The spread of Islam in Azerbaijan was naturally bound up with the social and economic life of the nation and its struggle against the tyranny of both foreign invaders and local governors. Inscriptions on cultural monuments offer important clues about just how quickly and under what conditions these developments took place. In fact, sometimes the only information we have about particular movements, ideas, societies, and significant Muslim clergymen is from inscriptions. They may be short, but they are extremely valuable historical documents.

The spread of Islam in Azerbaijan was naturally bound up with the social and economic life of the nation and its struggle against the tyranny of both foreign invaders and local governors. Inscriptions on cultural monuments offer important clues about just how quickly and under what conditions these developments took place. In fact, sometimes the only information we have about particular movements, ideas, societies, and significant Muslim clergymen is from inscriptions. They may be short, but they are extremely valuable historical documents. These inscriptions help us to understand the forces that spread Islamic ideas and to place them in a chronological framework. They also help us to understand Islam’s role in people’s struggle against exploitation. (1, 3) One such inscribed monument tells of Seyid Ahmad Badavi, who had a leading role in the defeat of Louis IX’s crusade, which was achieved by uniting the forces of the Islamic world (4, 115, 116; 3, 196; 5, 180, 181). He was an Egyptian holy man whose real name was Ahmad Ibn Ali, but he gained fame as Seyid Badavi. He was born in 596 AH (1199 AD) in Fez, and he died in the city of Tanta in Egypt in 675 AH (1276), where his tomb still stands. Successors to Al–Ahmadiyya al–Badaviyya functioned in Azerbaijan until the 19th century. The epitaphs of sheikhs at places of pilgrimage in the northeast of Azerbaijan prove that Azerbaijani scholars were familiar with Seyid Ahmad Badavi. (2, 40)

Unity and equality

In 1798 Egypt was invaded by Napoleon and tsarist Russia was looking to the Caucasus. This factors required Sufi sheikhs to work to unite the forces of the Islamic world. Ahmad Ibn Idris and Ahmad al-Tijjani stressed that the purpose of praying was not to reach God, but to join the spirit of the prophet Muhammad in the struggle for Islam. (3, 93 – 94) Thus the society established was called Ahmadiyya - Muhammadiya. There are still Ahmadiyya – Muhammadiyas in Sheki today.

Islam is more than just a collection of religious ceremonies. It also directs social standards, with guidelines on how to live one’s everyday life. In the 7th century, the prophet Muhammad united the religious ceremonies of all of the tribes of Arabia. He declared the equality of all people and said that anyone who violated this principle had to answer to God. This notion of equality played an important role in the expansion of Islam, firstly among Arabs and then among other nations. Arabic was the language of politics, science and education in all states of the caliphate. Islam had a profound impact on the culture and the fine arts of these states. (1, 5)

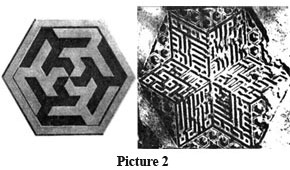

Wherever Islam spread, cities experienced revival. Inscriptions describing this revival use the same geometrical tracery and botanical motifs. This new, intricate ornamentation became the language of images and ideas for the whole Muslim world. (7pic. 40 – 43, 73, 109a, 114, 126,127, 130 – 133, and b; 2, pic. 449, 457, 492; 8, pic. 968 – 985, 992, 971 – 975, 1055)

Inscriptions as instruction…

The concept of monotheism established cultural, social and political unity from the states of the Arab caliphate to Kashkar (on the western borders of China) and Japan. Islam connected a range of nations with different languages, races, cultures, lifestyles and religions, and gave them a set of common cultural and legal norms. (1, 5) Islamic tenets propagating the ideas of monotheism and promoting a higher morality to people, were engraved in the form of panels and trimmings on architectural monuments and tombstones. Such inscriptions were used as a visual means of propaganda; they were aesthetically pleasing and had a deep psychological impact, inculcating humanism, goodwill, fairness, mercy, respect for others and faith in one God. (1, 5)

Later, when the Caliphate weakened, local feudal states were established in the Near East, including Azerbaijan. Local governors who accepted the Islamic religion invested in the enlargement and reconstruction of a range of cloisters of social, economic, and cultural importance. They were responsible for sacred graves, shrines, mosques, ecclesiastical schools (madrasas) and other complexes together with towers, castles and other civic property. Inscriptions placed on buildings as well as on memorial monuments were written in Arabic as a rule and ended with ayahs (verses) from the Qur’an and hadiths (saying or action attributed to the prophet Muhammad).

Later, when the Caliphate weakened, local feudal states were established in the Near East, including Azerbaijan. Local governors who accepted the Islamic religion invested in the enlargement and reconstruction of a range of cloisters of social, economic, and cultural importance. They were responsible for sacred graves, shrines, mosques, ecclesiastical schools (madrasas) and other complexes together with towers, castles and other civic property. Inscriptions placed on buildings as well as on memorial monuments were written in Arabic as a rule and ended with ayahs (verses) from the Qur’an and hadiths (saying or action attributed to the prophet Muhammad). And as record

Again these inscriptions are a help in understanding the purpose and history of the monuments. One example is the tomb in the of the palace of Shirvanshahs’ palace complex that Shirvanshah Farrukh Yasar had constructed for himself. Some researchers had believed it to be a treasury or court house and building for carrying out executions. However, the incompleteness of patterns on the pavilion’s columns and the entrance panels, the empty grave, and the 25th and 26th ayahs of the 10th sura (chapter) of the Qur’an written on the door in the southern section of the rotunda, all prove that the building is a mausoleum. The ayahs say:

Allah invites to the House of Peace and guides whomever He wills to a straight path. For those who have done good there is goodness, and more. Neither gloom nor shame will shadow their faces. These are the inhabitants of Paradise, abiding therein forever.

It is clear from information in the work of the historian Huseyn that Farrukh Yasar was defeated in war by Shakh Ismayil in 1500. Shakh Ismayil ordered that his hands and legs be bound. He was then burned alive. That is why he was not buried in the mausoleum that he had built for himself. (9, 322 b)

As Islam was the state ideology, the aristocracy, merchants and others were afraid of the influence of the faith and gave great presents and donations to higher Muslim clergymen and cloisters situated on the trade routes. The sheikhs of the cloisters spent the money from those donations on the construction of buildings, providing living spaces for followers, for overnight stays by strangers, and room for caravans. They provided safe havens along the caravan trade routes, as these caravanserais were constructed at distances of one day’s travel and were supplied with reservoirs of water.

The social and religious centres that arose on the trade routes attracted attention from neighbouring states as cultural centres and were pivotal in social, political and cultural relations between the different countries. As seen from the inscriptions, such centres were associated with Sufism. This complex philosophical movement was thus spread widely throughout the Islamic world. (10. 13, 41)

Pir Huseyn, Sufi sheikh

The Sufi societies Galandariyya, Gadiriyya, Bektashiyya (and its branches Babai and Chalabis), Khalvatiyya, Nagshbandiyya (and its offshoot Alaviyya) all functioned in Azerbaijan from the 11th to the 19th centuries. Of all the cloisters connected with Sufism, only the Pir Huseyn cloister has survived. Pir Huseyn was sheikh of the Galandariyya Sufi society, and his cloister is on the bank of the Pirsaat River, along the Baku-Salyan caravan trade route, 127 kilometres from Baku. The Government of Azerbaijan declared it to be a museum on 1 October 2007.

Pir Huseyn was important to the history of scientific philosophical thinking in Azerbaijan and the development of an Islamic philosophical world vision. (1, 8 – 13) He lived to a very advanced age, dying 25 years after his older brother Muhammad Bakui, in the year 467 AH (1074/75). Al-Huseyn ibn Ali, known as Sheikh Pir Huseyn, was referred to in the cloister’s inscriptions as a great seyyid (saint) who reached the third level in Sufism (Al-Salikin). He achieved the title of imam and was involved in confessional work. Thus he was considered to be a seyyid in his time.

Pir Huseyn was important to the history of scientific philosophical thinking in Azerbaijan and the development of an Islamic philosophical world vision. (1, 8 – 13) He lived to a very advanced age, dying 25 years after his older brother Muhammad Bakui, in the year 467 AH (1074/75). Al-Huseyn ibn Ali, known as Sheikh Pir Huseyn, was referred to in the cloister’s inscriptions as a great seyyid (saint) who reached the third level in Sufism (Al-Salikin). He achieved the title of imam and was involved in confessional work. Thus he was considered to be a seyyid in his time.The monuments in the cloister complex, surrounded by a fence with high towers, reflect the grandeur of the Middle Ages. Every inscription dating from the 13th to the 15th centuries indicates the importance of this cloister. They chronicle various events in the history of Azerbaijani culture. The complex includes a mausoleum, mosque, minaret, caravanserai and other constructions. They are considered to have some of the examples of Shirvani and Absheroni architectural design from the Middle Ages.

According to the inscriptions, most of the cloister buildings were constructed in the time of Fariburs, the son of Shirvanshah Garshasib, and Garshasib II, the son of Akhsitan II. V.A.Krachkovskaya assessed the cloister thus:

The glazed trimmings of the Pir Huseyn tomb may be compared only with the mausoleum of Imam Rizah in Mashhad. (19,104)

Mongol support and destruction

One inscription on a minaret in the Pir Huseyn cloister notes that in the time of Mongolian ruler Mongke Khan, his governor Arghun Agha (1284 – 1291) made regular donations to the cloister.(7, 46 – 47, № 53) Arghun Agha was the governor of Khorasan, Persian Iraq, Azerbaijan, Shirvan, Georgia, Lur, and Kirman. (11, 121)

By the early 13th century, European states and the Pope in Rome were very much concerned about an Islamic invasion of Jerusalem. In 1245 they called a council and decided to wage war against Muslims in Europe and the Near East with the help of the Mongols. In order to annihilate the Caliphate and Christianize the Near East and Iran, they decided to Christianize the Mongols. The Armenians from Cilicia played an important role in the implementation of the Pope’s plan. In 1253, the Prince of Cilicia Hethum I (1227 – 1270s) went to Karakorum at Mongke Khan’s invitation to obtain official status for the union established between them. Notwithstanding the efforts of the European countries and the Pope, the Mongols accepted Islam, not Christianity.

The carriers of this ideology were the higher Muslim clerics. As they settled conflicts between the government and the people in favour of the people, they had great social influence. Even tsarist Russia understood this and included Muslim clergymen into the administrative structure of government. (13)

In order to strengthen the power of the Ilkhanids and the Golden Horde, the Mongol governors accepted Islam and visited the cloisters. The Khan of the Golden Horde, Ozbek, returned the property of the Pir Huseyn cloister which had been seized during his attack on Shirvan. (14, 637; 11, 326) According to the Persian historian Vassaf, 30,000 sheep and 20,000 cows and donkeys were returned. Some women and men living on the cloister’s endowed lands had been enslaved. (14, 326)

Pir Huseyn was a follower of the Sufi sheikh Abu Said Abu-l-Kheyr the Galandar who was active in Nishapur. The word Galandari in Arabic has five letters. The letter G – means saving, the letter l – means honour, n and d – mean self-control and closeness to God, and the letter r – means asceticism. Those who became members of the Galandari society had to obey certain conditions.

Pir Huseyn was a follower of the Sufi sheikh Abu Said Abu-l-Kheyr the Galandar who was active in Nishapur. The word Galandari in Arabic has five letters. The letter G – means saving, the letter l – means honour, n and d – mean self-control and closeness to God, and the letter r – means asceticism. Those who became members of the Galandari society had to obey certain conditions.The cloister of Sheikh Babi Yagub, a Sheikh of the Sufi Galandariyya society, is situated in Fuzuli region in the village of Babi, six kilometres from Horadiz railway station. The village is still named after the Sheikh.

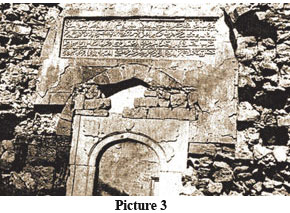

When we worked there in the 1960 and 70s, the Sheikh’s octagonal tomb, a badly damaged minaret, a mosque and the remains of a fence surrounding the complex were all that remained. The Arabic inscription on the entrance to the mausoleum reads:

Construction of this holy mausoleum was ordered for the perfect Sheikh Babi Yagub ibn Ismayil Gurkhar, the hermit, in the year 672. Everything earthly will perish.

The year given, 672 AH, corresponds to 1273 – 1274 AD.

Religion a challenge to society

According to the twelfth century historian Fazlullah Rashid ad–Din, the people’s movement in Karabakh that began under the leadership of Babi Yagub went beyond its ideological framework and took on a military-political character. Rashid ad – Din wrote about the Ilkhani governors contacting his followers in Aran. He said that Sultan Ahmad Takadur greatly respected the followers of Babi Yagub. (15. 104, 108;7, 127, 128, № 54) Describing events that place between 1282 and 1284, he wrote that when Arghun, the brother of Sultan Ahmad, spoke out against him, Sultan Ahmad asked Babi Yagub and his followers for support. (15, 104, 108) It is clear from his writing that although Sheikh Babi Yagub died, his followers continued his campaign.

We might suppose that this movement was widespread, not only in Aran and Karabakh, but also in other parts of Azerbaijan. It played an important role in the development of an Islamic philosophical worldview, also influencing the political, economic, social and cultural life of the people in Azerbaijan. As the inscription names Sheykh Babi Yagub as a son of Ismayil Gurkhar, we might also suppose that he was related to the Ismailis.

Abu–l–Futuh al–Hasan ibn al–Malik al– Hamadani, who became famous under the pseudonym Gurkhar, was the nephew of Ismaili ideologist Hasan Sabbah. At the beginning of his career, he was an imam of Gazvin city. Later he accepted the doctrine of the Batinis. Shiah imams and the Sunnis of Gazvin accused him of bidat (irreligious innovations). He escaped to Alamut, which was the main fortress of Ismailis, and became one of their most famous propagandists. The Ismaili movement in Azerbaijan has not been investigated but it is clear from all historical sources and research that it had close connections to Azerbaijan. In Iran this movement, as one of the extreme currents of Shiism, was directed against the feudal nobility, Seljuks and Mongols, which is also true of events in Azerbaijan. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, most support for the Ismaili movement came from artisans and the rural and urban poor. Sometimes, Iranian nobles united with them in their struggle. (16, 50)

The Ismaili movement spread to the northern provinces of Iran (Deylam, Jurjan, Tabaristan, Kuhistan) and to Azerbaijan, resulting in the formation of a state centred on Alamut in northern Iran (1090 – 1256). (17, 60) Inscriptions, including the stone inscription in the mausoleum of Babi Yagub, indicate that the Ismaili movement was widespread – in Karabakh, Aran and other provinces of Azerbaijan.

Piri Mardakan, answering the questions

There is a large monument connected to the Galandariyya Sufis in Goylar village south-east of Shamakha, on the ancient Shamakha – Javad – Ardebil route. Piri Mardakan became quite well-known and was visited by many travellers, including the 17th century German scholar Adam Olearius. From travellers notes it seems that the Piri Mardakan complex was both trading stop and pilgrimage camp, but it eventually fell into decline. Only the mausoleum now remains. The foundations of a cell, mosque, caravanserai, and other buildings have been unearthed and there was also a large cemetery nearby.

Until recently years, researchers were still seeking answers: Who was buried in the tomb? Why is the monument called Piri Mardakan? Does it have any connection to the Mardakan settlement in Absheron?

Two inscriptions in the tomb answer these questions and clarify its name and age. They also help determine who was buried in a tomb visited and regarded as sacred, his position as a political figure and a scholar and other issues. The Arabic inscribed on the stone tomb translates as:

In the name of Allah the most merciful and beneficent. This grave belongs to the sheikh, imam, great scholar, and devout Tair Taj al–Huda Madakani ibn Ali. Rest in peace.

The epitaph does not have a date. But, the second inscription connects the mausoleum to the governance of Farrukhzad I, the son of Shirvanshah Manuchehr III, 600 AH (1203/04 AD).

The attributes ‘devout’ and ‘sheikh’ and the position of imam all indicate that Alim Taj al–Huda was the imam of a dervish centre.

Medek is a place in Azerbaijan, 27 kilometres south-east of Hasanabad. The suffix -ani indicates that the scholar, Imam Sheikh Tair Taj al–Huda was from Medek. Other Sufi dervish centres functioned on Azerbaijani lands: Sheikh Zahid (XIII) in the village of Shikhakeran in Lenkeran region, Seyid Jamaladdin (XII - XIII) in the village of Pensar (Butasar) on the Lenkeran-Astara road, Gadiriyya in Shikhar village in Jabrayil region, Movlana Sheikh Yusif (XIV) in the village of Shikhar in Khachmaz region, Sheikh Mansur (XIV - XV) in the village of Harza in Qabala region, Khalvatiyya in the village of Pir Vahid and Sheikh Mazyad (XVI) in Agbil village in Quba, and Nagshibandiyya and its branch Aleviyya in the north-east of Azerbaijan. (2, 21-31, 31-51)

There were many similar Sufi dervish centres on the ancient caravan trading routes in Azerbaijan. However, a shipping lane from Europe to India via the Mediterranean Sea, opened early in the nineteenth century, was effectively a by-pass of the Silk Route and other caravan and trade routes. These ancient routes, extending from Anatolia via Azerbaijan along the Araz River to China, lost their importance and the Sufi centres dotted along them also fell into disuse.

Bibliography

1. Mashadixanim Neymat. The sacred places in Azerbaijan (social and ideological, economic and political centres). Baku, 1992.

2. Neymat M.S. The Corpus of Epigraphic Monuments of Azerbaijan V. II (Arabic-Persian-Turkic Inscriptions of Sheki-Zagatala Zone of the XIV - Early XX cc). Baku, 2001.

3. Triminghem J.S. The Sufi Orders in Islam. Translation from English under the edition and with foreword of O.F. Akimushkin. М., 1989.

4. Evliyalar Ansiklopedisi, volume II, Istanbul, 1992.

5. Ismet Zeki Eyuboglu. Bütün Yönleriyle Tasavvuf, Tarikatlar, Mezhebler tarihi. Istanbul, 1990.

6. Neymat M.S. The Corpus of Epigraphic Monuments of Azerbaijan V. III. Baku, 2001.

7. Neymat M.S. The Corpus of Epigraphic Monuments of Azerbaijan V. I, Baku, 1991.

8. Neymat M.S. The Corpus of Epigraphic Monuments of Azerbaijan V. III, Baku, 2001.

9. Huseyn, Bedai ul - vekai. Publication, introduction and general edition by A.N. Tvertinova.M., 1961.

10. Bertels Y.E. Sufism and Sufi Literature. Selected works. М., 1965.

11. Ali-zadeh А.А. Social and economic history of Azerbaijan XIII – XIV cc. Baku, 1956.

12. Asadov М.А. Azerbaijan in XIII- first half of XV c. (based on the essay of Bard ad – Dina Makhmud al – Ayuni “Ikd al – juman fi tarikh akhl az - zaman”, Authoref. Baku, 1996.

13. Guliyeva V.А. the role and position of the Muslim clergy in the social and political life of Azerbaijan in XIX – early XX cc from the perspective of Armenian-Azerbaijani relations. Baku, 2003.

14. Vassaf al – Hazrat Abdullah ibn Fazlullah. Kitabi Tajziyat al – amsar va tajziyat al – asar.Bombey, 1266.

15. Fazlullah Rashid ad – Din. Jami at – tavarih. Vol. III. Translation from Persian by A.K.Arends. The compiler of the critical scientific text in Persian – A.A.Alizadeh. Baku, 1957.

16. Stroyeva L.V. About the social nature of the Islamist movement in Iran in XI – XIII centuries.// Vestnik LSU. 1963, №20, issue 4.

17. Stroyeva L.V. Movement of Islamists in Isfakhan in 1100 – 1101s. Vestnik LSU, 1962, №4, issue 3.

18. Neymat M.S. The Corpus of Epigraphic Monuments of Azerbaijan (Arabic-Persian-Turkic Inscriptions of Guba – Khachmaz Zone and southern Dagestan of the VIII - Early XXcc).Baku, 2008.

19. Krachkovskaya V.A. Ornamented tiles of the tomb of Pir Huseyn. Tbilisi, 1946.

About the author: Mashadikhanim Neymat PhD is a corresponding member of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences. She is an expert on Azerbaijan epigraphy and the author of fundamental research works and a multivolume set on Azerbaijan epigraphy.