Pages 78-83

By Elchin Alibeyli

Azer Pasha Nematov is a creative, modern theatre director who has recently returned to the State Theatre for Young Audiences in Baku. Nematov has worked with both the Russian troupe (from the early 1970s) and the Azerbaijani (since 1983, when he was appointed Chief Director). His performances are noted for their contemporary language, innovation and modern aesthetic, notably in his directorial contributions to Alexander Ostrovsky’s “It’s a Family Affair” (1981), Kamal Aslan’s “It’s Hard to Be a God” (1982) and Rudyard Kipling’s “The Cat That Walked By Himself” (1983). He was awarded the Order of Glory by the President of Azerbaijan for his theatre work in 2007.

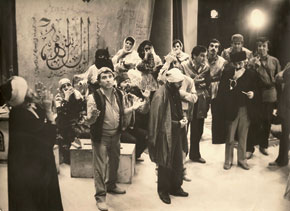

First play: The School in the Village of Danabash (1983 production)

Nematov’s first work with the Azerbaijani troupe was Jalil Mammadguluzade’s The School in the Village of Danabash (Danabash Kendinin Mektebi). The original play, written around 1920, is set in a small rural village panicked by the unexpected arrival of city officials. Things calm down when the villagers discover that the purpose of the visit is simply to open a school, but relationships sour once the Russified-Muslim teacher proves to be far less balanced and capable than hoped. Nematov’s production not only updated this anti-Tsarist satire, but also introduced colourful, contemporary styles of performance. Some claim that this production effectively laid the foundation for a new stage approach in Azerbaijani theatre, while actively preserving older national theatrical traditions.

The spirit and irony of Jalil Mammadguluzade’s original was preserved by mixing comedy, stage spectacle and traditional games that were both entertaining and thought provoking. The natural portrayal of ordinary folk was an important contribution to the play’s success. For local audiences this underlined the socio-political problems ridiculed in the theatre while confronting them with contemporary reality. Underlying the comedy were sharp representations of the contradictions, contrasts and zigzags in the characters’ natures at complex psychological moments.

The evening opened with the actors recalling memories of days gone by and relating their stories to each other as ordinary people with languorous humour, uniting storyteller, actor and audience. As illustrated and enlivened their stories, they fell into their different roles and changed into costume onstage. The wardrobe was itself onstage and the actors who were not involved in a scene would sit and watch the action as though part of the audience. This method, adapted from the practice of open-air theatre, added a defining sense of spectacle and conviction to the performance when applied within a modern theatre aesthetic.

The storyline was enhanced by the imagery on stage. Not by the exaggeration of scenes and characters, but by their apparent union. For example in the scene depicting the arrival of the Russian functionaries, the actors delivered a psychological expression of their characters’ bewilderment, worry and surprise – a sense of anxiety and expression - transmitted very effectively to the audience.

Naturally, a great director needs to work with fine actors. Aghakhan Salmanov (as Karbalayi Mirzali) and Nazim Ibrahimov (as Kablah Heydar) were amongst those who stood out for their ‘naturalness’ while Vahid Aliyev (as the translator) proved a comic hit. The staging included several novel and eccentric twists. The village houses in Danabash were presented as little boxes. The back curtain became an indicator of time passing, of enlightenment and spiritual growth – quite a theatrical achievement! A ploughing bull was represented by an actor wearing horns and this achieved an arresting rhythm and plasticity. The motion of the plough from one part of the stage to another was so realistic and surprising that the image really came to life for the audience. The whole was enlivened by a musical score by Javanshir Guliyev that was contemporary but inspired by folk music.

Nematov’s skilful direction made “The School in the Village of Danabash” not just a depiction of events from sometime in the Tsarist past. It bridged the past and present by drawing attention to the nation’s progress from ignorance to enlightenment. Nematov’s skilful direction produced a performance that was seen by some as an enlightened approach, helping to counteract the estrangement of local culture from its roots and morality by mass Sovietisation.

Second play: The Ascent of Mount Fuji

The Ascent of Mount Fuji (Voskhozhdenie na Fudziiamu) is a 1973 play by Kyrgyz author Chingiz Aitmatov, written with Kazakh bard Kaltai Mukhamedzhanov. When first published it was notable for its relatively open satire on the compromises of the Stalinist era. However, for a contemporary director, the slow moving piece can prove a challenge. Nematov’s approach was to elaborate on the authors’ examination of human relationships, moral feelings and sincerity, long since lost and replaced by affectation and cowardice. The central question posed is whether one is entitled to live by cheating on those closest to oneself for one’s own well-being. The authors want to reveal the characters’ true natures, but characters who have lost their true personal qualities and spiritual purity, cannot return to what they once were because insincerity has become too strongly ingrained and the spirit too distorted.

The story is if four childhood friends and their spouses who decide to go on a mountaineering trip to unwind, talk and escape their urban worries. Inspired by Japanese myths, they rename their Central Asian peak Mount Fuji, accepting Fuji as a symbol of spiritual purity, innocence and sanctity. Bowled over by the wonderful views, the group stops to prepare some food. And the talking begins.

In spite of years of friendship, an invisible curtain of deceit has fallen between the friends, preventing true relaxation or sincere discussion, an insincerity played up by Nematov’s stage direction. The friends’ aging former teacher, Aisha, appears and senses this vague aura of insincerity. She sits right in amongst them and begins interrogating and judging until they disclose all they have done in the many intervening years. The goal is to discharge their sins with the help of the purity associated with Fuji. The colourful if contradictory character of Aisha, herself, with her own deep psychological peculiarities, was drawn out in expert fashion in this production by venerable actress Firangiz Sharifova.

The friends began their psychologically revealing monologues; the direction and set design helping to establish a direct link to the audience. From the monologues, it becomes clear that the friends have morally betrayed their common friend Sabur, a talented poet who they regard as pessimistic and odd. They then begin condemning each other’s faults, blaming each other and trying to conceal their true intentions. Only one of the four (Mombet, brought to life by talented actor Firdovsi Naibov) wants to resolve the dilemma and get to the truth. He doesn’t flee, as his friends do, when informed of the death of a woman hit by a stone thrown from the mountain, but he stays to reveal the truth and responsibility; he is rejoined later by Dostobergen and Almagul (spouse of another of the friends). Almagul, played by Gulshan Gurbanova, seems not only to be a faithful wife, but also a seeker of the truth. She is the only one concerned about Sabur’s situation and his friends’ attitudes towards him. Almagul is also still on the mountain at the end of the play. Dostbergen, played by Mubariz Alikhanoglu, also wants to find the truth on Mount Fuji and, if necessary, answer for his actions.

Mombet cannot uncover the truth. Despite all their efforts, the friends, sitting together at the beginning of the play, drift apart as their relationships wither.

Aisha, left alone at the head of the table, senses the friends’ insincerity and walks away to return to her native village. By leaving them, she hopes that they will make true confessions without her. She no longer recognizes her formerly sincere and hard-working charges. The students she had seen off during the war, and for whom she waited to return alive, cannot now even be sincere with her. Nothing remains of their divine ideals. Those ideals have been replaced by masks; sculpted in hypocrisy, they have now become their faces.

After Aisha leaves, the atmosphere changes and the friends begin enjoying themselves as they had done before. Aggression vanishes. They begin to recall the old days. While talking about those days they throw stones over the edge. In the morning they get sad news: a woman passing by on the slopes below had fallen victim to one of those stones. They fall into arguing about whose stone had killed the woman. Sincerity disappears once more, with each character retreating behind his or her true ‘mask’. Throughout the play the lighting effects underlined not just changes of time, but also changes in the characters’ mood, adding further to a complex and thought provoking production.

Third play: "Slumber"

Kamal Aslan’s Slumber, devised from two novels, could be described as a slumber–fantasy. In this production, the director converted the sequence of dramatic events into a phased psychological state. Events and situations were conveyed as in a dream. The audience:

inevitably becomes first a passive witness, then an active participant in events which take place in an extraordinary place and time,

(Chingiz Alasgarov. Hope Doesn’t Disappear – Journal of Literature and Arts, date: 22.06.1990)

The state of slumber refers not only to the subconscious of the characters, but also the indolence enveloping society and a willing indifference to everything taking place. The differences between the inner worlds of the generalized characters Doctor and Patient, who have penetrated each other’s dreams, are conveyed in their dialogue. Patient is sick, not just physically, but also as a result of understanding the general reality and perceiving it as it is. Patient wants to switch the current and wake everyone up from their torpid state. Doctor is a generalised characterisation of authority. He displays complete indifference to Patient’s efforts and tries to keep everyone asleep.

Patient is not perfect either. He believes his ideals are worthy and exemplary, and he wants the whole of society to follow his way of thinking; there is no alternative to his views. Played by Logman Karimov, Patient after waking up, appears to be a populist, actively seeking a new order in life. His desire is explained by a wish to get back to a more ‘interesting’ life and to avoid reality. Doctor (Aghakhan Salmanov) is willing to wake from his slumber to go out to dinner parties and guest nights. When the sparring escalates between these two characters from opposite ends of the spectrum, a third person enters the fray. This is Human (played by Jafar Ahmadov), come to rescue those who wish to wake from slumber. Human is viewed differently by everyone, and cannot unite Doctor and Patient. Patient will not obey him, and seeks salvation in pain. Doctor, for his part, trusts Human, accepts absurdity as the sweetest reality and remains where he is. The first act ends here.

The second act also reveals an extraordinary situation. A woman who works an elevator (Firangiz Sharifova) complains, but still goes about her conventional, boring job. She only allows the elevator to be used to ascend to the upper floors, which seem to her to be a bolt-hole from reality. There is nothing for this woman beyond the world she perceives. For her the world starts with her and will end with her. This view is a thread running through the whole play.

The plot develops to reveal more of her character. As each victim is accompanied to the upper floors, her true face is exposed. Her coldness, expressed as an absence of love for anyone, even her own grandchild, is presented subtly via the character’s conduct and features. The aged woman sees everything as a dream. Sharifova skilfully conveys her character’s complex psychological moods.

As the performance moves on, another character appears – Grandchild, brought to life by Masuma Babayeva. The spark and sprightliness of this girl, who cannot understand her grandmother, creates an explicit contrast onstage, as in life itself. This extraordinary cycle of misunderstandings provides an obvious challenge to a director. Nematov underlines the key message with metaphors such as a door closing by itself, an elevator taking people up but not bringing them back down, and the moonlight. The stage, essentially, reflects the whole world and its collection of characters. A place which is visually small but representing borderless space.

About the author:Elchin Alibeyli was born in 1978 in the city of Yerevan. He has a master’s degree from Azerbaijan State University of Culture and Art and a postgraduate degree from the Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction. He is a Candidate of Art Criticism. He is the author of the book Azerbaijani Television, of the academic work The Search for Novelty on the Azerbaijani Stage and over 40 academic articles.

By Elchin Alibeyli

Azer Pasha Nematov is a creative, modern theatre director who has recently returned to the State Theatre for Young Audiences in Baku. Nematov has worked with both the Russian troupe (from the early 1970s) and the Azerbaijani (since 1983, when he was appointed Chief Director). His performances are noted for their contemporary language, innovation and modern aesthetic, notably in his directorial contributions to Alexander Ostrovsky’s “It’s a Family Affair” (1981), Kamal Aslan’s “It’s Hard to Be a God” (1982) and Rudyard Kipling’s “The Cat That Walked By Himself” (1983). He was awarded the Order of Glory by the President of Azerbaijan for his theatre work in 2007.

First play: The School in the Village of Danabash (1983 production)

Nematov’s first work with the Azerbaijani troupe was Jalil Mammadguluzade’s The School in the Village of Danabash (Danabash Kendinin Mektebi). The original play, written around 1920, is set in a small rural village panicked by the unexpected arrival of city officials. Things calm down when the villagers discover that the purpose of the visit is simply to open a school, but relationships sour once the Russified-Muslim teacher proves to be far less balanced and capable than hoped. Nematov’s production not only updated this anti-Tsarist satire, but also introduced colourful, contemporary styles of performance. Some claim that this production effectively laid the foundation for a new stage approach in Azerbaijani theatre, while actively preserving older national theatrical traditions.

The spirit and irony of Jalil Mammadguluzade’s original was preserved by mixing comedy, stage spectacle and traditional games that were both entertaining and thought provoking. The natural portrayal of ordinary folk was an important contribution to the play’s success. For local audiences this underlined the socio-political problems ridiculed in the theatre while confronting them with contemporary reality. Underlying the comedy were sharp representations of the contradictions, contrasts and zigzags in the characters’ natures at complex psychological moments.

The evening opened with the actors recalling memories of days gone by and relating their stories to each other as ordinary people with languorous humour, uniting storyteller, actor and audience. As illustrated and enlivened their stories, they fell into their different roles and changed into costume onstage. The wardrobe was itself onstage and the actors who were not involved in a scene would sit and watch the action as though part of the audience. This method, adapted from the practice of open-air theatre, added a defining sense of spectacle and conviction to the performance when applied within a modern theatre aesthetic.

The storyline was enhanced by the imagery on stage. Not by the exaggeration of scenes and characters, but by their apparent union. For example in the scene depicting the arrival of the Russian functionaries, the actors delivered a psychological expression of their characters’ bewilderment, worry and surprise – a sense of anxiety and expression - transmitted very effectively to the audience.

Naturally, a great director needs to work with fine actors. Aghakhan Salmanov (as Karbalayi Mirzali) and Nazim Ibrahimov (as Kablah Heydar) were amongst those who stood out for their ‘naturalness’ while Vahid Aliyev (as the translator) proved a comic hit. The staging included several novel and eccentric twists. The village houses in Danabash were presented as little boxes. The back curtain became an indicator of time passing, of enlightenment and spiritual growth – quite a theatrical achievement! A ploughing bull was represented by an actor wearing horns and this achieved an arresting rhythm and plasticity. The motion of the plough from one part of the stage to another was so realistic and surprising that the image really came to life for the audience. The whole was enlivened by a musical score by Javanshir Guliyev that was contemporary but inspired by folk music.

Nematov’s skilful direction made “The School in the Village of Danabash” not just a depiction of events from sometime in the Tsarist past. It bridged the past and present by drawing attention to the nation’s progress from ignorance to enlightenment. Nematov’s skilful direction produced a performance that was seen by some as an enlightened approach, helping to counteract the estrangement of local culture from its roots and morality by mass Sovietisation.

Second play: The Ascent of Mount Fuji

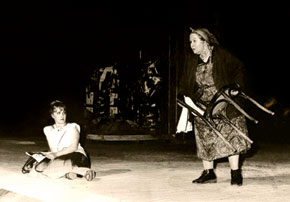

The Ascent of Mount Fuji (Voskhozhdenie na Fudziiamu) is a 1973 play by Kyrgyz author Chingiz Aitmatov, written with Kazakh bard Kaltai Mukhamedzhanov. When first published it was notable for its relatively open satire on the compromises of the Stalinist era. However, for a contemporary director, the slow moving piece can prove a challenge. Nematov’s approach was to elaborate on the authors’ examination of human relationships, moral feelings and sincerity, long since lost and replaced by affectation and cowardice. The central question posed is whether one is entitled to live by cheating on those closest to oneself for one’s own well-being. The authors want to reveal the characters’ true natures, but characters who have lost their true personal qualities and spiritual purity, cannot return to what they once were because insincerity has become too strongly ingrained and the spirit too distorted.

The story is if four childhood friends and their spouses who decide to go on a mountaineering trip to unwind, talk and escape their urban worries. Inspired by Japanese myths, they rename their Central Asian peak Mount Fuji, accepting Fuji as a symbol of spiritual purity, innocence and sanctity. Bowled over by the wonderful views, the group stops to prepare some food. And the talking begins.

In spite of years of friendship, an invisible curtain of deceit has fallen between the friends, preventing true relaxation or sincere discussion, an insincerity played up by Nematov’s stage direction. The friends’ aging former teacher, Aisha, appears and senses this vague aura of insincerity. She sits right in amongst them and begins interrogating and judging until they disclose all they have done in the many intervening years. The goal is to discharge their sins with the help of the purity associated with Fuji. The colourful if contradictory character of Aisha, herself, with her own deep psychological peculiarities, was drawn out in expert fashion in this production by venerable actress Firangiz Sharifova.

The friends began their psychologically revealing monologues; the direction and set design helping to establish a direct link to the audience. From the monologues, it becomes clear that the friends have morally betrayed their common friend Sabur, a talented poet who they regard as pessimistic and odd. They then begin condemning each other’s faults, blaming each other and trying to conceal their true intentions. Only one of the four (Mombet, brought to life by talented actor Firdovsi Naibov) wants to resolve the dilemma and get to the truth. He doesn’t flee, as his friends do, when informed of the death of a woman hit by a stone thrown from the mountain, but he stays to reveal the truth and responsibility; he is rejoined later by Dostobergen and Almagul (spouse of another of the friends). Almagul, played by Gulshan Gurbanova, seems not only to be a faithful wife, but also a seeker of the truth. She is the only one concerned about Sabur’s situation and his friends’ attitudes towards him. Almagul is also still on the mountain at the end of the play. Dostbergen, played by Mubariz Alikhanoglu, also wants to find the truth on Mount Fuji and, if necessary, answer for his actions.

Mombet cannot uncover the truth. Despite all their efforts, the friends, sitting together at the beginning of the play, drift apart as their relationships wither.

Aisha, left alone at the head of the table, senses the friends’ insincerity and walks away to return to her native village. By leaving them, she hopes that they will make true confessions without her. She no longer recognizes her formerly sincere and hard-working charges. The students she had seen off during the war, and for whom she waited to return alive, cannot now even be sincere with her. Nothing remains of their divine ideals. Those ideals have been replaced by masks; sculpted in hypocrisy, they have now become their faces.

After Aisha leaves, the atmosphere changes and the friends begin enjoying themselves as they had done before. Aggression vanishes. They begin to recall the old days. While talking about those days they throw stones over the edge. In the morning they get sad news: a woman passing by on the slopes below had fallen victim to one of those stones. They fall into arguing about whose stone had killed the woman. Sincerity disappears once more, with each character retreating behind his or her true ‘mask’. Throughout the play the lighting effects underlined not just changes of time, but also changes in the characters’ mood, adding further to a complex and thought provoking production.

Third play: "Slumber"

Kamal Aslan’s Slumber, devised from two novels, could be described as a slumber–fantasy. In this production, the director converted the sequence of dramatic events into a phased psychological state. Events and situations were conveyed as in a dream. The audience:

inevitably becomes first a passive witness, then an active participant in events which take place in an extraordinary place and time,

(Chingiz Alasgarov. Hope Doesn’t Disappear – Journal of Literature and Arts, date: 22.06.1990)

The state of slumber refers not only to the subconscious of the characters, but also the indolence enveloping society and a willing indifference to everything taking place. The differences between the inner worlds of the generalized characters Doctor and Patient, who have penetrated each other’s dreams, are conveyed in their dialogue. Patient is sick, not just physically, but also as a result of understanding the general reality and perceiving it as it is. Patient wants to switch the current and wake everyone up from their torpid state. Doctor is a generalised characterisation of authority. He displays complete indifference to Patient’s efforts and tries to keep everyone asleep.

Patient is not perfect either. He believes his ideals are worthy and exemplary, and he wants the whole of society to follow his way of thinking; there is no alternative to his views. Played by Logman Karimov, Patient after waking up, appears to be a populist, actively seeking a new order in life. His desire is explained by a wish to get back to a more ‘interesting’ life and to avoid reality. Doctor (Aghakhan Salmanov) is willing to wake from his slumber to go out to dinner parties and guest nights. When the sparring escalates between these two characters from opposite ends of the spectrum, a third person enters the fray. This is Human (played by Jafar Ahmadov), come to rescue those who wish to wake from slumber. Human is viewed differently by everyone, and cannot unite Doctor and Patient. Patient will not obey him, and seeks salvation in pain. Doctor, for his part, trusts Human, accepts absurdity as the sweetest reality and remains where he is. The first act ends here.

The second act also reveals an extraordinary situation. A woman who works an elevator (Firangiz Sharifova) complains, but still goes about her conventional, boring job. She only allows the elevator to be used to ascend to the upper floors, which seem to her to be a bolt-hole from reality. There is nothing for this woman beyond the world she perceives. For her the world starts with her and will end with her. This view is a thread running through the whole play.

The plot develops to reveal more of her character. As each victim is accompanied to the upper floors, her true face is exposed. Her coldness, expressed as an absence of love for anyone, even her own grandchild, is presented subtly via the character’s conduct and features. The aged woman sees everything as a dream. Sharifova skilfully conveys her character’s complex psychological moods.

As the performance moves on, another character appears – Grandchild, brought to life by Masuma Babayeva. The spark and sprightliness of this girl, who cannot understand her grandmother, creates an explicit contrast onstage, as in life itself. This extraordinary cycle of misunderstandings provides an obvious challenge to a director. Nematov underlines the key message with metaphors such as a door closing by itself, an elevator taking people up but not bringing them back down, and the moonlight. The stage, essentially, reflects the whole world and its collection of characters. A place which is visually small but representing borderless space.

About the author:Elchin Alibeyli was born in 1978 in the city of Yerevan. He has a master’s degree from Azerbaijan State University of Culture and Art and a postgraduate degree from the Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction. He is a Candidate of Art Criticism. He is the author of the book Azerbaijani Television, of the academic work The Search for Novelty on the Azerbaijani Stage and over 40 academic articles.