Jeffrey Werbock made his first appearance on Azerbaijani television some twenty-four years ago when this was still part of the Soviet Union. He journeyed from his USA homeland and first set foot on Azerbaijan soil shortly afterwards. Since then has been a regular visitor and an even more regular performer in the West of the traditional instruments tar, kamancha and oud and the mugham music they play. He is an enthusiastic campaigner for the recognition by name of the beautiful carpets produced in many regions of the country.

Jeffrey Werbock made his first appearance on Azerbaijani television some twenty-four years ago when this was still part of the Soviet Union. He journeyed from his USA homeland and first set foot on Azerbaijan soil shortly afterwards. Since then has been a regular visitor and an even more regular performer in the West of the traditional instruments tar, kamancha and oud and the mugham music they play. He is an enthusiastic campaigner for the recognition by name of the beautiful carpets produced in many regions of the country.On 3 November last year, Azerbaijan paid unique tribute to this man who has helped so much to promote its music to the wider world. The cultural great and the good assembled to help Jeffrey celebrate his 60th year. The event was, of course, televised, but the main pleasure was to be had in Baku’s Mugham Centre listening to the tributes spoken, played and sung, and reflecting on the warmth of feeling between an American and a culture he first glimpsed in California. We asked him to explain his creative journey and the attraction of Azerbaijan. Here is the first of his three-part explanation.

The USSR

The first time I set foot in Azerbaijan was in June of 1989, when it was still a Soviet Socialist Republic. At the time, the country was under martial law. There had been a few instances of ethnic strife on account of a brewing conflict with Azerbaijani citizens of Armenian descent, as well as a first wave of refugees and displaced persons, mostly Azerbaijanis, who had fled the neighboring Soviet Socialist Republic of Armenia.

According to numerous sources, the city now called Yerevan (formerly Irevan) and the region known as Zangezur were predominantly Azerbaijani, and first one then the other had been incorporated into Armenia, suddenly putting many thousands of Azerbaijani families inside the rival country. At the same time there were many Armenians living in Azerbaijan, some with strong nationalistic ambitions. It made for plenty of ethnic tension which soon after my first visit boiled over into open armed conflict, in which an entire swath of western Azerbaijan, which includes the district called Mountainous (Nagorno) Karabakh, was ethnically cleansed of its non-Armenian population.

Parallel to the growing ethnic tensions was a powerful undercurrent driven by the tantalizing prospect of freedom and independence, after so many centuries of dominance by foreign powers. This was in the late stages of Gorbachev’s leadership and the spirit of glasnost and perestroika - openness and reconstruction - permeated the atmosphere of Soviet Azerbaijan.

Awaiting me at the old Bina airport were two agents from the local Friendship Society, a now defunct Soviet institution whose mission was to greet and attend to foreign visitors invited by the government. They were affable men, fluent in English, and they greeted me with warm hospitality and a surprisingly easy-going demeanor. Thus began a 12 day tour of various cultural and personal experiences that remain in my memory as the beginning of a warm and enduring relationship with Azerbaijan and its people.

Mugham paves the way…

The adventure began with a letter I sent to them late in 1988, informing them that since 1972, I had been a passionate devotee of their ancient traditional art music known as mugham. Having studied the kamancha and tar - two native Azerbaijani stringed instruments - by the time I arrived in Azerbaijan I was already making my way along the path of learning this unique style of ancient eastern music. Still playing at an amateur level but driven by a strong sense of purpose, I went to Azerbaijan mainly to find another teacher, as my first teacher, an elderly kamancha player originally from Daghestan, had, at the age of 77 passed away, leaving me yearning for more.

I had met my first teacher of mugham and kamancha in Los Angeles, California, owing to a serendipitous meeting with some friends who knew of my musical interests and who urged me to search and find this unusual old man, a musician of the Caucasus. His version of mugham was very simple yet incredibly intense. The very sound of his instrument, his unique touch on the strings, bowing with grace and power, and his whole approach to mugham riveted my attention and transformed my state of mind into something extraordinary. His music had a mesmeric power; it was an enchantment in sound, and I was entranced.

…to real, live Azerbaijanis…

After about 15 years of trying my best to absorb the basic musical sensibilities and learn the elusive melodies of mugham and related folk tunes, my beloved teacher passed away. About one year later in this dark period in my life, I learned that there was going to be a concert in New York City - where I lived and worked - of professional Azerbaijani musicians and singers who were visiting the United States.

With my hopes suddenly revived, I went to the concert with an Azerbaijani friend who was originally from Ardebil in Iran; this was in 1988. Three singers performed, one woman and two men, and a top notch ensemble of musicians. Two of the musicians played native stringed instruments, one on tar and one on kamancha.

This was the first time I had heard a live performance of professional Azerbaijani instrumentalists, and I was blown away. All the previous years had been mere preparation, enabling me to appreciate what they were playing and how accomplished they were at their art. After the concert, I beseeched my Iranian Azerbaijani companion to go with me backstage and translate for me so I could tell them about my desire to learn their music.

At first they were skeptical. But then two of the musicians agreed to let me pick them up and drive them to my apartment, where I had numerous Azerbaijani musical instruments on display. Entering my living room where I kept my cultural treasures, they couldn’t help but respond to the strange American who loved their music.

It was only one afternoon, but it was all that was needed to gain their trust, and to find out the name of the person I needed to write to in order to obtain an invitation to come to Azerbaijan. It was important for me to be allowed to visit Azerbaijan as an individual, because the only other way foreigners could visit a Soviet Republic was through Intourist, an official government agency. One is forced to travel in a group which would take us to other cities that held little interest for me. My interest was strictly in Azerbaijan, and my aim was to meet musicians and experience the culture that gave birth to mugham.

…to fame in Azerbaijan…

Coincidentally, just at the time I received my invitation, the same group of musicians with one of the singers from the first tour returned for a second tour in America. This time everyone was very open and friendly with me. I volunteered to host three of the musicians in my apartment in New York City, and arranged for the lead singer, Zeynab Khanlarova, to stay in a hotel room near Times Square. One of the men who stayed at my place, a tar player named Zamiq Aliyev, took me along to their rehearsals. This evolved into including me in the program, a kind of cameo appearance on stage, singing a duet with Ms. Khanlarova and also playing the tar and kamancha.

Later, when the group returned to Azerbaijan with video footage of their concerts, the editor of a popular television program - Dalga (Wave) - specializing in the unusual, reviewed that material for possible broadcast. Seeing the part in which the American aficionado of Azerbaijani music played and sang one of their famous folk tunes, he decided to include that in a broadcast. By the time I arrived in Baku, the American who loved Azerbaijani music was the talk of the town.

Azerbaijanis are very open and cosmopolitan people who genuinely love the guest, especially outsiders, and they are even more positive toward those who show a genuine interest in their culture. Naturally, I enjoyed their hospitality and friendliness, and did my best to return the good feelings.

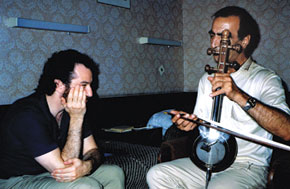

Two years later, I returned to Azerbaijan to get music lessons on the tar from Zamiq Aliyev. We only had ten days together so there was some pressure to work hard at learning one mugham. His brother worked at the television studio, he sent an interviewer and cameraman to Zamiq’s apartment and they filmed one of our lessons and did an interview. In addition, Zamiq arranged for me to perform at the Philharmonia Hall.

This was impressive because I was playing at the level of a rank amateur and he was a very advanced mugham musician. From the beginning of my relations with Azerbaijanis, the fact that I was playing their music at beginner’s level never seemed to be an obstacle to their appreciation for my love of their traditional music. The music I played was relatively simple and unpolished, but it came from my heart, and they seemed to understand that.

Independence, crisis and boom

Later that year the Soviet Union collapsed, and Azerbaijan was free at last. However, the ethnic conflict brewing in western Azerbaijan escalated into a full scale war, with all sorts of unhappy repercussions for the new republic. The government, a democratically elected leadership, was unable to handle the crisis and there was a coup. Economically, Azerbaijan suffered terribly from being cut loose from the Center and had yet to exploit its vast oil wealth.

Some years passed, and the mood there was very low. Finally, the war came to a cease fire, after the loss of considerable territory and a massive refugee crisis, and then the international oil companies came to Baku and formed a consortium. By 1997, after negotiations led by President Heydar Aliyev, a former Secretary General of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan and Politburo member in Moscow during Leonid Brezhnev’s regime, the oil consortium signed a contract with Azerbaijan, unleashing an economic boom that is still unfolding today.

That same year, I received a phone call from the consortium’s director of public relations, an Azerbaijani man named Guivami Rahimli, inviting me back to Azerbaijan to perform at the newly renovated Opera House. Renting an apartment near the Music Conservatory, I had one week of lessons and rehearsals, an unforgettable week of very little sleep, a parade of visitors, and a lot of music. There wasn’t much time to play the tourist, to say the least. And on the Friday evening, the last full day of that hectic week, was the concert.

Inviting Mr President

Friday morning, Guivami came to my apartment to inform me that Heydar Aliyev, the President of Azerbaijan, had learned of my presence in his country and invited me to meet him in his office. I was feeling a bit weary from lack of sleep, and a bit concerned about not staying at home and practicing for the concert that evening. But there was really no choice in the matter. Had I declined the invitation, my new friend Guivami would have been most uncomfortable, failing to carry out the president’s request to have us as his guests.

It was an interesting meeting, lasting nearly an hour. Although this was only my 3rd visit, my Azerbaijani language skills had improved over the years, which allowed me to speak directly to the president in his language, but not enough to dispense with a translator when he spoke to me.

The impression he created was one of extreme thoughtfulness, thorough preparation and long practice at the art of public speaking. Although I cannot speak Azerbaijani as I speak English, this time I was able to follow his thoughts, even when he used words I was unfamiliar with. I thought to myself at the time that Azerbaijan had a unique and talented personality to lead them through their various crises. Who could better negotiate with the oil companies, with Russia, stinging from their colossal losses as the rulers of the Soviet Union, and with Iran, a belligerent and possibly dangerous neighbor?

Prior to our first meeting, I had read about him and learned a few things; I had read that he had played the tar, so I asked him if he still played and I was graced with another charming smile, this time with a hint of shyness, saying Oh, that was in my youth. Near the end of our conversation, I invited him to the concert that evening and pointed out that the printed invitation I offered him was actually for two people, as if he needed an invitation, as if he needed to be informed that he could bring a guest! We all had a hearty laugh over that, and the people who were witness to this exchange still tell the story about how this crazy American invited the now iconic President Heydar Aliyev to his concert, saying he could bring anyone he liked!

Later I learned he spoke with some of the musicians at another event and praised the idea of bringing the American who loves mugham to the attention of the public. He wanted people to understand that he supported the traditions of Azerbaijan, including the music, and that traditional culture is important because it is an essential ingredient to national identity.

TRAVELLING OUTSIDE BAKU

My visits to Azerbaijan became more frequent and I began to explore the regions outside of Baku. Once outside the city, Azerbaijan shows a very different character. On my first trip in 1989, one of my hosts had taken me to Sheki in north-west Azerbaijan. We stayed at the ancient caravanserai, a stopping point on the old Silk Road, where merchants could trade and rest. The rooms and facilities were quite comfortable, having been recently renovated.

I had also been to Basqal and Lahij. The latter village is located high up in the mountains, and at the time was only accessible from spring to the fall. Famous for its handmade copper crafts, Lahij was also home to a wise old Hajji, a religious figure who is the head of a family of crafts men and women. The men work the copper and the women weave the carpets. We were guests in his house. A friend of one of the agents accompanying me was having some personal difficulties. He had recently lost his mother to cancer and had taken to drink. Opening his troubled heart to the bearded old Hajji, he begged for his help to free him from this pernicious habit.

It was a very moving scene. The troubled man was not particularly religious but he put his trust and faith in the Hajji to help him. He took vows in front of us, something I had never witnessed before other than the ritual of weddings, and this extraordinary episode became part of my first impressions of the people of Azerbaijan.

After Lahij, we went to my guide’s friend’s summer place in Basqal. He had a large house and a backyard in a forested setting. Honoring the guests, our host sacrificed a sheep, right there in his backyard. The host invited me to watch. From the viewpoint of an American middle class upbringing this was a grisly spectacle. I grabbed my camera thinking I should capture this moment. Most likely it was not going to be the last time I got to watch this traditional practice, and I thought I better try to get used to it.

Toasting friendship

The homemade vodka of Azerbaijan, distilled from various fruits such as mulberry (tut), cornelian cherry (zogal) and apricot (erik), are wonderfully aromatic and intense, about 60 per cent (120 proof), sharp and clean, and warming to the palate. After a few toasts, the warmth spreads all over and invades the thoughts in a most pleasant way. Unfortunately it isn’t available back home so it remains for me a part of Azerbaijani exotica.

Oddly, I never witnessed a drunken Azerbaijani. I have seen many a non-Azerbaijani lose their composure and self control under the influence of alcohol, but for some reason Azerbaijanis seem to keep a hold on themselves. I don’t have any explanation for this, but I can relate one episode that might shed some light upon it.

During one visit to Baku in late 2001, Guivami took me to a restaurant that was really a small compound of tiny ramshackle cabins slapped together with sheets of plywood set up on a packed dirt floor. The facilities were primitive, to say the least, and yet here we were smack in the middle of the city. The food was really delicious and was accompanied by the usual high proof vodka locally distilled from one or another aromatic fruit; I no longer recall which one.

One by one, each of the men among my friend’s circle of his friends stood up to deliver an eloquent and heartfelt toast, honoring one or another of the seated men. The toasts were spoken unhurriedly, even leisurely, and with poetic grace, laden with superlatives and gratitude for the existence and presence of the one being toasted. I couldn’t help but contrast that ritual to my experiences as a westerner where men not only do not praise each other and lavish warm sentiment upon one another, but instead insult and degrade each other in a fake macho contest of who can be cleverer in mutual put-downs. The friendship and warmth that Azerbaijani men bestow upon one another during the toast rituals is exceedingly pleasant and that too has a real impact. I suspect it may be the reason why Azerbaijani men do not get drunk on their fiery home-crafted vodka in a group.

To seek the approval of others is a real human need, and to receive it so generously and poetically is nothing less than a cultural richness, the accomplishment of a society rooted in tribal-based inter-relations. No one had any desire to show off or ‘best’ another. It was a group phenomenon, yet one that did not diminish the individuality of the participants. As a westerner deprived of such a luxury, it almost felt like medicine, a balm to soothe the hurt that comes from just being alive and having to live in a world of brutality and occasional hard luck, and a chance to feel something of real value in life. It redefined the meaning of friendship, and I have to admit to a twinge of envy that this lifestyle and ritual, so taken for granted by these men, is virtually unknown in my world. I also felt profound gratitude that this close-knit group was so open to including an outsider, and for regarding me as one of them, even if only for one evening.

Culture sustained

It was not until the year 2000 that I had the chance to see more of the Azerbaijani countryside. The purpose of this trip, which took me and seven other men to regions southwest of Baku, was a cultural expedition. We were to visit the various refugee camps in search of young talented Azerbaijanis who were capable of singing or playing mugham. The first time I heard of this phenomenon, I was incredulous. Mugham is so complex and nuanced that when adults perform it, it is nothing less than amazing. The thought of children doing it, especially the singing, a very difficult technique and employing very sophisticated poetry, seemed impossible.

So when I was asked to participate as a jurist in a competition called the Children’s Mugham Festival, I hesitated, mostly out of a sense that it was inappropriate for an outsider to pass judgment on who performs best. But I thought I could combine this interesting situation with my long standing desire to visit the refugee camps, to see for myself what life was like for these many hundreds of thousands of unfortunate victims of civil and ethnic unrest.

The children were a special treat. I could not detect any anger or resentment in any of them. Apparently they accepted their fate with a forbearance that was, from my perspective, nothing less than heroic. I would like to attribute this positivity to the close-knit family ties and very rich culture of Azerbaijan. In any case, the light that shone from their eyes was remarkable, and the emotionally powerful songs they sang were both delightful and astonishing. Not every one of them sang perfectly on key, but they all sang and played with gusto. A few of the really young ones appeared eager to please the adults, who freely poured their indulging approval on the children, with beatific smiles and bright shining eyes. It was really a sight and sound to behold. The landscape in and around these camps was bleak. The roads were in poor condition and it was difficult to get around. Some of the refugee camps consisted of mud brick homes; some were animal transport railway cars made of corrugated steel panels. Ovens in the summer, refrigerators in winter, life in these camps must have been unspeakably harsh, especially in comparison to the relatively good lives most enjoyed before the war broke out.

Even under these tragic and harsh life circumstances, the Azerbaijani population did their best to preserve their traditions and their dignity. Even here, the hospitality was offered freely. I returned to these regions in 2008, again with a film crew, to video our search for the youngsters we had recorded in 2000, to see if they still followed the path of mugham, and to meet some members of the new crop of young mugham singers and musicians. We are on our way to completing this documentary film, hopefully this year (2012).

Drizzled with mountain honey…

My first trip to Ganja in west Azerbaijan was in 2003. On the way I visited Mingechevir, a small city on the banks of the river Kur, where my hosts, a husband and wife, both medical doctors with a practice and apartment in Baku, and dacha (summer home), maintained a small residence. Originally from Mingechevir, their college-age son had been a guest in my house for some years while attending Temple University, not far from where I lived with my family in Cherry Hill, New Jersey.

They treated me very nicely and took me to see all the sites of interest, and we also attended the weddings of the children of their friends. We drove to Ganja and beyond, to a place called Hajjikend, high up above the plains, to a place that was basically an outdoor restaurant, situated on the high point with a spectacular view of the surrounding territory. The clean high mountain air, the inevitable local spirits, the good food, the fine company and the wonderfully spirited music of some local musicians, all converged to make for a really rarified state of mind.

On the way home, I noticed that the mountainous winding road was lined on both sides with handmade clay baking ovens and racks holding jars of local honey and the freshly baked bread, tandoor chorek. I thought we should stop and get some supplies for the next morning. Topped with a local dairy product called qaymaq, a kind of clotted cream, the fresh baked bread drizzled with mountain honey, and hot fragrant tea, is one of the treats of Azerbaijan that everyone who comes to visit should try at least once.