Pages 48-50

By Farhad Mammadov

Despite repeated requests by the OSCE’s Minsk Group, Armenia is again organizing further resettlement of Armenians living abroad to the occupied Azerbaijani territories in Karabakh. This is evident from an article by an Armenian journalist working in Los Angeles, USA and posted on the Eurasianet.org website (http://www.eurasianet.org/node/64435). It states that to prevent the steady outflow of human capital a new campaign has been started to resettle Armenians residing in foreign countries to Armenia and occupied Nagorno Karabakh. But the government of Armenia is remaining officially distant from this campaign, saying it is a private initiative. The essence of the campaign is to convince rich Armenians living mainly in Western countries and able to support themselves, to move to their ‘homeland’ and Karabakh. This feature of the campaign seems to indicate that Armenia’s economic capacity does not allow for poor Armenians to resettle in Karabakh and enjoy normal living conditions.

In fact the Armenian government began organising the resettlement of Armenians from abroad to the occupied territories in the mid 1990s. The OSCE’s international mission to investigate the situation in the occupied territories has, in recent years, twice confirmed that unlawful resettlement is being carried out. In 2006, the mission gave a figure of about 17,000 people. In 2010, it concluded that the unlawful resettlement was continuing. It revealed that Armenians, mainly from the Middle East, had been resettled in the occupied regions of Lachin, Kalbajar and Zangilan, financed by the Armenian government. The new arrivals were provided with one-off financial aid, free domestic animals and extensive sowing areas. Later, however, the country’s budget did not allow the programme to continue and many of the settlers left after exhausting the aid given them. Thousands of Armenians have moved from Nagorno Karabakh to Russia’s Northern Caucasus regions in the last two years. The government’s failure to strengthen its position in the occupied Azerbaijani territories by unlawful resettlement has provoked criticism from within Armenia. Although finance is one aspect of its failure, the policy has also been hampered by Azerbaijan raising the issue sharply in bilateral negotiations and before international organizations.

Armenia-3500 dreams

The article refers to the new initiative as Armenia-3500. The intention is for 3,500 Armenian families to move to Armenia and Karabakh. The article states that the drivers of the initiative – leaders of the Armenian diaspora, public organizations and movements have highlighted a group of young Armenians settled in Armenia and Karabakh as examples. It points out that Armenia has one of the highest migration flows from the former Soviet republics. Its people emigrate to Russia and other foreign countries on a mass scale. Such a rapid decline in human capital is a threat to Armenia’s national security, and this outflow is one of the main focuses for opposition and public criticism of the government. The opposition says that this trend will eventually end in Armenia’s loss of Karabakh in the future.

As part of this campaign, the Armenian diaspora in the west has launched a TV advertising campaign. The campaign shows ‘how well’ Armenians who moved to Armenia and Karabakh live (although the OSCE saw:

stark evidence of the disastrous consequences of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

forcing people to

live in precarious conditions

just one year ago). The idea is that the future of Armenia depends on its defensive capacity and reputation, i.e. it will not be possible to ensure this defence without organising a movement of Armenians from abroad to the ‘motherland’.

Many incentives are promised by the Armenia-3500 campaign to those who wish to settle in Nagorno Karabakh. They believe that convincing rich Armenians to settle in Karabakh will generate new jobs and investment in the territories. It is interesting that those behind the campaign to encourage illegal occupation do not disclose their identity. The article says that the project was launched just a few months ago, but Armenians from the US, Great Britain and Germany have already joined it.

Professor pours cold water

Some experts, however, doubt the viability of the campaign. Professor Stephan Astourian, executive director of the Armenian Studies programme at the University of California, says that repatriation since Armenia gained independence has been minimal at best.

The fact of the matter is that a miniscule number of Armenians have repatriated, with the exception of one country - Iran.

He believes that 5,000 to 10,000 Armenians have repatriated since 1991 but official data was not immediately available. The United Nations Development Programme estimates that as many as 1.3 million Armenians have left the country within this period. Astourian claims that the reasons for low diaspora interest in returning to live in Armenia are the same ones that have prompted others to leave:

There is a lack of rule of law and freedom and, economic difficulties plus rampant corruption.

He says that repatriation would be highly desirable if there was a state based on the rule of law, with the police under control, genuine parliamentary life and judiciary.

The article tells the story of Armen Rakedjian, who relocated from Paris to the Nagorno-Karabakh town of Shusha in 2004. He has firsthand experience of the red tape and corruption plaguing the region. After moving to Shusha, he became caught up in a dispute over improperly registered property that ultimately cost him his entire $50,000 investment. He blames his loss on the alleged need to pay bribes and ‘high salaries’ to correct the problem. Nonetheless, Armen decided to stay in Shusha, where he runs a B&B with his wife. In France, he said:

I don´t have any insurance that my daughter will stay Armenian, or the children of my daughter.

Armenian government support for the Armenia-3500 programme is unclear, with no comment from Armenia’s Ministry of Diaspora. Without such support, Victor Sargissian, who moved from California to Yerevan, had to return last summer as he and his wife found it impossible to establish a reasonable standard of living.

Milk sop

It is unlikely that the Sargissians are the only ones disheartened by the struggle, and it is even harder for those in the occupied territories. The armed invasion resulted in the destruction of infrastructure and high unemployment. The country’s budget is hardly enough to continue subsidising those who have transferred to these areas. Moreover, negotiations to settle the conflict have so far proved fruitless and there is still a risk of military hostilities resuming. The idea that Armenians who have built a comfortable life in the U.S. and Europe may be tempted to move to ruined Azerbaijani villages by the promise of a

Free house and cow in Karabakh

(Reasons to move, No1 http://armenia3500.wordpress.com/reasons-to-move)

seems somewhat fanciful. Of course, there may be the exceptionally committed patriots who, despite the difficulties, will make the sacrifice to live in the ‘historical homeland’.

Temporary permanence

This vision of Karabakh as the ‘Armenian homeland’ is disputed by authoritative historians who point to the mass transfer of Armenians from Persia to the region following tsarist Russian conquest in the early 19th century. 40,000 Armenians from Iran transferred to the various regions of Azerbaijan, including Karabakh following the Turkmenchay Treaty signed by Russia and Persia in 1828. More than 90,000 Armenians were relocated after the Russian and Ottoman Empires signed a peace treaty in 1829. They were mainly resettled in the Nakhchivan, Irevan and Karabakh khanates. A monument was erected in 1978 commemorating 150 years of settlement – it has since been destroyed, presumably as being inconvenient to the concept of Karabakh as ‘historical homeland’. The eminent Russian diplomat and writer A. S. Griboyedov, who contributed to the formulation of the Turkmenchay treaty, wrote about the Armenian migration to the Azerbaijani territories:

The Armenian population settled in the areas of Muslim landowners, they slowly started to remove the Muslim population from their own lands. Also we should try to reconcile the Muslim population to the difficult situation that they are enduring and convince them that the difficulties will not last long and the areas allocated to Armenians for temporary settlement is not permanent.

But the Armenian settlement proved not to be temporary, on the contrary they increased and by the end of the 20th century they had occupied Nagorno-Karabakh and seven adjacent Azerbaijani districts, forcing hundreds of thousands of refugees from their homes. Now, the policy of artificially changing the demography of the region continues with this new initiative to invite the diaspora to the occupied territories.

And so it goes on…

Armenia-3500 is not the only resettlement plan currently afoot. In May this year, preparations began for the movement of Hamshen Armenians (who are Muslim) from the Central Asian republics to occupied Azerbaijani land. The plan here is to settle 200 Hamshen Armenian families from Kyrgyzstan in Agdere region and provide them with plots of land and domestic animals. Hamshen Armenians are mainly engaged in cattle-breeding in their current homeland. The Russian Union of Hamshen Armenians is supporting this project and a spokesman, Georgi Mkhitaryan, said that further resettlement of Hamshen Armenians from Russia and Kazakhstan is planned. Of course, the Azerbaijani government has raised this matter with international organisations.

…and on…

This propensity to arrive as guests and then to occupy others’ territories is arousing concern in neighbouring Georgia too. There, former president Eduard Shevardnadze has expressed concern in an interview with the Tbilisi newspaper Asaval-Dasavali about the Georgian parliament´s adoption of amendments to the status of religious communities, including that of the Armenian Church; these changes, he said, may lead to claims, not only for Armenian churches in Georgia, but also for Georgian land. (http://www.epress.am/en/2011/07/11/armenians-might-ask-for-georgian-lands-too-warns-shevardnadze.html)

The former president is also anxious about negotiations to build a new road between Armenia and Georgia’s Adjara. Shevardnadze warned of a possible problem, saying that the demographic situation could change in Adjara, with Armenians predominating: Look at Abkhazia, there are more Armenians than Abkhazians, he said.

http://www.epress.am/en/2011/12/05/road-linking-armenia-to-batumi-will-raise-problems-for-georgia-shevardnadze.html

…and on…

A report published in Russia’s Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper tells the interesting story of a similar expansion of ‘temporary’ stay. (Http://kp.ru/daily/25802.5/2783472/) 74-year-old pensioner Nikolay Podolnıy, from Yutsa in Stavropol province, in the late 90s helped an Armenian family that had moved from Nagorno-Karabakh because of unemployment and the difficult social conditions. A few years later the family he had helped took Nikolay’s land and now nobody wants to listen to his complaint.

Thus, Armenia-3500 follows a pattern of occupation and consolidation of ‘homelands’. However, it seems unlikely that the carrot, or rather cow, it dangles this time will be sufficient to entice the diaspora to an illegally and ruinously occupied land to live with the ever-present likelihood of having to move out again. Better, surely, for the Armenians established in Karabakh and the seven other occupied territories to access the vast resources and development available within internationally recognised borders?

By Farhad Mammadov

Despite repeated requests by the OSCE’s Minsk Group, Armenia is again organizing further resettlement of Armenians living abroad to the occupied Azerbaijani territories in Karabakh. This is evident from an article by an Armenian journalist working in Los Angeles, USA and posted on the Eurasianet.org website (http://www.eurasianet.org/node/64435). It states that to prevent the steady outflow of human capital a new campaign has been started to resettle Armenians residing in foreign countries to Armenia and occupied Nagorno Karabakh. But the government of Armenia is remaining officially distant from this campaign, saying it is a private initiative. The essence of the campaign is to convince rich Armenians living mainly in Western countries and able to support themselves, to move to their ‘homeland’ and Karabakh. This feature of the campaign seems to indicate that Armenia’s economic capacity does not allow for poor Armenians to resettle in Karabakh and enjoy normal living conditions.

In fact the Armenian government began organising the resettlement of Armenians from abroad to the occupied territories in the mid 1990s. The OSCE’s international mission to investigate the situation in the occupied territories has, in recent years, twice confirmed that unlawful resettlement is being carried out. In 2006, the mission gave a figure of about 17,000 people. In 2010, it concluded that the unlawful resettlement was continuing. It revealed that Armenians, mainly from the Middle East, had been resettled in the occupied regions of Lachin, Kalbajar and Zangilan, financed by the Armenian government. The new arrivals were provided with one-off financial aid, free domestic animals and extensive sowing areas. Later, however, the country’s budget did not allow the programme to continue and many of the settlers left after exhausting the aid given them. Thousands of Armenians have moved from Nagorno Karabakh to Russia’s Northern Caucasus regions in the last two years. The government’s failure to strengthen its position in the occupied Azerbaijani territories by unlawful resettlement has provoked criticism from within Armenia. Although finance is one aspect of its failure, the policy has also been hampered by Azerbaijan raising the issue sharply in bilateral negotiations and before international organizations.

Armenia-3500 dreams

The article refers to the new initiative as Armenia-3500. The intention is for 3,500 Armenian families to move to Armenia and Karabakh. The article states that the drivers of the initiative – leaders of the Armenian diaspora, public organizations and movements have highlighted a group of young Armenians settled in Armenia and Karabakh as examples. It points out that Armenia has one of the highest migration flows from the former Soviet republics. Its people emigrate to Russia and other foreign countries on a mass scale. Such a rapid decline in human capital is a threat to Armenia’s national security, and this outflow is one of the main focuses for opposition and public criticism of the government. The opposition says that this trend will eventually end in Armenia’s loss of Karabakh in the future.

As part of this campaign, the Armenian diaspora in the west has launched a TV advertising campaign. The campaign shows ‘how well’ Armenians who moved to Armenia and Karabakh live (although the OSCE saw:

stark evidence of the disastrous consequences of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

forcing people to

live in precarious conditions

just one year ago). The idea is that the future of Armenia depends on its defensive capacity and reputation, i.e. it will not be possible to ensure this defence without organising a movement of Armenians from abroad to the ‘motherland’.

Many incentives are promised by the Armenia-3500 campaign to those who wish to settle in Nagorno Karabakh. They believe that convincing rich Armenians to settle in Karabakh will generate new jobs and investment in the territories. It is interesting that those behind the campaign to encourage illegal occupation do not disclose their identity. The article says that the project was launched just a few months ago, but Armenians from the US, Great Britain and Germany have already joined it.

Professor pours cold water

Some experts, however, doubt the viability of the campaign. Professor Stephan Astourian, executive director of the Armenian Studies programme at the University of California, says that repatriation since Armenia gained independence has been minimal at best.

The fact of the matter is that a miniscule number of Armenians have repatriated, with the exception of one country - Iran.

He believes that 5,000 to 10,000 Armenians have repatriated since 1991 but official data was not immediately available. The United Nations Development Programme estimates that as many as 1.3 million Armenians have left the country within this period. Astourian claims that the reasons for low diaspora interest in returning to live in Armenia are the same ones that have prompted others to leave:

There is a lack of rule of law and freedom and, economic difficulties plus rampant corruption.

He says that repatriation would be highly desirable if there was a state based on the rule of law, with the police under control, genuine parliamentary life and judiciary.

The article tells the story of Armen Rakedjian, who relocated from Paris to the Nagorno-Karabakh town of Shusha in 2004. He has firsthand experience of the red tape and corruption plaguing the region. After moving to Shusha, he became caught up in a dispute over improperly registered property that ultimately cost him his entire $50,000 investment. He blames his loss on the alleged need to pay bribes and ‘high salaries’ to correct the problem. Nonetheless, Armen decided to stay in Shusha, where he runs a B&B with his wife. In France, he said:

I don´t have any insurance that my daughter will stay Armenian, or the children of my daughter.

Armenian government support for the Armenia-3500 programme is unclear, with no comment from Armenia’s Ministry of Diaspora. Without such support, Victor Sargissian, who moved from California to Yerevan, had to return last summer as he and his wife found it impossible to establish a reasonable standard of living.

Milk sop

It is unlikely that the Sargissians are the only ones disheartened by the struggle, and it is even harder for those in the occupied territories. The armed invasion resulted in the destruction of infrastructure and high unemployment. The country’s budget is hardly enough to continue subsidising those who have transferred to these areas. Moreover, negotiations to settle the conflict have so far proved fruitless and there is still a risk of military hostilities resuming. The idea that Armenians who have built a comfortable life in the U.S. and Europe may be tempted to move to ruined Azerbaijani villages by the promise of a

Free house and cow in Karabakh

(Reasons to move, No1 http://armenia3500.wordpress.com/reasons-to-move)

seems somewhat fanciful. Of course, there may be the exceptionally committed patriots who, despite the difficulties, will make the sacrifice to live in the ‘historical homeland’.

Temporary permanence

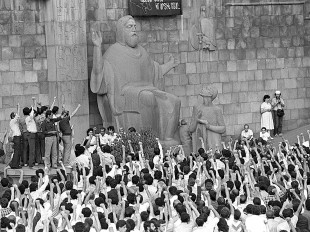

This vision of Karabakh as the ‘Armenian homeland’ is disputed by authoritative historians who point to the mass transfer of Armenians from Persia to the region following tsarist Russian conquest in the early 19th century. 40,000 Armenians from Iran transferred to the various regions of Azerbaijan, including Karabakh following the Turkmenchay Treaty signed by Russia and Persia in 1828. More than 90,000 Armenians were relocated after the Russian and Ottoman Empires signed a peace treaty in 1829. They were mainly resettled in the Nakhchivan, Irevan and Karabakh khanates. A monument was erected in 1978 commemorating 150 years of settlement – it has since been destroyed, presumably as being inconvenient to the concept of Karabakh as ‘historical homeland’. The eminent Russian diplomat and writer A. S. Griboyedov, who contributed to the formulation of the Turkmenchay treaty, wrote about the Armenian migration to the Azerbaijani territories:

The Armenian population settled in the areas of Muslim landowners, they slowly started to remove the Muslim population from their own lands. Also we should try to reconcile the Muslim population to the difficult situation that they are enduring and convince them that the difficulties will not last long and the areas allocated to Armenians for temporary settlement is not permanent.

But the Armenian settlement proved not to be temporary, on the contrary they increased and by the end of the 20th century they had occupied Nagorno-Karabakh and seven adjacent Azerbaijani districts, forcing hundreds of thousands of refugees from their homes. Now, the policy of artificially changing the demography of the region continues with this new initiative to invite the diaspora to the occupied territories.

And so it goes on…

Armenia-3500 is not the only resettlement plan currently afoot. In May this year, preparations began for the movement of Hamshen Armenians (who are Muslim) from the Central Asian republics to occupied Azerbaijani land. The plan here is to settle 200 Hamshen Armenian families from Kyrgyzstan in Agdere region and provide them with plots of land and domestic animals. Hamshen Armenians are mainly engaged in cattle-breeding in their current homeland. The Russian Union of Hamshen Armenians is supporting this project and a spokesman, Georgi Mkhitaryan, said that further resettlement of Hamshen Armenians from Russia and Kazakhstan is planned. Of course, the Azerbaijani government has raised this matter with international organisations.

…and on…

This propensity to arrive as guests and then to occupy others’ territories is arousing concern in neighbouring Georgia too. There, former president Eduard Shevardnadze has expressed concern in an interview with the Tbilisi newspaper Asaval-Dasavali about the Georgian parliament´s adoption of amendments to the status of religious communities, including that of the Armenian Church; these changes, he said, may lead to claims, not only for Armenian churches in Georgia, but also for Georgian land. (http://www.epress.am/en/2011/07/11/armenians-might-ask-for-georgian-lands-too-warns-shevardnadze.html)

The former president is also anxious about negotiations to build a new road between Armenia and Georgia’s Adjara. Shevardnadze warned of a possible problem, saying that the demographic situation could change in Adjara, with Armenians predominating: Look at Abkhazia, there are more Armenians than Abkhazians, he said.

http://www.epress.am/en/2011/12/05/road-linking-armenia-to-batumi-will-raise-problems-for-georgia-shevardnadze.html

…and on…

A report published in Russia’s Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper tells the interesting story of a similar expansion of ‘temporary’ stay. (Http://kp.ru/daily/25802.5/2783472/) 74-year-old pensioner Nikolay Podolnıy, from Yutsa in Stavropol province, in the late 90s helped an Armenian family that had moved from Nagorno-Karabakh because of unemployment and the difficult social conditions. A few years later the family he had helped took Nikolay’s land and now nobody wants to listen to his complaint.

Thus, Armenia-3500 follows a pattern of occupation and consolidation of ‘homelands’. However, it seems unlikely that the carrot, or rather cow, it dangles this time will be sufficient to entice the diaspora to an illegally and ruinously occupied land to live with the ever-present likelihood of having to move out again. Better, surely, for the Armenians established in Karabakh and the seven other occupied territories to access the vast resources and development available within internationally recognised borders?