Carpet weaving and mugham music have been ambassadors across the globe for the rich culture of the Azerbaijani nation since the Middle Ages. Miniature art has joined them, and with good reason. There is now global interest in this art form. The fact that the artistic and literary traditions which have come down to us from ancient times are being continuously modernized and enriched is evidence enough. The unique form of miniature art has maintained its literary and aesthetic merit through the years.

A journey to the historical past

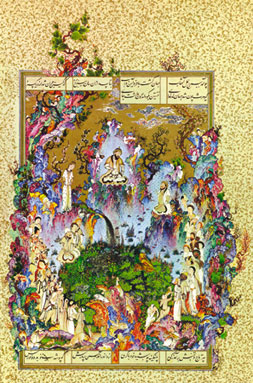

Azerbaijani miniatures date back to the medieval era when Islam was gaining ground in the country. The main stimulus was that graphic fine arts, the most common genre in Europe, were considered undesirable within the Islamic perspective. The Muslim, and Azerbaijani, painters who wished to create, were impelled to seek alternative forms of self expression. After long search, they came up with the wondrous and inconceivable, the occult, unearthly and soulful literary principles of miniature art. Those artists who contrived to express themselves in ornamental and symbolic colours and by infusing the particular dispositions, postures and gestures of their characters with meaning, declined the European approach and created a medium which is still often beyond one’s grasp. The best examples of medieval miniature art, still regarded as expressions of matchless skill, were created in Azerbaijan, in the city of Tabriz. The works of Sultan Muhammad are fine illustrations of the skills developed there. Judging from the examples still available, we can say that miniature art, which attained its initial literary-aesthetic heights in the 13th and 14th centuries, was flourishing in the 15th and 16th centuries. The art has, therefore, been very long-lived and is ingrained in every area of our traditional creativity. Nowadays, a museum which holds a single example of miniature art from Tabriz is well-respected; this fact alone demonstrates the great literary and aesthetic importance of the genre. Sad to say, more recent artistic trends have not developed the form. From the 18th century, the so-called Qajar style exerted a modernising influence on the artistic environment; it was based on the work of artists who had received an education in Europe and returned to Azerbaijan. This modernity entered the artistic pool and had some positive impact, still apparent. But the attitude towards miniature art has been cooling ever since.

Miniature art in the struggle against Soviet realism

After Azerbaijan’s annexation to the Soviet Union in 1920, attempts were made to force people to forget their traditional sources of pride. They were later pushed to extreme limits. In order to spread the ideology of communism, a series of artistic centres: the State Museum, School of Painting etc. were created in Baku in direct support of the socialist system. These measures on the one hand served to develop new, local painters, forming their aesthetic taste and world view; on the other hand, this education was remote from national literary roots and was based on Soviet-Russian principles of painting. Such well-organised politics soon bore fruit in all areas of the graphic arts. Within just ten years, any tendencies by young painters, graduates of the painting schools, to fall back upon national artistic traditions in works presented for exhibition were strongly criticized by the communist ideologists as being disposed towards bourgeois art. Any recourse to national artistic principles was held to be undesirable. Thus the socialist ideologists perverted their call for the principles of a ‘socialist regime’ to have socialist content but national shape and they built a barricade around the pursuits of creative artists. Nevertheless, many painters (Sattar Bahlulzade, Gazanfar Khaligov, Mikhail Abdullayev, Togrul Narimanbeyov etc.) recognized art as something that needed to extend beyond the scope of Soviet ideology and should serve the people. These artists created works which enriched the fine arts of Azerbaijan and brought them to international attention. One can sense the influence of miniature art in various of their works; sometimes clearly stated, sometimes in just a glimmer.

Since Azerbaijan regained its independence (1991) a series of attempts has been made to revive the miniature. Opening the Centre for the Miniature Art of Azerbaijan in the Old City, a division for book illustrations and miniature art at the Union of Artists, separate exhibitions of miniature art across the country, and the activities of the Peykar group of artists, have provided a stimulus for the revival and spread of classic traditions with new content.

The exhibitions From East to East – a call to appraise national traditions

With renewed independence, some artists believed that carpet-weaving and miniature art could form an international language for Azerbaijan within the art world. They believed that even though the modern trends seducing the world could be superficially attractive, they would gain neither domestic nor global recognition, being rooted rather in fashion than in national tradition. These artists, then, followed in the miniature tradition and represented the old artistic principles in new forms. They saw miniature art as the right form of artistic expression for themselves in the chaotic atmosphere then prevailing. Exhibitions of the resulting work proved their case. While only five artists (Altay Hajiyev, Rafis Ismayilov, Arif Huseynov, Nusrat Hajiyev and Orkhan Huseynov) represented the art in the first exhibition, From East to East, organized in 2008, twenty one artists of different ages presented their works in the following exhibition, held in 2010.

Works by People’s Artist Arif Huseynov have a considerable thematic range. In expressing his creative perception of folk tales, as mysterious as the art of miniature itself, of historical characters who are legendary symbols of morality, and of many other cultural landmarks, he comes up with dramatic and impressive images.

His series devoted to Azerbaijani folk tales and the Novruz holiday include The World of Uzeyir, Karabakh Shikestasi, Carpet Weaver etc. which are fine, attractive examples of the aesthetic presentation of cultural and moral values. Arif Huseynov’s miniatures extend beyond the borders of time and place, and certainly have a global, as well as domestic, appeal.

It is very natural to see People’s Artist Altay Hajiyev, who celebrates his 80th spring this year, among those working to give the miniature tradition a modern look. The son of a famous painter father, Amir, who also continued the traditions of miniature art, Altay has been prolific in his production of graphics and, more recently, paintings impregnated with national spirit. His linocuts include: Novruz Holiday and Ashugs, and paintings devoted to the poetic world of Khurshidbanu Natavan and to Nizami Ganjavi’s Khamsa. His use of the artistic principles of miniature art infuses tenderness and the miraculous into works with entirely different themes, even those with industrial motifs.

People’s Artist Rafis Ismayilov, better known to the Azerbaijani public for his cinema work, has a particular approach to miniature art. Strange though it might seem to modernise a miniature, Ismayilov’s modern miniatures, created with his cinematic eye, prove the possibility and success of such a transition. This is evident in his works devoted to the epic The Book of Dede Qorqud and Azerbaijani folk tales, rich in legendary motifs. As in classical miniatures, he conveys a plotline by the gestures of the characters in The Meeting and Thought.

Nusrat Hajiyev conveys his thoughts and ideas from the most outlandish forms and angles in his works devoted to folk tales of Azerbaijan, which are full of mystery. He is well known as an artist successfully mixing tradition with modernity. His interpretations of the folk tales Tapdiq, Bakhtiyar, Aygir Hasan and The PadShah Boy embody the charming and sweet frame of mind inherent in the literary material.

The late artists Sara Manafova (1932-2007) and Sanan Gurbanov (1938–1999) are remembered as artists with particularly creative approaches to the traditions of miniature art. Gurbanov focused on tenderness of line and striking rhythms. Manafova was more inclined to create a simple, bright mood.

Sirus Mirzazade and Elchin Aslanov, as well as Faiq Akberov, who is in continuous study of the miniature art, also tend to give a modern look to classic artistic traditions. Aslanov and Akbarov follow the traditions of miniature art and modernise its artistic interpretation, while Mirzazade does it by applying modern and attractive painting technique to images recalling miniatures.

Youth and rejuvenating calligraphy

Artists of the younger generations, too, look to miniature art for their motivation. Orkhan Huseynov’s City of Fairy Tales, with views of the Old City has become popular beyond our borders. He has a distinctively lyrical and poetic style new to Azerbaijani painting, as seen in his Father of the Nation, H. Z. Taghiyev. He bridges the distance to the capital’s ancient past by applying his creative interpretation to all that he has heard, read and seen.

Miniature art, from its first appearance, has run in parallel with calligraphy. From the Middle Ages onwards, calligraphic scripts, illustrated by wondrous miniatures, have been held in the treasuries of governors and monarchs.

Contemporary artists, recognising the role of Azerbaijani artists in the development of calligraphy, have tried to expand the borders of its expression. Among these are traditionalists (M.Azizov and T.Gorchiyev), as well as those improvising to achieve a unity of words and description (Azad Yashar and Yavar Asadov). The products of both styles are wondrous and fascinating.

Alongside the development of progressive artistic criteria and modern trends, it is absolutely necessary to preserve national features in determining the image of Azerbaijan’s fine arts. These features can be preserved only if artists have reference to ancient national traditions, give them new life and hand them on to the rising generations. As well as positively advancing their own creative images, this process has a huge role to play in determining the future image of Azerbaijani fine arts as a whole.

About the author: Ziyadkhan Aliyev is an Honoured Art Worker of the Azerbaijan Republic and the author of monographs and articles devoted to music, painting and other Azerbaijani arts.

A journey to the historical past

Azerbaijani miniatures date back to the medieval era when Islam was gaining ground in the country. The main stimulus was that graphic fine arts, the most common genre in Europe, were considered undesirable within the Islamic perspective. The Muslim, and Azerbaijani, painters who wished to create, were impelled to seek alternative forms of self expression. After long search, they came up with the wondrous and inconceivable, the occult, unearthly and soulful literary principles of miniature art. Those artists who contrived to express themselves in ornamental and symbolic colours and by infusing the particular dispositions, postures and gestures of their characters with meaning, declined the European approach and created a medium which is still often beyond one’s grasp. The best examples of medieval miniature art, still regarded as expressions of matchless skill, were created in Azerbaijan, in the city of Tabriz. The works of Sultan Muhammad are fine illustrations of the skills developed there. Judging from the examples still available, we can say that miniature art, which attained its initial literary-aesthetic heights in the 13th and 14th centuries, was flourishing in the 15th and 16th centuries. The art has, therefore, been very long-lived and is ingrained in every area of our traditional creativity. Nowadays, a museum which holds a single example of miniature art from Tabriz is well-respected; this fact alone demonstrates the great literary and aesthetic importance of the genre. Sad to say, more recent artistic trends have not developed the form. From the 18th century, the so-called Qajar style exerted a modernising influence on the artistic environment; it was based on the work of artists who had received an education in Europe and returned to Azerbaijan. This modernity entered the artistic pool and had some positive impact, still apparent. But the attitude towards miniature art has been cooling ever since.

Miniature art in the struggle against Soviet realism

After Azerbaijan’s annexation to the Soviet Union in 1920, attempts were made to force people to forget their traditional sources of pride. They were later pushed to extreme limits. In order to spread the ideology of communism, a series of artistic centres: the State Museum, School of Painting etc. were created in Baku in direct support of the socialist system. These measures on the one hand served to develop new, local painters, forming their aesthetic taste and world view; on the other hand, this education was remote from national literary roots and was based on Soviet-Russian principles of painting. Such well-organised politics soon bore fruit in all areas of the graphic arts. Within just ten years, any tendencies by young painters, graduates of the painting schools, to fall back upon national artistic traditions in works presented for exhibition were strongly criticized by the communist ideologists as being disposed towards bourgeois art. Any recourse to national artistic principles was held to be undesirable. Thus the socialist ideologists perverted their call for the principles of a ‘socialist regime’ to have socialist content but national shape and they built a barricade around the pursuits of creative artists. Nevertheless, many painters (Sattar Bahlulzade, Gazanfar Khaligov, Mikhail Abdullayev, Togrul Narimanbeyov etc.) recognized art as something that needed to extend beyond the scope of Soviet ideology and should serve the people. These artists created works which enriched the fine arts of Azerbaijan and brought them to international attention. One can sense the influence of miniature art in various of their works; sometimes clearly stated, sometimes in just a glimmer.

Since Azerbaijan regained its independence (1991) a series of attempts has been made to revive the miniature. Opening the Centre for the Miniature Art of Azerbaijan in the Old City, a division for book illustrations and miniature art at the Union of Artists, separate exhibitions of miniature art across the country, and the activities of the Peykar group of artists, have provided a stimulus for the revival and spread of classic traditions with new content.

The exhibitions From East to East – a call to appraise national traditions

With renewed independence, some artists believed that carpet-weaving and miniature art could form an international language for Azerbaijan within the art world. They believed that even though the modern trends seducing the world could be superficially attractive, they would gain neither domestic nor global recognition, being rooted rather in fashion than in national tradition. These artists, then, followed in the miniature tradition and represented the old artistic principles in new forms. They saw miniature art as the right form of artistic expression for themselves in the chaotic atmosphere then prevailing. Exhibitions of the resulting work proved their case. While only five artists (Altay Hajiyev, Rafis Ismayilov, Arif Huseynov, Nusrat Hajiyev and Orkhan Huseynov) represented the art in the first exhibition, From East to East, organized in 2008, twenty one artists of different ages presented their works in the following exhibition, held in 2010.

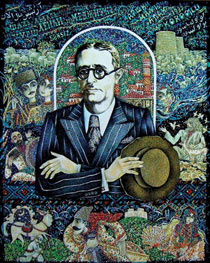

Works by People’s Artist Arif Huseynov have a considerable thematic range. In expressing his creative perception of folk tales, as mysterious as the art of miniature itself, of historical characters who are legendary symbols of morality, and of many other cultural landmarks, he comes up with dramatic and impressive images.

His series devoted to Azerbaijani folk tales and the Novruz holiday include The World of Uzeyir, Karabakh Shikestasi, Carpet Weaver etc. which are fine, attractive examples of the aesthetic presentation of cultural and moral values. Arif Huseynov’s miniatures extend beyond the borders of time and place, and certainly have a global, as well as domestic, appeal.

It is very natural to see People’s Artist Altay Hajiyev, who celebrates his 80th spring this year, among those working to give the miniature tradition a modern look. The son of a famous painter father, Amir, who also continued the traditions of miniature art, Altay has been prolific in his production of graphics and, more recently, paintings impregnated with national spirit. His linocuts include: Novruz Holiday and Ashugs, and paintings devoted to the poetic world of Khurshidbanu Natavan and to Nizami Ganjavi’s Khamsa. His use of the artistic principles of miniature art infuses tenderness and the miraculous into works with entirely different themes, even those with industrial motifs.

People’s Artist Rafis Ismayilov, better known to the Azerbaijani public for his cinema work, has a particular approach to miniature art. Strange though it might seem to modernise a miniature, Ismayilov’s modern miniatures, created with his cinematic eye, prove the possibility and success of such a transition. This is evident in his works devoted to the epic The Book of Dede Qorqud and Azerbaijani folk tales, rich in legendary motifs. As in classical miniatures, he conveys a plotline by the gestures of the characters in The Meeting and Thought.

Nusrat Hajiyev conveys his thoughts and ideas from the most outlandish forms and angles in his works devoted to folk tales of Azerbaijan, which are full of mystery. He is well known as an artist successfully mixing tradition with modernity. His interpretations of the folk tales Tapdiq, Bakhtiyar, Aygir Hasan and The PadShah Boy embody the charming and sweet frame of mind inherent in the literary material.

The late artists Sara Manafova (1932-2007) and Sanan Gurbanov (1938–1999) are remembered as artists with particularly creative approaches to the traditions of miniature art. Gurbanov focused on tenderness of line and striking rhythms. Manafova was more inclined to create a simple, bright mood.

Sirus Mirzazade and Elchin Aslanov, as well as Faiq Akberov, who is in continuous study of the miniature art, also tend to give a modern look to classic artistic traditions. Aslanov and Akbarov follow the traditions of miniature art and modernise its artistic interpretation, while Mirzazade does it by applying modern and attractive painting technique to images recalling miniatures.

Youth and rejuvenating calligraphy

Artists of the younger generations, too, look to miniature art for their motivation. Orkhan Huseynov’s City of Fairy Tales, with views of the Old City has become popular beyond our borders. He has a distinctively lyrical and poetic style new to Azerbaijani painting, as seen in his Father of the Nation, H. Z. Taghiyev. He bridges the distance to the capital’s ancient past by applying his creative interpretation to all that he has heard, read and seen.

Miniature art, from its first appearance, has run in parallel with calligraphy. From the Middle Ages onwards, calligraphic scripts, illustrated by wondrous miniatures, have been held in the treasuries of governors and monarchs.

Contemporary artists, recognising the role of Azerbaijani artists in the development of calligraphy, have tried to expand the borders of its expression. Among these are traditionalists (M.Azizov and T.Gorchiyev), as well as those improvising to achieve a unity of words and description (Azad Yashar and Yavar Asadov). The products of both styles are wondrous and fascinating.

Alongside the development of progressive artistic criteria and modern trends, it is absolutely necessary to preserve national features in determining the image of Azerbaijan’s fine arts. These features can be preserved only if artists have reference to ancient national traditions, give them new life and hand them on to the rising generations. As well as positively advancing their own creative images, this process has a huge role to play in determining the future image of Azerbaijani fine arts as a whole.

About the author: Ziyadkhan Aliyev is an Honoured Art Worker of the Azerbaijan Republic and the author of monographs and articles devoted to music, painting and other Azerbaijani arts.