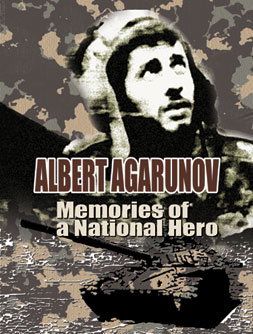

The night of 8-9 May 1992 was dark and cold. There was no sign of a military attack. There had been only occasional firing from the enemy on Azerbaijani soldiers defending the city. It was past midnight when intelligence reported an offensive movement by the Armenians. However, no one was expecting a large-scale offensive. That night many valiant sons of Azerbaijan died. They died defending Shusha, the pearl of Azerbaijan and bastion of national culture. Albert Agarunov, a 23 year-old tank commander, was among those who gave their lives.

The night of 8-9 May 1992 was dark and cold. There was no sign of a military attack. There had been only occasional firing from the enemy on Azerbaijani soldiers defending the city. It was past midnight when intelligence reported an offensive movement by the Armenians. However, no one was expecting a large-scale offensive. That night many valiant sons of Azerbaijan died. They died defending Shusha, the pearl of Azerbaijan and bastion of national culture. Albert Agarunov, a 23 year-old tank commander, was among those who gave their lives.Born into a Jewish family…

A brave guy according to his comrades, Albert was devoted to his country and died pushing his courage and determination to the limit. He was born into a Jewish family in the village of Amirjan, near the capital Baku. His family was originally from Qirmizi Qasaba (Red Settlement) in Quba and had moved to Amirjan in search of a better life. Albert’s father had found work in the oil fields nearby, and a new life had opened up for the Agarunov family. His mother, Leah Agarunova bore and brought up ten children. She was later awarded the title Heroine Mother. She was not to know then that years later her youngest son Albert would become a National Hero, or at what price...

On that terrible day for a mother

The day after Susha was occupied, no one of the Agarunov family in Amirjan was expecting terrible news. On the contrary, they were all awaiting a happy occasion – Albert had promised to arrive from the front, from Shusha, where he had been serving for some time. It was late morning when the phone rang. Leah picked it up and, expecting to hear her son’s voice, she heard instead …We are so sorry – this last phrase has remained sharp in her memory.

Later she would remember the day when her dear Albert was preparing to leave for Shusha after his last leave. How could she know she was seeing him for the last time? That was in April, a month before the terrible news reached Amirjan. Agababa Gasimov, his comrade-in-arms and a neighbour from the yard was, by chance, with Albert then. First they dropped in on Albert’s home. Leah had cooked a lot of qutabs, her son’s favourite Azerbaijani dish, to feed him up and to send some for his comrades in Shusha. When will you be back? –she asked him. – I don’t know mom, I’ll try to come on my birthday. A week later he called home and apologised for not coming on his birthday, 25 April. But he promised to arrive on 15 May. The whole family had started to prepare for his arrival. The news came a week before that date and the colour drained from their lives.

In search of the truth

Several versions of Albert’s death have been reported in books and news articles. Visions of Azerbaijan decided to find the truth and began its own investigation. First we visited Baku’s synagogue in search of relatives but none are here now; almost all of them moved to Israel several years ago. Then we were advised to visit school No. 154, located in Amirjan and named after Albert. It was so quiet, the school seemed deserted, as if the war had closed it too; there was just the monument to Albertm, standing alone by the school entrance. Perhaps nothing was to disturb the rest of the deceased soldier, even the lessons in progress. We entered the building; the whole wall on the second floor was hung with posters and photographs of soldiers who had died in the Karabakh war. Albert’s picture was among them. How many young lives this war had claimed…

This was the school he attended, but we couldn’t find a teacher who had known and taught him. Director Ali Aliyev had arrived at the school long after Albert’s time there.

But we can introduce you to Agababa Gasimov, his comrade-in-arms who lives here in Amirjan and who visits every year on the anniversary of Albert’s death he told us in his office. Agababa was called and asked if he would come for an interview. We were pleasantly surprised when he agreed. We were no less surprised when we met a slim man with a thoughtful expression who had stopped everything to talk to us about Albert.

The Three Tankers Song

The middle-aged and older generations will remember this Soviet song learnt at schools in the post-Soviet republics, including Azerbaijan. It is about three brave tank soldiers who fiercely defended their homeland against the fascists. While Agababa was sharing his memories of the Karabakh war, I certainly recalled this song. Albert, Agababa and Sarradj, the third member of their tank crew, were always together.

It was probably fate that we met each other during a war, although we were from the same settlement. Even stranger for Albert and I – we went to the same school, worked in the same factory and, finally, served in the same military tank unit in Akhalkalaki, Georgia. I was 8 years older than him. We often saw each other in the village, school and factory, but hadn’t met personally or knew that we were in the same unit. Later, when we met and became comrades-in-arms, we often joked about it. I called him Alik and he called me Aga. We became very close – I, Albert and Sarradj. It could be said that we were among the first Azerbaijani tankers in Shusha during the Karabakh war.

Funny stories saved us in the war… I remember an episode too often; it will never leave my mind. One day our scouts were sent towards Khankendi (the administrative centre of Karabakh) to reconnoitre the land. Then we heard that the scouts had been ambushed. Without a second thought we decided to go to their aid. About ten scouts were ambushed and they all needed help. Our aim was to prevent supplies going to the Armenians who had launched the ambush. So, our tank was ordered to go to the scouts and we prepared for battle. When the enemy escort drove up with provisions, Alik aimed at several targets. We usually shared targets among us to coordinate our attack. However, in that attack Alik didn’t give the rest of us any chance to confront the enemy; he destroyed the escort by himself very quickly and very precisely. No wonder he was famed as a good marksman. Afterwards, we cracked a lot of jokes about it.

The Armenians were afraid of him and put a price on his head

When we went to the front as volunteers we were not properly armed, two soldiers even had to share one Kalashnikov. Many guys went to the front simply not to be at home, because it was considered shameful for a man not to go. We were ready to clean barracks, peel potatoes and wash floors just to stay in the army. And that’s what we did. Months passed before we got a tank; it was a T-72, number 533. Very soon, number 533 was popular in our unit and even the Armenians feared that number. They hated Albert more than other Azerbaijanis and often asked each other

- Why is this Jewish guy fighting so bravely? Is it his homeland he is ready to die for it?

Only then did we learn that they had put a huge bounty on his head. Albert knew about it and he just laughed, which made the Armenians angrier. I remember an interview with Chingiz Mustafayev, the famous Azerbaijani journalist who died heroically in the Karabakh war: Albert threw out a phrase which silenced the Armenians completely. He said:

- I’m fighting for my homeland where I was born and where I grew up. My wish is to restore peace and freedom to the territory of sovereign Azerbaijan.

He really was a very brave man. While we were defending Shusha, our crew destroyed about 10 tanks and IFVs (infantry fighting vehicles), dozens of armoured trucks and supply trucks. Albert’s skill was in shooting quickly and accurately.

The last hours of life…

It is so hard for me to go back to those days, the day when Alik died. He was the first martyr from our detachment. Vagif Mekhbaliyev, another brave member of the detachment was killed the same day. Those two losses affected us badly; it took us a long time to recover. It all started at 2 a.m. on 9 May 1992. Our intelligence reported that Armenian troops were going to attack Shusha that night. We were put on alert. Obviously, we were accustomed to such alerts. We thought that the Armenians would shoot a little and then quieten down, as usual. We hadn’t faced a strong attack before that night and we had no idea how it would turn out. After 2 a.m. the Armenians prepared their artillery. By early morning, at 7 a.m., it was clear that they had prepared a serious attack on our positions. It was clear that they were planning to occupy Shusha. Our tank stood on the outskirts of the city. We knew what was happening when dozens of enemy tanks began to move up to the outskirts. Alik managed to knock out one tank. There was a long battle. When we ran out of shells we had to back up to stock up on ammunition. While we were back, it was evident that we were losing our positions. However, our soldiers were standing to the end because we didn’t want to believe that we were losing. We just didn’t believe it. Alik began to shoot even more fiercely. And what I remember most is his cheerfulness and confidence that inspired all of us. He was so calm, he stood on the tank hatch so confidently. I told him several times not to do it but he didn’t listen to me. Our resistance continued for another hour. Then I noticed that Alik wasn’t giving any signals. I went up and saw him lying face down on the hatch. At first I thought he had just fallen and lost consciousness. I called to him several times and then I crawled over to him and started to shake him. I turned him over; there wasn’t a spot of blood on his body. A moment later, I found a hole in his back. The bullet had penetrated at the left shoulder and was sloping down to the heart. He was dead. It was a sniper’s bullet. After that I remembered nothing; it was as if I was mentally broken. He loved his tank so much – the 533. And he died on it. It was the first tank to enter Shusha to defend the city. Now the 533 is standing in Baku, in the yard of the Salyan barracks.

May his memory live forever!

That was Agabala Gasimov’s story, from a soldier who went through the whole Karabakh war and who stored everything in his heart. Dozens of years have passed but still the sounds of gunfire and explosions ring in his ears. He holds a desire to someday return to Shusha and see it at peace and free, as Albert had wished.

To be honest, I don’t want war. I don’t want the young generation see war. If it breaks out again let us – the greybeards - go to fight. We have seen it once and we aren’t afraid of seeing it again. Let our young people fight in the educational field, not on the battlefield. And let them not forget our National Heroes like Albert Agarunov.

Albert Agarunov was 23 when he died. He was posthumously awarded the title of National Hero of Azerbaijan and was buried at Martyr’s Avenue in Baku in May 1992. Let the path to his grave never grass over. And may his memory live forever!