Pages 64-71

Pages 64-71by Tofig Babayev

Some of the myths, stories, customs and traditions, plays and spectacles connected with the Novruz Holiday - a new month, new year and the cherished first day of spring – have come down to us from the most ancient of days. These rituals and beliefs, whether traditional or scientific, have roots in the prehistoric past. Even then, people waited impatiently for, and cheerfully greeted, the arrival of spring, warm weather and nature’s renewal. The occasion was celebrated with animal sacrifices, singing, dancing and general festivity. Thus the celebrations originated in the ancients’ scientific and mythical ideas about death and the revival of life.

The Sumerians, who created one of the earliest forms of human civilization, developed a striking myth about the awakening of the earth, the recovery of nature and the beginning of the sowing season. From the myth it is clear that they performed annual ceremonies on the “death” (hibernation) of Dumuzi, the god of the plant kingdom, at the end of autumn and his revival in spring.

The Sumerians connected the “death and revival” of Dumuzi with sowing and husbandry; Dumuzi died – seeds were planted (buried), there was mourning on this occasion and the seeds were watered with tears; in spring he returned to life – seeds sprouted, nature revived, new life and a new day began.

The ancient Egyptians also had annual celebrations for the revival and return to life of the dead Osiris, the god of the plant kingdom, according to the husbandry calendar. Mythologies connecting changes in nature with various of their gods were widespread among the ancient Babylonians and other Eastern nations.

Zoroaster

The great Zoroaster created his own religion, with community of fire worshippers; among the seven important holidays devoted to Ahura Mazda[2], the spring holiday at the vernal equinox was particularly celebrated for the awakening and renewal of nature. This holiday, stretching back to times immemorial, focused on “Asha”, the immortal symbol of light and truth in the “Avesta”[3] and on Fire, the symbol of life.

On the last day of the year “Asha” finally defeats the forces of Evil. Zoroastrians also celebrated on Novruz, the New Day, the return of the “noon spirit”, who had walked the underworld during winter in order to warm the roots of plants and their sources. Thereafter, prayers were said every day at noon for the spirit who brought warmth and light back to the world.

Some connected the Novruz holiday with the names of certain historical and legendary figures. Although these legends have no historical basis, their existence speaks of the holiday’s importance in people’s lives and behaviour. The celebration was passed down the generations, to the day that Imam Hazrat Ali Ibn Abu Talib[4] claimed the caliphate throne, in 656. This indicates Novruz’ unique significance as one of the fire worshippers’ most cherished rituals prior to the adoption of Islam by the inhabitants of Iran, Azerbaijan and other places.

Thus Novruz, long celebrated by people living on the territory of Azerbaijan, was also accepted by succeeding religions and, in some cases, even valued as a religious holiday. Prominent Muslims of the Middle Ages referred to Novruz not for its religious status, but as a secular holiday of truly national, humane character and of benevolent, noble purpose. They declared it to be “a fine tradition transferred from generation to generation”.

Omar Khayyam

The great ХI century poet and philosopher Omar Khayyam wrote a treatise entitled “Novruznameh”, declaring it to be a unique public celebration. He narrated different legends associated with Novruz and their origins.

He included the traditions and customs commonly observed on the holiday.

He noted that Novruz was a genuine secular holiday based on the awakening of nature and the beginning of agricultural labour.

The famous ХI century Seljuk vizier Nizamulmulk, in his work “Siyasatnameh” (Political science) gave interesting information about the special place and weight of Novruz in people’s spiritual lives and confirmed the important role it played in public administration.

Nizamulmulk makes it clear that some days prior to the beginning of the holiday, heralds went round the cities, settlements, markets announcing the opening of the palace gates to the people. On the day of celebration, the people gathered in the palace and everyone lodged their complaints with the governor. Then the Padishah would descend from the throne and, kneeling before a priest, state: “Taking no account of my position, consider the complaint of this person about me impartially and pronounce sentence”. After this a court was set up and the complaint was considered. Its purpose was to help complainants, not to apply punishments, and nobody was off ended. Apparently, in ancient times even the severest governors were compelled to lighten their oppression on the day before the Novruz holiday.

Nizami Ganjavi, in his XII century work “Iskander-nameh”, (about Alexander the Great.) said that Azerbaijanis’ celebrated Novruz as a genuine national holiday even before Christ. He described the origins of Novruz and praised it in a literary form common to Azerbaijan poetry, ie. in lyrical verse (ghazals, odes, couplets), called bahariyya (about spring).

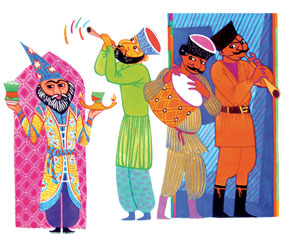

The German traveler, Adam O’Leary, who visited Shamakhi in 1637, had much to say about the arrival of Novruz. The traveler, a participant in the ceremonies, wrote: “the Astrologer often approached the table, observing the Sun by his own method, looking at the clock; thus he was waiting for the instant when the Sun would reach the point of equinox. As soon as the moment arrived, he declaimed: A New Year has come, a New Year has begun! A gun salute was immediately fired, pipers played on the city fortress walls and towers, and drumming began. This was the start of great folk festivities …”

Keeping the flame alive

Novruz differs from other holidays in its historical roots, essence and culture. Over the millennia, the Novruz holiday, with its ceremonies, customs and traditions, acts of kindness, oral folk tales, games and entertainments, has inspired the works of all ozans (or ashugs – Caucasian folk rhymers and minstrels) and poets, singers and performers, scientists and thinkers: from Dede Gorgud to Fizuli, Sabir, Samed Vurgun and Shahriyar.

Months, years and centuries replace each other, family roots spread, new generations are created, nations change, but our people, in spite of all bans, obstacles and fears, have treasured the Novruz holiday, keeping it alive as a sacred festival and cherishing its traditions.

Our ancestors, who had previously signalled the arrival of Novruz with fireworks, adapted to technological progress by firing gunshot salutes at the turn of a new year. Consequently, the “Novruz Salute” is summoned at “Year End”.

According to a popular belief still current among Azerbaijanis, the Novruz Salute brings in a new year under the sign of a certain animal. The character of the New Year is defined according to the characteristics of the animal. Scientists link this belief to the Mongolian and Turkic moon-sun calendars; thus, both Mongols and Turks grouped time into 12 year cycles, every year being named after a certain animal (rat, bull, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, cock (hen), dog or pig).

I will grow you every year

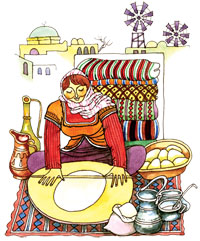

The growing of semeni - green sprouting wheat - is the most sacred Novruz ceremony as the herald of spring. Sprouting semeni symbolises sowing and a rich harvest, it represents grain, bread, increase and abundance.

Grain and abundance is a pledge of life, existence, the most vital material necessity for life. People have always grown semeni from wheat, barley, peas, lentils or other grains in copper dishes; they have always revered it and rejoiced at its sprouting.

Semeni, sprout well and even

Every spring

Remember me

This symbolism was also accepted by Zoroaster, and it came to be associated with his name. According to Zoroaster’s laws, people’s happiness lay in husbandry, and everyone was summoned to a settled life, to land cultivation, to fair labour. The “Avesta” said: “Whoever cultivates is engaged in sacred labour”. Concern for the earth, worship of the earth, sowing the earth and transforming it into a mother were the main requirements of the “Avesta”. In this ancient text the earth, addressing humanity, says: “O, man if you grasp me with two hands and cultivate me properly, then I will tirelessly create benefits for you, give you abundance and rich harvests. If you behave otherwise, if you do not labour on the earth, you will join the beggars and you will hang your head before the doors of strangers.

- What is the most important thing in the world?

- Sowing the earth with good, healthy seeds.

Observance of this law is equivalent to ten thousand prayers and to one hundred sacrificial animals”.

The Greek philosopher, writer and historian Plutarch (approximately 46-127AD) noticed that in ancient Azerbaijan (called Media) the regard for grain as a sacred plant was widespread. This tradition was realised at the beginning of every year (in spring). It is very interesting that this has survived to our time in the practice of growing semeni.

Semeni, please, protect me,

I will grow you every year!

Our ancestors, singing the gentle entreaty “Semeni, please, protect me …” asked semeni for protection, for prosperity. They promised: “I will grow you every year”.

The first heralds of spring

One ancient legend relates how the first announcement of Novruz was delivered by a gentle snowdrop, considered to be the most graceful of flowers. Warmed by the breath of the earth, it lifts its head from under the snow and in gentle voice joyfully announces: “Spring has come! Spring has come!” The violet with inclined head, the watermint and narcissus, as well as the snowdrop, impart the good news to all. Children and youth welcome a new day –“Violet Day” - when everybody goes to the foot of a fragrant hill, valley, southern slope or spring and collects wild flowers with great enthusiasm. Girls and brides decorate their hair and their clothes with violets; they spin wreaths from multi-coloured flowers which exude a magical aroma. Collecting bouquets of violets, they distribute them to their mothers and sisters with the words “they are spring’s first-born”, please, betrothed girls, make merry and sing songs:

I am violet with an inclined head,

I am violet with a broken heart,

I look out across the snow,

You, who have tasted troubles,

I breathe out a spring aroma,

I am fragrant as snow-white.

… Birds feeling the warm spring breeze return to their native land. Trees and roofs are bedecked with bird’s nests. Birdsong, trills, the hoopoe’s chirp, swallows, storks and titmice are heard from roofs and porches …

Cherished days of the year …

The arrival of spring brings in the favourite days of the year. These are days cherished for people’s folk celebrations. Our people prepare to meet these days with both pleasure and inspiration:

Novruz is coming, spring is coming,

Songs and fun are on their way,

May flowers blossom in the gardens,

May nightingales sing there too!

According to custom, our ancestors planted a tree for each member of the family during Novruz, they grew flowers and laid out orchards. In mountain and foothill areas the whole month of April was known as the month of green light.

Save the trees

A widespread popular belief held that ‘bailing out’ trees encouraged the production of fruit. As soon as the Novruz salute was fired people went to their fruit trees. One way to protect trees was for a man to carry an axe or a chopper as if he was going to cut down a tree. At this point an elder would approach him and ask: ‘Tell me, what you are going to do, why are you going to cut the tree down?’ – ‘It doesn’t produce fruit’ - was the answer.

Then the elder would advise: ‘Do not chop this tree, I will stand bail for it, it will bear a lot of fruit this year.’

In this way, all the fruit trees which regularly produced no fruit were frightened and were put on bail. Then a boy or a girl who was considered lucky poured sweets and fried wheat over the roots, watering them with sweet water. The whole family rejoiced, held a party and blessed the tree: ‘May your fruit increase, may your fruit be sweet.’ After that, a fire was kindled in the garden so that the wind carried its smoke towards the fruit trees. It was said that if the trees were not enveloped in smoke, the fruit would be rotten and empty inside.

As mentioned above, Zoroaster advocated husbandry and cultivation in the “Avesta”, writing of the beauty of vegetation and recognising it as the source of life. The book advises everyone to plant and grow at least three trees during public celebrations, weddings and holidays.

The great Dede Gorgud pronounced blessings such as “May your great shady tree be not cut”; he blessed men of courage and his compatriots and considered the “Cutting of a great shady tree” as the worst offence, as a sign of enmity.

Spring cleaning

Novruz is a triumph of cleanliness and health.

In order to greet these favourite days properly, good works are done throughout the country, improvements are made to villages, city streets and courtyards, roads are cleaned and houses are repaired. Accommodation is carefully cleaned and tidied.

Everything is put in order, house walls are whitewashed. Everywhere is radiant with cleanliness. People call it “house cleaning”.

Girls and brides clean their carpets and rugs, take them out into the open air, hang them on lines and fences, beat the dust out of them, leave them to air in the sun, with the wish that friends may rejoice in their prosperity and foes may be afflicted.

Many rites and ceremonies are fulfilled on sacred Novruz eve. Eavesdropping at doors, promenading in the courtyards, putting caps outside the doors (to be filled with goodies – ed.) and lowering shawls down flues were ancient rites which have survived until now. The great poet Shahriyar praised these rites as follows:

It was a holiday, the night bird sang,

The bride was knitting her groom’s socks,

Everywhere shawls were lowered down the flues,

How beautiful is the ceremony,

To treat the groom with festive sweets.

The householder took a shawl and wrapped into it a red egg, fried peas and wheat, nuts, filbert, raisin, oleaster, almonds, pistachios, dried apricots, dried fruit and a lot more besides; the shawl was lowered down a neighbour’s flue. Sometimes the shawls became too heavy. As grandmothers, mothers and brides included a pair of socks with pompons, fragrant soap, a towel or something else. While treating neighbours and relatives in this way they always wished them abundance and prosperity.

“Eavesdropping at doors» was basically a rite of the youth, who made wishes and tried to learn their destiny. The purpose of this rite was to hear words of goodwill. If the eavesdropper heard a pleasant word their wish would come true. Consequently on that evening everybody tried to talk about pleasant things, not to use bad words at all. There is a saying that “Who laughs at Novruz will laugh the whole year”. The blessings and wishes of grandmothers and grandfathers are heard from houses.

Be Sweet

On Novruz eve it is forbidden to be gloomy, to behave badly, to drink wine or to use bad language. It is said that “Allah will not bless those who speak rudely on such a joyful day”. As the actions, wishes, thoughts, behaviour of all are refreshed, spirits are elevated on that day. For betrothed girls, the eve of Novruz means presents; they are sent decorated trays fi lled with various sweets. Colourfully dressed women, girls and brides carry the trays covered with fringed and flowered shawls. They are followed by the eyes of the neighbourhood … The custom of sending trays continues still. With the approach of twilight the fireworks begin; fires are kindled in the squares and courtyards. Everyone gathers around festive tables adorned with every possible pastry delicacy: gogals (savoury rolls of thin layers of pastry), pakhlava (baklava – a rich sweetmeat consisting of thin layers of pastry, filled with nuts and honey), shekerburah (patterned pastry, with nut stuffing), crumbly cookies, badamburah (a sweetmeat of puff pastry with an almond stuffing), bamiya (a pastry delicacy), fasali (puff rolls), halvah (made from sesame paste) with nuts and filbert, gurabiyah (almond cookies). You also will find on the tables fragrant sherbet, trays of different sweets, dried fruits and delicacies, and coloured eggs. Pan lids are raised to reveal steaming plov (pilaff), relatives and neighbours are treated. It is difficult to imagine a festive table without dishes of fish, a symbol of pleasure and fun. Fish bring abundance, said our ancestors. People in need are helped, food is sent round to their homes.

The centrepiece of every family’s table is semeni. Words of praise are recited and ancient songs sung in honour of fresh green semeni:

Flowers have blossomed, spring has come,

Birdsong is heard,

Snow-white has turned to green

All is revived,

Mountains are covered with flowers,

Gardens are flower bestrewn,

White and red,

How beautiful is the spring!

Neighbours and relatives send semeni to each other. On the table it is surrounded by candles: one for every member of the family. Candles are lit at the moment the old year ends and the new one begins. Researchers connect this to the sun, which the ancients perceived as heavenly fire; with fire on the earth being its representative. With the arrival of the New Year, everyone sits down at the festive table.

Novruz is a holiday of poetry, songs and love for humanity. These well-loved days are dressed in new attire. The elderly smarten up, dress up. Children, young men, girls and brides also put on bright, holiday dress. Single girls and boys search for their beaus and belles and exchange vows of love.

A new start

At Novruz generosity, mercy and kindness triumph. People forgive insults, halt reproaches, try to reconcile quarrellers, people abandon mourning. It is forbidden to swear, tell lies or gossip. Everybody visits each other to avoid trouble or enmity. People become more affable and careful. It is customary for people to remember their departed dear ones in their prayers.

Parents who wish their own children to be fresh and healthy, name babies born at this time in honour of the ancient, national holiday; with such beautiful names as Novruz, Bayram (Holiday) or Bahar (Spring).

Everyone congratulates each other, wishing many happy returns and sending folk greetings – ‘May your life have the aroma of spring. We wish you good, bright mornings’.

At daybreak on the first morning of spring everybody would go to the river and wash thoroughly, leaving all hardship and fear in the water. Girls and brides, young guys, elders, made wishes and jumped over water, “dumping heaviness”, easing the burdens of life.

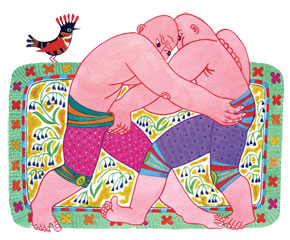

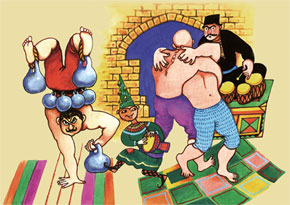

In the course of the celebrations, brave men show their courage, combatants tussle, try their strength, horsemen jump onto their horses and arrange races, they compete in shooting arrows. Wrestlers and strongmen display their skills.

Swings hung from high plane trees and majestic oaks; lines were drawn for a game called “diradoymah” in open areas. Children made “horses” out of reeds for themselves and skip backwards and forwards, calling to the sun: “Sun, come to our side, shade, go to the mountains, Sun, come to our side, shade, go to mountains”.

“Chiling-agach”, “Mara-mara”, “Enzeli”, “Papagaldigach” were favourite children’s games. Rope-walkers gave thrilling performances. Crossed poles were erected in open areas and connected by a tightly stretched rope. The rope-walker held a long pole in his hands and danced on the rope accompanied by a zurna (oriental wind instrument) and kettledrum, showing his acrobatic prowess. His assistant, called “kechepapag” (‘holder of the woolly hat’), entertained people below, clowning around and making them laugh.

The egg - symbol of life

From the very dawning of the Novruz holiday, eggs have been dyed red and egg cracking competitions held. This custom still exists and is another children’s favourite; it has been turned into an amusing ditty:

Stoned egg,

Stone, stone …

Head egg,

Head, head …

Uncle Gadzhi

Was angry

Broke a whole basket of eggs

Stoned egg,

Stone, stone …

Eggs were specially selected to be banged together, alternately by the blunt and sharp ends. 20-25 eggs were put in line; one was taken from one end, another from the other end and they were banged together.

Whoever broke the most eggs collected the broken ones and celebrated as the winner. The game was won by cunning and skill: “You hold, I’ll strike”, “I’ll have this one, you take another”, “Let’s change eggs, then we will play”, “Let’s taste it”, “No, your eggs are warty” etc.

In most cases the eggs of a speckled chicken won:

My chicken was white,

My chicken was fat,

May you burn, who stole the chicken,

May you blaze, who stole the chicken.

… From time immemorial the egg has been considered a symbol of life and the creation of life by many nations: there is also the belief that, as in life, both good and evil can hatch from an egg.

Experts on the Middle Ages thought that egg embodied the four elements, symbolic of the material world: the shell symbolised the earth, the lining symbolised air, the white represented water and the yolk was flame. This symbolism explains why the egg came to be used in these and other ceremonies in many countries.

- But why are the eggs dyed?

Different nations reply to this question according to their religions, beliefs and ways of life. Ancient Azerbaijanis connected the red colouring of eggs with the worship of fire. Red symbolises fire, the sun and flame.

Spring shapes the year

The first four days of spring were highly significant and were connected to the seasons. The first day was called yazdan (spring), the second was called yaydan (summer), the third day was called payizdan (autumn), the fourth day was called qishdan (winter). According to some beliefs, the weather during these four days determined how these four seasons would be. If the first day was soft and sunny, it meant that spring weather would be favourable.

If the second day was wet and windy summer would also be rainy. If there was rain and high wind on the third and fourth days, people would make dolls and promenade, singing songs to summon the sun. However, the ancients believed that cloudy, rainy weather during the first days of spring was a reason for joy. It was not rain that poured from the clouds, but wellbeing and abundance; let it pour - it meant that Novruz had not come with empty hands. People went to the sowing fields, raised their hands to the sky and declared “Thanks to God, thanks to God, God grant that this year is fertile”.

Let high water flow on the roads

On roads, on inflows

Let pour it on the fields,

On the fields and the meadows.

That is why our ancestors said knowingly … “The farmer’s barn is filled by spring rain”.

And there is one more saying:

“Spring defines the luck of a year”

About the writer:

Tofig Babayev

Senior Staff Scientist at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography under the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Azerbaijan.

The author of a series of books and articles, including the monograph - “Folk gather at the hearth (historical-ethnographic sketches)” (Baku, 1998)

Notes

1. Novruz Bayram – New Year Holiday

Pictures by Ismayil Asad oglu Mammadov

2. Ahura Mazda - The God of the monotheistic Zoroastrian religion

3. Avesta – The Zoroastrian sacred text

4. Imam Hazrat Ali Ibn Abu Talib - the first Imam for Shia

Pictures by Ismayil Asad oglu Mammadov

.jpg)