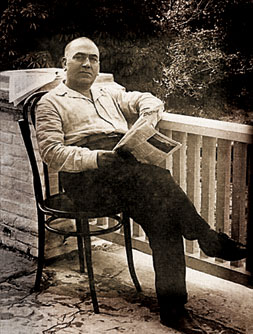

People’s Artist Azim Azimzadeh (1880-1943) left us with a priceless artistic inheritance, but how is it that the works of an artist without professional education continue to fascinate more than a century later? We hope to clarify his unique achievements, shedding light on certain moments in his life and art...

People’s Artist Azim Azimzadeh (1880-1943) left us with a priceless artistic inheritance, but how is it that the works of an artist without professional education continue to fascinate more than a century later? We hope to clarify his unique achievements, shedding light on certain moments in his life and art... Of course there is a context for his work and we should explain that he was called the Mirza Alakbar Sabir of Azerbaijani fine art. He was certainly Sabir’s contemporary, but he also shared the writer’s critical views on the discrepancies in people’s lives, the pains, problems and distortions they faced. Like Sabir he used humour on the pages of the Molla Nasreddin magazine, but his vision was cast in colour and image as he tried to rouse those who made up the majority in society by exposing the negatives he saw to his sharp wit.

The legacy of a beaten schoolboy

Azim Azimzadeh was a master of the satirical drawing and he made a deep impression on the development of Azerbaijani graphics, enriching the tradition with a huge variety of images and styles. His paintings and graphics have a distinct aesthetic, embracing both the traditions of Tabriz miniatures and the principles of contemporary realism. Through the Soviet era, Azimzadeh was an educator in modern style and fostered new artists. Notable pioneers in their own right Alekber Rzaguliyev, Sattar Bahlulzadeh, Mikayil Abdullayev and Maral Rahmanzadeh were among the many students of the great man.

The artistic heritage that was the outcome of his 40 years’ work includes more than 3,000 satirical drawings, murals, caricatures, illustrations, posters, stage sets and costume designs; an invaluable contribution to the country’s art treasury.

Azim Azimzadeh was born in 1880 in Novkhani village on the Absheron peninsula into the family of Karbalayi Aslan. Little Azim studied at the mullah’s school but was beaten soundly for drawing during his Qur’an lessons, which was considered to be the devil’s work. He finally ran away and started at the Russian-Tatar school but his education did not last long and, under pressure from his father, he went out to work. He found a job in the office of a mill owned by Aghabala Guliyev and occasionally encountered the Russian artist Durov who was decorating the Baku entrepreneur’s newly-built home with paintings; he even assisted Durov in his spare time. This chance meeting strengthened his desire to study fine art and he approached one of the city’s wealthy elite for support, only to be told:

Hey boy, be smart, find yourself a profession. We need engineers not painters!

From Mullah to Molla

After that Azim gave up his quest for training and began freelancing as an artist, sending one of his drawings to the Molla Nasreddin magazine recently launched in Tiflis (1906) by the writer and democrat Jalil Mammadguluzadeh. The drawing, Irshad’s Client, was published, boosting his confidence, and thus began his cooperation with Molla Nasreddin as well as with other magazines published in Baku such as Mezeli (Funny), Baraban (Drum), Kelniyyet, Babayi-Amir, and Bij (Trickster). His contributions were mainly caricatures and satirical pictures commenting on everyday events. In the 1920s and1930s he worked in various spheres of fine art: newspaper and magazine graphics, book illustrations and stage design. His talent was recognised by his appointment in 1920 as head of the art department of the Republic’s Education Commissariat, and in 1922 as chief artist of the newspaper Communist, the most prestigious in the country and of Molla Nasreddin, then published in Baku. In 1927 there was a great celebration to mark the 20th anniversary of his creative activity and people made very clear their love and respect for him. In the same year he was given the honorary title People’s Artist, the first artist to be so awarded.

Along with the satirical drawings in magazines, Azimzade’s illustrations for the 1915 and 1922 anthologies of the Azerbaijani poet Mirza Alakbar Sabir (pen name Hophopname – Hoopoe’s Tale) were especially important works. The artist, who drew 24 coloured pictures for the first edition, enriched Hophopname with 33 more illustrations. He felt deeply the irony laced with sorrow peculiar to the poems and the poet’s tragicomic spirit, and created memorable works visualising the poems’ intent and making people think. The titles indicate the themes: Beggar, I Don’t Care About The People, Farmer, Worker, I Don’t Let My Child Study, Leave Me Alone!, I’m Selling, I’m Scared ... Since its publication the Hophopname has been one of the most widely read books in Azerbaijan and in many other countries of the Near East.

Realism, tradition, satire

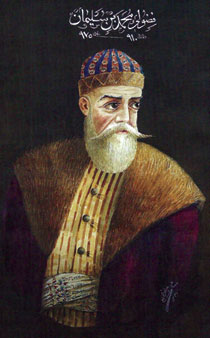

The realist portraits created by the artist in the period before Azerbaijan’s occupation by the Red Army are also notable works, especially the imaginative recreations of poet and philosopher Jalaladdin Rumi, military leader Salahaddin Eyyubi, and great Azerbaijani poet Muhammad Fuzuli.

The most fruitful period of Azim Azimzadeh’s work coincided with the 1930s. In this period the artist created his drawings of national life styles in his homeland and its religious traditions. He also worked on his very popular gallery of characters from Old Baku.

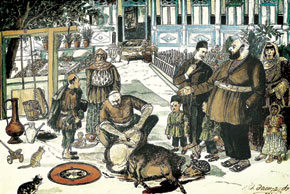

In his pictures reflecting the life and culture of the nation, the artist often used multilateral, parallel and contrasting frames to interpret the topics he illustrated, examples include: Wedding Party at the House of a Rich Man, Wedding at the House of a Poor Man, Ramadan at the House of a Rich Man, and The Fasting Holiday at the House of a Poor Man. The artist contrasted the grandeur, luxury and richness in clothing and the abundance at the table in the wealthy house with the miserable appearance, simple clothes and meagre table of the poor man’s house. Many posters were created to reflect the reality of the time and encourage thought. Contrasting colours and shades were used to heighten the effect.

Azimzadeh also illustrated the people’s customs and traditions in: Goch Doyushdurenler, Kos-kosa, Kendirbaz (Tightrope walker), It Bogushduranlar, Khoruzbazlar and others in which he displayed his sharp observational skills. Although the artist used comic effects in these works, in his drawings about the lives of women he applied dramatic means of expression. Again, the titles convey his concerns: Old Wife and New Wife, Forcing the Girl to Marry, Husband’s Tyranny, A Girl is Born in the Family, and Heavy Labour. More than simply observing the position of Azerbaijani women in public life and the family, he also delivered his creative response and communicated the drama of the situations.

His approach to the realities of life, embracing the often grotesque with bitter humour, was so immediate and arresting that it was impossible to remain indifferent. There was a persuasive purpose in depicting these aspects of society...

On street and stage

In 1937, the artist created his famous 100 Types series. He said that these works portrayed people that he met in the streets, markets and offices of Baku in the early 20th century. The series contained ten horizontal compositions each with ten images. Rich, vivid and memorable images of street dealers, rich merchants, people of various professions, officials, policemen, clerics, newsmen and teachers were provided in these pictures drawn side by side. The many imaginative types drawn by the artist all those years ago still provide models for artists working in theatre and cinema and trying to reproduce the Azerbaijan of the past. Azimzade himself provided stage designs and costume sketches for productions staged in Baku’s theatres, the variety was impressive: Uzeyir Hajibeyov’s musical comedy O Olmasin, Bu Olsun, his opera Leyli and Majnun and Zulfugar Hajibeyov’s Ashig Garib, Mirza Fatali Akhundov’s comedy Monsieur Jordan and the Dervish Mastali Shah and Jalil Mammadguluzadeh’s satire The Dead and many others.

Nothing in his hands but…

One of Azim Azimzadeh’s contemporaries, Aghabala Isgenderov, said,

When we worked together at the Baku Art school (Azimzadeh was director there for about ten years) he suggested we go to the charcoal-dealer´s bazaar. I did not refuse because he was the director and I was an ordinary teacher. Together we walked to the market and returned but he did not buy anything. This happened several times and when he again suggested going to the market, I objected. I said, ‘Uncle Azim, I feel ashamed. People will have ideas about two men who go to the market every time and leave without anything’. He replied, ‘What makes you think that I leave without anything?’ Saying that, he opened the drawer of the big table in front of him, and took out many drawings. I saw various images and types of people and understood why an artist goes to the market and returns ‘without anything’. It may be that he returned from the market with nothing in his hands but his eyes and mind were full of ideas. He understood that the people in the market would not understand him taking notes and drawing, so he simply observed and remembered the people he saw there...

Flushing out the clerics

When the artist touched upon on religious topics in his pictures published in Molla Nasreddin, religious people were upset. The critical points he made in such works as Struggle against Ramadan, There is No Place for Prejudice in our Industrializing Country, Pilgrims’ Fight and Solar Eclipse irritated them. Mullahs who used prejudice to keep people in fear, expressed their hatred of the artist in a very interesting way. His house was situated near a mosque and to exact revenge on him, the clerics built a toilet for the mosque by his house. Thus the Azimzade family periodically suffered its effects. People’s Artist and academician Mikayil Abdullayev (1921-2002) who was very close to Azim Azimzadeh in his youth, said that in response to the religious pressure, his friend draw caricatures of the mullahs on small pieces of paper and placed them at the entrance to the mosque in the evenings. When the mullahs saw these caricatures they became very angry, tore up the pictures and threw them to the ground. Mikayil Abdullayev acknowledged that,

Those pictures were so good that I sometimes took them home, not to let the mullahs rip them up.

Surviving Stalin, losing Latif

Azimzade’s diverse and creative work and the fame he achieved made him many enemies as well as friends. This became apparent during the repression of 1937. One evening, some people arrived in a ‘one-eyed car’ (a characteristic of the cars which took people from their homes to exile was to have only one light on in the evenings) and knocked at his door. The 57 year old had some difficulty in answering the questions of the security men. He was accused of cursing Lenin, Stalin and the party. The artist stressed that he was a member of the party, that such things did not tally with his age and he insisted that he had been slandered. At that moment, the inspector interrogating him called someone else into the room. The accuser was a former student whom he had helped many times.

Only the intervention of Communist Party leader MirJafar Bagirov secured the artist’s release, and he was not disturbed further.

Azimzade was very homely person. Even if he was very tired after work, he was always happy to be at home with his five children. He doted on them, especially his favourite Latif (1924-1943) who dreamed of becoming an oil engineer. Although he had reservations, Latif answered the call to war and his final letter arrived in February 1943. The artist’s daughter – Zahra khanim - who managed her father’s house museum for many years, said,

My father died because of the loss of Latif. The post worker gave me the notification of his death and I did not show it to anyone but waited for father’s return. We read it together. My father became very depressed and asked me to keep it a secret and not to tell my mother about it... After four months his heart could not stand the grief any longer and in June 1943 he died. The family learned about the heroism of Latif’s death much later...

Legacy and honour live on

In view of the popularity of his art, the government organized an exhibition at the House of Officers in 1940, during the artist’s lifetime. 1,200 of his works from various magazines were displayed. At an evening event organized with the exhibition the artist promised that he would serve the public with his combative art until his last breath. In the years following, notwithstanding advancing age and illness, he did not lay down his battling brush and created more and more new works. Sometime later exhibitions were also organised in Moscow and Irevan. While World War II raged Baku was supplying the forces with fuel, but everyone wanted to do their bit for victory. Information about the ideological struggle conducted by Azerbaijani artists and their compelling pictures exposing and criticising fascism reached the Kremlin and Stalin ordered an exhibition, Azerbaijani Artists in the War Years, held at the famous Tretyakov Gallery. Azim Azimzadeh was most prominent of the artists displayed. His drawings had particularly grabbed attention on the Agitprop Boards erected in the central streets of Baku and before the oil processing plant. The Lion and the Kitten, The Peacock Feathered Crow, The Fuhrer’s Trophies and The Ruins of Reichstag were some of the most memorable posters.

The memory of Azim Azimzade is still honoured. The Azerbaijan State Art School, which he directed, was named after him (it is now a college within the Azerbaijan State Academy of Art), a street in Baku also carries his name and the first house museum in Azerbaijan was opened to commemorate his life. His statue, by eminent sculptor Omar Eldarov, stands in Icheri Sheher (Inner City) the heart of Baku...