Pages 64-67

Pages 64-67 By Turan Mammadaliyeva

The development of a jazz musician requires tremendous effort and sacrifice. As is the case with classical music, jazz, too, has its own history, stages of development and traditions. Since becoming part of this history in the 1930s, Azerbaijan’s jazz culture has travelled a long road and developed the most important jazz styles. Along with traditional jazz (classical swing and Dixieland), it has been enriched with elements of national music. As the Soviet jazz researcher Alexei Batashev said:

Jazz is a form of verbal culture. The musical language of jazz appears as a result of musical intercourse, and it is impossible to produce it without active exchange. This is particularly evident in Azerbaijan, a land of ancient musical traditions. This requires talented individuals working towards a common goal. [1, p. 291].

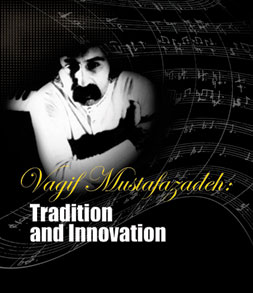

Working within Soviet culture, pioneers of Azerbaijani jazz Tofiq Guliyev, Parviz Rustambeyov, Rauf Hajiyev, Tofiq Ahmedov, Rafiq Babayev and Vagif Mustafazadeh happened to bear the lion’s share of that task. Although these outstanding musicians did not even constitute the greater part of Azerbaijani jazz in numerical terms, each one of them gave rise to an important trend or tradition in music. The personality of Vagif Mustafazadeh (1940-1979) has a very special niche within Azerbaijani jazz. He was the first to combine jazz with Azerbaijani mugham and is rightly acknowledged as the creator of a new musical style.

Jazz schools around the world have recognized Vagif as a phenomenal musician. His creations are of such interest because they represent a unique combination of eastern and western schools, of tradition and innovation. It is therefore appropriate to examine Mustafazadeh’s legacy in the overall cultural context.

Origins

Azerbaijani jazz emerged via many different routes. The first and perhaps the most important factor in laying the groundwork for a culture of jazz was the appearance of the variety show. The first professional composers to combine jazz, song and variety, Tofiq Guliyev and Rauf Hajiyev, developed a musical expression which incorporated urban songs and romances with sweet jazz. Another important source of models of intonation and harmony for national jazz was the musical language of professional composers, especially Fikret Amirov, Jovdat Hajiyev and Gara Garayev.

The third component in this foundation originated in national pianism [2, p. 20] and found its way into the works of a number of composers in the latter half of the last century. Vagif Mustafazadeh translated the qualities of national pianism harmoniously into the language of jazz.

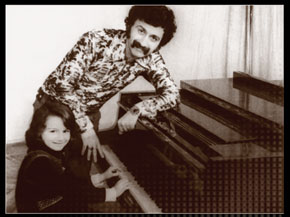

Mustafazadeh was born in Baku’s Old City on 16 March 1940. From his early years his phenomenal memory was exposed to Azerbaijani mugham and poems by Nizami, Fuzuli and Molla Panah Vagif. He was therefore destined to fall in love with music and to dedicate his whole life to it. He took his first piano lessons from Rebecca Levine at Music School No 1 and in 1958 he enrolled in Georgi Sharoyev’s class at the Asaf Zeynalli Music School. Despite entering the Azerbaijan State Conservatoire in 1964, his musical education ended in the same year. His technique and style of playing seemed strange to many and eventually cost him dear. Strange as it might seem, the young Vagif managed to master intuitively the traditions and knowledge necessary to become a jazz musician even without a higher education. The fact that an inclination towards national, especially mugham, music was instilled in him by his mother, Zivar Aliyeva, determined his interest in national pianism and urban folklore. This subconscious feel for mugham guided him throughout his career and had a great influence on his jazz musicianship.

The conventional education Mustafazadeh received at music school provided the foundation for a future as a pianist. European music traditions also contributed much to his creative work. While academic music was very significant in Mustafazadeh’s development as a musician and performer, it was also central to his melodic skills. Romantic composers influenced his emergence as an improviser.

Finally, the fact that he had studied various jazz styles and was so keenly interested in them set him on his lifelong path. In other words, Mustafazadeh capitalized on the knowledge he had gained from various sources, the communication with prominent musicians and the vibrant musical environment of his times, including various contests and festivals, to become a well-known composer and creator of a new style of jazz.

Jazz watershed

Unlike the early stages of jazz in Azerbaijan, the late 1950s and early 1960s were noted for the very knowledgeable and well-trained musicians, as well as the well-informed audience. This period is now seen as a watershed for all the former USSR’s jazz centres, especially in Moscow. Jazz was increasingly popular, thanks to technical progress. Jazz Hour, a programme broadcast on Voice of America and hosted by jazz expert and researcher Willis Conover, was a major source of in-depth information for US, European and other jazz fans. Such programmes gave most Soviet jazzmen in the 1950-60s the chance to listen to and record jazz compositions onto audio tapes; they soon became an important part of the education process. It was also in this period that cool-jazz, bebop, hard-bop and free-jazz emerged. John Coltrane’s modal-jazz, Bill Evans’s cool-jazz, fusion and other directions were the trends facilitating the development of modern jazz.

In the 1950s, these ideas inspired the work of German Lukyanov, Alexey Kozlov, Nikolay Levinovski and Leonid Chizhik in Russia, Uno Nayssoo, Lembit Saarsalu and Tino Nayssoo in Estonia, Vyacheslav Ganelin in Lithuania, Uldis Stabulnieks in Latvia, and Rafiq Babayev, Vagif Mustafazadeh and Vagif Sadigov in Baku. The latter three belonged to a generation of professional, educated, talented and experienced musicians. They adopted different styles of playing, eventually leading to a division of the jazz community into two camps – classical and modal jazz.

But it was Vagif Mustafazadeh who was destined to discover a completely new style within Azerbaijan’s music culture in the 1960s. With his colleague Rafiq Babayev, he was involved in three different aspects of jazz music – performing, orchestrating and composing. Vagif maintained this combination for the rest of his life. The modal style he applied to his compositions fitted very well into modern jazz trends.

The most important contributors to the formation of a jazz musician’s theoretical knowledge, practical skill and unique identity are music sessions, including daily rehearsal and live performances. The numerous jazz concerts and festivals organized to facilitate such an exchange were invaluable to jazzmen. It was at festivals that they asserted themselves and displayed their directions and interests. In the absence of a jazz school in the USSR, such exchanges of experience and ideas were the springboard for jazzmen. Mustafazadeh played festivals in Georgia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Russia, Poland and Monaco. But there were three landmark events in the moulding of his character. While sharing the stage with the best-known jazz musicians of the time in Tallinn in 1966, he encountered modal jazz and fusion as performed by Charles Lloyd and Keith Jarrett. During the Jazz-1978 festival in Tbilisi, which was joined by a number of prominent Soviet musicians, Mustafazadeh featured some compositions with the group Mugham group from a concept he had designed himself. Finally, the 1979 international jazz composition contest in Monaco was crucial in elevating his works to international level. Of all the anonymously-played compositions, Mustafazadeh’s Waiting for Aziza took the highest award.

The development of the Mustafazadeh style was influenced by musicians of various music genres: Bach, Mozart, Chopin, Ravel, Rachmaninov, Hajibeyov, Guliyev, Garayev, the jazzmen Charlie Parker, Bill Evans, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, McCoy Tyner and others. It was in their works that Mustafazadeh found and elaborated the music close to his own heart. Bill Evans enchanted him with his lyrical depth and romanticism. Romanticism and the lyrical were typical of Mustafazadeh, too, and manifested themselves in his love of his native country, city and people. In fact, these qualities were also characteristic of his close associate Tofiq Guliyev, whom he loved and communicated with frequently.

The most lyrical pianist

It was no coincidence that jazz critic Willis Conover described Mustafazadeh as the most lyrical pianist at the 1966 festival in Tallinn [3, p. 22]. His March, Native Nature, Evening Prelude and other compositions are vivid evidence of his lyrical nature. At the same time, the composer’s works were rich in non-lyrical reverie and even an anxiety that is difficult to comprehend. Profound, philosophical and somewhat sad emotions lay behind Vagif’s interest in John Coltrane’s works. 18th of the Month, Mugham and other compositions are quite typical of this mood. After mastering the mainstream styles of jazz, Vagif began using the folk-jazz (ethno-jazz) and fusion introduced by a number of outstanding jazzmen, including John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Chick Corea and others. In doing so, he developed so-called Mugham Jazz. With his ear for music and wonderful ability as a pianist, he made the best of his inimitable performing skills to produce a synthesis of jazz and mugham, both as a musician well-versed in the styles and as a jazzman applying the most modern musical techniques of his time.

One of the distinctive features of Mustafazadeh’s character was his good taste. Harmony was the most important component for him. This is very apparent in both the composer’s own creations and his improvisations on others’ works. Only listen to the most successful of his improvisations (including folk and composer tunes such as Black Mascara and Baku Nights, Zibeyda and The Ballad from his last album, also Joseph Kosma’s well-known Autumn Leaves) and his own compositions (March, The Moon, Mugham, Evening Prelude). Vagif was an unrivalled performer and interpreter of folk music and jazz composer; he created Azerbaijani jazz standards.

Jazz formed the core of Vagif Mustafazadeh’s legacy. There is plenty of literature listing his numerous jazz compositions, including fugues, preludes, ballads and scherzos; many written in the 1970s. He released a total of eight albums, all with different line-ups, mood and style. At the same time, they all bear the great musician’s hallmark. His early works, composed between 1971 and 1974, including The Caucasus, Spring and Improvisation, are written in the same tone system, have a clear melody and a precise form. The album released in 1975 reveals a more polished style. The 12 compositions on that album, especially March, Evening Prelude, Character and Sevil, are written in different tones and rhythms and provide different melodic solutions. The two albums released in 1979 represent the highpoint of Vagif’s style. They include the composer’s masterpieces Mugham, Waiting for Aziza, The Moon and Concert No 2.

Vagif Mustafazadeh’s works live on. A whole generation of young Azerbaijani musicians follows in his footsteps as well, of course, as the composer’s first daughter, pianist Lala Mustafazadeh, working at the Paris Conservatoire, and his other daughter, Aziza Mustafazadeh, who is often referred to in Europe as the princess of oriental jazz.

How can I wrap up my piece about one of the most outstanding personalities of Azerbaijani music? Vagif Mustafazadeh is the voice of Azerbaijani mugham reflected in jazz. There is much in common between the ancient mugham and modern jazz as discovered by Mustafazadeh. Both are forever mysterious and marvellous, both are capable of appealing to the human soul by stirring the most intimate of emotions and sentiments. Thus those still fond of Vagif Mustafazadeh’s music are also true devotees of Azerbaijani folk music.

References

1. Soviet jazz. Problems. Events. Masters (compiled by A. Medvedev, O. Medvedeva). Мoscow, 1987, p. 592, illustrated.

2. L. Rzayeva. The Pianism of Vagif Mustafazadeh / Materials of the First Republic Conference. Baku, 1992, p. 236.

3. R. Farhadov. Vagif Mustafazadeh. Baku, 1986, p. 85.

[Go to http://vagif.jazz.az/ choose a language version and then click on ‘music’ in the left-hand column to choose from a selection of Vagif Mustafazadeh’s music – ed.]