After the First World War, the Paris Peace Conference (18 January 1919 – 21 January 1920) set out to redefine international relations and the Republic of Azerbaijan, having declared its independence on 28 May 1918, had high expectations. Independent Azerbaijan was the first modern secular republic in the Muslim world. It relied on the Peace Conference to help with strategic issues such as recognition by Western countries, equal membership of the international community and guaranteed territorial integrity.

After the First World War, the Paris Peace Conference (18 January 1919 – 21 January 1920) set out to redefine international relations and the Republic of Azerbaijan, having declared its independence on 28 May 1918, had high expectations. Independent Azerbaijan was the first modern secular republic in the Muslim world. It relied on the Peace Conference to help with strategic issues such as recognition by Western countries, equal membership of the international community and guaranteed territorial integrity. The Soviet threat

From the very first day of its existence, Azerbaijan feared becoming a colony of Soviet expansion. The Soviets wanted to reinstate a united Russia within its former borders. The founders of the Republic of Azerbaijan were well aware of the threat took every opportunity to draw the attention of the international community to their young republic’s situation. They wanted recognition as an independent country, subject to international law with all the concomitant political and security guarantees. At that historical point they needed an intensive campaign to build political-diplomatic relations based on mutual interests with the international community, especially with Europe.

One of the first meetings of the Azerbaijani Parliament held in December 1918 decided to send a delegation to France. On 28 December the government selected a delegation to represent the country at the Paris Peace Conference. Ali Mardan bey Topchubashov, Chairman of the Azerbaijani Parliament, was elected head of delegation. Mammad Hasan Hajinsky, another member of government, was elected his deputy. The delegation also included other members of the parliament – Ahmad Bey Aghayev, Akbar Agha Sheikhulislamov, Mir Yagub Mehdiyev, Mammad Meherremov and Jeyhun Bey Hajibeyli.

The representatives of the Azerbaijani Government were guaranteed participation in the international peace conference during negotiations with General W. Thomson, commander of the Commonwealth Army in the Caucasus, in November 1918. General George Milne, an official representative of the British government on a visit to Baku, confirmed this in statements.

However, once the Azerbaijani delegation arrived in Istanbul on 20 January 1919, they faced many difficulties obtaining visas to Paris. The conference started on 18 January 1919 but the Azerbaijani representatives were not given visas to France until 22 April, whereas the Armenian and Georgian delegations had been in Paris long before. At last, immediately before US President Wilson was to officially introduce Azerbaijani issues at the conference, the delegation was urgently invited to Paris. They left Istanbul on 22 April and arrived in Paris on 7 May.

Busy schedule

They immediately began work to achieve recognition for Azerbaijani independence. The chairman, Topchubashov, and other members of the mission conducted active negotiations: presenting materials about Azerbaijani history, culture, economic resources and relations with neighbouring countries.

The delegation actively promoted their country’s political and economic interests, especially urging recognition and guarantees of security. In preparation for the conference, thanks to the work of the diplomatic mission, the Azerbaijani Republic had launched several initiatives to build mutual relations with the USA, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Iran, the Ottoman Empire and other countries.

During May the delegation held meetings with the representatives of Poland, Georgia, the North Caucasus Mountain Republic, Armenia and Iran. They met Sir Louis Mallet, a member of the English delegation, on 23 May. On 28 May, the republic’s first anniversary, Woodrow Wilson received the delegation headed by Topchubashov, who gave the US President detailed information about Azerbaijan and presented him with six requests: to recognise Azerbaijan’s independence, to apply the Wilson Principles to Azerbaijan, to allow the Azerbaijani representatives to join the peace conference, to include Azerbaijan into the League of Nations, to give US military support and to establish diplomatic relations between Azerbaijan and the US. Negotiations resulted in an agreement to send a special American mission to the Caucasus. However, the mission arrived in Baku very late, in October 1919. At the meeting President Wilson stated that the USA could make no commitment regarding states that had become independent of Russia and that he saw no necessity to divide the world into small countries.

Wilson’s non-committal answers did not end the hopes of the Azerbaijani delegation. They made their official requests of the conference in the document Memorandum of the Delegation of the Caucasian Azerbaijani Republic to the Paris Peace Conference. It was 50 pages long, divided into 14 sections and written in English and French. This document was the culmination of hard work by the delegation, each point reflecting Azerbaijan’s national interests.

The delegation’s demands

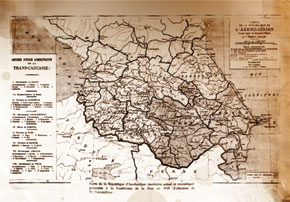

One of the most important concerned territory and population. The territorial claims made to the conference by the Armenians, Georgians and Iranians were of concern. Thus, it was vital to establish the proper borders of Azerbaijan for the conference leaders. The territory of Azerbaijan was drawn up according to the former system of executive division:

1. Baku Province, including Baku city, as well as Baku, Javad, Goychay, Shamakha, Quba and Lankaran districts.

2. Yelizavetpol (Ganja) Province, including Yelizavetpol (Ganja), Javanshir, Nukha (Sheki), Arash, Shusha, Jabrayil, Zengezur and Qazakh districts.

3. Irevan Province, including Nakhchivan, Sharur-Dereleyez, Surmeli districts, as well as a part of New Beyazid, Echmiadzin, Irevan and Alexandropol districts.

4. Part of Borchali, Tbilisi and Sighnaq districts in Tbilisi Province.

5. Zaqatala district.

6. Part of the territories surrounding Kurina and Samur in Daghestan region, as well as part of Kaytag-Tabasaran district including Derbend City and its surroundings.

7. In the above-mentioned Irevan and Tbilisi Provinces, as well as in Zaqatala district, there are very small territories whose origins have been the source of claims from Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia and Northern Caucasus Republics.

Lloyd George, Vittorio Emanuele Orlando, Georges Clemenceau and Woodrow Wilson at the Paris Peace Conference. 191

Lloyd George, Vittorio Emanuele Orlando, Georges Clemenceau and Woodrow Wilson at the Paris Peace Conference. 191The memorandum on territories noted that the Republic of Azerbaijan attached special importance to the inclusion of Akhalsikh district and the districts of Batum and Qars in Tbilisi province to its territories.

The memorandum also makes clear that the indisputable territories under the control of the government of the Republic of Azerbaijan were 83,786.6 square versts or 94,137.38 square km. This constituted 39 percent of the entire territory of the Caucasus of 217,408 square versts or 247,376.15 square km.

The memorandum ended with the requests of Azerbaijan from the Peace Conference:

The peace delegation of the Republic of Azerbaijan wishes to make the following requests of the peace conference: that the peace conference approve the separation of Caucasian Azerbaijan from the Russian Empire; that Azerbaijan become a fully independent state with the borders shown on the map attached to this memorandum and known as the Republic of Azerbaijan; that members of the peace delegation of the Republic of Azerbaijan be involved in the process of the peace conference and its commissions; that, as with many other states, the Republic of Azerbaijan become a member of the League of Nations, under whose protection it wishes to stand.

Return of the Russian Empire?

One of the biggest obstacles to the recognition by the peace conference of Azerbaijani independence and to the obtaining of guarantees for its territorial integrity was the Allies’ approval of the idea of a ‘united and undivided Russia’. Agreeing to the indivisibility of Russia blocked recognition of independence for Azerbaijan. The first serious support for Russian unity from the Allies was the recognition in June 1919 of the Kolchak government for all the lands of the former Russian Empire. The first – strong – reaction to this came from the Azerbaijani delegation. Each member of the Azerbaijani delegation personally voiced strong words of protest. They addressed the heads of the Supreme Council of the conference and Entente countries, acting jointly with other countries that were against the idea of a United Russia.

In fact the Azerbaijani diplomats did not fight for independence for only their own country; they also urged independence and political unity for the whole Caucasus. In modern terms, they were supporters of the idea of the Caucasus House. During the approval of documents, the Azerbaijani delegation worked in the interests of the whole Caucasus, acting jointly with the representatives of Georgia and the North Caucasus Mountain Republics. The Armenians opposed the idea of the Caucasian House, maintaining their campaign for a Great Armenia. Thus it was impossible to realize a concept that was so crucial for the political, economic and moral unity of the nations of the region.

Looking West

Ali Mardan beyTopchubashov understood perfectly well that guarantors of Azerbaijani freedom came not only from Europe but also from the other side of the ocean, the USA. He managed to build close relations with the Americans in a very short time. He made agreements with the advocate Walter Chandler and Max Rabinoff, representative of the American Jewish community. He gave them the authority to represent the interests of Azerbaijan in the USA and Canada. Books published in Paris about Azerbaijan (in French and English) were sent to those countries in 1919.

Topchubashov believed that the establishment of Azerbaijani lobbies in the USA and Europe was the means to guarantee recognition of Azerbaijan by the international community, as well as securing reliable protection of its political and economic interests. Thanks to the efforts of the delegation, objective information was presented on many topics: the history of Azerbaijan, the country’s rich natural resources, occupation by Russia and oppression by Armenian, relations with neighbours in the Caucasus, the factors contributing to the Armenian-Azerbaijani confrontation, the massacres of Azerbaijanis carried out by the Dashnak-Bolshevik alliance in Baku in 1918, and many others. This helped to make Azerbaijan better known in the West and at least partially correct the wrong impressions of Azerbaijan prevailing as a result of Russian and Armenian propaganda.

Despite all the difficulties, the Azerbaijani delegation’s difficult struggle for justice at the Paris Peace Conference was not in vain. British Prime Minister Lloyd George delivered a speech to parliament on 12 November 1919 noting the possibility of recognizing the independent states of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia. This statement by the British head of government drew strong objections from Russian immigrants in Europe. Nevertheless, a letter by the French chairman of the foreign policy division of the League of Nations dated 17 November stated their intent to recognize the de facto and de jure independence of Azerbaijan and Georgia. The US State Department’s attitude towards Azerbaijani independence had also changed for the better. All this created a basis for the Republic of Azerbaijan to join the League of Nations. In December 1919 the Azerbaijani delegation prepared a memorandum on membership of the League of Nations and presented it to the League secretariat, which created a special commission chaired by Chilean representative Antonio Huneeus Gana to study the issue. The territories of the Southern Caucasus countries were not considered to be stable, thus the question of admission to the League of Nations was postponed.

The tide turns

In late 1919 there was a revival of international discussion about the Caucasus and Russia in general. This followed a retreat by Tsarist generals in their struggle against the Soviet government. Towards the end of 1919 it became clear that the attempt to resist the communist takeover in Russia by the White forces had almost failed.

White Guard leader Yudenich failed in an attempt to capture Petrograd. Kolchak had advanced deep into Siberia. Denikin, leader of the White Guard advance on Moscow in 1919, was giving up cities one by one and moving back south. Azerbaijan and Georgia had long been under threat from Denikin, however, the defeat of his army created a new, even more dangerous situation for Azerbaijan. They now faced a stronger enemy – the Bolsheviks.

During negotiations with the US Under Secretary of State Frank L. Polk in Paris at the end of November 1919, Lloyd George clearly stated to the American side that there was no point in helping Kolchak and Denikin. Their defeat was clear and all the arms and ammunition sent to them had been captured by the Red Army. Lloyd George added that a united, Bolshevik Russia would represent a huge threat to Europe. Thus he strongly supported the idea that:

the independence of Georgia, Azerbaijan, Ukraine, Bessarabia, the Baltic states, Finland and possibly Siberia should be recognized.

The question of the Southern Caucasus republics was discussed in the context of the general Russian issue at a meeting of the Prime Ministers of the Entente countries held in London in December 1919. The heads of the leading countries regretted the failure of the Russian generals, but they were hesitant about adopting Great Britain’s position. This said, they did not know how to proceed. They shared the view that they should attempt to arrange peace between Azerbaijan and Georgia and General Denikin and organize their joint protection. Azerbaijan and Georgia refused to participate in a block with Denikin. At the same time, the general held that those countries could not be involved in negotiations as independent foreign states. Denikin’s aim was to reinstate Russia within its 1914 borders.

Reception at the Ministry of Internal Affairs on the recognition of Azerbaijani inderendence by the Paris Peace Conference. January 192

Reception at the Ministry of Internal Affairs on the recognition of Azerbaijani inderendence by the Paris Peace Conference. January 192Recognition at last

A session of the Supreme Council of the Paris Peace Conference was summoned on 10 January 1920 on British initiative. Among the participants were heads of governments and ministers of foreign affairs from England, France and Italy, delegates to the peace conference and ambassadors of the USA and Japan to France. The question of the Southern Caucasus republics was broadly and thoroughly discussed at the session held at the Quai d’Orsay. The meeting of the Supreme Council was continued in the afternoon by ministers of foreign affairs, without Lloyd George and Georges Clemenceau. British Foreign Minister Lord Curzon initiated discussions on the political aspects of the situation in the Caucasian republics. Curzon stated that Lloyd George intended to raise the recognition of Azerbaijani and Georgian independence at the Supreme Council, while the Armenian question was to be discussed together with that of Turkey. Curzon suggested that it was an urgent necessity to recognize Azerbaijan and Georgia de facto. The next day the Supreme Council of the Allies adopted a decision based on Curzon’s proposal:

The Allies and joint countries recognize the governments of Azerbaijan and Georgia de facto.

This was the Azerbaijani delegation’s main achievement in the international arena. News of this historic event reached Azerbaijan on 14 January. On the same day the Azerbaijani parliament held a ceremonial meeting and organized holidays throughout the country and a general pardon was declared. Later members of parliament and their guests oversaw a military parade.

The delegation had achieved their main objective. They had delivered exactly what the nation desired: the recognition of the Azerbaijani state by the international community. It was now a political reality. When the Bolsheviks recaptured the country and made it part of the Soviet Union on 27 April 1920, they had to deal with this fact.

Worth the struggle

The 23-month long existence of the Azerbaijani Republic and the successful foreign policy of that period meant that the Soviet Union could not ignore the de facto recognition of the country or divide Azerbaijan into districts and provinces once more. If the Republic of Azerbaijan had not at least partially achieved international recognition for 1918-1920, the establishment of Socialist Azerbaijan would also have been in doubt.

It is true that it was not possible to preserve Soviet Azerbaijan within the borders of 1918-1920. A number of Azerbaijani lands that were under the control of the national government or that were the subject of dispute at the peace conference were given to other ‘fraternal soviet republics’ by agreement with the Bolshevik government. Terrorist action was conducted against the Azerbaijani National Army. Democratic institutions still in their infancy ceased to function. The state symbols of independent Azerbaijan – the tricolour flag and the anthem – were banned. High ranking officials of the national government and political activists were pursued. However, despite all the repressive measures enacted from April 1920 and continued for more than seventy years, the idea of Azerbaijani state independence could not be erased from the memory of its people. Azerbaijan finally regained its independence in 1991.

Literature

1. Azerbaijan in the Paris Peace Conference (1918-1920). Compiled by Vilayet Quliyev, Baku, 2008.

2. Hasanli J. Foreign policy of the Nations Republic of Azerbaijan (1918-1920). Baku, 2009.

3. Nasibzadeh N. Foreign policy of Azerbaijan (1918-1920). Baku, 1996.

4. Qafarov V. Azerbaijani issue in the Turkish-Russian relations (1917-1922). Baku, 2011.

5. Topchubashov A.M. Formation of Azerbaijan, Istanbul, 1918.

6. Topchubashov A.M. Paris letters. Information of the Peace Delegation of the Nations Republic of Azerbaijan to the Government of Azerbaijan (March 1919-November 1919), Baku, 1998.

7. Address-calendar of the Republic of Azerbaijan, under the editorship of A.M. Stavrovsky, Baku, 1920.

8. Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan (1918-1920), Foreign policy, documents and materials, Baku, 1998.

About the author: Vasif Qafarov is a professor at Baku State University. He has a PhD in History and is the author of the monograph The Azerbaijan Issue in Turkish-Russian relations (1917-1922) and various articles about the period.