Jeffrey Werbock made his first appearance on Azerbaijani television some twenty-four years ago when this was still part of the Soviet Union. He journeyed from his USA homeland and first set foot on Azerbaijan soil shortly afterwards. Since then has been a regular visitor and an even more regular performer in the West of the traditional instruments tar, kamancha and oud and the mugham music they play. He is an enthusiastic campaigner for the recognition by name of the beautiful carpets produced in many regions of the country. On 3 November last year, Azerbaijan paid unique tribute to this man who has helped so much to promote its music to the wider world. The cultural great and the good assembled to help Jeffrey celebrate his 60th year. The event was, of course, televised, but the main pleasure was to be had in Baku’s Mugham Centre listening to the tributes spoken, played and sung, and reflecting on the warmth of feeling between an American and a culture he first glimpsed in California. We asked him to explain his creative journey and the attraction of Azerbaijan. Here is the second of his three-part explanation.

Jeffrey Werbock made his first appearance on Azerbaijani television some twenty-four years ago when this was still part of the Soviet Union. He journeyed from his USA homeland and first set foot on Azerbaijan soil shortly afterwards. Since then has been a regular visitor and an even more regular performer in the West of the traditional instruments tar, kamancha and oud and the mugham music they play. He is an enthusiastic campaigner for the recognition by name of the beautiful carpets produced in many regions of the country. On 3 November last year, Azerbaijan paid unique tribute to this man who has helped so much to promote its music to the wider world. The cultural great and the good assembled to help Jeffrey celebrate his 60th year. The event was, of course, televised, but the main pleasure was to be had in Baku’s Mugham Centre listening to the tributes spoken, played and sung, and reflecting on the warmth of feeling between an American and a culture he first glimpsed in California. We asked him to explain his creative journey and the attraction of Azerbaijan. Here is the second of his three-part explanation.The Cosmopolitan World View of Caucasian Azerbaijanis

For many centuries the lands now called Azerbaijan were part of what is known as the Persian Empire, because the rulers of this area during much of the last millennium were Azerbaijani Safavids and Gajars who also spoke Persian in addition to their native Turkic-Azerbaijani language. When the Caucasus was conquered by the Russian Empire in the mid-nineteenth century, the northern part of Azerbaijan began to leave the sphere of influence of the culture associated with the Persian language and enter the sphere of Russian speaking peoples. Soon, virtually all the ethnic groups of the Caucasus spoke the Russian language, which had a strong impact on the people living in the area now called the Republic of Azerbaijan.

The majority of ethnic Azerbaijanis live in Iran and while almost all of them speak Persian, not all speak Azerbaijani and almost none speak Russian. The next largest grouping is found in the Republic of Azerbaijan, the oil-rich post-Soviet republic making its way out from under centuries of imperialism, dictatorship and authoritarianism. Many speak Russian and nearly all speak Azerbaijani, but few speak Persian. English is slowly becoming a third language in Azerbaijan.

Iranian Azerbaijanis generally attribute the difference between themselves and their northern cousins to the Russian influence, including language, in the Caucasus. There is no doubt that language has the power to mold and reinforce certain distinct cultural traits, but in reality it is not easy to find an Azerbaijani from Azerbaijan who has really, in his or her heart, fully assimilated into Russian culture. The difference they perceive has much more to do with the indigenous cultures of all the peoples of the Caucasus (Kavkaz in Azerbaijani), rather than an overtly Russian cultural influence.

Fellow feeling

One of the most intriguing social characteristics of the Russian-speaking Kavkaz Azerbaijanis is their attitude toward other nationalities. I am not talking about hospitality, a highly evolved social instinct among all groups in this part of the world. I am talking about real feeling for others who are not like themselves. Excepting those who have betrayed them, Kavkaz Azerbaijanis exhibit a degree of cosmopolitan grace toward others that I believe may be unmatched in the world.

It is possible that Kavkaz culture and environment may be the reason for this, given the near impossibility of inter-village travel during winter, and the joy of receiving a guest with fresh news of the outside world that is easily worth sacrificing a sheep for. In any case, it is unlikely that the Russian culture brought this feature of society to Azerbaijan. In general, Russians are not nearly as pleased by others as Kavkaz Azerbaijanis seem to be.

One anecdote not meant to prove anything, but illustrative of the cosmopolitan world view and solidarity with outsiders demonstrated by Kavkaz Azerbaijanis, comes to mind:

During one of my visits to Baku, the father of the Azerbaijani student who lived with us in the USA invited me and about two dozen of his friends to dinner at an open air restaurant within the ancient fortress walls of the old city. There were two long tables in the central courtyard, one occupied by our group, the other by a gathering of expatriate oil workers, mostly from the British Isles. At one point during the dinner, my host and his friends insisted that I play music for them, and this put me in a difficult position, owing to the raucous behavior of the expatriates who, unlike Azerbaijanis, do get noisy and drunk when they drink a lot of alcohol.

I tried to pass on this, because the surrounding conditions seemed incompatible with the mood of mugham. My hosts refused my attempts to decline their request and so, somewhat reluctantly, I walked to the little stage with my kamancha, took the microphone and spoke in English, patiently explaining to the loud folks at the other table that I was being pressed into service by my Azerbaijani friends, a duty that cannot be refused without permanent damage to my relations with them. I implored my fellow English speakers to please refrain from talking for ten minutes while I attempted to render in these raucous conditions what I consider sacred music.

Amazingly, they stopped talking, and some even turned to listen to the music. Of course, after some minutes of music the bubbles of conversation started floating into the sound space again from the ex-pat table, but I have to hand it to those ruddy revelers so far from home, they did keep it down, for the most part, during this mild ordeal for all of us.

Kavkaz Jews

One curious feature of Kavkaz Azerbaijanis that really sets them apart is their positive regard for Jewish people. Not only do they not have any anti-Semitic feeling in them, they look down with contempt upon people who do.

For many a Kavkaz Azerbaijani, the Jewish person represents something of an ideal, especially the European Jew. There are many indigenous Kavkaz Jews who look and act nearly identically to Kavkaz Azerbaijanis. They speak fluent Azerbaijani, and they participate fully in every aspect of Azerbaijani culture. They are generally regarded as equals by the majority Shi’a Muslim Azerbaijanis. But the European Jew is a breed apart, and for some reason deeply buried in the collective psyche of Kavkaz Azerbaijani society, held in high esteem.

During the 11th or 12th century – historians, please pinpoint this issue once and for all – there was a Jewish dynasty called the Khuzars, or Khazars, that ruled over the Caucasus for more than one hundred years. I suppose that could have something to do with this peculiar phenomenon, or it could be attributed to the fact that in the early years of Soviet domination, their capital city Baku was only 30 per cent Azerbaijani and 70 per cent other nationalities like Russians, Armenians, various Europeans, other Asians, and Jews, both European and Oriental.

The demographics have changed radically over the years and now Baku is at least 90 per cent Azerbaijani, but their cosmopolitan outlook and tolerance for others has not changed. Azerbaijanis have a kind of weary, worldly-wise attitude toward life, always hurt when injustice happens, never much surprised by any of it when it does.

When you get the chance, look into the eyes of an Azerbaijani. Except for older persons and children, you have to be the same gender or all sorts of misunderstandings will crop up. But if you do, you will see a light, a flickering fire of consciousness that is entirely independent of learning or training. It is an inherited glow, and you can see it easily in children who have yet to learn to hide anything.

Azerbaijanis are the mystic poets and musicians of the Kavkaz peoples. Azerbaijani children have the torch of that history and culture passed onto them by their parents and grandparents. The old argument of nature vs. nurture as the prime determinant for an individual’s character and abilities has to be examined in the light of this phenomenon. I don’t think a Kavkaz Azerbaijani child can manifest the same cultural genius if raised in another country, nor will a non-Azerbaijani raised in Azerbaijan be able to reach such heights of artistic sophistication.

The miracle of mugham

Am I singing praises too loudly? Please go to the website www.mugham.net and watch the video clips of untrained Azerbaijani villager children who were expelled from their homelands and forced to live in refugee camps owing to a civil war with ethnic Armenians living in western Azerbaijan. One clip in particular stands out because the boy singer appears to spontaneously compose his own poetry while rendering perfectly one of their most complex and sophisticated mughams, Segah. He tells of his longing for his lost homeland, and even though he knows there is nothing left but ashes, his heart still yearns for those ashes.

Toward the end of this inspired outburst of patriotic poetry, he chokes back a sob, but one tear escapes, and as he wipes it from his eye, he informs us in song that the reason he is crying is because he was made a stranger in his own land.

Let’s take a breath and step back from all the social and political ramifications manifested in this example which you will, hopefully, see and hear for yourself and focus exclusively on the artistic genius of this boy – perhaps 13 or 14 - who is nothing more or less than a good example of his culture.

Mugham, from my perspective, is spectacular. Played or sung by a child, it is impossible. That means this boy and his song is a miracle, and as far as miracles go, it is far enough for me. But the miracle is not confined to one child or one village. It is not a matter of one or two child prodigies. It is across the land. It is a manifestation of a uniquely Azerbaijani cultural phenomenon, a kind of local cultural genius.

Why then, we can ask, are there not more examples of Azerbaijanis who have made world class status, artistically?

Well, Mstislav Rostropovich was born and raised in Baku, and many regard him as one of the greatest cello players and orchestral conductors in the world. But he was born a Russian Jew, not an Azerbaijani, so it may not be accurate to include him in this. Gary Kasparov, the grand chess master, comes to mind. He too was not an ethnic Azerbaijani, but he was a great talent from Azerbaijan. The Azerbaijani jazz pianists Vagif Mustafazade and his daughter Aziza are well known in jazz circles. But these examples of great talent, especially in the arts, do not speak of the eastern side of Azerbaijani society, although Vagif had said his jazz is informed and inspired by mugham.

Azerbaijan and its indigenous culture have been, and remain, a mystery to the rest of the world, so it is most unlikely that anyone other than those few Azerbaijanis who have made their mark in western idioms will emerge from obscurity to take their rightful place on the world stage.

The greatness in traditional Azerbaijani art culture is virtually unknown to the world, and this irony is not lost on the people. It is part of their sociology, this quiet acceptance that what is great for them is ignored by the rest of humanity. Perhaps I have detected an undercurrent of, ‘…if they only knew, but that is not our fate…’ So when some outsider does take note, as happens from time to time; they have a great appreciation for that person. And that capacity for appreciating the outsider who does take notice of the greatness of some aspect of their culture is itself an integral part of the Azerbaijani way of being.

I have attempted to redefine the distinct culture of Kavkaz Azerbaijan from a Russian influence to a Caucasian influence. The presence of Russians in the Caucasus has contributed something to the unique cultures found in all the regions there including Azerbaijan, but the much larger influence comes from the peoples of the Caucasus themselves. And there are so many, such diversity, yet there is something they seem to have in common. To illustrate what that something is, let me describe what could be the aspirations of different cultures and compare them to Kavkaz.

Respect is…

In America, to be respected, you have to be accomplished. Of course it matters how you achieved your success, and it is always better to have played by society’s rules, but first and foremost, it is that you have accomplished something, and for that you deserve respect.

In old Europe, there is something even more important than accomplishment, and that is knowledge. Those who are known as worldly-wise receive more respect in Europe, and that is partly why older people get more respect in Europe than in America.

In old India, it matters little what you have done or how much you know. What is important is how detached you are from the things of this world. This is changing fast, but it was not long ago that a common sight was a near naked man on a mat, besieged by a line of well wishers bringing gifts and asking for blessings. No one got more respect in old India than a venerable, otherworldly, detached and holy old man.

In Persia, respect went to those who could rhapsodize and wax poetic in all circumstances of life, even of only offering or asking for a cup of tea.

In the Caucasus, no one cares what you did, how much you knew, nor how lovely your speech was, and being detached would earn you a nickname, not respect. What counts here is your self-possession. This is such an odd concept for us that I feel compelled to explain. Self-possession means you don’t get excited over every little thing in life. You are quiet inside. You don’t manifest yourself in a way that crowds out the presence of others. And you carry yourself with a dignified sense of your own presence that is not put on for the sake of others, but is a natural attribute of your general state.

When a person in the Caucasus - usually of advanced age - who is self-possessed walks into the room, everyone instinctively rises to their feet, gently places their right hand over their heart, nods their head just a little, and sends a silent or quietly uttered greeting of welcome and respect tinged with awe. It doesn’t matter what the venerable person’s gender is, all that matters is the degree of self-possession. And it is not just a matter of advanced age, although that is enough to set the stage for a high value to be afforded that person who is also palpably in possession of themselves. But it is not a personal affair. It is their culture, concentrated in and manifested by the individual who is both a repository for this cultural feature and a conduit to pass it on. This reverence for self-possession permeates all aspects of the cultures found in the Caucasus. At the same time, there is a heavy streak of romanticism in these peoples. The dynamic tension between these two polar opposite human tendencies brings an intensity to life that is remarkable. In Azerbaijan, the land of fires, this intensity finds expression in music and song like nowhere else on earth.

Mysticism in the History of Azerbaijan

There is a place in Azerbaijan called Gobustan which features an unusual geological formation that has many traces of Paleolithic society. Cave paintings and carvings similar to the famous ones in Lascaux, France adorn the walls of these strange formations. There are boulders the size of bathtubs that ring like they were made of hollow metal when struck, emitting musical tones. Some people believe that there is a kind of mystical energy emanating from the rocks and hills that one can feel when sitting still upon them. It is possible that self-suggestion accounts for this phenomenon but, more importantly, the fact that this belief exists in Azerbaijan tells us something about Azerbaijani society. I was taken to Gobustan by a businessman whom no reasonable person would ever associate with mysticism, but there we were, sitting on the slope of a hill overlooking the sea, when he asked me if I could feel the energy rising from my seat and spreading throughout my body.

His question startled me because he asked it after a certain period of quiet contemplation, and just before he asked, I was marveling at the effects of sitting there in this unusual place. It seemed as if the geological forces that formed this place were still active, like a gentle pressure or warmth that one can feel, but only when one’s mind is sufficiently quiet.

His question startled me because he asked it after a certain period of quiet contemplation, and just before he asked, I was marveling at the effects of sitting there in this unusual place. It seemed as if the geological forces that formed this place were still active, like a gentle pressure or warmth that one can feel, but only when one’s mind is sufficiently quiet.Scientific explanations aside, what is of primary interest for me is how such a highly educated people can also sustain this vein of mysticism running through society. I knew one person, a professor of physics at a local university, who clearly believed in supernatural forces and respected them, understanding that science cannot explain everything.

Fire and philosophy

Thousands of years ago, something ignited the natural gas percolating through the porous rock from underground deposits, and to this day there is a patch of mountainside that is on fire, mostly small blue gas flames sputtering across the ground with an occasional orange jet shooting up in the air from a sudden increase in pressure. Ancient pre-Azerbaijani fire worshippers built temples around these phenomena which attracted pilgrims from as far away as India.

Evolving into a rather complex ideology, fire worship was the precursor to a religion known as Zoroastrianism. Attributed to a prophet-like figure named Zartosht (Zoroaster, Zarathustra), this religion worshipped heat and light as representing the forces of good in the world and cold and dark as evil. Their god was Ahura Mazda, and they celebrated the coming of the days of more light and less dark, the vernal equinox, with bonfires.

To this day millions of Azerbaijanis thrill to the challenge of jumping over a pile of burning materials gathered from the surroundings, a few occasionally getting injured. It is quite a sight to be driving around Baku on the nights before Novruz, their New Year celebration, where bonfires send flames up into the air on city streets. Wherever one turns, the fires are burning on every block.

The overall impression is as if one had suddenly left the modern age and was back in a period of great antiquity when life was precarious and conquerors with invading armies were the norm, when whole societies appeared and disappeared along with their antiquated beliefs. Yet we were in a car driving through a relatively modern city surrounding an ancient core. One doesn’t often get to use the word ‘surreal’ in life and really mean it.

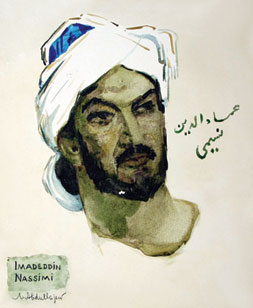

Waves of various belief systems have passed through this area over the centuries and all of them were rooted in deep mysteries, including the major religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Sufis and dervishes were well established in the southern Caucasus, adding layers of mysticism to the ancient fire worshipping culture. There was the famous mystic Jalaluddin Rumi originally from Balkh, and his teacher Shamsi Tabrizi of Azerbaijan, who brought to Turkey the practice of whirling to achieve a transformation of consciousness. Another century saw the mystic figure of Azerbaijan, Nesimi, a name which means fresh breeze.

Persecuted as a heretic and charged with apostasy against Islam, Nesimi preached the doctrine of ‘I AM’. His message, in a nutshell, was: unless I feel I exist, it doesn’t matter what I believe or practice. This was the quintessential existential philosophy grounded in the mystical experience of the physical self. I AM. Not the thought I AM, which is the commonest thought of all, but the sensation I AM, the rarest of rare sensations.

Close to ‘I AM THAT I AM’, the ancient Hebraic formula for the name of their God, Yahweh, which centuries later morphed into the Christian Jehovah, the doctrine of I AM became a call to spirituality that challenged entrenched dogma. Nesimi was skinned alive for promoting this practice, turning himself in to the authorities in order to save another, a devoted follower who was willing to play impostor and sacrifice himself for his master’s safety.

For millennia the land now called Azerbaijan was saturated in mysticism, ecstatic visions and transcendent practices. Music was always part of that milieu and still is today, even though it has drifted somewhat from its original transformative powers toward performance art. In mugham we can still feel the power of this legacy of mysticism, which continues to exert a strong gravitational pull on the socio-psychology of Azerbaijani people.

For millennia the land now called Azerbaijan was saturated in mysticism, ecstatic visions and transcendent practices. Music was always part of that milieu and still is today, even though it has drifted somewhat from its original transformative powers toward performance art. In mugham we can still feel the power of this legacy of mysticism, which continues to exert a strong gravitational pull on the socio-psychology of Azerbaijani people.At first glance it appears that most Azerbaijanis are preoccupied with practical issues such as material wealth, politics and local history. But underneath all that is a current of deeper longings. Scratch the surface of any Azerbaijani and you will find at least a philosopher if not an outright mystic who views the world as an inexplicable, unknowable and unpredictable event that is ruled by fate and invisible forces.

It may not be possible to prove that this beneath-the-surface mysticism is due to Azerbaijanis long traditions which include the state-transforming music of mugham, but the connection seems obvious. And since most Azerbaijanis are secular people, it can’t be attributed to some prevailing religious ideology.

A fire that does not burn….

The irony of such a modern educated class of secular people also having deep convictions in a world view that includes invisible forces acting upon people and directing their lives can only be properly understood when seen in the light of their long-held traditions of mystical practices and beliefs. The spectacle of a physics professor burning herbs and reciting incantations to ward off evil spirits is a sight to behold. It is unclear the role that mugham plays in such a paradoxical world view, if any, but it is probably not just coincidence that this is a common phenomenon in Azerbaijan, both land of fires and birthplace of mugham.

Even more intriguing than the maintenance of folkloric mystical beliefs among a highly educated and cosmopolitan population is the phenomenon of living with inner intensity. Azerbaijanis have a fire inside that burns brighter than the pyres scattered around the countryside that gives rise to the name, Land of Fires. It is the people themselves that are on fire, and you can see it in their eyes. But it is a fire that does not burn. It warms everything inside.

A waiter says to his patron, ‘Nush-e-jan’, a phrase that can hardly be translated into English because we don’t have such a feeling in our limited repertoire of emotions for others. It means not only may you enjoy the tasty food, but also may it nourish your soul. It is said with the same feeling of a mother feeding a child. The word hospitality is a poor label for this generosity of spirit.

It is a phrase not to be delivered with a casual attitude. It is said with an inner intensity that will be hard to find elsewhere, if it can be found at all. Where does this inner intensity come from? And who besides Azerbaijanis know about it? Over the years that I have come into contact with various expatriates living in Azerbaijan, there are those who have fallen in love with the country and its people, and of course there are those who come to work and live and then leave when the contract expires and hardly notice where they have been, which is in the center of a hearth of human warmth.