Pages 74-80

By Yagub Mahmudov

Uzun Hasan (1453-1478) of the Aghgoyunlu dynasty was the first ruler in this region to exchange letters and establish relations with the Holy Roman Empire, in the 1470s, when he made military-political alliances with European and Asian states against the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II (1451-1481).

Azerbaijan-European contacts increased in the 16th century. The Safavid Shah Ismayil, who was heavily defeated at the Battle of Chaldiran (1514) by the Ottoman army, turned to many European countries for help. In August 1523 he sent a letter to Emperor Charles V (1519-1556) via the Hungarian ambassador who was visiting the Safavid palace at the time. Shah Ismayil urged the emperor to adopt a policy of war against the Ottoman Empire the following spring, with attacks from both from the west - Europe and from the east - Asia and to prosecute the war to ultimate victory.

But there was no quick or precise reply from the Emperor as he was preoccupied with the long-term war between the Habsburg Empire and France for control of Italy (1494-1559). Only after the war turned in his favour, on 25 August 1525, did Charles reply to the Shah’s letter. However, by the time the letter reached the Safavid palace, Shah Ismayil had been dead for two years. As his son, Shah Tahmasib (1524 - 1576) wanted to maintain peaceful relations with the Ottoman state for some period, he left the Emperor´s letter unanswered.

Relations with European countries were extended during the reign of the most prominent representative of the Safavid dynasty, Shah Abbas (1587-1629). Western envoys visiting the Safavid palace in that period generally passed through Azerbaijan and recorded interesting information in their diaries.

The imperial ambassador visits the Safavid palace, or, Tectander’s record

Shah Abbas, as noted above, endeavoured to expand relations with European states. The struggle against the Ottoman Empire was the political motive while an economic incentive was the search for favourable markets for raw silk, the state’s main export. At his accession to power Shah Abbas inherited deteriorating foreign economic relations. Turkey now dominated communication lines across the Mediterranean and the Black Seas, while access to the Indian Ocean was controlled by Portugal. In these circumstances Shah Abbas dispatched the diplomat Huseynali bey Bayat, with a visiting English envoy, to Europe.

The envoys set off in 1600, going first to Russia. They stayed in Moscow for about six months and then went to the port of Arkhangelsk. The envoys sailed round the Norwegian shores to the mouth of the River Elbe and then on to the palace of the Holy Roman Emperor, which was then in Prague. Emperor Rudolf II (1576-1612) met the Safavid envoys in grand style. Luminaries of the Hapsburgs’ Palace, up to five thousand soldiers and richly decorated phaetons waited at the city’s outskirts to greet them. The emperor organised many official feasts and receptions in honour of Huseynali bey, who stayed in Prague for about six months. After completing successful negotiations with the emperor, the Safavid diplomat left to conduct negotiations with other Western European rulers. In the spring of 1601, Rudolf II gave the envoys an official send-off and presented them many gifts.

Shortly after the envoys had left Prague, the imperial palace decided to send a reciprocal delegation to the palace of Shah Abbas. Stefan Kakash was to head the embassy.

Kakash was a well-educated man. He was a Doctor of Law and a skilful diplomat. Before his dispatch to the Safavid state, Kakash had been ambassador to Poland. But this time Kakash was not fated to complete his final diplomatic mission. He died on his way to Shah Abbas’ palace, near the city of Lenkeran. The embassy’s secretary, Georg von der Jabel Tectander took over Kakash’s mission.

Tectander was similarly learned. He was a German-speaking Czech. At the end of 1604, after completing negotiations with Shah Abbas, he returned to Prague and on 8 January 1605 he reported back officially to Rudolf II. He described his journey to the Safavid state in his book Journey to Persia through Muscovy (1602-1603) and published it in Leipzig in 1608.

Though Tectander called his book Journey to Persia he never actually arrived there. He reached Lenkeran and was then received by Shah Abbas in Tabriz (now capital of the East Azerbaijan province in Iran - ed). He then left for Nakhchivan and Irevan, with Safavid military forces fighting the Ottomans. Thus, although the ambassador saw little of Persian society, he travelled substantially through Azerbaijani lands.

Tectander wrote at the very beginning of his diary that their journey was in response to the embassy of Huseynali bey sent by Shah Abbas to Germany in 1600. This information is valuable evidence that Huseynali bey Bayat did conduct negotiations at the Hapsburgs’ Palace.

The two-year mission begins….

The envoys set off from Prague on 27 August 1602, arrived in Moscow on 6 November and were received by Tsar Boris Godunov on 27 November. They stayed in Moscow for some four weeks and left for the Safavid palace on 7 December 1602. They arrived in Kazan on 24 December and wintered here. On 11 May 1603 the envoys resumed their journey, reaching Astrakhan on 27 May. They remained there for about two months and on 22 July 1603 boarded, Tectander wrote, a merchant ship belonging to the Safavid state. Tectander’s journal describing events after Astrakhan is of key interest in as much as they concerned Azerbaijan. When they entered the Caspian Sea from the River Volga he wrote that the sea was two days’ distance from Astrakhan and was 300 German miles in width.

Emperor Rudolf’s envoys arrived at Lenkeran on 8 August 1603. Tectander wrote:

Lenkeran is one mile from the sea. This place is beautiful and has a pleasing appearance. However, because it is very hot and close to the sea, its air is not healthy. We stayed there approximately ten weeks. We ate tasteless lamb and rice bread. Grapes and other fruits grow in abundance here. However, the ‘Iranians’ (Azerbaijanis-Y.M.) cannot make wine. They do not drink any. They simply eat the grapes.

The mission was not allowed to move from Lenkeran until permission was issued by Shah Abbas. Thus, Kakash’s men were marooned for ten weeks, waiting for the Shah’s response. This period was a real disaster for the Europeans. Tectander wrote that during this time:

all of us - my master (Kakash-Y.M.) and 8 people who were with us fell ill. First Pavlovsky, the noble ambassador of Poland, died.

Members of the embassy died one by one. Kakash was at death’s door and so he sent a messenger to the Shah asking for an urgent reception. Meanwhile, Shah Abbas had already begun a war against the Ottoman Empire, winning battles from Isfahan to Tabriz. He decided to receive the envoys in Tabriz and sent the English diplomat Robert Shirley, who was staying in the Safavid palace, to Lenkeran to take the emperor’s envoys to Tabriz. Tectander wrote that it was only possible to carry Kakash two miles on a stretcher. He died on 25 October 1603 and was buried the next day, under the tree in the yard of the house where they were staying.

Tectander in Tabriz….

In his official will, Kakash charged Tectander with completing the diplomatic mission. On 26 October 1603 Tectander left Lenkeran and when he reached Qazvin on 1 November only three members of the embassy - himself, Georg Agelast and a servant survived. Then Agelast died in Qazvin and Georg Tectander had to fulfil Emperor Rudolf’s mission almost alone. He left Qazvin and went directly to Tabriz to meet Shah Abbas, arriving in the ancient Azerbaijani city on 15 November 1603.

As the traveller wrote, the Shah had driven Ottoman troops out of Tabriz twelve days prior to his arrival, on 3 November 1603. Hardly had the envoy got off his horse when the Safavid ruler summoned him. In describing his reception by Shah Abbas, Tectander indicated that the Safavids also maintained diplomatic relations with Italy. He noted that the Shah was sitting with all his courtiers and advisors during the reception:

The Shah was dressed worse than the others, so that I did not even recognize him. I remained speechless as my interpreter was not with me. Then an old ‘Iranian’ took me to the Shah´s presence. I dropped down on my knees... At that moment an Italian spoke to me in Italian. I told him, in Latin, everything that had happened to us. When Shah Abbas asked me the reason for my visit and requested letters I could not submit them because he had received me immediately on my arrival in Tabriz and I had not had time even to change my clothes. I had left the documents and other items at the place I was staying. At that, the Shah sent someone to fetch the letters.

As Tectander wrote, he had brought three letters for Shah Abbas. Two of them - one in Latin and the other in Italian - were written by Emperor Rudolf II, the third letter was from the ‘Grand Prince of Muscovy’ (the tsar - ed). The Shah instructed that the Emperor’s letter, written in Italian, be translated into Persian and thus the Safavid ruler was informed about Rudolf’s plans.

Shah Abbas did not stay long in Tabriz; he left three days after receiving Tectander. He was fighting to reclaim lands previously conquered by the Ottoman Empire. After capturing Tabriz he did not want to give the defeated Ottoman troops time to recover.

Tectander himself left with Shah Abbas’ troops. The envoy was a first-hand witness of this period in the Safavid-Ottoman wars and had the opportunity to study Safavid life style in some depth.

Even though his stay was a short one, Tectander provided very interesting information about Tabriz. In his overall impression of the city, he wrote:

Tabriz is a very big city with beautiful houses decorated in Turkic (i.e. Azerbaijani – Y.M.) style, gardens, mosques and bathhouses... The walls of the mosques are covered with Turkic inscriptions.

He recorded that Shah Abbas had an army of 120,000 to oppose the Ottomans. Following the liberation of Azerbaijani regions he wrote that people greeted Shah Abbas as a saviour.

….and Nakhchivan

While moving with the troops from Tabriz to Nakhchivan, Tectander noted that in those regions:

the educational level of the population of these places remains as it was many years ago; they don’t have their own printing houses, all books are written as manuscripts. However, they have a good knowledge of history and it is impossible to tell them anything about their ancestors that they are not aware of.

He witnessed Shah Abbas’ capture of Nakhchivan and Julfa and recorded everyday Azerbaijani life in detail.

everyone washes their hands before a meal and sits on a carpet on the ground with their legs folded.

He commented on the most beautiful carpets spread on the floor during dinner. As for the meals, he reported that the food, in most cases, consisted of thickly cooked rice, in other words pilaf, dressed with ash garasi (spicy, roasted meat with various dried fruits) and fried poultry, partridge and pheasant, as well as lamb and horse meat served with rice. He also noticed that there was a difference between the meals served to the Shah: while the monarch was served three or four dishes, others were served only one. Syrup was always distributed after a meal; drinking wine was prohibited, under pain of death.

Tectander explained very simply the reasons for the presence of European envoys in the Safavid palace and the Shah’s benevolent attitude towards them: He treats Christians with great respect.

The envoy was also present at the recapture of Irevan. However, following this success, Shah Abbas sent him back with a letter informing Emperor Rudolf of his military achievements and with valuable gifts. This time, the shah’s envoy Mehdiqulu bey was to accompany him to Europe to conduct negotiations with the rulers of Western Europe.

On his way back from Derbend, Tectander wrote:

When I was returning after conducting negotiations with Shah Abbas near Derbend I met the Safavid ambassador coming back from Moscow. He said that the Grand Prince had sent a few thousand men, including several skilled artillerymen and a couple of big guns to his sovereign in order to besiege Derbend and get it back from the Turks. The Grand Prince encouraged the Iranian Shah (Safavid ruler – Y.M.) to start a war against the Turks.

This note clearly shows that the tsar already had strategic plans for the region.

Mehdigulu bey and Tectander, who went on to Moscow from Derbend, were received by Tsar Boris Godunov and they informed him of Shah Abbas’ military achievements. The tsar gave them a letter for Emperor Rudolf II.

The envoys went from Moscow to the shores of the Baltic and from there to Prague to be received by Rudolf II. The Safavid envoys were well-received in the Emperor’s palace and negotiations were successful. Moreover, from 1604-1605 the artist Aegidius Sadeler painted a portrait of Zeynal khan Shamlu, one of the Safavid envoys under Mehdigulu bey, while they were in Prague.

Relations with the Dukedom of Holstein, or, Adam Olearius on Azerbaijan

Adam Olearius was a German writer who left us very interesting information about Azerbaijan. He was a distinguished scientist in his day (1599-1671), having graduated from Leipzig University. Besides history, he was well-read in astronomy, mathematics, physics and geography. He worked at the university as assistant to the rector from 1630-1633 before finally serving in the palace of the Duke of Holstein, ruler of one of the small German feudal states. Duke Frederick III (1616-1659) included Olearius in a Holstein embassy dispatched to Moscow and the Safavid state to conduct negotiations. He began as secretary to the embassy, later serving as a counsellor.

He studied the eastern languages during his travels, collected much information about the geography and historical monuments, events and ceremonies he witnessed and returned to Germany with precious manuscripts and samples of men´s and women´s national costumes. Upon his return home he wrote a journal, compiled an Arabic–Persian–Turkish dictionary and translated Sa’di’s poem Gulustan into German.

The Holstein embassy obtained official permission from the tsar to cross Russian territory to the Safavid state on 20 June 1636 and left Moscow on 30 June. They reached Nizhny Novgorod on 11 July and boarded the ship Frederick. By 15 September, the envoys were already in Astrakhan.

A first taste of Shemakha

The traveller found much of interest in that city, including the excellent grapes of almost walnut-size. He wrote, however, that the grapes were not originally grown there. The first vines had been taken to Astrakhan by Azerbaijani merchants – from Shemakha.

An old monk planted them in the yard of the old cloister before the city. As the grapevines started to grow, the Grand Prince ordered, in 1613, that a proper vineyard be laid out. This vineyard expanded year by year. Some of the excellent large, sweet grapes grown in the vineyard are sent to Moscow for the Grand Prince, while others are sold to voivodes (generals) and boyars.

Olearius, like other European travellers, noted the importance of Azerbaijani merchants to Astrakhan trade.

He also noted evidence of the Safavid state’s diplomatic relations. On 22 September the Holsteins met the Polish ambassador, who was on his way back from negotiations at the Safavid Palace, and the Safavid diplomat who was travelling with him to Poland. On 13 November 1636, the Frederick, which had been badly damaged by storms and had lost its life boats, was held up for three days, moored in Niyazabad. We should note that Olearius gave the exact name of the first settlement he met in Azerbaijan – Niyazabad; he said it was known as Nizovoy in his own homeland. As there were no small boats on the ship, the Holstein envoys were only able to step onto dry land the next day, on 14 November.

Caspian, oil and fish

The first detailed information Olearius gave about Azerbaijan was about the Caspian Sea. He records that it had different names (Khazar, Tabaristan, Gulzum, Hirkan, Caspian, Baku, Khvalin etc.) at different times. He criticized the ancient geographers who had claimed wrongly that the Caspian Sea was circular in shape and connected to the ocean.

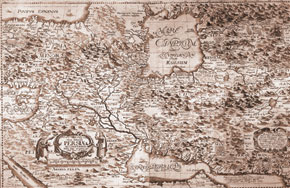

He drew a map of the sea from personal observation and challenged the structure of existing maps. Of previous cartographers, he said that the error of one brings about errors by others.

He took a further step towards improving maps of the sea in noticing that there was no ebb and flow. He wrote that many rivers flowed into the Caspian, indicating that on the way back from Isfahan, during the short trip from Rasht to Shemakha we crossed at least 80 large and small rivers.

He named the confluent Kura and Araz rivers, the Giziluzan River and others.

He disputed the views of previous writers that Caspian Sea islands were well-populated and had many beautiful cities.

Of course he reported on the phenomenon of natural oil:

This petroleum is a special kind of oil. Around Baku and near Barmakh Mountain (Besh Barmaq – Y.M.) it is produced from permanent springs in large amounts, poured into wineskins and delivered to various parts of the country on large carts for sale.

Olearius also wrote that the Caspian Sea was rich in fish resources of every kind.

The envoys had to stay near Niyazabad for more than five weeks until 22 December. During this period, Olearius got to know a little about the environment in Azerbaijan and people’s lifestyles. He described the area as a province of Shirvan, a part of it, writing that this coastal strip of Azerbaijan,

Even in December

starts from Derbend and extends to Gilan along the coast; there are 200 villages. Every turn of this country has a very pleasing appearance, the grass and trees are still green (in November and December! – Y.M.); the land is fertile and productive. The whole region is rich in rice, wheat and barley, as well as nice fruit. This country is full of trees of various kinds and also has thin forests, so birds sing merry songs here even in December.

On 22 December 1636 the Holstein envoys departed for Shemakha with their long caravan of 40 camels, 30 carts and 80 horses. As there was a shortage of pack and riding animals in the caravan, servants, service staff and soldiers had to walk. Heading south along the Caspian Sea coast, the caravan stayed over in a village called Mardov by Olearius. He noticed a kinship between the local population and the Tatars living near Astrakhan. He described the local population as living in round houses built of cane and twigs. It is interesting that as soon as Olearius stepped onto Azerbaijani territory he began learning the language. He tried to give everything that attracted his attention its Azerbaijani name.

He made notes about ‘Barmakh’ Mountain seen on the caravan’s journey from Niyazabad to Shemakha. They approached the high Besh Barmaq rock on 24 December. Writing about the medieval caravanserai there he noted that as soon as we arrived we entered the ‘open yard’ at the foot of the mountain. This was one of many such ‘yards’ and ‘shelters’ Olearius encountered in the country - a clear indication of the development of trade, including foreign trade relations.

As though we were in a paradise….

On 26 December 1636, on a sunny day, the caravan left the Besh Barmaq caravanserai, skirted Baku and made for Shemakha, which it reached on 30 December.

They were well received. The Shirvan beylerbeyi (governor) organised an official greeting for the guests. Still on the outskirts of Shemakha, Olearius realised that the country which he had referred to as ‘Iran’ was not Iran at all. He was impressed by the welcome from the beylerbeyi’s troop at the entrance to the city:

The cavalry bowed before the envoys, and greeted them with a loud ‘welcome’ in Turkish. They talk in Turkish more willingly than in Persian.

Olearius also turned his attention to the musical instruments he came across, recording the names of the unfamiliar ones. He wrote that:

we heard the war music of this strange country. Four musicians preceded us. They played a copper instrument resembling a tutek, 4 gulaj (equal to the length from fingertip to fingertip of outstretched arms) long and with a bell end. This instrument was called a garaney (the ney is a kind of end-blown flute). It was played by holding it up to the sky. There were also players of ordinary pipes and a few drummers among the musicians. They hung their oblong drums, resembling pots, over their saddles…. Some of the instruments resembled long, curved horns, there were tambourines and others among the people greeting us. The city’s population welcomed us with applause, waving and tossing up their hats, with cheering and great joy.

At the magnificent reception arranged by the Shirvan beylerbeyi, the traveller´s attention was drawn to the bread half a gulaj in size and as thin as parchment, brought on large, deep wooden plates, full to the brim. The local people called this bread yukha and a waiter was addressed as sufrechi. Olearius wrote that the dinner was conducted with absolute cleanliness and tidiness...

Today we enjoyed such luxury - as though we were in a paradise of this world.

The Holstein envoys stayed in Shemakha for three months. The German writer studied the city thoroughly, collecting a wealth of material about the people and their land. Indeed, the most interesting and valuable facts in his travelogue illustrated his stay in Shemakha.

Winter over, the caravan left the city on 27 March 1637. Walking down the Shemakha Mountains, Olearius described the inimitable view which opened up before his eyes: fertile plains, deep green slopes, peaks reaching to the skies through snowy-white clouds. In the lowlands the travellers were hosted in their winter quarters by herdsmen who met them kindly and allocated a few ‘rooms’ for their foreign guests.

Ardebil provides

On 31 March, the party reached the banks of the River Kur at Javad village. Observations noted that the Kura and Araz Rivers, flowing quietly, were 140 paces wide and deep. There was information about the Mugan region. We learn that a lot of liquorice was grown, sometimes very thickly, in the meadows on the banks of the Kur. The juice, Olearius wrote, was sweeter and more pleasing than the German variety.

On 2 April the visitors crossed the Kur by the ‘raft’ bridge there and were met by one of the Ardebil khan’s innkeepers. 40 camels and about 300 horses were waiting for the foreign envoys. Provisions had also been prepared for their onward journey: 10 sheep per day, 30 batman (1 batman = 5 kgs) of wine, a lot of rice, butter, eggs, almonds, raisins, apples etc.

From Mugan to Ardebil the travellers passed beautiful orchards, witnessed the construction of a big caravanserai for the East Indian company which trades with Shemakha and crossed the six-arched, 80-pace long, graceful stone bridge over the Garasu River; they reached Ardebil on 10 April 1637.

Olearius wrote interestingly about Ardebil, noting that the name of this ancient city was Turkic and it was situated in Azerbaijan province. Also in the province, he wrote, were Tabriz, Nakhichevan, Marand, Urmiya, Khoy and Salmas. He explained the city’s fame as the burial place of the Safavids; agreed with the belief that the British had a residence here for a while during their attack on Iran; and finally, he noted that the city was a trade centre of great importance to the local population and foreigners. His remark that the people of Ardebil usually speak in a Turkic language (Azerbaijani – Y.M.) is also valuable historical information.

The Holstein embassy stayed in the city for two months, leaving on 12 June. Ardebil’s architectural monuments, rich artistic and commercial life and hospitality made a deep impression and were written into a fascinating memoir.

The Safavid ruler, Shah Safi, received the envoys in Isfahan on 16 August and Duke Frederick’s gifts were presented to him. Olearius’ account of the reception indicates that Azerbaijani was spoken in the palace, even at official events, as far back as the 17th century. On 16 August 1637, after a one and a half hour feast given in the envoys’ honour, the Great Marshal intoned a blessing of the meal in Azerbaijani:

Toasting the meal,

The Shah’s state,

The strength of the Gazis (fighters for the faith – Y.M.)

Glorify Allah

The Holstein envoys were by no means the only Europeans at the home of the Safavid court:

After the open presentation, various foreigners living in Isfahan: Englishmen, Portuguese, Italians and Frenchmen began to visit us.

The Safavid state

Olearius gave a lengthy description of the Safavid state in the Isfahan section of his journal. He divided the state into five main provinces; three of the five cover Azerbaijani territory: Shirvan, Aran and Azerbaijan, and each province was described in turn. The return journey saw the envoys reach Astara at the beginning of February 1638. Here they saw grapevines as thick as the human body, thus confirming the ancient account given by the Greek geographer Strabo. He also wrote:

The inhabitants of Astara always keep their arms in readiness.

Cossack robbers operating in the lower reaches of the Volqa also attacked the coastal regions of Azerbaijan, including Astara, for plunder, taking everything came to their hands.

On 7 February in Lenkeran, the traveller investigated the origin of the place name, noting that langar was a place where an anchor was dropped - a harbour. He recalled here the death and burial in 1603 of Stefan Kakash, Emperor Rudolf’s ambassador.

The caravan arrived at Gizilaghaj on 11 February. Olearius wrote that there was an island here, well offshore. The colour of its earth earned it the local name Yellow Island. It was long recorded on maps as Sarah Island (in Azerbaijani sari = yellow – ed.) He also wrote that the name of Gizilaghaj was a combination of two words gizil = gold/red and aghaj = tree. He was struck by the meadow here, whose limits were not seen with the naked eye.

Back in Mugan on 12 February, the envoys stayed again in one of the ‘hamlets’ built by herdsmen. Further notes were added to the diary: in a region more than 60 miles long and 20 miles wide, there lived very many tribes and generations; he named a number of them. The population of Mugan was engaged in livestock farming and there were winter and summer lives:

In summer they go to the mountains, where there are the best pastures and picturesque uplands. In winter they set up camps in a flat desert.

Hosted all along the way, the caravan returned to Shemakha on 20 February 1638, staying there until 30 March and the arrival of spring. Passing Besh Barmaq Mountain on 2 April, the travellers then saw oil springs near the sea:

They are pits, up to 30 different kinds, located almost a rifle shot apart. Oil spurts strongly from them... The three main springs here go down to a depth of 2 sazhens (1 sazhen = 2.34 metres)... The eruption of the oil from these springs was heard from above, as if they were boiling; their smell is much stronger. By the way, compared with the smell of the brown oil, kerosene oil is more pleasant. It is possible to extract both brown oil and kerosene oil from here, but there is more of the first than the second.

Circassian and Russian merchants, who were returning from their trade in Shemakha, joined the Holstein envoys near Niyazabad. They spent the night in a nearby village:

We found many excellent books in manuscript in the home of the confessor where we were hosted.

Crowded caravan

The envoys reached the ancient city of Derbend on 7 April and stayed there for just five days. However, Olearius got down to a thorough study of the city and its historical monuments.

He even drew a map to give a better impression of the city; he then described it sector by sector and recorded some of the legends of the Oghuz people

As the visitors departed the Safavid state there were 52 rifles, 38 pistols, 6 guns accompanying the caravan’s complement of 300 cooks, doctors, diplomats and others. They were returning with a rare collection of silk fabrics, a variety of jewellery in gold and precious stones, carpets, spices, morocco and other goods from Azerbaijan to far Holstein. Azerbaijanis were with them, on their way to trade in distant lands; Russians returning from their own trading missions and merchants of various nations had also joined the enormous trade caravan sailing to Astrakhan.

By 2 January 1639 they were back in Moscow. The Safavid diplomat Imamgulu sultan, travelling to European countries, followed them there. On 5 February he was welcomed by the Tsar’s retinue at entrance to Moscow,

The Russians delivered him to the city in great luxury; so as not to detain us, the tsar received him within three days.

On 7 March, Imamqulu sultan left Moscow and went along the Tver-Novgorod-Narva-Reval route to the Baltic Sea coast, rejoining the caravan on 11 July. He and the Holstein envoys finally completed their epic journey, arriving at Duke Frederick’s residence in Gottorp on 1 August 1639….

Literature

1. Y. Mahmudov. Journey to the Land of Fires. Baku, 1980

2. Kakash and Tectander. Journey to Persia through Muscovy, 1602-1603. Translated from German. M., 1896

3. Adam Olearius. Description of a Journey to Muscovy and Through Muscovy to Persia and Back. Saint-Petersburg, 1906

By Yagub Mahmudov

Uzun Hasan (1453-1478) of the Aghgoyunlu dynasty was the first ruler in this region to exchange letters and establish relations with the Holy Roman Empire, in the 1470s, when he made military-political alliances with European and Asian states against the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II (1451-1481).

Azerbaijan-European contacts increased in the 16th century. The Safavid Shah Ismayil, who was heavily defeated at the Battle of Chaldiran (1514) by the Ottoman army, turned to many European countries for help. In August 1523 he sent a letter to Emperor Charles V (1519-1556) via the Hungarian ambassador who was visiting the Safavid palace at the time. Shah Ismayil urged the emperor to adopt a policy of war against the Ottoman Empire the following spring, with attacks from both from the west - Europe and from the east - Asia and to prosecute the war to ultimate victory.

But there was no quick or precise reply from the Emperor as he was preoccupied with the long-term war between the Habsburg Empire and France for control of Italy (1494-1559). Only after the war turned in his favour, on 25 August 1525, did Charles reply to the Shah’s letter. However, by the time the letter reached the Safavid palace, Shah Ismayil had been dead for two years. As his son, Shah Tahmasib (1524 - 1576) wanted to maintain peaceful relations with the Ottoman state for some period, he left the Emperor´s letter unanswered.

Relations with European countries were extended during the reign of the most prominent representative of the Safavid dynasty, Shah Abbas (1587-1629). Western envoys visiting the Safavid palace in that period generally passed through Azerbaijan and recorded interesting information in their diaries.

The imperial ambassador visits the Safavid palace, or, Tectander’s record

Shah Abbas, as noted above, endeavoured to expand relations with European states. The struggle against the Ottoman Empire was the political motive while an economic incentive was the search for favourable markets for raw silk, the state’s main export. At his accession to power Shah Abbas inherited deteriorating foreign economic relations. Turkey now dominated communication lines across the Mediterranean and the Black Seas, while access to the Indian Ocean was controlled by Portugal. In these circumstances Shah Abbas dispatched the diplomat Huseynali bey Bayat, with a visiting English envoy, to Europe.

The envoys set off in 1600, going first to Russia. They stayed in Moscow for about six months and then went to the port of Arkhangelsk. The envoys sailed round the Norwegian shores to the mouth of the River Elbe and then on to the palace of the Holy Roman Emperor, which was then in Prague. Emperor Rudolf II (1576-1612) met the Safavid envoys in grand style. Luminaries of the Hapsburgs’ Palace, up to five thousand soldiers and richly decorated phaetons waited at the city’s outskirts to greet them. The emperor organised many official feasts and receptions in honour of Huseynali bey, who stayed in Prague for about six months. After completing successful negotiations with the emperor, the Safavid diplomat left to conduct negotiations with other Western European rulers. In the spring of 1601, Rudolf II gave the envoys an official send-off and presented them many gifts.

Shortly after the envoys had left Prague, the imperial palace decided to send a reciprocal delegation to the palace of Shah Abbas. Stefan Kakash was to head the embassy.

Kakash was a well-educated man. He was a Doctor of Law and a skilful diplomat. Before his dispatch to the Safavid state, Kakash had been ambassador to Poland. But this time Kakash was not fated to complete his final diplomatic mission. He died on his way to Shah Abbas’ palace, near the city of Lenkeran. The embassy’s secretary, Georg von der Jabel Tectander took over Kakash’s mission.

Tectander was similarly learned. He was a German-speaking Czech. At the end of 1604, after completing negotiations with Shah Abbas, he returned to Prague and on 8 January 1605 he reported back officially to Rudolf II. He described his journey to the Safavid state in his book Journey to Persia through Muscovy (1602-1603) and published it in Leipzig in 1608.

Though Tectander called his book Journey to Persia he never actually arrived there. He reached Lenkeran and was then received by Shah Abbas in Tabriz (now capital of the East Azerbaijan province in Iran - ed). He then left for Nakhchivan and Irevan, with Safavid military forces fighting the Ottomans. Thus, although the ambassador saw little of Persian society, he travelled substantially through Azerbaijani lands.

Tectander wrote at the very beginning of his diary that their journey was in response to the embassy of Huseynali bey sent by Shah Abbas to Germany in 1600. This information is valuable evidence that Huseynali bey Bayat did conduct negotiations at the Hapsburgs’ Palace.

The two-year mission begins….

The envoys set off from Prague on 27 August 1602, arrived in Moscow on 6 November and were received by Tsar Boris Godunov on 27 November. They stayed in Moscow for some four weeks and left for the Safavid palace on 7 December 1602. They arrived in Kazan on 24 December and wintered here. On 11 May 1603 the envoys resumed their journey, reaching Astrakhan on 27 May. They remained there for about two months and on 22 July 1603 boarded, Tectander wrote, a merchant ship belonging to the Safavid state. Tectander’s journal describing events after Astrakhan is of key interest in as much as they concerned Azerbaijan. When they entered the Caspian Sea from the River Volga he wrote that the sea was two days’ distance from Astrakhan and was 300 German miles in width.

Emperor Rudolf’s envoys arrived at Lenkeran on 8 August 1603. Tectander wrote:

Lenkeran is one mile from the sea. This place is beautiful and has a pleasing appearance. However, because it is very hot and close to the sea, its air is not healthy. We stayed there approximately ten weeks. We ate tasteless lamb and rice bread. Grapes and other fruits grow in abundance here. However, the ‘Iranians’ (Azerbaijanis-Y.M.) cannot make wine. They do not drink any. They simply eat the grapes.

The mission was not allowed to move from Lenkeran until permission was issued by Shah Abbas. Thus, Kakash’s men were marooned for ten weeks, waiting for the Shah’s response. This period was a real disaster for the Europeans. Tectander wrote that during this time:

all of us - my master (Kakash-Y.M.) and 8 people who were with us fell ill. First Pavlovsky, the noble ambassador of Poland, died.

Members of the embassy died one by one. Kakash was at death’s door and so he sent a messenger to the Shah asking for an urgent reception. Meanwhile, Shah Abbas had already begun a war against the Ottoman Empire, winning battles from Isfahan to Tabriz. He decided to receive the envoys in Tabriz and sent the English diplomat Robert Shirley, who was staying in the Safavid palace, to Lenkeran to take the emperor’s envoys to Tabriz. Tectander wrote that it was only possible to carry Kakash two miles on a stretcher. He died on 25 October 1603 and was buried the next day, under the tree in the yard of the house where they were staying.

Tectander in Tabriz….

In his official will, Kakash charged Tectander with completing the diplomatic mission. On 26 October 1603 Tectander left Lenkeran and when he reached Qazvin on 1 November only three members of the embassy - himself, Georg Agelast and a servant survived. Then Agelast died in Qazvin and Georg Tectander had to fulfil Emperor Rudolf’s mission almost alone. He left Qazvin and went directly to Tabriz to meet Shah Abbas, arriving in the ancient Azerbaijani city on 15 November 1603.

As the traveller wrote, the Shah had driven Ottoman troops out of Tabriz twelve days prior to his arrival, on 3 November 1603. Hardly had the envoy got off his horse when the Safavid ruler summoned him. In describing his reception by Shah Abbas, Tectander indicated that the Safavids also maintained diplomatic relations with Italy. He noted that the Shah was sitting with all his courtiers and advisors during the reception:

The Shah was dressed worse than the others, so that I did not even recognize him. I remained speechless as my interpreter was not with me. Then an old ‘Iranian’ took me to the Shah´s presence. I dropped down on my knees... At that moment an Italian spoke to me in Italian. I told him, in Latin, everything that had happened to us. When Shah Abbas asked me the reason for my visit and requested letters I could not submit them because he had received me immediately on my arrival in Tabriz and I had not had time even to change my clothes. I had left the documents and other items at the place I was staying. At that, the Shah sent someone to fetch the letters.

As Tectander wrote, he had brought three letters for Shah Abbas. Two of them - one in Latin and the other in Italian - were written by Emperor Rudolf II, the third letter was from the ‘Grand Prince of Muscovy’ (the tsar - ed). The Shah instructed that the Emperor’s letter, written in Italian, be translated into Persian and thus the Safavid ruler was informed about Rudolf’s plans.

Shah Abbas did not stay long in Tabriz; he left three days after receiving Tectander. He was fighting to reclaim lands previously conquered by the Ottoman Empire. After capturing Tabriz he did not want to give the defeated Ottoman troops time to recover.

Tectander himself left with Shah Abbas’ troops. The envoy was a first-hand witness of this period in the Safavid-Ottoman wars and had the opportunity to study Safavid life style in some depth.

Even though his stay was a short one, Tectander provided very interesting information about Tabriz. In his overall impression of the city, he wrote:

Tabriz is a very big city with beautiful houses decorated in Turkic (i.e. Azerbaijani – Y.M.) style, gardens, mosques and bathhouses... The walls of the mosques are covered with Turkic inscriptions.

He recorded that Shah Abbas had an army of 120,000 to oppose the Ottomans. Following the liberation of Azerbaijani regions he wrote that people greeted Shah Abbas as a saviour.

….and Nakhchivan

While moving with the troops from Tabriz to Nakhchivan, Tectander noted that in those regions:

the educational level of the population of these places remains as it was many years ago; they don’t have their own printing houses, all books are written as manuscripts. However, they have a good knowledge of history and it is impossible to tell them anything about their ancestors that they are not aware of.

He witnessed Shah Abbas’ capture of Nakhchivan and Julfa and recorded everyday Azerbaijani life in detail.

everyone washes their hands before a meal and sits on a carpet on the ground with their legs folded.

He commented on the most beautiful carpets spread on the floor during dinner. As for the meals, he reported that the food, in most cases, consisted of thickly cooked rice, in other words pilaf, dressed with ash garasi (spicy, roasted meat with various dried fruits) and fried poultry, partridge and pheasant, as well as lamb and horse meat served with rice. He also noticed that there was a difference between the meals served to the Shah: while the monarch was served three or four dishes, others were served only one. Syrup was always distributed after a meal; drinking wine was prohibited, under pain of death.

Tectander explained very simply the reasons for the presence of European envoys in the Safavid palace and the Shah’s benevolent attitude towards them: He treats Christians with great respect.

The envoy was also present at the recapture of Irevan. However, following this success, Shah Abbas sent him back with a letter informing Emperor Rudolf of his military achievements and with valuable gifts. This time, the shah’s envoy Mehdiqulu bey was to accompany him to Europe to conduct negotiations with the rulers of Western Europe.

On his way back from Derbend, Tectander wrote:

When I was returning after conducting negotiations with Shah Abbas near Derbend I met the Safavid ambassador coming back from Moscow. He said that the Grand Prince had sent a few thousand men, including several skilled artillerymen and a couple of big guns to his sovereign in order to besiege Derbend and get it back from the Turks. The Grand Prince encouraged the Iranian Shah (Safavid ruler – Y.M.) to start a war against the Turks.

This note clearly shows that the tsar already had strategic plans for the region.

Mehdigulu bey and Tectander, who went on to Moscow from Derbend, were received by Tsar Boris Godunov and they informed him of Shah Abbas’ military achievements. The tsar gave them a letter for Emperor Rudolf II.

The envoys went from Moscow to the shores of the Baltic and from there to Prague to be received by Rudolf II. The Safavid envoys were well-received in the Emperor’s palace and negotiations were successful. Moreover, from 1604-1605 the artist Aegidius Sadeler painted a portrait of Zeynal khan Shamlu, one of the Safavid envoys under Mehdigulu bey, while they were in Prague.

Relations with the Dukedom of Holstein, or, Adam Olearius on Azerbaijan

Adam Olearius was a German writer who left us very interesting information about Azerbaijan. He was a distinguished scientist in his day (1599-1671), having graduated from Leipzig University. Besides history, he was well-read in astronomy, mathematics, physics and geography. He worked at the university as assistant to the rector from 1630-1633 before finally serving in the palace of the Duke of Holstein, ruler of one of the small German feudal states. Duke Frederick III (1616-1659) included Olearius in a Holstein embassy dispatched to Moscow and the Safavid state to conduct negotiations. He began as secretary to the embassy, later serving as a counsellor.

He studied the eastern languages during his travels, collected much information about the geography and historical monuments, events and ceremonies he witnessed and returned to Germany with precious manuscripts and samples of men´s and women´s national costumes. Upon his return home he wrote a journal, compiled an Arabic–Persian–Turkish dictionary and translated Sa’di’s poem Gulustan into German.

The Holstein embassy obtained official permission from the tsar to cross Russian territory to the Safavid state on 20 June 1636 and left Moscow on 30 June. They reached Nizhny Novgorod on 11 July and boarded the ship Frederick. By 15 September, the envoys were already in Astrakhan.

A first taste of Shemakha

The traveller found much of interest in that city, including the excellent grapes of almost walnut-size. He wrote, however, that the grapes were not originally grown there. The first vines had been taken to Astrakhan by Azerbaijani merchants – from Shemakha.

An old monk planted them in the yard of the old cloister before the city. As the grapevines started to grow, the Grand Prince ordered, in 1613, that a proper vineyard be laid out. This vineyard expanded year by year. Some of the excellent large, sweet grapes grown in the vineyard are sent to Moscow for the Grand Prince, while others are sold to voivodes (generals) and boyars.

Olearius, like other European travellers, noted the importance of Azerbaijani merchants to Astrakhan trade.

He also noted evidence of the Safavid state’s diplomatic relations. On 22 September the Holsteins met the Polish ambassador, who was on his way back from negotiations at the Safavid Palace, and the Safavid diplomat who was travelling with him to Poland. On 13 November 1636, the Frederick, which had been badly damaged by storms and had lost its life boats, was held up for three days, moored in Niyazabad. We should note that Olearius gave the exact name of the first settlement he met in Azerbaijan – Niyazabad; he said it was known as Nizovoy in his own homeland. As there were no small boats on the ship, the Holstein envoys were only able to step onto dry land the next day, on 14 November.

Caspian, oil and fish

The first detailed information Olearius gave about Azerbaijan was about the Caspian Sea. He records that it had different names (Khazar, Tabaristan, Gulzum, Hirkan, Caspian, Baku, Khvalin etc.) at different times. He criticized the ancient geographers who had claimed wrongly that the Caspian Sea was circular in shape and connected to the ocean.

He drew a map of the sea from personal observation and challenged the structure of existing maps. Of previous cartographers, he said that the error of one brings about errors by others.

He took a further step towards improving maps of the sea in noticing that there was no ebb and flow. He wrote that many rivers flowed into the Caspian, indicating that on the way back from Isfahan, during the short trip from Rasht to Shemakha we crossed at least 80 large and small rivers.

He named the confluent Kura and Araz rivers, the Giziluzan River and others.

He disputed the views of previous writers that Caspian Sea islands were well-populated and had many beautiful cities.

Of course he reported on the phenomenon of natural oil:

This petroleum is a special kind of oil. Around Baku and near Barmakh Mountain (Besh Barmaq – Y.M.) it is produced from permanent springs in large amounts, poured into wineskins and delivered to various parts of the country on large carts for sale.

Olearius also wrote that the Caspian Sea was rich in fish resources of every kind.

The envoys had to stay near Niyazabad for more than five weeks until 22 December. During this period, Olearius got to know a little about the environment in Azerbaijan and people’s lifestyles. He described the area as a province of Shirvan, a part of it, writing that this coastal strip of Azerbaijan,

Even in December

starts from Derbend and extends to Gilan along the coast; there are 200 villages. Every turn of this country has a very pleasing appearance, the grass and trees are still green (in November and December! – Y.M.); the land is fertile and productive. The whole region is rich in rice, wheat and barley, as well as nice fruit. This country is full of trees of various kinds and also has thin forests, so birds sing merry songs here even in December.

On 22 December 1636 the Holstein envoys departed for Shemakha with their long caravan of 40 camels, 30 carts and 80 horses. As there was a shortage of pack and riding animals in the caravan, servants, service staff and soldiers had to walk. Heading south along the Caspian Sea coast, the caravan stayed over in a village called Mardov by Olearius. He noticed a kinship between the local population and the Tatars living near Astrakhan. He described the local population as living in round houses built of cane and twigs. It is interesting that as soon as Olearius stepped onto Azerbaijani territory he began learning the language. He tried to give everything that attracted his attention its Azerbaijani name.

He made notes about ‘Barmakh’ Mountain seen on the caravan’s journey from Niyazabad to Shemakha. They approached the high Besh Barmaq rock on 24 December. Writing about the medieval caravanserai there he noted that as soon as we arrived we entered the ‘open yard’ at the foot of the mountain. This was one of many such ‘yards’ and ‘shelters’ Olearius encountered in the country - a clear indication of the development of trade, including foreign trade relations.

As though we were in a paradise….

On 26 December 1636, on a sunny day, the caravan left the Besh Barmaq caravanserai, skirted Baku and made for Shemakha, which it reached on 30 December.

They were well received. The Shirvan beylerbeyi (governor) organised an official greeting for the guests. Still on the outskirts of Shemakha, Olearius realised that the country which he had referred to as ‘Iran’ was not Iran at all. He was impressed by the welcome from the beylerbeyi’s troop at the entrance to the city:

The cavalry bowed before the envoys, and greeted them with a loud ‘welcome’ in Turkish. They talk in Turkish more willingly than in Persian.

Olearius also turned his attention to the musical instruments he came across, recording the names of the unfamiliar ones. He wrote that:

we heard the war music of this strange country. Four musicians preceded us. They played a copper instrument resembling a tutek, 4 gulaj (equal to the length from fingertip to fingertip of outstretched arms) long and with a bell end. This instrument was called a garaney (the ney is a kind of end-blown flute). It was played by holding it up to the sky. There were also players of ordinary pipes and a few drummers among the musicians. They hung their oblong drums, resembling pots, over their saddles…. Some of the instruments resembled long, curved horns, there were tambourines and others among the people greeting us. The city’s population welcomed us with applause, waving and tossing up their hats, with cheering and great joy.

At the magnificent reception arranged by the Shirvan beylerbeyi, the traveller´s attention was drawn to the bread half a gulaj in size and as thin as parchment, brought on large, deep wooden plates, full to the brim. The local people called this bread yukha and a waiter was addressed as sufrechi. Olearius wrote that the dinner was conducted with absolute cleanliness and tidiness...

Today we enjoyed such luxury - as though we were in a paradise of this world.

The Holstein envoys stayed in Shemakha for three months. The German writer studied the city thoroughly, collecting a wealth of material about the people and their land. Indeed, the most interesting and valuable facts in his travelogue illustrated his stay in Shemakha.

Winter over, the caravan left the city on 27 March 1637. Walking down the Shemakha Mountains, Olearius described the inimitable view which opened up before his eyes: fertile plains, deep green slopes, peaks reaching to the skies through snowy-white clouds. In the lowlands the travellers were hosted in their winter quarters by herdsmen who met them kindly and allocated a few ‘rooms’ for their foreign guests.

Ardebil provides

On 31 March, the party reached the banks of the River Kur at Javad village. Observations noted that the Kura and Araz Rivers, flowing quietly, were 140 paces wide and deep. There was information about the Mugan region. We learn that a lot of liquorice was grown, sometimes very thickly, in the meadows on the banks of the Kur. The juice, Olearius wrote, was sweeter and more pleasing than the German variety.

On 2 April the visitors crossed the Kur by the ‘raft’ bridge there and were met by one of the Ardebil khan’s innkeepers. 40 camels and about 300 horses were waiting for the foreign envoys. Provisions had also been prepared for their onward journey: 10 sheep per day, 30 batman (1 batman = 5 kgs) of wine, a lot of rice, butter, eggs, almonds, raisins, apples etc.

From Mugan to Ardebil the travellers passed beautiful orchards, witnessed the construction of a big caravanserai for the East Indian company which trades with Shemakha and crossed the six-arched, 80-pace long, graceful stone bridge over the Garasu River; they reached Ardebil on 10 April 1637.

Olearius wrote interestingly about Ardebil, noting that the name of this ancient city was Turkic and it was situated in Azerbaijan province. Also in the province, he wrote, were Tabriz, Nakhichevan, Marand, Urmiya, Khoy and Salmas. He explained the city’s fame as the burial place of the Safavids; agreed with the belief that the British had a residence here for a while during their attack on Iran; and finally, he noted that the city was a trade centre of great importance to the local population and foreigners. His remark that the people of Ardebil usually speak in a Turkic language (Azerbaijani – Y.M.) is also valuable historical information.

The Holstein embassy stayed in the city for two months, leaving on 12 June. Ardebil’s architectural monuments, rich artistic and commercial life and hospitality made a deep impression and were written into a fascinating memoir.

The Safavid ruler, Shah Safi, received the envoys in Isfahan on 16 August and Duke Frederick’s gifts were presented to him. Olearius’ account of the reception indicates that Azerbaijani was spoken in the palace, even at official events, as far back as the 17th century. On 16 August 1637, after a one and a half hour feast given in the envoys’ honour, the Great Marshal intoned a blessing of the meal in Azerbaijani:

Toasting the meal,

The Shah’s state,

The strength of the Gazis (fighters for the faith – Y.M.)

Glorify Allah

The Holstein envoys were by no means the only Europeans at the home of the Safavid court:

After the open presentation, various foreigners living in Isfahan: Englishmen, Portuguese, Italians and Frenchmen began to visit us.

The Safavid state

Olearius gave a lengthy description of the Safavid state in the Isfahan section of his journal. He divided the state into five main provinces; three of the five cover Azerbaijani territory: Shirvan, Aran and Azerbaijan, and each province was described in turn. The return journey saw the envoys reach Astara at the beginning of February 1638. Here they saw grapevines as thick as the human body, thus confirming the ancient account given by the Greek geographer Strabo. He also wrote:

The inhabitants of Astara always keep their arms in readiness.

Cossack robbers operating in the lower reaches of the Volqa also attacked the coastal regions of Azerbaijan, including Astara, for plunder, taking everything came to their hands.

On 7 February in Lenkeran, the traveller investigated the origin of the place name, noting that langar was a place where an anchor was dropped - a harbour. He recalled here the death and burial in 1603 of Stefan Kakash, Emperor Rudolf’s ambassador.

The caravan arrived at Gizilaghaj on 11 February. Olearius wrote that there was an island here, well offshore. The colour of its earth earned it the local name Yellow Island. It was long recorded on maps as Sarah Island (in Azerbaijani sari = yellow – ed.) He also wrote that the name of Gizilaghaj was a combination of two words gizil = gold/red and aghaj = tree. He was struck by the meadow here, whose limits were not seen with the naked eye.

Back in Mugan on 12 February, the envoys stayed again in one of the ‘hamlets’ built by herdsmen. Further notes were added to the diary: in a region more than 60 miles long and 20 miles wide, there lived very many tribes and generations; he named a number of them. The population of Mugan was engaged in livestock farming and there were winter and summer lives:

In summer they go to the mountains, where there are the best pastures and picturesque uplands. In winter they set up camps in a flat desert.

Hosted all along the way, the caravan returned to Shemakha on 20 February 1638, staying there until 30 March and the arrival of spring. Passing Besh Barmaq Mountain on 2 April, the travellers then saw oil springs near the sea:

They are pits, up to 30 different kinds, located almost a rifle shot apart. Oil spurts strongly from them... The three main springs here go down to a depth of 2 sazhens (1 sazhen = 2.34 metres)... The eruption of the oil from these springs was heard from above, as if they were boiling; their smell is much stronger. By the way, compared with the smell of the brown oil, kerosene oil is more pleasant. It is possible to extract both brown oil and kerosene oil from here, but there is more of the first than the second.

Circassian and Russian merchants, who were returning from their trade in Shemakha, joined the Holstein envoys near Niyazabad. They spent the night in a nearby village:

We found many excellent books in manuscript in the home of the confessor where we were hosted.

Crowded caravan

The envoys reached the ancient city of Derbend on 7 April and stayed there for just five days. However, Olearius got down to a thorough study of the city and its historical monuments.

He even drew a map to give a better impression of the city; he then described it sector by sector and recorded some of the legends of the Oghuz people

As the visitors departed the Safavid state there were 52 rifles, 38 pistols, 6 guns accompanying the caravan’s complement of 300 cooks, doctors, diplomats and others. They were returning with a rare collection of silk fabrics, a variety of jewellery in gold and precious stones, carpets, spices, morocco and other goods from Azerbaijan to far Holstein. Azerbaijanis were with them, on their way to trade in distant lands; Russians returning from their own trading missions and merchants of various nations had also joined the enormous trade caravan sailing to Astrakhan.

By 2 January 1639 they were back in Moscow. The Safavid diplomat Imamgulu sultan, travelling to European countries, followed them there. On 5 February he was welcomed by the Tsar’s retinue at entrance to Moscow,

The Russians delivered him to the city in great luxury; so as not to detain us, the tsar received him within three days.

On 7 March, Imamqulu sultan left Moscow and went along the Tver-Novgorod-Narva-Reval route to the Baltic Sea coast, rejoining the caravan on 11 July. He and the Holstein envoys finally completed their epic journey, arriving at Duke Frederick’s residence in Gottorp on 1 August 1639….

Literature

1. Y. Mahmudov. Journey to the Land of Fires. Baku, 1980

2. Kakash and Tectander. Journey to Persia through Muscovy, 1602-1603. Translated from German. M., 1896

3. Adam Olearius. Description of a Journey to Muscovy and Through Muscovy to Persia and Back. Saint-Petersburg, 1906