Pages 46-51

by Karim K. Shukurov

The Azerbaijani Republic declared state independence on 18 October 1991. Following this a speedy process of integration into the world community began. Azerbaijan joined the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) on 30 January 1992, the United Nations Organization (UN) on 2 March 1992 and other international and regional organizations.

The building of an open society in Azerbaijan created greater opportunities for citizens of foreign countries to come to Azerbaijan, both to work and as tourists. In such circumstances, there has been a natural increase in interest in all spheres of Azerbaijani life, including its historical past.

However there are, currently, no materials in English either in Azerbaijan itself or in other countries and so there are certain problems in meeting this interest. ‘Visions of Azerbaijan’ has taken note and has published articles about various periods of Azerbaijan’s historical past and related issues.

As well as continuing this positive practice, the magazine is also aware of current demand and has decided to implement a new project reflecting the country’s history in a systematic and chronological way. We now present the first section of this project, which has been written by Karim Shukurov, Doctor of Historical Science.

As

Primitive Society Azerbaijan: archaeological periods and monuments (2/2,5 min years ago - III millennium B.C.)

Primitive Society Azerbaijan: archaeological periods and monuments (2/2,5 min years ago - III millennium B.C.) Azerbaij an is rich in abundant natural resources and mineral springs. It has eight of the Earth’s 11 climatic zones; the three missing are tropical forests, savannahs and permanent cold. It also has unique flora and fauna.

The favourable natural and geographical environment in Azerbaijan made it one of the first places in the world to be inhabited by humans. According to the latest scientific research, homo habilis (‘handy man’) settled here about 2-2.5m years ago.

Thus, Azerbaijan’s history “started”.

The periodifi cation of Azerbaijan’s history

The periodification of history is a theoretical and methodological issue and proceeds from the essence of historical concepts. Within his theory of historical materialism, Karl Marx (1818-1883) divided human history into fi ve socio-economic formations (primitive community, slavery, feudalism, capitalism and communism). One might say that historical materialism, which became the official state theory of the Soviet era (1917-1991), collapsed with its fall. The theory of local civilizations has been at the centre of attention ever since it appeared. N. Y. Danilevsky (1822-1885), O. Spengler (1880-1936) and A. Toynbee (1889-1975) identified a number of local civilizations.

K. Jaspers (1883-1969), who proceeded from the theory of the unity of world history, split human history into three phases which replaced each other consecutively (pre-historic, historic and global historic).

Various periodifi cations have been used in studies of Azerbaijan’s history (one by A. Bakikhanov (1796-1846); independence, the personification of history and periodifi cation on the basis of foreign captivity, socio-economic formations etc). However, these ideas did not result in a full picture of the nation’s history. Thus the need emerged for a new version. An objective periodification of Azerbaijan’s historical material should be sought within its own historical development.

Here, the principal factor is Azerbaijani statehood. Once Azerbaijan had gone through its pre-state period, one struggle for statehood and state independence succeeded another, with a succession and obstinacy seen in no other country; the periods that emerged within these struggles were complete and, at the same time, distinct eras or civilizations. This approach to Azerbaijan’s history: 1) creates an objective picture of its historical development; 2) alongside a study of the objective history of each era (or civilization), identifies relationships between eras and their overall dynamic of development; 3) identifies the nation’s place and role in world history and makes it possible to apply to Azerbaijani history the general periodifications accepted for world history; 4) clarifies the experience and lessons that follow historical development.

K. Jaspers (1883-1969), who proceeded from the theory of the unity of world history, split human history into three phases which replaced each other consecutively (pre-historic, historic and global historic).

Various periodifi cations have been used in studies of Azerbaijan’s history (one by A. Bakikhanov (1796-1846); independence, the personification of history and periodifi cation on the basis of foreign captivity, socio-economic formations etc). However, these ideas did not result in a full picture of the nation’s history. Thus the need emerged for a new version. An objective periodification of Azerbaijan’s historical material should be sought within its own historical development.

Here, the principal factor is Azerbaijani statehood. Once Azerbaijan had gone through its pre-state period, one struggle for statehood and state independence succeeded another, with a succession and obstinacy seen in no other country; the periods that emerged within these struggles were complete and, at the same time, distinct eras or civilizations. This approach to Azerbaijan’s history: 1) creates an objective picture of its historical development; 2) alongside a study of the objective history of each era (or civilization), identifies relationships between eras and their overall dynamic of development; 3) identifies the nation’s place and role in world history and makes it possible to apply to Azerbaijani history the general periodifications accepted for world history; 4) clarifies the experience and lessons that follow historical development.

1. The Pre-State Period, or Primitive Society

2.5-2m Years Ago – Third Millennium BC

Pre-state period, or primitive society: time and development. Ancient community (parent community). Guruchay culture. First clan community. Gobustan site. Neolithic civilization. Collapse of primitive community.

The pre-state period or primitive society: time and development

It is a tricky business giving the same name to a period of world history and applying it to all countries and nations. However, the period before the establishment of a state is an exception. In essence and the main stages, this is the same throughout the world. This period may be described as primitive society.

The first aspects of primitive society to capture the attention are the unimaginably long period of time covered and the slow rate of development. From a historical point of view, the concept of time applied here is in stark contrast with that of later periods, especially in conditions of modern scientific technical progress: little changed over a long time in primitive society, while so much is happening within a short time in the modern period. For this reason, the premise is that primitive society should be measured not by the number of events in time but by their quality. This impacts upon the periodification of primitive society. For the time being, there is no single opinion on this issue. In this situation, a method that explains the main content of the periodification of primitive society intelligibly may be more useful. A synthesis of general historical and archaeological periodification is more appropriate here.

The first aspects of primitive society to capture the attention are the unimaginably long period of time covered and the slow rate of development. From a historical point of view, the concept of time applied here is in stark contrast with that of later periods, especially in conditions of modern scientific technical progress: little changed over a long time in primitive society, while so much is happening within a short time in the modern period. For this reason, the premise is that primitive society should be measured not by the number of events in time but by their quality. This impacts upon the periodification of primitive society. For the time being, there is no single opinion on this issue. In this situation, a method that explains the main content of the periodification of primitive society intelligibly may be more useful. A synthesis of general historical and archaeological periodification is more appropriate here.

Ancient community (parent community)

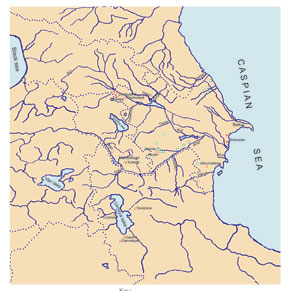

A period of primitive human herding is thought to be the fi rst form of human society – the parent community. Archaeologically, the parent community begins in the lower stage (2/2.5m – 100/120,000 years ago) of the Palaeolithic period (Latin: palaios – ancient, lithos – stone). Samples of material culture found by archaeological excavations conducted in the Karabakh region’s Azikh and Taglar, and Gazakh’s Dashsalahli and other Palaeolithic camps allow one a glimpse into the lives of the people that lived in that period.

The first human communities emerged on the basis of an instinct for communal living, and included 20 to 30 people.

Findings discovered at levels 7-10 of the multi-level Azikh cave and which entered archaeological literature as Guruchay (the valley where the cave is located) culture, are of special importance in terms of studying the earliest period of human society.

These findings show that the people were hunter gatherers. People’s lives often depended on hunting. Working tools improved from the lower levels upwards. A hearth found at level 6 and dated to 700,000 years ago confirmed that people had learned to make fire. Controlling fire gave a new stimulus to human life. It also enriched people’s spiritual lives and its unprecedented role in human life caused it to be sanctified. This continues in the present- day. Thus, holy places are called “hearths” in Azerbaijan.

A jawbone found at level 5 of the Azikh Palaeolithic camp in 1968, which belonged to homo habilis was a major scientific discovery.

Research established that the bone belonged to a woman aged 18-22 and that it dated to 350,000-400,000 years ago. Thus, people’s material lives and anthropological indicators were documented.

These early human remains have global significance and are called Azikhantrop. Azikhantrops were also engaged in construction and tried to create artificial living places – homes. A bear’s skull found in the Azikh cave has eight slanting lines inscribed on it and gives us some further insight into the mysterious spiritual life of the Azikhantrops. These lines could be a reflection of any thought, number, ritual, picture etc. The fact that such attention was paid to the skull of a bear, and not to other animals, is indicative of early totemism. The parent community ended with the Middle Palaeolithic (100/120 – 40,000 years ago), or Mousterian period, as it is referred to in archaeological literature (after the Le Moustier cave in France). The location of sites belonging to the Middle Palaeolithic (Buzeyir [Lerik District], Gazma [Sharur District], camps on the coast of Lake Orumiyeh etc), indicates the spread of people across the territory of Azerbaij an in that period. The techniques used in making tools were developed, as was their range. Practice in hunting, and improvements in weaponry, made this the main occupation. Hunting became men’s sphere of activity, while the women gathered. Alongside working life, there were also developments in people’s socio-cultural lives. Responsibilities emerged in mutual help and communal living.

The first human communities emerged on the basis of an instinct for communal living, and included 20 to 30 people.

Findings discovered at levels 7-10 of the multi-level Azikh cave and which entered archaeological literature as Guruchay (the valley where the cave is located) culture, are of special importance in terms of studying the earliest period of human society.

These findings show that the people were hunter gatherers. People’s lives often depended on hunting. Working tools improved from the lower levels upwards. A hearth found at level 6 and dated to 700,000 years ago confirmed that people had learned to make fire. Controlling fire gave a new stimulus to human life. It also enriched people’s spiritual lives and its unprecedented role in human life caused it to be sanctified. This continues in the present- day. Thus, holy places are called “hearths” in Azerbaijan.

A jawbone found at level 5 of the Azikh Palaeolithic camp in 1968, which belonged to homo habilis was a major scientific discovery.

Research established that the bone belonged to a woman aged 18-22 and that it dated to 350,000-400,000 years ago. Thus, people’s material lives and anthropological indicators were documented.

These early human remains have global significance and are called Azikhantrop. Azikhantrops were also engaged in construction and tried to create artificial living places – homes. A bear’s skull found in the Azikh cave has eight slanting lines inscribed on it and gives us some further insight into the mysterious spiritual life of the Azikhantrops. These lines could be a reflection of any thought, number, ritual, picture etc. The fact that such attention was paid to the skull of a bear, and not to other animals, is indicative of early totemism. The parent community ended with the Middle Palaeolithic (100/120 – 40,000 years ago), or Mousterian period, as it is referred to in archaeological literature (after the Le Moustier cave in France). The location of sites belonging to the Middle Palaeolithic (Buzeyir [Lerik District], Gazma [Sharur District], camps on the coast of Lake Orumiyeh etc), indicates the spread of people across the territory of Azerbaij an in that period. The techniques used in making tools were developed, as was their range. Practice in hunting, and improvements in weaponry, made this the main occupation. Hunting became men’s sphere of activity, while the women gathered. Alongside working life, there were also developments in people’s socio-cultural lives. Responsibilities emerged in mutual help and communal living.

The first clan community

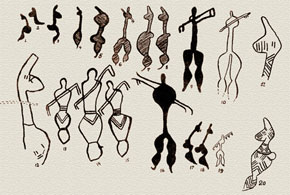

It covers the Upper Palaeolithic period (40,000 years ago – 13th millennium BC) and Mesolithic (Latin: mesos – middle, lithos – stone) age (13th - 8th millennia BC). ‘Wise man’ (Homo sapiens) evolved during the Upper Palaeolithic era. At this time clans emerged, based on blood relationships and common labour, as well as tribes which united several clans. As a result of the high status accorded women in society, clans were defined through the maternal line (matriarchy). It is no accident that archaeological remains from the period depict female figures. Gobustan, a magnificent remainder from Azerbaijan’s Mesolithic Age, brings clarity to a number of questions about human life at the time. Gobustan’s unique feature is the complementary nature of the petroglyphs and rock paintings. There are over 6,000 rock paintings here. Women also comprise a special group in these paintings.

With the invention of the arrow and bow, hunting entered a new phase, thus the large areas given over to hunting scenes and images of hunters at Gobustan. A grave from the late Mesolithic Era was found here. The remains of 10 adults and one child, as well as different tools and ornaments were found in the grave. The mass burial suggests that they died at the same time after some event (poisoning etc). Tools used to weave fishing nets and to fish suggest that they fished. They used boats for fishing. The boats depicted in the Gobustan rock paintings are thought to be some of the most ancient. The famous traveller Thor Heyerdahl (1914-2002) visited Gobustan to examine these paintings several times (1981, 1994 and 1999) and developed a theory that Azer Odi, the ancestor of the Norwegians, was originally from the Caucasus.

The Gobustan rock paintings are a grand gallery of the art of the ancients. The various artworks here provide a complete vision of the artistic taste and aesthetic outlook of the people who lived at that time. UNESCO included Gobustan in its list of “World Cultural Heritage” in 2007.

With the invention of the arrow and bow, hunting entered a new phase, thus the large areas given over to hunting scenes and images of hunters at Gobustan. A grave from the late Mesolithic Era was found here. The remains of 10 adults and one child, as well as different tools and ornaments were found in the grave. The mass burial suggests that they died at the same time after some event (poisoning etc). Tools used to weave fishing nets and to fish suggest that they fished. They used boats for fishing. The boats depicted in the Gobustan rock paintings are thought to be some of the most ancient. The famous traveller Thor Heyerdahl (1914-2002) visited Gobustan to examine these paintings several times (1981, 1994 and 1999) and developed a theory that Azer Odi, the ancestor of the Norwegians, was originally from the Caucasus.

The Gobustan rock paintings are a grand gallery of the art of the ancients. The various artworks here provide a complete vision of the artistic taste and aesthetic outlook of the people who lived at that time. UNESCO included Gobustan in its list of “World Cultural Heritage” in 2007.

Neolithic civilization

The Neolithic (neos – new, lithos – stone) Era in Azerbaij an covers the third quarter of the 8th - 6th millennia BC. This period saw a transition from an appropriating economy to a producing economy. Animals were domesticated, cropping emerged, pottery developed, mud houses were built etc. The Australian archaeologist Vere Gordon Childe (1892-1957) called it the “Neolithic revolution”, in recognition of the importance of this process.

In the new economic conditions during the transition from the appropriating economy, by which humans existed for a very long period of their history, to a producing economy, people’s lives were not as smooth as sometimes described. This era, which was the first major transitional period in human existence, was accompanied by a number of difficulties, which even threatened annihilation. The situation gradually stabilized, however, and areas of production began to realise people’s hopes. Remains from the Neolithic Age have been discovered in the cropping areas of Hasanli, Haji Firuz and Yanigtapa in the basin of Lake Orumiyeh, and in the Anzaga, Kaniza and Hunters’ den camps in Gobustan.

The first cropping tools started to appear in Gobustan and animals were domesticated. A rock painting of a bull with a rope tied around its neck is a reflection of this domestication. Advances in economic life had an impact on social relations and the spiritual world. Although women retained their previous elevated position in society, the role played by men was also developing. A grave found in the Kaniza camp and belonging to the late Neolithic Age gives us some indication. A round stone mace, a stone axe with a polished blade, bone awls etc. were found in the grave, in which two men and one woman were buried. The stone mace is thought to mark the appearance of a community leader. The fact that farming and household items were buried together with the deceased shows that people believed in an afterlife.

In the new economic conditions during the transition from the appropriating economy, by which humans existed for a very long period of their history, to a producing economy, people’s lives were not as smooth as sometimes described. This era, which was the first major transitional period in human existence, was accompanied by a number of difficulties, which even threatened annihilation. The situation gradually stabilized, however, and areas of production began to realise people’s hopes. Remains from the Neolithic Age have been discovered in the cropping areas of Hasanli, Haji Firuz and Yanigtapa in the basin of Lake Orumiyeh, and in the Anzaga, Kaniza and Hunters’ den camps in Gobustan.

The first cropping tools started to appear in Gobustan and animals were domesticated. A rock painting of a bull with a rope tied around its neck is a reflection of this domestication. Advances in economic life had an impact on social relations and the spiritual world. Although women retained their previous elevated position in society, the role played by men was also developing. A grave found in the Kaniza camp and belonging to the late Neolithic Age gives us some indication. A round stone mace, a stone axe with a polished blade, bone awls etc. were found in the grave, in which two men and one woman were buried. The stone mace is thought to mark the appearance of a community leader. The fact that farming and household items were buried together with the deceased shows that people believed in an afterlife.

Collapse of primitive society

The advances in people’s socio-cultural and economic lives were incompatible with primitive society. Early cropping and cattle-breeding are characteristic of the Eneolithic (eneos – copper, lithos – stone) Age (6th - 4th millennia BC). Eneolithic sites are widespread in Azerbaij an. The most well-known are Kultapa (Nakhchivan), Ilanlitapa, Chalagantapa, Leylatapa (Mil-Karabakh), Alikomaktapa (Mugan), Shomutapa, Babadarvish, Gargalartapasi (Ganja-Gazakh), Yanigtapa, Dolmatapa and Goytapa (around Lake Orumiyeh). They are also known as early cropping areas of the “residential hills” type. Sites from this period are also collectively rendered as the Kultapa, Shomutapa and Leylatapa archaeological cultures.

Residential areas in the Eneolithic Age were mainly established along rivers. In the beginning, the houses were built in a round shape and, in the late Eneotlithic Age, in a rectangular shape. As opposed to the Neolithic Age, there was development in the cropping and cattle-breeding areas of agriculture. Bones found in Alikomaktapa confi rm that the horse was domesticated. There were innovations in weaving and pottery, too. Pottery furnaces had now appeared for baking earthenware and potter’s wheels came into use. These technical advances made it possible to produce new types of crockery and to enrich their ornamentation. The arrival of metal manufacture gave rise to metal working. Various tools (awls, needles, knife blades) and ornaments were made from metal.

There was contact between Azerbaijan’s early ploughing population and Mesopotamia. Findings in Azerbaijan have indicated contact between the Khalaf culture (6th millennium BC) and the Ubaid culture (end of 6th millennium – middle of 4th millennium BC). It has also been noted that artefacts were brought here as a result of population migration.

In the Eneolithic Age, too, bigamous family relationships prevailed. Men’s role in society expanded. The geographical range of the stone mace seen earlier also broadened.

People’s spiritual world became richer, with new habits and traditions. The deceased were normally buried where they lived. Ochre was strewn over them. Ornaments and the deceased’s possessions were placed with them in the grave. The construction of special temples was another innovation. A facility in Alikomaktapa, whose walls are plastered with clay and whitewashed, is thought to be a temple. Women’s figures found at various archaeological sites depicted the role they enjoyed in society and also served as symbols of fertility.

Although certain changes in all spheres of life in the Eneolithic Age affected traditional relations, they failed to oust them completely. The softness of copper meant that tools made from it wore out quickly and could not completely replace stone tools.

Bronze, which was obtained by adding antimony, arsenic, nickel and, fi nally, tin to copper, began to fulfil this function. It was in the early stages of the Bronze Age (middle of 4th millennium BC – last quarter of 3rd millennium BC) that primitive community in Azerbaijan entered its final period and its collapse was completed.

In the early Bronze Age, also called the Kur-Araz archaeological culture, clans settled either in a residential area abandoned in the Eneolithic Age (Kultapa, Ovchulartapasi (Nakhchivan), Babadarvish (Gazakh), Goytapa, Yanigtapa (coast of Lake Orumiyeh), or in new places (Garakopaktapa, Gunashtapa (Fuzuli), Gobustan, Mingachevir etc.). Some of the first bronze settlements (Goytapa, Yanigtapa etc) were surrounded by fences. They served as protection against the threat of external attack. There was more innovation in the layout of residential areas, especially in their construction. Two-storey houses were built in the Yanigtapa residential area.

Artificial watering was introduced to cropping. The selection of grain, i.e. the separate planting of barley and wheat, was practised. Finds at Babadarvish confi rm that the collection and storage of wheat improved. A stove found during excavations (Kultapa) provides evidence that bread was baked, too. The development of cattle-breeding gave rise to the fittrst social division of labour – the separation of cattle-breeders from croppers.

The Kur-Araz culture saw further developments in pottery, metal manufacture and metal working. The main change to social life was the replacement of matriarchy by patriarchy. This manifested itself in the appearance of male statues. Barrows were built over men’s graves.

These newly-emerging relationships also revealed themselves in people’s spiritual world. The deceased were buried away from where they lived, so cemeteries were established. Monuments were built for people belonging to the same clan or family. The deceased were usually buried but there were also cases of cremation (Khanlar, Oghuz, and Gabala settlements).

Thus, the pre-state era, or primitive community, which had existed for a long historical period, came to an end and the first states emerged.

Residential areas in the Eneolithic Age were mainly established along rivers. In the beginning, the houses were built in a round shape and, in the late Eneotlithic Age, in a rectangular shape. As opposed to the Neolithic Age, there was development in the cropping and cattle-breeding areas of agriculture. Bones found in Alikomaktapa confi rm that the horse was domesticated. There were innovations in weaving and pottery, too. Pottery furnaces had now appeared for baking earthenware and potter’s wheels came into use. These technical advances made it possible to produce new types of crockery and to enrich their ornamentation. The arrival of metal manufacture gave rise to metal working. Various tools (awls, needles, knife blades) and ornaments were made from metal.

There was contact between Azerbaijan’s early ploughing population and Mesopotamia. Findings in Azerbaijan have indicated contact between the Khalaf culture (6th millennium BC) and the Ubaid culture (end of 6th millennium – middle of 4th millennium BC). It has also been noted that artefacts were brought here as a result of population migration.

In the Eneolithic Age, too, bigamous family relationships prevailed. Men’s role in society expanded. The geographical range of the stone mace seen earlier also broadened.

People’s spiritual world became richer, with new habits and traditions. The deceased were normally buried where they lived. Ochre was strewn over them. Ornaments and the deceased’s possessions were placed with them in the grave. The construction of special temples was another innovation. A facility in Alikomaktapa, whose walls are plastered with clay and whitewashed, is thought to be a temple. Women’s figures found at various archaeological sites depicted the role they enjoyed in society and also served as symbols of fertility.

Although certain changes in all spheres of life in the Eneolithic Age affected traditional relations, they failed to oust them completely. The softness of copper meant that tools made from it wore out quickly and could not completely replace stone tools.

Bronze, which was obtained by adding antimony, arsenic, nickel and, fi nally, tin to copper, began to fulfil this function. It was in the early stages of the Bronze Age (middle of 4th millennium BC – last quarter of 3rd millennium BC) that primitive community in Azerbaijan entered its final period and its collapse was completed.

In the early Bronze Age, also called the Kur-Araz archaeological culture, clans settled either in a residential area abandoned in the Eneolithic Age (Kultapa, Ovchulartapasi (Nakhchivan), Babadarvish (Gazakh), Goytapa, Yanigtapa (coast of Lake Orumiyeh), or in new places (Garakopaktapa, Gunashtapa (Fuzuli), Gobustan, Mingachevir etc.). Some of the first bronze settlements (Goytapa, Yanigtapa etc) were surrounded by fences. They served as protection against the threat of external attack. There was more innovation in the layout of residential areas, especially in their construction. Two-storey houses were built in the Yanigtapa residential area.

Artificial watering was introduced to cropping. The selection of grain, i.e. the separate planting of barley and wheat, was practised. Finds at Babadarvish confi rm that the collection and storage of wheat improved. A stove found during excavations (Kultapa) provides evidence that bread was baked, too. The development of cattle-breeding gave rise to the fittrst social division of labour – the separation of cattle-breeders from croppers.

The Kur-Araz culture saw further developments in pottery, metal manufacture and metal working. The main change to social life was the replacement of matriarchy by patriarchy. This manifested itself in the appearance of male statues. Barrows were built over men’s graves.

These newly-emerging relationships also revealed themselves in people’s spiritual world. The deceased were buried away from where they lived, so cemeteries were established. Monuments were built for people belonging to the same clan or family. The deceased were usually buried but there were also cases of cremation (Khanlar, Oghuz, and Gabala settlements).

Thus, the pre-state era, or primitive community, which had existed for a long historical period, came to an end and the first states emerged.

About the writer:

Karim Shukurov is Doctor of Historical Science at the Institute of History of the Azerbaijani National Academy of Sciences.

Member of the Expert Commission on Historical and Political Sciences of the Appraisal Commission attached to the President of the Azerbaijan Republic.

Member of the Expert Commission on Historical and Political Sciences of the Appraisal Commission attached to the President of the Azerbaijan Republic.