mehdi Huseynzade’s death. He said: “The real name of Mehdi’s friend Veseli, familiar to the audience from the film On a Distant Shore, was Sar. When Mehdi was returning with him from an operation they hid in the roof of a two-storey house. Then they heard that the Germans had already attacked the village of Vitovlje and had started a search for Mikhailo. Mehdi and Sar were not expecting a battle with the Germans. When Mikhailo saw this he jumped from a window and was hit by a sniper’s bullet. Even though he was badly wounded, he was able to escape from the village, but he could not make it all the way back because he had lost too much blood. Mikhailo died there. The Germans were not able to find his body. A 12-year old girl found it. We have filmed that girl too. She found his body near a ditch in the village of Vitovlje and Mikhailo was buried right there. Three days later, Javad Hekimli told the partisans that it was impossible to keep Mikhailo’s body there and that the Germans were aware of his death. They took the body and buried him in the fraternal cemetery in the village of Chiapovano, 30 km away. His was the first grave in the cemetery. Mehdi Huseynzade passed away on 2 November 1944. The words `Mehdi-Mikhailo` were engraved on the monument over his grave.”