Pages54-59

by Yagub Mahmudov

A letter from Elizabeth I to the Safavid Palace

England and Azerbaijan began their relationship during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603). There were six trade expeditions to Azerbaijan between 1561 and 1581 (this article is about the first three visits – ed.), English travellers covered every inch of our land and left behind much interesting information about it.

This initiative was no random exercise. The Safavid state (1501-1736), which enjoyed an increasing role and prestige in the international arena from the early 16th century onwards, also came to England’s notice, where capitalism was developing rapidly. The demand for markets for its famous cloth and the need for sources of cheap raw materials was rising continuously. However, England’s ships could reach neither the New World – America - ravaged by Spanish conquistadors at the time, nor could they enter a Mediterranean Sea dominated by Italian merchants. Moreover, the Portuguese controlled sea routes to India. In other words, the first stages of great geographical discovery were proving unfruitful for English capital. As it could not yet match its competitors in military-political conflict, it decided to strike a peaceful blow. English sailors tried to round the North Pole by probing north-west and north-east in search of a safer sea route to the East, particularly to India. However, the impassable glaciers of the Arctic Ocean proved to be even more dangerous…

...Finally, the idea of establishing direct contact with India across Russia, down the Volga-Caspian route and via Azerbaijan and Iran, appeared to offer the most promising potential.

This option was taken seriously. If it could be done, England would, first of all, strengthen its position with the Safavid state and establish trade relations with Azerbaijan, which was then a source of raw silk capable of meeting the demands of textile manufacturers; this would weaken trade relations between other western countries and Azerbaijan (via the Mediterranean and Black Seas) and thus English merchants would leapfrog the competition. Further, they could establish direct relations with India via the Safavid state, and would be in a position to capture the spice trade from the Portuguese. These then, were the real reasons for Queen Elizabeth’s 1561 appeal by letter to Shah Tahmasib (1524—1576). The English queen asked the Shah to decree privileges and immunities for an unlimited period for Anthony Jenkinson, leader of the first expedition to the Safavid state, and permission for his group to travel throughout the country with their goods, to stay wherever they wanted, for as long as they wanted and to conduct free trade without customs duties.

Passage to India

In her letter, written on 25 April 1561, Elizabeth I tried to convince Shah Tahmasib that Anglo-Safavid relationships would be advantageous for both parties:

If we could establish good relations between us, between our states and peoples, of good faith and of the sacred rights of hospitality and common good faith in human services, and they were protected and strictly observed, we hope that God the Almighty himself would help us to achieve great results in this small initiative for the sake of the great benefit of our peoples and for the sake of our honour and glory. (For documents on Anglo-Safavid relationships see: English Travellers in Moscow State in the 16th Century. Leningrad, 1937)

The real purpose of the English kingdom is also clear from other documents. For example, the Muscovy company, which had a monopoly on England’s trade relations with Russia, the Safavids and other neighbouring countries, in sending the first expedition to Azerbaijan, appointed Anthony Jenkinson to a special office on the eve of the trip on 8 May 1561. It is clear from this document that the English diplomat was to obtain a decree of permission from Shah Tahmasib to sell various English goods within the Safavid state and to buy any goods from there and take them to England. However, Jenkinson’s most important assignment was to work towards establishing relations with India. The company’s instructions were:

You should obtain a permanent guarantee of our free passage with goods through the territory of his (Shah Tahmasib’s) state to any part of India and other countries neighbouring Iran (ie. the Safavid state – Y.M.) and to return through there to Russia and other countries.

The First Visit: 1561-1563

In 1561, Anthony Jenkinson, an experienced sailor and diplomat, responsible to the management of the Muscovy company and accompanied by other of its employees, set out on his voyage from London to the Safavid Palace on a ship called ‘Swallow’. This voyage, first to Russian shores, pioneered England’s policy on Azerbaijan, neighbouring countries and India. The three-ship mission taking English merchants to Russia also carried 80 bales of cloth, valuable kitchen utensils, pearls, rubies and other precious stones. The cloth in particular was destined for sale on Safavid territory. The mission was also to stop off in Moscow to buy Russian goods, which sold well in Azerbaijan. Thus every care had been taken to ensure that this exploratory expedition would also make a profit. The Great Knyaz (Tsar) of Moscow Ivan IV (1533-1584) – also known as Ivan the Terrible - received Jenkinson on 15 March 1562. The traveller wrote that an envoy from Shirvan was also at the reception. Abdullah Khan, governor of Shirvan, (a region of Azerbaijan) had sent the diplomat to conduct negotiations with Ivan IV. Jenkinson recorded that he continued his voyage from Moscow with the envoy and that they:

became friends and talked a lot before reaching Astrakhan by sailing down the Volga.

Jenkinson had to stop in Astrakhan on company business, but the Azerbaijani messenger returned home on his own ship.

From Astrakhan the Swallow continued down the Volga and reached Shabran (northern Azerbaijan) on 6 August 1562. The English delegation took their merchandise from there to the city of Shamakha in Shirvan and Jenkinson was received on 20 August by Abdullah Khan, in fine style.

In my country you are a welcome visitor

On 6 October, he set off for Qazvin (now in northern Iran), the Safavid Palace, accompanied by his friend the Shirvan envoy. When he reached Qazvin, on 2 November, peace negotiations between Shah Tahmasib and the messenger of the Ottoman Sultan were in progress. Shah Tahmasib did not receive Elizabeth’s messenger until negotiations ended, on 20 November, with a fraternal treaty being concluded between the Safavid shah and the Ottoman sultan. Jenkinson’s reception, which followed, was not a happy one for the English diplomat. Having negotiated closer relations with the Ottoman Empire, the Safavid leader was not so well disposed to the English.

Jenkinson’s talks with Shah Tahmasib failed to fulfil the queen’s wishes, but he stayed on in Qazvin for a period, learning about the country’s trade, meeting Indian merchants and negotiating with them in trading spices. It is interesting that when Jenkinson mentioned the main cities of the extensive Safavid state, he noted Tabriz, Shamakha, Ardebil, Arash and others as important trading centres.

On 20 March 1563, having spent the whole winter in Qazvin, Jenkinson set off for Shirvan to return to his country. Shirvan’s governor again received him very well ,declaring that,

In my country you are a welcome visitor.

This kindness stemmed in part from Azerbaijan’s foreign trading position. After the Ottoman conquests, Azerbaijan had been prevented from trading in the Mediterranean and Black Seas and had no access to trade with the wider world than via the Caspian-Volga route. Raw silk exports, the mainstay of foreign trade, were key to economic revival. An opportunity to revive the silk traded opened up through relations with England.

The English traveller, so respectfully treated by the ‘king’ of Shirvan, stayed about a week in his residence, conducting negotiations which proved to be useful for England. By special decree, Abdullah Khan granted broad privileges to the English traders. The governor of Shirvan gave full liberty to these merchants... from London city of England… to trade safely on the territory of Shirvan, as they wished. In Shirvan, merchants of the Muscovy company...

…may conduct any buying and selling operations with cash or by means of exchange with our merchants or other people, may stay in our country as long as they wish and at any time may take their goods and leave the country without delay, restriction or obstacle.

Duty free

The English were also exempted from paying customs duties. State officials who violated this decree would be punished heavily:

Regardless of time, if any of our officials collecting customs duties, or other servants or any of them, infringe this order and create obstacles or afford any abuse, and require or force the abovementioned English merchants or any of them or their representatives to pay any fees or customs duties for any goods brought to our country or exported from here and if it is revealed: the abovementioned duty collectors and servants shall be dismissed and shall be subject to our rage. All the money and goods taken by them from the English merchants shall be returned.

Abdullah Khan’s decree also regulated palace trade:

Every time the mentioned English merchants or their representatives bring any goods useful for our treasury, the treasurer shall accept those goods and pay for these goods in cash or in exchange for the equivalent in raw silk.

The decree ended:

We require and order that when reading or showing this decree in any territory of the country, it shall be observed.

Jenkinson left Shamakha with these important trading privileges for England, following his negotiations with Shirvan’s governor. He took all the goods purchased to Shabran.

In April 1563, the English ship raised its anchor at Shabran and sailed for the Volga; it was loaded with raw silk, rare jewels and spices to sell in London and other English cities. By order of Ivan IV, Jenkinson took rare silk, jewels and other valuable goods for the Great Knyaz of Moscow. He wrote that on 20 August 1563 he submitted the jewels and silk bought in Azerbaijan to the treasury, and that his Majesty was very satisfied. Thus, the first, 1561—1563 trading expedition from England to Azerbaijan resulted in the establishment of trading relationships between the two countries. The groundwork for an English trading post had been done in Shamakha. The inflow to Shirvan of English merchants with broad trading privileges increased.

The Second Visit: 1563-1565

The English merchants made immediate use of these privileges. Jenkinson’s visit was not yet over when another ship belonging to the Muscovy Trading Company headed down the Volga River. The personnel on this ship, carrying various English goods to Azerbaijan, was led by Thomas Alcock, George Rain and Richard Cheney. Unlike Jenkinson and his colleagues, these English merchants came to Azerbaijan on a legal basis. While sailing south along the Volga they met Jenkinson on his way back from Azerbaijan, in April 1563, and received from him Abdullah Khan’s decree issuing the privileges to English merchants.

This trading expedition lasted from 1563—1565. We learn about the trip from a small diary kept by Richard Cheney which has survived to this day.

From the diary we know that the expedition, which departed from the English trading post in Yaroslavl on 10 May 1563, did not arrive at Azerbaijan’s Caspian shore until 11 August. The traveller wrote,

We arrived at our port in Media on 11 August.

It is interesting that although this English merchant was visiting the Land of Fire for the first time, unlike other travellers of those times he distinguished Azerbaijan from Iran, although wrongly calling it Media. By our port he meant Shabran. We know that one English ship had already pulled into Shabran and English sailors had entered its geographical coordinates on their maps.

Tented talks

The next information we have from Richard Cheney concerns Shamakha. The merchants had already moved their goods by caravan from the Caspian shore directly to Shamakha, which was a famous trading centre in that period. The information is also very brief; however, the Englishman describes the way of life of the time, particularly people’s hospitality. It is also evident that in the 16th century Russo-Azerbaijani trading relationships were expanding. Shortly before the English, Abdullah Khan had received Russian merchants. When the new guests – the English - entered the nomad tent, negotiations with the Russian merchants had been completed. Richard Cheney’s account is quite interesting:

On 21 August we reached Shamakha. Abdullah Khan’s camp consisted of nomad tents. These people received us very well. On the third day of our visit, we were invited to a reception by the king. We presented him with our gifts and he demonstrated respect... the king was sitting on the carpeted ground with legs crossed; all his courtiers were around him. There was a carpet on the ground, we were ordered to sit down, the king himself allocated everyone places to sit. He ordered the merchants of the Russian tsar to stand up and give us their places.

After the reception, the English merchants distributed the greater part of the goods they had brought to Shamakha between the courtiers. Thomas Alcock took the rest of the goods to Qazvin, and Richard Cheney stayed behind to collect the money for goods given on credit. While returning from trading in Qazvin, Alcock was killed in an accident. Cheney and other merchants were able to send the goods Alcock had purchased with the silk and other goods Cheney had bought in Shamakha to Russia.

The hopes that the English bourgeoisie had of Azerbaijan were coming to fruition. Richard Cheney wrote to the Muscovy Company, as he finalized the work of the expedition, advising that the expeditions continue. And here he gave his recommendation:

In order not to damage your honour and dignity, you should send wise and careful people to this country.

As we know, although these ‘wise and careful’ people were not able to strengthen their position in Azerbaijan, they did finally reach India via the sea route and colonized those ancient cultural lands.

The Third Visit: 1565-1567

Just three years had passed since the first English ship moored on the shore of the Caspian Sea on 6 August 1562. However, the advantages to England of the trade with Azerbaijan were obvious. The Muscovy company made a great profit from selling high quality raw silk, satin, brocade, gold lace and other rare and colourful silk cloth, jewels, spices and other eastern goods in London’s markets and endeavoured to expand trading relations with Azerbaijan. Thus, as soon as the second trading expedition (1563—1565) was complete, a third was immediately dispatched to the Caspian shore.

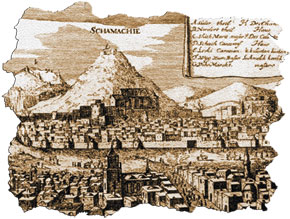

Shamakha ruler Abdulla khan receiving English voyager Anthony Jenkinson. artist, O. Sadiqzadeh. The Azerbaijan National History Museum

Shamakha ruler Abdulla khan receiving English voyager Anthony Jenkinson. artist, O. Sadiqzadeh. The Azerbaijan National History Museum

This trading mission was directed by Richard Johnson, Alexander Kitchin and

Arthur Edwards and lasted from 1565 - 1567. We have a great deal of useful historical information from materials connected with that expedition. Two letters sent by Arthur Edwards from Azerbaijan to England are particularly valuable; they were sent from Shamakha in 1566. The first was dated 26 April and the second was written on 8 August. I’d like to consider these valuable documents separately, revealing, as they do, the English merchant’s personal views. So, about the first letter…

When Arthur Edwards wrote his first letter, more than 7 months had passed since his arrival in Azerbaijan. He had been able to acquaint himself closely with trading life in Shamakha, the economy of the surrounding regions and generally with the Azerbaijani way of life. We may, therefore give credence to much of the information he gives.

It is clear from the opening that Anglo-Azerbaijani trading relationships were already being strengthened by Shirvan’s governor, Adbullah Khan. As before, he had received the merchants in person, proving that the decree issued to Anthony Jenkinson was still in force, and he had even ordered the preparation of:

a good house for the English merchants at any place in Shamakha that they would consider appropriate

in other words, he provided a separate building for the English trading post.

Edwards openly declared the English trading company’s real purpose regarding Azerbaijan - they planned to monopolize the raw silk trade:

I have no doubt that very soon we will become a big company in the trade of raw silk, silk cloth, spices and dyeing materials, as well as other goods here.

Other interesting information in this part of the letter is that the English merchants, besides the raw silk, spices, silk cloth, jewels and other valuable goods, were interested in dyeing materials. Azerbaijan, well-known for its colourful, richly-patterned carpets and silk cloth was also home to craftsmen who produced very clear dyes in rich and delicate shades. There was great demand for these dyes in England as production there increased.

Edwards also revealed that Russo-Azerbaijani relationships were developing well at that time. These relations had already expanded to the extent that Russian had become the language of discourse between local and English merchants. Russian merchants or other Russian speakers usually mediated in negotiations between English and Azerbaijani merchants.

England, Iberia, Italy…

We have interesting information about reciprocal relations between the Safavids and Spain and Portugal in the 16th century. Edwards wrote that they needed someone who spoke Portuguese, as well as a Russian speaker:

A person who can speak Portuguese (if we could find such person) could also benefit our company a lot.

Alum was another product that the foreign merchants bought from Azerbaijan. Edwards wrote that he had

prepared 223 batman of alum as a sample for sending to England

from Shamakha’s bazaars. This valuable mineral was also in demand at home for the production of leather goods, one of England’s traditional exports.

The English traveller mentions three Safavid cities, which comprised the heart of the country, and their population was more civilized. Two of them were the Azerbaijani cities of Tabriz and Ardebil. This information is valuable for research into the economic role of Azerbaijani cities within the Safavid state.

Edwards wrote an interesting recommendation to the management of the Muscovy company to ensure success in selling English goods in Azerbaijan

It is not worth sending your red London cloth. Red cloth with eastern prints dyed in Venice sell very well here...

This note is telling, not only because it indicates that the Venetians still dominated the English in competition for Azerbaijani markets, that there were ancient trading relations between Italy and Azerbaijan and that the Venetians profited from dying cloth with eastern patterns; it also indicates that the local population had exquisite taste.

At the end of his letter, Edwards provided a list of the goods that he advised should be taken from Azerbaijan to England and those that should be brought from England to Azerbaijan.

On 26 April 1566, immediately after sending his letter to the Muscovy company, Edwards went to the Safavid Palace in Qazvin and from 2-9 May 1566 he met the Safavid ruler Shah Tahmasib, conducting negotiations with him. Following the trip to Qazvin, he sent his second letter from Shamakha to England, on 8 August 1566.

This letter is even more interesting and valuable. In April, when he wrote his first letter, Edwards had seen only Shamakha and the surrounding regions, but by his second letter he had been to Qazvin, seen the southern parts of Azerbaijan and had gathered information about the Safavid state. He was familiar with both the country’s domestic life and its international trading relations. That is why in his second letter the traveller developed his initial considerations, clarified them and, most importantly, provided concrete information.

Breakthrough in Qazvin

It is clear from the second letter that Edwards’ negotiations with the Safavid ruler were successful; the Muscovy company had finally found the right approach. The merchant described the meeting:

On the 29th of the same month (May 1566 – Y.M) I appeared before him and I think we had about two hours of conversation. Twice he summoned me and asked if I had any requests. He listened to my requests and graciously promised that he would give me the documents I wanted. Later, he called me back twice more and asked questions about our kingdom, our country, about the goods we had and which goods we wished to buy here; he also asked questions about our neighbouring countries and the goods they had.

As we learn from the letter, the Shah’s benevolent reception and their two-hour conversation were not without reason. The Ottoman Empire and Portuguese had closed the Safavids’ access to the Mediterranean and Black Seas and to the Indian Ocean, the importance of the Volga-Caspian route for the state’s relations with the outside world and particularly for trading relations with England had greatly increased. When Shah Tahmasib understood which goods were of interest to the English merchants and which they wished to export from the Safavid state, he also expressed his thoughts about goods he wanted to be brought from England. Edwards wrote:

Afterwards, the Shah told me which of our goods he would like to purchase. At the end of the meeting, he said that Your Honour might send him any type of cloth. He immediately ordered his secretary to write down his wishes: three or four bales of each type of well-made, patterned London cloth as a sample.

The merchant also gave his views on which cloths would be particularly successful in the Safavid state.

On 29 May1566, during his negotiations with Shah Tahmasib, Edwards obtained a decree of privileges for the English merchants.

The Shah told me that if you do not like the documents you have received they can be changed in the future.

You want 100? – We’ll send 200!

From the letter it seems that the shah was not in a hurry to give a wide range of privileges to the English merchants, he wanted to see in practice how advantageous these new trading relations would be for his country. This is why he told the messenger from the English kingdom:

if your merchants have reasonable requests we will show mercy to them in the future.

The information given by the English traveller is most valuable in building a picture of the Safavids’ foreign trading opportunities. He wrote:

the Shah asked me if you can send him 100,000 bales of cloth per year. I answered that you can supply his country with 200,000 bales of cloth. His Majesty was very happy with that...

In this letter, Edwards showed that Azerbaijan kept trading relations with western countries, particularly with Venice, via Haleb (Aleppo, Syria); he listed the goods taken to that famous trading centre and wrote that raw silk was a means of exchange in trading relationships with western countries.

The English merchant suggested to local merchants in Shamakha that, instead of taking raw silk to Haleb, they could exchange it locally for English cloth. They agreed and even promised to supply the English merchants with spices. Here Edwards wrote: I have no doubt that we will gradually gain success in the spice and dye trades and this will be profitable.

When writing about the country’s foreign trading relations, Edwards, who stated that each year at least five or six thousands bales of wool cloth was imported from Haleb, did not forget ‘the main issue’, which was the silk trade. He detailed the foreign trade capacity of the Safavid state and did not believe that the English could purchase all the silk it exported.

Cash discount

The traveller returns to the question of purchasing ‘first hand’ silk. He wished to have extra money to buy silk from villagers at a low price. In this he envied the Turkish merchants, who were the main purchasers of Azerbaijani silk and England’s main rivals in trade:

Because they have cash, the Turks buy silk from the villagers at a low price as soon as they take it to market at the appropriate time of year.

The English merchant drafted a plan to supplant the Turkish merchants, not only in the silk trade, but in other areas, too. As mentioned above, Turkish merchants mainly offered silver for silk. There was great demand for silver in Azerbaijan because, besides the production of handicrafts, it was also used to produce money. This final element drew the Englishman’s attention. He wrote to London:

I would like you to send some silver in the form of bullion, to mint coins. The local governor would like it very much and it would be very profitable for us.

Thus, Azerbaijani governors and the Safavid ruler was looking for partners to bolster international trading relations and resolve problems of foreign policy, and they were applying to various countries, including European states.

Edwards wrote a third letter to England about his visit to the Safavid Palace. He wrote it in Astrakhan, while on his way back after completing his trip. In this document, written on 16 June 1567, he quoted from Shah Tahmasib’s decree afforded to the English merchants. He listed the privileges that represented initiatives by the Safavids, prevented from trading in the Mediterranean Sea, Black Sea and Indian Ocean, to export raw silk, which was the country’s main source of wealth, to Europe via trading relations with the English merchants.

Azerbaijani, language of diplomacy

According to Edwards’ notes, the Safavid governor had released merchants of the Muscovy company from customs duties and fees. The English also had permission to pass through the country to neighbouring states.

Shah Tahmasib had bestowed other privileges on the London merchants:

In all the cities where the English go and stay, the viceroys, local governors and court judges should take care of them, provide assistance, protect them from bad people, and punish any person who would harm them.

Edwards wrote:

After our goods have been transported to the seashore, with the help of God, the Shah’s servants should assist us in the transportation of these goods overland.

Further, those who took goods on credit and did not pay, bought goods without the merchant’s full consent, received gifts and even those who wanted to return goods they had purchased, would be punished.

After Edwards had listed these trading privileges, he wrote that the Safavid leader

…ordered his secretary to write the abovementioned articles (he meant the articles in the decree of privilege – Y. M.) into each of four letters. Then he gave these letters to me. At my request, two of them have been written in Turkish (ie. Azerbaijani – Y. M.) to send to you. On the back of one of the letters the secretary has written a list of goods that His Majesty would like to buy from you.

We think that this passage is very important as historical information, particularly for the history of our language. The fact that on 29 May 1566 the Safavid shah sent very important diplomatic documents from Qazvin to England written in Azerbaijani proves that the traditions set by Shah Ismail Khatai were still in place in the Safavid Palace and that Azerbaijani was the official language and the language of diplomatic correspondence.

About the Author: Yagub Mahmudov is Director of the History Institute of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences (ANAS)‚ professor and corresponding member of ANAS. He is a well-known specialist on medieval history. He is author of monographs and articles on issues relating to the history of Azerbaijan.

by Yagub Mahmudov

A letter from Elizabeth I to the Safavid Palace

England and Azerbaijan began their relationship during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603). There were six trade expeditions to Azerbaijan between 1561 and 1581 (this article is about the first three visits – ed.), English travellers covered every inch of our land and left behind much interesting information about it.

This initiative was no random exercise. The Safavid state (1501-1736), which enjoyed an increasing role and prestige in the international arena from the early 16th century onwards, also came to England’s notice, where capitalism was developing rapidly. The demand for markets for its famous cloth and the need for sources of cheap raw materials was rising continuously. However, England’s ships could reach neither the New World – America - ravaged by Spanish conquistadors at the time, nor could they enter a Mediterranean Sea dominated by Italian merchants. Moreover, the Portuguese controlled sea routes to India. In other words, the first stages of great geographical discovery were proving unfruitful for English capital. As it could not yet match its competitors in military-political conflict, it decided to strike a peaceful blow. English sailors tried to round the North Pole by probing north-west and north-east in search of a safer sea route to the East, particularly to India. However, the impassable glaciers of the Arctic Ocean proved to be even more dangerous…

...Finally, the idea of establishing direct contact with India across Russia, down the Volga-Caspian route and via Azerbaijan and Iran, appeared to offer the most promising potential.

This option was taken seriously. If it could be done, England would, first of all, strengthen its position with the Safavid state and establish trade relations with Azerbaijan, which was then a source of raw silk capable of meeting the demands of textile manufacturers; this would weaken trade relations between other western countries and Azerbaijan (via the Mediterranean and Black Seas) and thus English merchants would leapfrog the competition. Further, they could establish direct relations with India via the Safavid state, and would be in a position to capture the spice trade from the Portuguese. These then, were the real reasons for Queen Elizabeth’s 1561 appeal by letter to Shah Tahmasib (1524—1576). The English queen asked the Shah to decree privileges and immunities for an unlimited period for Anthony Jenkinson, leader of the first expedition to the Safavid state, and permission for his group to travel throughout the country with their goods, to stay wherever they wanted, for as long as they wanted and to conduct free trade without customs duties.

Passage to India

In her letter, written on 25 April 1561, Elizabeth I tried to convince Shah Tahmasib that Anglo-Safavid relationships would be advantageous for both parties:

If we could establish good relations between us, between our states and peoples, of good faith and of the sacred rights of hospitality and common good faith in human services, and they were protected and strictly observed, we hope that God the Almighty himself would help us to achieve great results in this small initiative for the sake of the great benefit of our peoples and for the sake of our honour and glory. (For documents on Anglo-Safavid relationships see: English Travellers in Moscow State in the 16th Century. Leningrad, 1937)

The real purpose of the English kingdom is also clear from other documents. For example, the Muscovy company, which had a monopoly on England’s trade relations with Russia, the Safavids and other neighbouring countries, in sending the first expedition to Azerbaijan, appointed Anthony Jenkinson to a special office on the eve of the trip on 8 May 1561. It is clear from this document that the English diplomat was to obtain a decree of permission from Shah Tahmasib to sell various English goods within the Safavid state and to buy any goods from there and take them to England. However, Jenkinson’s most important assignment was to work towards establishing relations with India. The company’s instructions were:

You should obtain a permanent guarantee of our free passage with goods through the territory of his (Shah Tahmasib’s) state to any part of India and other countries neighbouring Iran (ie. the Safavid state – Y.M.) and to return through there to Russia and other countries.

The First Visit: 1561-1563

In 1561, Anthony Jenkinson, an experienced sailor and diplomat, responsible to the management of the Muscovy company and accompanied by other of its employees, set out on his voyage from London to the Safavid Palace on a ship called ‘Swallow’. This voyage, first to Russian shores, pioneered England’s policy on Azerbaijan, neighbouring countries and India. The three-ship mission taking English merchants to Russia also carried 80 bales of cloth, valuable kitchen utensils, pearls, rubies and other precious stones. The cloth in particular was destined for sale on Safavid territory. The mission was also to stop off in Moscow to buy Russian goods, which sold well in Azerbaijan. Thus every care had been taken to ensure that this exploratory expedition would also make a profit. The Great Knyaz (Tsar) of Moscow Ivan IV (1533-1584) – also known as Ivan the Terrible - received Jenkinson on 15 March 1562. The traveller wrote that an envoy from Shirvan was also at the reception. Abdullah Khan, governor of Shirvan, (a region of Azerbaijan) had sent the diplomat to conduct negotiations with Ivan IV. Jenkinson recorded that he continued his voyage from Moscow with the envoy and that they:

became friends and talked a lot before reaching Astrakhan by sailing down the Volga.

Jenkinson had to stop in Astrakhan on company business, but the Azerbaijani messenger returned home on his own ship.

From Astrakhan the Swallow continued down the Volga and reached Shabran (northern Azerbaijan) on 6 August 1562. The English delegation took their merchandise from there to the city of Shamakha in Shirvan and Jenkinson was received on 20 August by Abdullah Khan, in fine style.

In my country you are a welcome visitor

On 6 October, he set off for Qazvin (now in northern Iran), the Safavid Palace, accompanied by his friend the Shirvan envoy. When he reached Qazvin, on 2 November, peace negotiations between Shah Tahmasib and the messenger of the Ottoman Sultan were in progress. Shah Tahmasib did not receive Elizabeth’s messenger until negotiations ended, on 20 November, with a fraternal treaty being concluded between the Safavid shah and the Ottoman sultan. Jenkinson’s reception, which followed, was not a happy one for the English diplomat. Having negotiated closer relations with the Ottoman Empire, the Safavid leader was not so well disposed to the English.

Jenkinson’s talks with Shah Tahmasib failed to fulfil the queen’s wishes, but he stayed on in Qazvin for a period, learning about the country’s trade, meeting Indian merchants and negotiating with them in trading spices. It is interesting that when Jenkinson mentioned the main cities of the extensive Safavid state, he noted Tabriz, Shamakha, Ardebil, Arash and others as important trading centres.

On 20 March 1563, having spent the whole winter in Qazvin, Jenkinson set off for Shirvan to return to his country. Shirvan’s governor again received him very well ,declaring that,

In my country you are a welcome visitor.

This kindness stemmed in part from Azerbaijan’s foreign trading position. After the Ottoman conquests, Azerbaijan had been prevented from trading in the Mediterranean and Black Seas and had no access to trade with the wider world than via the Caspian-Volga route. Raw silk exports, the mainstay of foreign trade, were key to economic revival. An opportunity to revive the silk traded opened up through relations with England.

The English traveller, so respectfully treated by the ‘king’ of Shirvan, stayed about a week in his residence, conducting negotiations which proved to be useful for England. By special decree, Abdullah Khan granted broad privileges to the English traders. The governor of Shirvan gave full liberty to these merchants... from London city of England… to trade safely on the territory of Shirvan, as they wished. In Shirvan, merchants of the Muscovy company...

…may conduct any buying and selling operations with cash or by means of exchange with our merchants or other people, may stay in our country as long as they wish and at any time may take their goods and leave the country without delay, restriction or obstacle.

Duty free

The English were also exempted from paying customs duties. State officials who violated this decree would be punished heavily:

Regardless of time, if any of our officials collecting customs duties, or other servants or any of them, infringe this order and create obstacles or afford any abuse, and require or force the abovementioned English merchants or any of them or their representatives to pay any fees or customs duties for any goods brought to our country or exported from here and if it is revealed: the abovementioned duty collectors and servants shall be dismissed and shall be subject to our rage. All the money and goods taken by them from the English merchants shall be returned.

Abdullah Khan’s decree also regulated palace trade:

Every time the mentioned English merchants or their representatives bring any goods useful for our treasury, the treasurer shall accept those goods and pay for these goods in cash or in exchange for the equivalent in raw silk.

The decree ended:

We require and order that when reading or showing this decree in any territory of the country, it shall be observed.

Jenkinson left Shamakha with these important trading privileges for England, following his negotiations with Shirvan’s governor. He took all the goods purchased to Shabran.

In April 1563, the English ship raised its anchor at Shabran and sailed for the Volga; it was loaded with raw silk, rare jewels and spices to sell in London and other English cities. By order of Ivan IV, Jenkinson took rare silk, jewels and other valuable goods for the Great Knyaz of Moscow. He wrote that on 20 August 1563 he submitted the jewels and silk bought in Azerbaijan to the treasury, and that his Majesty was very satisfied. Thus, the first, 1561—1563 trading expedition from England to Azerbaijan resulted in the establishment of trading relationships between the two countries. The groundwork for an English trading post had been done in Shamakha. The inflow to Shirvan of English merchants with broad trading privileges increased.

The Second Visit: 1563-1565

The English merchants made immediate use of these privileges. Jenkinson’s visit was not yet over when another ship belonging to the Muscovy Trading Company headed down the Volga River. The personnel on this ship, carrying various English goods to Azerbaijan, was led by Thomas Alcock, George Rain and Richard Cheney. Unlike Jenkinson and his colleagues, these English merchants came to Azerbaijan on a legal basis. While sailing south along the Volga they met Jenkinson on his way back from Azerbaijan, in April 1563, and received from him Abdullah Khan’s decree issuing the privileges to English merchants.

This trading expedition lasted from 1563—1565. We learn about the trip from a small diary kept by Richard Cheney which has survived to this day.

From the diary we know that the expedition, which departed from the English trading post in Yaroslavl on 10 May 1563, did not arrive at Azerbaijan’s Caspian shore until 11 August. The traveller wrote,

We arrived at our port in Media on 11 August.

It is interesting that although this English merchant was visiting the Land of Fire for the first time, unlike other travellers of those times he distinguished Azerbaijan from Iran, although wrongly calling it Media. By our port he meant Shabran. We know that one English ship had already pulled into Shabran and English sailors had entered its geographical coordinates on their maps.

Tented talks

The next information we have from Richard Cheney concerns Shamakha. The merchants had already moved their goods by caravan from the Caspian shore directly to Shamakha, which was a famous trading centre in that period. The information is also very brief; however, the Englishman describes the way of life of the time, particularly people’s hospitality. It is also evident that in the 16th century Russo-Azerbaijani trading relationships were expanding. Shortly before the English, Abdullah Khan had received Russian merchants. When the new guests – the English - entered the nomad tent, negotiations with the Russian merchants had been completed. Richard Cheney’s account is quite interesting:

On 21 August we reached Shamakha. Abdullah Khan’s camp consisted of nomad tents. These people received us very well. On the third day of our visit, we were invited to a reception by the king. We presented him with our gifts and he demonstrated respect... the king was sitting on the carpeted ground with legs crossed; all his courtiers were around him. There was a carpet on the ground, we were ordered to sit down, the king himself allocated everyone places to sit. He ordered the merchants of the Russian tsar to stand up and give us their places.

After the reception, the English merchants distributed the greater part of the goods they had brought to Shamakha between the courtiers. Thomas Alcock took the rest of the goods to Qazvin, and Richard Cheney stayed behind to collect the money for goods given on credit. While returning from trading in Qazvin, Alcock was killed in an accident. Cheney and other merchants were able to send the goods Alcock had purchased with the silk and other goods Cheney had bought in Shamakha to Russia.

The hopes that the English bourgeoisie had of Azerbaijan were coming to fruition. Richard Cheney wrote to the Muscovy Company, as he finalized the work of the expedition, advising that the expeditions continue. And here he gave his recommendation:

In order not to damage your honour and dignity, you should send wise and careful people to this country.

As we know, although these ‘wise and careful’ people were not able to strengthen their position in Azerbaijan, they did finally reach India via the sea route and colonized those ancient cultural lands.

The Third Visit: 1565-1567

Just three years had passed since the first English ship moored on the shore of the Caspian Sea on 6 August 1562. However, the advantages to England of the trade with Azerbaijan were obvious. The Muscovy company made a great profit from selling high quality raw silk, satin, brocade, gold lace and other rare and colourful silk cloth, jewels, spices and other eastern goods in London’s markets and endeavoured to expand trading relations with Azerbaijan. Thus, as soon as the second trading expedition (1563—1565) was complete, a third was immediately dispatched to the Caspian shore.

Shamakha ruler Abdulla khan receiving English voyager Anthony Jenkinson. artist, O. Sadiqzadeh. The Azerbaijan National History Museum

Shamakha ruler Abdulla khan receiving English voyager Anthony Jenkinson. artist, O. Sadiqzadeh. The Azerbaijan National History Museum This trading mission was directed by Richard Johnson, Alexander Kitchin and

Arthur Edwards and lasted from 1565 - 1567. We have a great deal of useful historical information from materials connected with that expedition. Two letters sent by Arthur Edwards from Azerbaijan to England are particularly valuable; they were sent from Shamakha in 1566. The first was dated 26 April and the second was written on 8 August. I’d like to consider these valuable documents separately, revealing, as they do, the English merchant’s personal views. So, about the first letter…

When Arthur Edwards wrote his first letter, more than 7 months had passed since his arrival in Azerbaijan. He had been able to acquaint himself closely with trading life in Shamakha, the economy of the surrounding regions and generally with the Azerbaijani way of life. We may, therefore give credence to much of the information he gives.

It is clear from the opening that Anglo-Azerbaijani trading relationships were already being strengthened by Shirvan’s governor, Adbullah Khan. As before, he had received the merchants in person, proving that the decree issued to Anthony Jenkinson was still in force, and he had even ordered the preparation of:

a good house for the English merchants at any place in Shamakha that they would consider appropriate

in other words, he provided a separate building for the English trading post.

Edwards openly declared the English trading company’s real purpose regarding Azerbaijan - they planned to monopolize the raw silk trade:

I have no doubt that very soon we will become a big company in the trade of raw silk, silk cloth, spices and dyeing materials, as well as other goods here.

Other interesting information in this part of the letter is that the English merchants, besides the raw silk, spices, silk cloth, jewels and other valuable goods, were interested in dyeing materials. Azerbaijan, well-known for its colourful, richly-patterned carpets and silk cloth was also home to craftsmen who produced very clear dyes in rich and delicate shades. There was great demand for these dyes in England as production there increased.

Edwards also revealed that Russo-Azerbaijani relationships were developing well at that time. These relations had already expanded to the extent that Russian had become the language of discourse between local and English merchants. Russian merchants or other Russian speakers usually mediated in negotiations between English and Azerbaijani merchants.

England, Iberia, Italy…

We have interesting information about reciprocal relations between the Safavids and Spain and Portugal in the 16th century. Edwards wrote that they needed someone who spoke Portuguese, as well as a Russian speaker:

A person who can speak Portuguese (if we could find such person) could also benefit our company a lot.

Alum was another product that the foreign merchants bought from Azerbaijan. Edwards wrote that he had

prepared 223 batman of alum as a sample for sending to England

from Shamakha’s bazaars. This valuable mineral was also in demand at home for the production of leather goods, one of England’s traditional exports.

The English traveller mentions three Safavid cities, which comprised the heart of the country, and their population was more civilized. Two of them were the Azerbaijani cities of Tabriz and Ardebil. This information is valuable for research into the economic role of Azerbaijani cities within the Safavid state.

Edwards wrote an interesting recommendation to the management of the Muscovy company to ensure success in selling English goods in Azerbaijan

It is not worth sending your red London cloth. Red cloth with eastern prints dyed in Venice sell very well here...

This note is telling, not only because it indicates that the Venetians still dominated the English in competition for Azerbaijani markets, that there were ancient trading relations between Italy and Azerbaijan and that the Venetians profited from dying cloth with eastern patterns; it also indicates that the local population had exquisite taste.

At the end of his letter, Edwards provided a list of the goods that he advised should be taken from Azerbaijan to England and those that should be brought from England to Azerbaijan.

On 26 April 1566, immediately after sending his letter to the Muscovy company, Edwards went to the Safavid Palace in Qazvin and from 2-9 May 1566 he met the Safavid ruler Shah Tahmasib, conducting negotiations with him. Following the trip to Qazvin, he sent his second letter from Shamakha to England, on 8 August 1566.

This letter is even more interesting and valuable. In April, when he wrote his first letter, Edwards had seen only Shamakha and the surrounding regions, but by his second letter he had been to Qazvin, seen the southern parts of Azerbaijan and had gathered information about the Safavid state. He was familiar with both the country’s domestic life and its international trading relations. That is why in his second letter the traveller developed his initial considerations, clarified them and, most importantly, provided concrete information.

Breakthrough in Qazvin

It is clear from the second letter that Edwards’ negotiations with the Safavid ruler were successful; the Muscovy company had finally found the right approach. The merchant described the meeting:

On the 29th of the same month (May 1566 – Y.M) I appeared before him and I think we had about two hours of conversation. Twice he summoned me and asked if I had any requests. He listened to my requests and graciously promised that he would give me the documents I wanted. Later, he called me back twice more and asked questions about our kingdom, our country, about the goods we had and which goods we wished to buy here; he also asked questions about our neighbouring countries and the goods they had.

As we learn from the letter, the Shah’s benevolent reception and their two-hour conversation were not without reason. The Ottoman Empire and Portuguese had closed the Safavids’ access to the Mediterranean and Black Seas and to the Indian Ocean, the importance of the Volga-Caspian route for the state’s relations with the outside world and particularly for trading relations with England had greatly increased. When Shah Tahmasib understood which goods were of interest to the English merchants and which they wished to export from the Safavid state, he also expressed his thoughts about goods he wanted to be brought from England. Edwards wrote:

Afterwards, the Shah told me which of our goods he would like to purchase. At the end of the meeting, he said that Your Honour might send him any type of cloth. He immediately ordered his secretary to write down his wishes: three or four bales of each type of well-made, patterned London cloth as a sample.

The merchant also gave his views on which cloths would be particularly successful in the Safavid state.

On 29 May1566, during his negotiations with Shah Tahmasib, Edwards obtained a decree of privileges for the English merchants.

The Shah told me that if you do not like the documents you have received they can be changed in the future.

You want 100? – We’ll send 200!

From the letter it seems that the shah was not in a hurry to give a wide range of privileges to the English merchants, he wanted to see in practice how advantageous these new trading relations would be for his country. This is why he told the messenger from the English kingdom:

if your merchants have reasonable requests we will show mercy to them in the future.

The information given by the English traveller is most valuable in building a picture of the Safavids’ foreign trading opportunities. He wrote:

the Shah asked me if you can send him 100,000 bales of cloth per year. I answered that you can supply his country with 200,000 bales of cloth. His Majesty was very happy with that...

In this letter, Edwards showed that Azerbaijan kept trading relations with western countries, particularly with Venice, via Haleb (Aleppo, Syria); he listed the goods taken to that famous trading centre and wrote that raw silk was a means of exchange in trading relationships with western countries.

The English merchant suggested to local merchants in Shamakha that, instead of taking raw silk to Haleb, they could exchange it locally for English cloth. They agreed and even promised to supply the English merchants with spices. Here Edwards wrote: I have no doubt that we will gradually gain success in the spice and dye trades and this will be profitable.

When writing about the country’s foreign trading relations, Edwards, who stated that each year at least five or six thousands bales of wool cloth was imported from Haleb, did not forget ‘the main issue’, which was the silk trade. He detailed the foreign trade capacity of the Safavid state and did not believe that the English could purchase all the silk it exported.

Cash discount

The traveller returns to the question of purchasing ‘first hand’ silk. He wished to have extra money to buy silk from villagers at a low price. In this he envied the Turkish merchants, who were the main purchasers of Azerbaijani silk and England’s main rivals in trade:

Because they have cash, the Turks buy silk from the villagers at a low price as soon as they take it to market at the appropriate time of year.

The English merchant drafted a plan to supplant the Turkish merchants, not only in the silk trade, but in other areas, too. As mentioned above, Turkish merchants mainly offered silver for silk. There was great demand for silver in Azerbaijan because, besides the production of handicrafts, it was also used to produce money. This final element drew the Englishman’s attention. He wrote to London:

I would like you to send some silver in the form of bullion, to mint coins. The local governor would like it very much and it would be very profitable for us.

Thus, Azerbaijani governors and the Safavid ruler was looking for partners to bolster international trading relations and resolve problems of foreign policy, and they were applying to various countries, including European states.

Edwards wrote a third letter to England about his visit to the Safavid Palace. He wrote it in Astrakhan, while on his way back after completing his trip. In this document, written on 16 June 1567, he quoted from Shah Tahmasib’s decree afforded to the English merchants. He listed the privileges that represented initiatives by the Safavids, prevented from trading in the Mediterranean Sea, Black Sea and Indian Ocean, to export raw silk, which was the country’s main source of wealth, to Europe via trading relations with the English merchants.

Azerbaijani, language of diplomacy

According to Edwards’ notes, the Safavid governor had released merchants of the Muscovy company from customs duties and fees. The English also had permission to pass through the country to neighbouring states.

Shah Tahmasib had bestowed other privileges on the London merchants:

In all the cities where the English go and stay, the viceroys, local governors and court judges should take care of them, provide assistance, protect them from bad people, and punish any person who would harm them.

Edwards wrote:

After our goods have been transported to the seashore, with the help of God, the Shah’s servants should assist us in the transportation of these goods overland.

Further, those who took goods on credit and did not pay, bought goods without the merchant’s full consent, received gifts and even those who wanted to return goods they had purchased, would be punished.

After Edwards had listed these trading privileges, he wrote that the Safavid leader

…ordered his secretary to write the abovementioned articles (he meant the articles in the decree of privilege – Y. M.) into each of four letters. Then he gave these letters to me. At my request, two of them have been written in Turkish (ie. Azerbaijani – Y. M.) to send to you. On the back of one of the letters the secretary has written a list of goods that His Majesty would like to buy from you.

We think that this passage is very important as historical information, particularly for the history of our language. The fact that on 29 May 1566 the Safavid shah sent very important diplomatic documents from Qazvin to England written in Azerbaijani proves that the traditions set by Shah Ismail Khatai were still in place in the Safavid Palace and that Azerbaijani was the official language and the language of diplomatic correspondence.

About the Author: Yagub Mahmudov is Director of the History Institute of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences (ANAS)‚ professor and corresponding member of ANAS. He is a well-known specialist on medieval history. He is author of monographs and articles on issues relating to the history of Azerbaijan.