Pages 34-38

Pages 34-38By Gulzada Abdulova

Karabakh has a long history as a centre of Azerbaijani arts and culture. Alongside the arts of stone dressing and metal working, weaving in the region also developed its own particular forms. The abundance of raw-materials, an important factor in the appearance and development of the craft, gave powerful impetus to its expansion. The devotion and expertise of the indigenous population to their art were especially apparent in their wool and silk weaving (galloon making).

The art of weaving can be traced back to the most ancient of days. Spindle heads obtained from archaeological sites of the Eneolith era indicate that ancient people living in the regions of Karabakh, Nakhchivan and Qazakh were engaged in the craft. Archaeological investigations carried out in the Karabakh region unearthed information about carpet weaving in Karabakh during the first Bronze Age. “Vessels with traces of weave found in barrows of the first Bronze Age, as well as spindle heads found at middle Bronze Age sites and hava (a tool used for carpet weaving) and other weaving tools discovered in Uzarliktepe also provide evidence”.1 Thus it seems clear that Karabakh developed as a centre of weaving in ancient times and was in at the origins of weaving in the Caucasus. Here the views of German explorer H. Ropers on Caucasian carpets are interesting. He noted that “Caucasian carpets were produced before those in Asia Minor and there is no doubt that the Caucasus is generally considered the homeland of oriental carpets. Thus woven artefacts, especially kilims (pileless rugs), were produced before fleecy carpets and they are currently produced mainly in the Caucasus”2.

It is a fact that Azerbaijani carpets comprise a large majority of Caucasian carpets. In this respect, and clarifying H. Ropers, it is possible to say that Azerbaijan, and especially Karabakh, is the homeland of the oriental carpet.

Karabakh carpets Europe

Their production techniques, variety of patterns and designs, diversity of colours and high styling made Karabakh carpets famous even in the Middle Ages. The epic Book of Dede Qorqud tells of thousands of silk carpets in the 7th century. The Arabian author Al-Mugaddasi, writing about the market in Berda city, noted that the carpets woven there had no equal3. Carpets of the Karabakh group were prominent among the Azerbaijani carpets exported to Europe from the 14th century and were well-known. Alongside other Azerbaijan carpets, those from Karabakh were prized by European painters as having great aesthetic value. We can see a Mugan carpet belonging to the Karabakh group in the pictures of Hans Memling Mary with the Child and Portrait of a Young Man. Carpets of the Tabriz and Shirvan (Shamakha) pattern, woven in the 16th century, along with a carpet called Goja (old man) woven in the 17th century in Karabakh, are displayed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Carpets from the Azerbaijani carpet centres Tabriz, Sheki, Shamakha, Ganja, Quba, Baku and Qazakh are held in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, the Louvre in Paris, metropolitan museums in Washington DC and in various museums and private collections in Vienna, Rome, Istanbul, Tehran and Cairo. Karabakh carpets have also graced art exhibitions in Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Petersburg and Moscow. In 1889 about 25 examples from the Shusha and Jabrail regions were displayed in a Caucasus exhibition. Muslim women from Shusha province demonstrated for visitors the process of weaving carpets on looms installed in the exhibition4.

Prior to occupation by the Russian Empire, merchants from Shamakha delivered carpets from Shirvan, Quba and Karabakh to Russia. Azerbaijani khans took carpet and rug products in lieu of taxes from their subjects; they were easily sold abroad or traded for other products5.

In the second half of the 19th century, carpet weaving became more widespread in the Shusha, Javanshir and Jabrail regions of Yelizavetpol (Ganja) province. In the 1890s, in just four regions of the province, about 100,000 people were engaged in carpet weaving6. The city of Shusha was the centre of the production and sale of Karabakh carpets. For comparison, we note that in Guba, the other carpet weaving art centre, only 30,000 people were involved7.

Writers of the late 19th century recorded that carpets and rugs woven in Shusha were regarded as the best in the whole Caucasus for their quantity and quality8.

Prestige

One reason for the extensive development of carpet weaving among other domestic crafts and the high value placed on its products, was the brisk demand for them to adorn homes, palaces and public buildings. Carpets were a symbol of wealth in the Karabakh region. It is true that mothers preparing to marry off their sons especially enquired about the weaving skills of prospective brides. According to custom, among the carpets and rugs in a girl’s dowry there had to be something she had woven herself. The Karabakh village of Khangervend’s carpet-based economy had a major impact on its social attitudes. It was noted that there the birth of a girl was a cause of greater joy than that of a boy. Each family wove one carpet per month. Homes without the sound of a loom were thought of as unlucky or poor and families celebrated carpet cutting (finishing) day9. The village girls were well-known for their application to their art, as well as for their diligence and skills. For this, if for no other reason, they had no shortage of suitors. There was no more valuable dowry than the carpet weaving skills of the girls of Khangervend. They learned the craft from six years old; it was a vocation for life and beyond; even after they had cut their last thread, their tools: hook, comb, scissors and loom, were engraved on their tombstones. Carpet and rug products were created by both nomadic and settled populations and almost all districts of the Karabakh region were producers, the exceptions being mainly villages in and around the mountains. Indeed it was the main field of employment among the cattle-breeding people of the lowland districts. According to sources from the late 19th century, it was said that “women in almost all Muslim families in the Aghdam community were engaged in carpet manufacturing”10.

Karabakh carpets were made in the districts of Shusha, Jabrail, Javanshir and Zengezur. Production here was more strongly developed than in other parts of the Southern Caucasus, both in volume and in diversity of design. One source said, “Carpet weaving in Shusha is seen as a domestic industry. The carpets are rarely woven to order. Everybody works for the free market. It is difficult to estimate the exact number of carpet masters; even the local district authority doesn’t know. It can only be said that the whole Muslim section of the city is engaged in the art.”11

Y. Zedgenidze, who carried out investigations in Karabakh in the 1890s, travelled the lands inch by inch and collected a wealth of information about carpet weaving. In his opinion the Karabakh masters of carpet weaving were Azerbaijanis. He wrote that very few Armenians were involved. Historical and everyday conditions also militated against the development of the art by Armenians: the art of weaving was passed to Muslims from Asia, thus Armenians were compelled to learn it from Azerbaijanis11.

Dyed in the wool excellence

As for the technical specificities of Karabakh carpets, motley and bright colours, botanical and zoomorphic images and portrait-style are characteristic properties. Their harmony of colour arose from a combination of taste, the artistic ideas of local masters and the vividness of the plants used to produce the dyes. Delicate but strongly woven carpets with a neatly trimmed surface, regular corners, unfading colours and woollen wefts were considered the best ones. Karabakh’s weavers were famous in their field for their matchless taste design, selection of ornamentation, symmetrical placement of paired elements and selvedge and dye making etc. By which they made unique decorative art works of their carpets. The carpet set (a carpet and accompanying side rugs) typical only of Karabakh among the Azerbaijani regions, is an especially notable seller. It consists of a central carpet, 4-8m long by 2m wide, and two side rugs, the same length as the central carpet and 1m wide (sometimes called kenare – edge rugs), head and bottom pieces were sometimes added.

The white-grey coloured wool of the Karabakh breed of sheep was very important in the development of the region’s carpet weaving. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, sheep farming in Karabakh leaped ahead of other regions. Naturally, the dyeing skills of local weavers contributed much to carpet quality. There is information that a whole hamlet in Karabakh was engaged in the dyeing craft. People went there from every quarter to dye their thread. In former times there was a dye-house in Jabrail district called chay yatagi (river-bed), in the Mammad bey kahriz (kahriz – underground water-supply).

Dyers had to have sharp eyes and be able to distinguish colours clearly. They had to know how to get the desired colour from plants and trees. The colours had to be permanent.

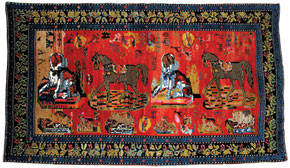

Peerless and pileless

Designs were passed on from neighbour to neighbour, even from village to village. As per custom, after cutting (finishing) a carpet, the owner of the design was given a ‘gift’. Sometimes there were weavers who made carpets freely from their own imagination, rather than from a pattern. Mohtaram Mammadova, Shakar Aliyeva, Telli khanim, the mother of Latif Karimov, the eminent carpet master, and scores of other masters and their works live on in the memory. Shakar Aliyeva, who spent more than a hundred years at the loom, wove carpets known by name: Itli-atli (with dogs and horses), Peleng (tiger), Buta (almond-shaped ‘paisley’ pattern), Gizilgul (Rose), Yaz chicheyi (Spring flower), Bahar (Spring) etc. It is notable that this skilful weaver, who could neither write nor read, wrote names on most of her carpets Mukhtar, Sadig, Asgar, Zarif, Hokuma and so on; she affixed her own signature (Sh) in all carpets and included dates.

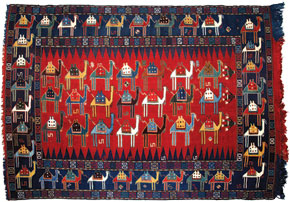

Pileless carpets were also a feature across the Karabakh region. They were generally referred to as palas, farmash, kilim etc. In spite of the fact that there were many different forms of pileless carpet products – mats, saddlebags, salt bags - the palas was especially significant. It is a thin, pileless mat, made quickly and cheaply for everyday heavy use, thus it was most profitable.12

Karabakh weavers were very experienced in weaving the more decorative, pileless kilim carpets. Traditional patterns and motifs in their kilims, and occasionally in piled carpets, included the apple, brick, hand, devil, chain, tray, bird, fish, horseshoe and buta. The verni is probably the most famous of the pileless carpets from Karabakh. No other carpet has patterns as striking as those of the verni. The dramatic ‘S’ shape and bird images resemble the patterns traced on metal and ceramic products of the first Bronze Age. This indicates that artistic imagination, mythic creativity and world view were transmitted from generation to generation, handed on to the weavers’ spiritual successors, even down to modern times.13 The main centres of verni production were Berda, the villages of Ashagi Seyidahmedli and Yukhari Seyidahmedli in Fuzuli district, the village of Lanbaran in Aghjabadi district, and Aghdam and Jabrail. When cattle-breeding families moved to the summer pastures in the mountains, they packed all their household goods into farmashes, loaded them onto their horses and camels and protected them with various coverlets. If these coverlets were vernis then the owner of the caravan was deemed to be a rich man. Verni carpets are woven with a winding technique and the pattern appears on both sides. This was probably why the verni was called “hamyan (two-sided)” in Karabakh, especially in Lanbaran village.

Karabakh carpets, which have wended their way down the millennia, are one branch of the Azerbaijan carpets now included in the UNICEF Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity; as integral to the family of carpets as Karabakh itself is to the country.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. H. F. Jafarov, Azerbaijan from the End of the 4th Millennium BC to the Beginning of the 1st Millennium BC (Baku, 2000) p.156

2. T. A. Bunyadov, The History of the Development of Weaving and Felting in Ancient Azerbaijan // Academy of Science (AS) of Azerbaijan, 1st issue, Baku: (AS publishing house, Azerbaijan SSR, 1964) pp.80-105

3. A. Gaziyev. Colour and Design in Azerbaijan Carpets.// Arts of Azerbaijan (Baku, 1949) pp.38-56.

4. Al-Mugaddasi. The Best Class for the Study of Climates in N.M. Valikhanli, Arab Geographer Travellers of the 9-12th Centuries on Azerbaijan, Elm (Science), (Baku, 1974) pp.129-134

5. M. Kh. Heydarov, The Cities and Urban Crafts of Azerbaijan from the 13th-17th centuries (AS publishing house, Azerbaijan SSR, 1982) p.200

6. A. S. Piralov. Brief Sketch of the Cottage Crafts of the Caucasus (Tbilisi 1900)

7. V.P.Gugushvili. The Industrial Development of Georgia and Transcaucasia vol.1 (AS publishing house, Georgian SSR, Tbilisi, 1957)

8. Azerbaijan History in three-volumes, vol. II (Baku, 1964)

9. Y. Zedgenidze, S. Zakharbekov, A.Ter-Yegiazarov, Yelizavetpol Province, Shusha City. in A Collection of Materials Describing the Districts and Tribes of the Caucasus (CMDDTC) (СМОМПК - Сборник материалов для описания местностей и племен Кавказа), 11th issue (Tbilisi: 1891)

10. L.G. Karimov, Azerbaijani Carpets vol. III (Baku, 1983)

11. A.S.Sumbatzade, Azerbaijani Agriculture in the 19th Century. (AS publishing house, Azerbaijan SSR Baku,1958)

12. B.I.Ibrahimbeyov, Shusha District, Aghdam Community in CMDDTC, 11th issue, 1st section (Tbilisi, 1891) 13. L.A.Karimov, Azerbaijani carpets, in Yazichi (Writer) (Baku, 1985)

About the author: Gulzada Abdulova is a PhD in History and ethnographer. She is the head of the Ethnography Foundation of the Azerbaijan National History Museum and is the author of research into the historical ethnography of Azerbaijan and carpet weaving.