Pages 92-94

Pages 92-94 by Rustam Alasgarov

You can’t miss Bibi-Heybat mosque as you head south past the lower tip of Baku bay; its two minarets dominate the headland. The location was no casual choice for this prominent shrine; it has long been revered as a sanctuary. When Islam spread to Azerbaijan, popular holy places were assimilated and given Arabic and Muslim names.

Despite its relatively small size, the original mosque was one of the main sights of old Baku; it blended perfectly with its surroundings and also somehow took on different identities from different angles. You can see this from old photographs. A look at the chronology of the complex’s construction and modification gives us an idea of how Bibi-Heybat developed.

The first mosque was built by Hokuma khanim. Fleeing with her servant Heybat from persecution by the Arab Caliphate, she arrived at this ancient sacred spot on the Caspian’s rocky coast, in Shikhov village, and later erected the small mosque which was to become her final resting place.

Bibi (aunt) was the respectful term by which Heybat addressed her mistress and so the name was given to the mosque that Hokuma khanim had raised. When Heybat died and was buried, as he had requested, at the feet of his ‘aunt’ in the same mosque, his name was also added. Since then the mountain, the village and the mosque have all been called Bibi-Heybat.

The work of Mahmud Ibn Saad

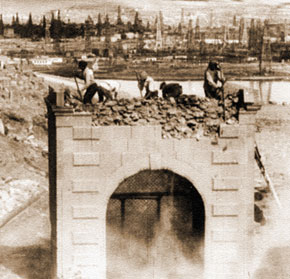

Historians have established that the present complex is the result of six stages of building, each stage marked by the addition of a new construction. Besides the main group of buildings, the northern and southern gates, the mausoleums, underground wells, pools and various administrative premises and utility rooms have been included into the Bibi-Heybat religious and memorial complex.

The main buildings were not constructed to a unified plan: they were erected by various architects between the 13th and early 20th centuries. First to be built were the old mosque and minaret. There was a small stone inscribed with the architect’s name on the mosque’s southern facade: The work of Mahmud Ibn Saad.

The minaret’s construction had all the traits of the Shirvan school of architecture and is important to the study of similar buildings on Absheron. It was 22 metres high, with an adjoining burial vault-mausoleum and the mosque on the northern side. The inscription on it was translated by the German orientalist, Dorn; it said that it was erected in 1619 by Sheikh Sherif Ben Sheikh Abid, who had died the day following its completion and was entombed there, too.

Najaf restores, Alibek captures

The tomb was constructed under a central dome. This fluted dome stood on a dodecahedral drum which, in turn, rested upon four arches and was covered by mirrored glass. During the last restoration in 1911 these mirrored pieces were removed. Lancet arches decorated the dome’s eaves.

As well as the tomb in the centre of the hall, there were two others under the western vault. It seems that the facades of the burial vault were given an additional layer of stone in 1911. The incorporation of the burial vault into the mosque necessitated the closure of the entrance and two windows on the northern side, not needed in a burial vault.

The mosque’s architecture and layout identifies it as being one of the neighbourhood mosques common in medieval Baku. It was square in design and was noted for the lancet arch in the middle of the wall, above ground level. The rim of the mihrab (niche indicating the direction to Mecca) was decorated with stalactites and carved ornaments. There was a small window above the mihrab. There was a niche between the doorways leading to an arcade. The mosque was connected to the later construction through a lancet arch in the north wall. The mosque floor was paved with green-glazed brick flags.

The completion of the main group of buildings with the construction of the new mosque changed completely the architectural and spatial composition of the whole complex. The name of the architect, Haji Najaf of Baku, the date of construction Hegira 1330 (AD 1911) and the name of the benefactor who provided the means, Alesker Aga Dadash-zadeh, were inscribed above a supporting arch. The text was in three couplets of Persian verse and executed in magnificent calligraphy.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the mosque/burial vault was used for general worship. People of various conditions, especially those suffering from illness, dervishes, wanderers and the disabled thronged there.

The eminent artist Alibek Huseyn-zadeh painted a picture, Bibi-Heybat Mosque, which was coveted by the English consul. However, Haji Zeynalabdin Tagiyev tripled the consul’s bid in order not to keep the picture in the country. It is held now in the Rustam Mustafayev State Museum of Art. It was as if the famous benefactor had a presentiment that the mosque’s life would be cut short – with the arrival of the Bolsheviks.

Religion under attack

Unfortunately, this was the case. The Soviet authorities declared all religions to be the opium of the people and so began the persecution and extermination of clergy and the destruction of temples of all traditional religions.

The magazine Sharq Gapisi (door to the East), published from 1923 in Baku, was the first mass, antireligious publication. The struggle against religion in society, the right of Azerbaijani women to education, and the emancipation and rights of Eastern women were reflected in its pages. The many cartoons published, alongside periodic jabs at illiteracy and infringements of women’s rights, aimed particular swipes at religious fanaticism and superstition.

Culture, as well as people, suffered under the repression of the 1930s. Along with the intelligentsia, a cultural heritage, including its traditions of tolerance and leniency developed over centuries, was destroyed. The first years of Soviet power, years of militant atheism, had a most pernicious effect on religious buildings.

The satirical magazine Allahsiz (Atheist) was published from 1931 to 1933 in Baku, following the closure of the Molla Nasreddin magazine. It did not, however, achieve the popularity of its predecessor and never rose to the same level.

The magazine was the organ of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and served Soviet ideology. It mainly contained political posters, satirical drawings and cartoons. It also published many pictures by artists and cartoonists on religious and political themes.

At that time many mosques and churches were destroyed or turned into warehouses. During this tragic period, remarkable temples like the Orthodox cathedral of Alexander Nevsky, the Catholic Church of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary and the Bibi-Heybat mosque disappeared from Baku.

Poisoned chalice

At first Ruhullah Akhundov was entrusted with the demolition of Bibi-Heybat’s unique mosque. This was a deliberate move as Ruhullah Akhundov was from a spiritual environment. However, he proved to be too busy with affairs of state to carry out the mission. So the task was given to a party member in a lesser position who was willing to implement any order that came ‘from above’.

The director of the Azerbaijan Museum of History of the day, Movsum Sanan-zadeh managed by some miracle to rescue the remains and tombstone of Fatali khan Gubinsky just before the demolition.

Memories of that awful time are simply terrifying: the person supervising the demolition of the mosque, by order of party leader Mir Jafar Baghirov, was subsequently himself subjected to repression. One count in his indictment was the demolition of a historical monument.

Thus the Bibi-Heybat religious and memorial complex was blown up in the last days of September 1936. Many of its buildings fell after the first explosion. The minaret, the pride of Bibi-Heybat, turned out to be the most durable and tumbled only after the third blast.

Independence and revival

When Azerbaijan regained its independence, most of the Islamic religious constructions which had survived were transferred to believers and the building of new mosques began. Many mosques have been restored and constructed in recent years. Just in Baku, along with those restored, the Shahidler (martyr’s) mosque, the Abu-Bakr mosque, the Bibi-Heybat mosque and many others newly built – more than 1,200 –began to function. There are now about 700 mosques in daily use.