Pages 82-87

Pages 82-87By Shamistan Nazirli

Words of the guide

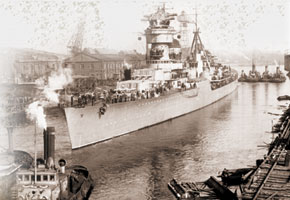

The first time I heard his name was in the museum in Sevastopol city, in 1976. The girl tour guide was standing before a picture of a giant cruiser, giving information about heroes of the war of 1853-1856. She told us:

Russia’s growing strength in the Balkans in March 1854 began to worry Britain and France. Their aim was to grab the Black Sea straits and close Russia’s trade routes. Thus both countries joined in war and moved their forces to Crimea. Sevastopol was besieged and a heroic defensive operation began. Despite the courageous struggle by admirals Istomin, Nakhimov and Aslanbeyov (she pronounced it Aslambekov – S.N.) and the Russian soldiers, the British and French forces seized the city. The impotence and decadence of serf Russia cost the country dear. Vice-Admiral Aslanbeyov, who you see in this picture, headed the construction of a railway in Sevastopol when he was a chief of the third naval squadron in 1871.

Seeking sources

The guide broke off her speech and suggested going to the next hall. Some of the visitors moved forward, looking at the Admiral’s portrait and continued on their way. I stood in front of the picture for a good while… I was seeking something in his face and eyes of a Caucasian man, specifically an Azerbaijani man. I have to admit that I instinctively felt he was a son of our nation and was in little doubt. His stately bearing and the curled moustache characteristic of Caucasian men indicated that he was of bey’s stock. I read the brief information at the bottom of the frame: Vice-Admiral A.B.Aslambekov. 1820-1900 (these dates discussed later – ed.)

As we passed to a more spacious hall everybody dispersed to look at different exhibits. Someone was pestering the guide with questions. I waited for a chance to ask one. The girl tried to end the questions, calling:

Dear visitors, come closer, don’t touch the exhibits; that is not allowed. Please, save your questions till the end…

When we were asked to move to the third and final hall I could not restrain myself and approached her.

Miss, can you clear something up for me?

This slender creature, as delicate as a swan, answered wearily:

Of course, but please be brief.

I would like to know Vice-Admiral Aslanbeyov’s nationality, nothing else…

I don’t know, - she looked at me in surprise – Wasn’t he Russian? Where do you come from?

I come from Baku. I believe he wasn’t Russian.

If you are interested in that, come to the room later. We will check it then. His documents must be there…

The main archive was closed that day. I made an appointment to meet Yelena the following day. She also suggested:

If you have time, visit the Sevastopol City Panorama today. There must be some information about Admiral Aslanbeyov there.

I was not received badly at the Panorama-Museum. However, when they realised the purpose of my visit they were not very happy. They said that the Admiral could not have been Azerbaijani. In those times our compatriots had not yet been accepted into the Army or the Fleet.

What do you mean, they weren’t accepted? I objected, they were accepted. Azerbaijani cavalry regiments, each with five hundred fighters, and a separate Karabakh cavalry regiment had fought in the war of 1853-56. Specifically, Russian military historians wrote that the Azerbaijani cavalrymen particularly distinguished themselves in the victories obtained on Russia’s Caucasian front. These victories eased the situation slightly during the battles waged for Crimea. More than three hundred and fifty Azerbaijani officers and soldiers were decorated during this war. Most of the fighters were the sons of beys, khans or nobles.

The Caucasus newspaper published many articles about them in its editions of 1849, 1852, 1855 and 1858. A list of one group of Azerbaijani fighters and officers serving in the regular army in Petersburg was published in the newspaper. In issues №48 (1855) and №83 (1858) of the newspaper it was stated that,

…the Azerbaijani lieutenant Ali Shaban oglu was dispatching from Warsaw to Petersburg, Colonel Ziya khan Mirza Nabi oglu lives in Petersburg, the cornet Idris bey Agalarov serves in the detached Muslim regiment in Warsaw.

Caucasus also printed articles about General Ismayil bey Qutqashinli, Lieutenant General Jafargulu aga Bakikhanov and his military colleagues.

Unfortunately, I could not find any articles about Admiral Aslanbeyov. But literature provided by museum staff revealed that he was badly wounded during heavy fighting in Sevastopol.

I went to the central library and ordered all the books about the admiral. I came across the following information in Yuri Davidov’s book Nakhimov:

The consultation determined that Nakhimov’s condition was hopeless. Doctors didn’t believe he would survive. His struggle for life lasted forty hours, then his death agony began. These moments were described clearly in the diary of an eye-witness, Lieutenant

Commander Aslanbeyov:

On 30 June, around 11 am, his breathing became heavy. Silence dominated the room, doctors ceased their discussion and everybody approached the bed. Sokolov said, loudly and very clearly: “Death is approaching…”

After a certain time, Sokolov answered Voyevodsky’s question: “He is dead”. Everyone looked at their watches, it was ten past eleven.

Davidov explained that there was no fantasy in this record by Lieutenant Commander Aslanbeyov, who was Admiral Nakhimov’s closest colleague. All Russian researchers, including academician Y.V. Tarle, a famous military surgeon and doctor, war participant N.Pirogov and others writing about Admiral Nakhimov have relied on Aslanbeyov’s account.

Later Aslanbeyov, himself author of Biography of Nakhimov, wrote:

Nakhimov, on hearing of the death of Admiral Kornilov went to pay his last respects. When I entered the room Nakhimov was crying and kissing his friend Kornilov, already dead.

I was excited, and could hardly wait for tomorrow to come.

We went to the yard via a long corridor. Then down a winding staircase and through a door on which there was an inscription The Guard Room, Pre-Revolution. Yelena gave all the details to a grey-haired woman. Her expression was one of puzzlement. She played with the pencil in her hands and glanced at me quizzically and ironically. The woman mumbled something and fidgeted. Yelena, who felt that the woman was in a bad mood, spoke as though she was asking something for herself:

Please, do this for me and for this man who has come from far away. It seems very important…

The director of the archive said nothing to either Yelena or me, but stood up and turned to the left and disappeared between the shelves.

Approximately ten or fifteen minutes later she returned with an old, grey folder, sat down as if we were not there and began to turn over the pages. The noise of pages turning from time to time increased my excitement in this semi-basement where deep silence reigned.

After a while she said:

Let’s see. I personally doubt that such an eminent admiral could be a Muslim…

I could not bear it any longer. Honestly, I was afraid that she would look through the folder herself and then put it back. I stood up, took my passport and identity card from my pocket and put them on the table.

Here you are. I trust these two documents to you. And in return give me the folder, I will look myself.

I felt that Yelena was upset by my impatience. She said, uneasily and in a low voice:

That will never do…

The director did not resist and gave me the folder, saying tetchily:

Well, take it.

A question of identity

I looked over the Admiral’s personal history and couldn’t believe my eyes. My breathing was heavy and my hands were shaking. I could not contain myself any longer and wanted to share my joy with them:

Let me read you the Admiral’s name and surname.

The director did not respond. But Yelena, who understood my victory and joy said excitedly:

Please, read it.

I read:

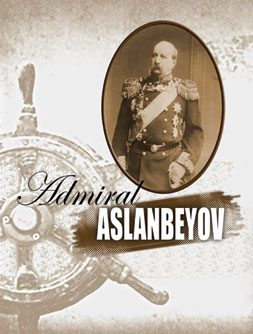

‘Aslanbeyov Ibrahim bey Allahverdi bey oglu’. This is the original. But later this surname and name were crossed out with black ink and a correction was made: ‘Aslambegov Avramiy Bogdanovich, was born in 1822, in Baku. Comes from noble family. His religion is Islam.’ The last sentence was also crossed out and instead of it was written ‘an Orthodox’.

If it is allowed, could I make notes from the Admiral’s personal history?

Yelena answered joyfully:

Of course, you can. Please, sit down and make your notes. Let me leave you.

After Yelena had accepted my gratitude with pleasure and left us the director stated in strict tones:

Comrade, you can make notes, but it is forbidden to make a photocopy of a personal history kept in this unique archive.

Thank you, I said. These notes should be sufficient.

I had long known that there was no such prohibition. But I decided it would be out of place to argue here for lack of time. The main thing was I had made a unique discovery about my compatriot, the first Azerbaijani vice-admiral. This pleasure was enough.

Voices from the sources

The first admiral in the history of the Azerbaijan navy was the son of Dargahgulu bey, the first Mirza Muhammad khan. Unfortunately, it has not been possible to find his photograph or retrace his life path completely. However, the history of the navy contains some information about Mirza Muhammad’s career. He inherited the Baku khanate when he was twenty years old and brought order to the economic situation in the khanate which had fallen into decay after his father. He had also given priority to developing navigation on the Caspian Sea. It was he who had initiated improvements to navigation in Baku’s port. He had even travelled to Europe to study its experience in navigation. The following episode in the documentary work Baku and Baku’s Citizens by our eminent writer Gilman Ilkin provides valuable information.

One day Mirza Muhammad khan called his son Malik Muhammad to him:

Listen, Malik Muhammad, I am going to tell you something. We are sitting on the sea coast but we don’t have our own ships. Fishing boats are not enough. We need vessels with which to defend ourselves from enemy attack.

Malik Muhammad did not understand any of his father’s words and looked at him blankly.

For this purpose I need to travel to Europe - said Mirza Muhammad with a deep sigh. The best vessels are made there.

But who will stay here? – Malik Muhammad asked.

Who? You!

Malik Muhammad had occasionally helped his father, but he did not expect such responsibility.

The traveller Lerkh who was in Baku at that time wrote that the Baku khan, Admiral Mirza Muhammad, often went to shipyards to organise boat building.

There is another source from the early nineteenth century. Azerbaijan navy forces in the Caspian Sea comprehensively routed Russian forces which entered Azerbaijan attempting annexation from 1804-1806. The Iranian historian Nasir Najimi wrote that Huseyngulu khan, Abbas Mirza’s courageous military leader and commander (in truth the Governor-General) of Baku trained cannons on the Russian ships and, displaying amazing alacrity and selflessness, sank several enemy ships with cannon fire.

The graduation of seventeen-year-old Ibrahim bey Aslanbeyov from the Navy Corps in Petersburg was surely in accord with the wishes of the first admiral, Mirza Muhammad. There was an Allahverdi in the Bakikhanovs’ family tree. Perhaps Ibrahim bey Allahverdi bey oglu Aslanbeyov was a son of that Allahverdi bey?... Unfortunately, after one hundred and seventy three years it is not possible to confirm this. But we must remember that a thirteen year old son of a low-status family would not have had the opportunity to study in Russia. So our first vice-admiral, Ibrahim bey Aslanbeyov, surely belonged to a family of Baku khans.

The detail in his personal history about being from a noble family offers further support.

Usually, the encyclopaedia contains information about the birth place and nationality of any eminent person included. But there was no such information about Admiral Aslanbeyov either in the multi-volume Military Encyclopaedia of the famous publisher I.D.Soitin, issued in 1911, or in naval encyclopaedias published in the Soviet era. It seems that Russian naval researchers benefitted from the appropriation of this eminent commander. And why not? Indeed, Vice-Admiral Aslanbeyov is also known as a famous scientist in naval history!

The admiral’s life story

In some sources, especially in those from Soviet times, Aslanbeyov’s date of birth was given as 1820. In our opinion this is a mistake. Actually, sources published before the 1917 revolution noted that Admiral Ibrahim bey Allahverdi bey oglu Aslanbeyov was born on 10 September 1822 in Baku. Ibrahim bey, who studied at the naval school in Petersburg for three years, graduated in 1837 (with honours). Midshipman Aslanbeyov sailed on the naval frigates Alexander Nevsky and Prozergin on the Baltic Sea and trained for two years on the high-speed naval ship Tsar Peter I near Dagerod.

After graduating from the officer class of the naval school in 1842, Ibrahimbey sailed on military control ships of the Black Sea Navy and participated in battles off the eastern coast of the Black Sea.

In 1854 Lieutenant Aslanbeyov, commanding the military ship Elbrus, went to sea four times in order to rout enemy merchant ships (on 30 June, 7 July, 3 and 6 August) and in August he commanded the assault crew of a landing vessel. For this service he was promoted to lieutenant commander. He served in the Sevastopol garrison from 13 September of that year until the end of the war, repulsing the final attack on 27 August, during which he was wounded. Following the eastern war he commanded the 36th naval crew in Port Nikolayev.

From 1860-1861 Aslanbeyov sailed the Mediterranean as commander of the propeller corvette Sokol (Falcon) and taking it to Kronstadt. In 1863 he returned to Nikolayev with the same corvette and after two years was assigned commander of the ship Retvizan. For a certain period the vice-admiral was chief of staff in Butakov’s armoured squadron.

From 1869-1872 Aslanbeyov served many times as chairman of various committees established to study various issues of national importance. Ibrahim bey, who was dispatched to Estonia, was a member of the committee established to set up naval schools and build merchant ships.

On 1 January 1878, when Ibrahim bey Aslanbeyov was made up to rear admiral, he became chief of the eighth naval squadron.

His biography as admiral and a naval historian is a very full one. If we compare it with the careers of other servicemen, Aslanbeyov’s services were only equalled by those of General Aliaga Shikhlinsky to artillery. The only difference being that Shikhlinsky’s scientific and military career was more closely associated with Azerbaijan. Although Aslanbeyov’s scientific research was widely used in Russia, it was little known in his homeland.

In 1872 Peter I’s bicentenary was celebrated with great ceremony in Russia. Our compatriot Aslanbeyov was entrusted with participation in the All-Russia exhibition of engineering and with escorting the Tsar’s detachment of small rowing ships to Moscow. From 1879-1882 Ibrahim bey led an around-the-world voyage. He also headed the military staff of high-speed armoured military ships and steam vessels (Minin, Knyaz, Pojarskiy, Duke of Edinburgh, Asia and Africa) in the Pacific Ocean. He initiated the navy’s use of cruisers and a high speed flying squadron on the oceans. At the behest of Admiral A.A.Popov he compiled a list of requirements and shortcomings to be considered for the latter project.

It is clear from conclusions and memoirs recorded in his personal history, particularly in prerevolutionary literature on the Navy, that Aslanbeyov earned great respect from his staff. A rear admiral, whose name is unclear in a document faded over the years, wrote that Aslanbeyov, who valued highly the name of Russia, was also well known in other countries. He had the skill of stiffening the spirit of a ship’s crew. Initiative, even from the lower ranks, was valued. He was distinguished for his open-heartedness and resolution. Many jokes about his voyages, as well as the comic eastern stories he told are still famous.

In 1884, Rear Admiral Ibrahim bey Aslanbeyov was assigned to be junior flag officer of the Baltic command. Three years later, on 22 September 1887 he attained the rank of vice-admiral for outstanding service to the Navy and was then assigned flag officer of the Baltic Fleet; he died on 7 December 1900 in St. Petersburg.

He was a friend of our compatriot, the orientalist Mirza Kazim bey and the great Russian writer Lev Tolstoy sought him out and asked him to relate the scene of Admiral Nakhimov’s death. Tolstoy benefitted from the admiral’s memories while writing the famous Sevastopol Stories. Admiral Ibrahim bey Aslanbeyov, who spent more than fifty years of his life in exemplary service to the Navy, was decorated with high honours in Russia and other countries. The services of our compatriot were recognised by such orders as Takova, Serbia (1879); Saint Vladimir (1854); Saint Stanislaw, First Class (1881); Saint Anna, First Class (1883); White Eagle, Russia (1888), Sunrise, Japan (1882); Kalakiya Second Class, Hawaii (1882).

Aslanbeyov, who participated in the coronation of Tsar Alexander III in 1881, was presented with a sword and allocated a money award amounting to an annual salary.

On the map

Even during his lifetime, in 1882, an island in Sakhalin and a gulf in the Sea of Okhotsk were named after him.

The brief autobiography of our compatriot given on pages 28 and 253 of Boris Maslennikov’s book The Sea Chart Narrates, published in 1986, has great significance. The writer presents, for the first time, facts assembled from substantial sources:

The Aslanbeyov Peninsula, the Sea of Okhotsk, Sakhalin Island, the crew of a clipper are depicted in 1882. This was named after the commander of the Pacific Ocean, Rear Admiral Ibrahim bey Allahverdi bey oglu Aslanbeyov. Surnames on the chart have spelling errors.

The Aslanbeyov gulf, the Sea of Okhotsk, Sakhalin Island, was discovered in 1882 and added to the chart by the crew of the clipper Plaston. They were named after Aslanbeyov at the same time.

Ibrahim bey Allhaverdi bey oglu Aslanbeyov (1822-1900). He graduated from the Naval School, sailed on the Baltic Sea from 1837-1842. Aslanbeyov served on the ships Selafail, Warsaw, on the brig Femistokol and other vessels of the Black Sea Navy. He was commander of the ship Retvizan from 1865-1868 and commander of the Pacific Ocean squadron from 1879-1882. In 1887 he received the rank of vice-admiral.

A strange and pleasant coincidence

In September 1993 I was on a business trip in the Qakh region when I met a young man called Eldar Haji oglu Mammadov in Marsan village. I enquired about his occupation.

I am an engineer, he said. I have been engaged in producing oil for 14 years on Sakhalin. I came here for a holiday.

Have you come across an island called Admiral Aslanbeyov by any chance?

I live and work on that island, he answered.

What a pleasant coincidence! A compatriot lives and works on the island named after the Azerbaijani admiral.

Do you think Admiral Aslanbeyov was Azerbaijani? Do you know that for sure?

Yes, I said, he was our nation’s first vice-admiral.

We have often had arguments about it with inhabitants of the island and people from other nations. I and our compatriots, declare from the surname that the Admiral was a son of our nation, but we don’t have any evidence to prove it. We don’t even know when he lived and died... I have asked eminent intellectuals of our region a few times about this when I have been here on holiday. But everyone has answered that we don’t have such an admiral.

I gladly told him:

We have, Eldar. On your way to Sakhalin, came to Baku. We can meet there and I will give you pictures of the admiral and his autobiography. Then you will have evidence of his origin.

Eldar rejoiced more than me:

Thank you, he said, I will devote a corner to Admiral Aslanbeyov in the settlement cinema.

The Admiral was a scientist

Russian researchers writing about Admiral Ibrahim bey Aslanbeyov proudly noted that:

he was more famous as Admiral Nakhimov’s biographer.

It is no coincidence that Ibrahim bey’s essay Biography of Nakhimov has been published several times.

The Admiral’s scientific and social and political essays are worth examining separately. Most researchers investigating the history of the 19th century navy use them as a source, even today. It was no mere chance that in 1889 a book called The Half-Century Anniversary of Vice-Admiral Aslanbeyov was published in Saint-Petersburg. A book by V. Fredrick, African Cruiser Sailing under the Flag of Rear Admiral Aslanbeyov was also issued in Saint-Petersburg, in 1880. The admiral’s diary was used extensively in Sevastopol, a book of historical sketches, by G.I Syomin (1955).

Prince Admiral V.I.Baryatinsky, in his memoirs of our compatriot, noted that his anecdotes about the East and the Caucasus were so lively that listeners laughed themselves into fits. These stories are still told by sailors.

From the 1860s onwards, a number of scientific, social and political articles by Admiral Ibrahim bey Aslanbeyov were printed in the magazine Morskoy Sbornik (Marine Collection) magazine. Researchers still benefit from such articles as Voyage of the Sokol (Falcon) Three-Masted Naval Ship from the Mediterranean Sea to Kronstadt (1861), Admiral Nakhimov (biographical essay, 1868), Admiral A.S. Greyg (1873), Admiral A.I.Panfilov(1874), Speech on the 50 year Anniversary of the Marine Academy (1877), Information on the Voyages of Rear Admiral Aslanbeyov (1881) and others.

About the author: Shamistan Nazirli is a lieutenant-colonel, senior officer and senior staff historian in military history at the Military Scientific Centre. He has written books and articles on the military history of Azerbaijan.