There are poets who are great and there are poets who are the greatest of the great. The Azerbaijani poet Mirza Alakbar Sabir certainly is the latter. His life and work traversed the 19th and 20th centuries (1862-1911). 150 years have passed since his birth, yet his poetry lives on. Many lines from his poems are now common expressions. Modern readers find that even today his poetry reflects the reality of life in Azerbaijan. In this article we take a brief look at his life, work and the enduring effect of a genius that has inspired generations of artists to interpret his writings.

There are poets who are great and there are poets who are the greatest of the great. The Azerbaijani poet Mirza Alakbar Sabir certainly is the latter. His life and work traversed the 19th and 20th centuries (1862-1911). 150 years have passed since his birth, yet his poetry lives on. Many lines from his poems are now common expressions. Modern readers find that even today his poetry reflects the reality of life in Azerbaijan. In this article we take a brief look at his life, work and the enduring effect of a genius that has inspired generations of artists to interpret his writings. He was born on 30 May 1862, in Shamakha into the family of merchant Zeynalabdin Tahirzadeh. His early education would prepare the way for his future poetic work. First he attended a Moslem ecclesiastical school and then moved on to the usuli-jadid (new-method) school of Seyid Azim Shirvani, which was considered very progressive at that time. Alakbar, as he was known, revealed his poetic talent at a very young age. Later he would prove that this was no flash in the pan. He would go on to write many poems that explore both positive and negative features of life in Azerbaijan. In the end, Mirza Alakbar Sabir’s body of work would make an important contribution to the country’s long poetic tradition.

Like all really creative personalities, Sabir was adept at analyzing the world around him and turning it into artistic expression. While the young Alakbar was studying at the ecclesiastical school he was beaten by the mullah for violating the rules. This is how he described the event:

I was fasting in Ramadan. I was very hungry. And the mullah beats me when I am writing...

Truth before wealth

With this brief passage he expressed his protest against events happening around him and showed his opposition. This and other events soon determined Sabir’s particular and just approach towards the world; he had no doubts when defining the path his life would take. He could have become a merchant and lived a life of ease and wealth. Instead he chose the difficult life of a poet, disclosing the naked truth about the troubles that people faced in his time.

In 1908 Mirza Alakbar Sabir wrote:

What are you staring at? Perhaps it is your own wry face you see?

He was the Majnun of truth in his own period, but his brand of poetry still strikes us as fresh and expressive today. In the mere 49 years that he lived, Sabir was able to cleave the ‘rock of indifference’ towards reality and to build ‘a fresh spring of thoughts’ in its place, where love overcomes sorrow. That is why even today he keeps pace with us.

In his famous Fakhriyya, one of the treasures of our poetic heritage, Sabir acquaints us with ourselves. Although he met death in mid-life, he never stopped speaking the truth. His creative life coincided with a difficult period in Azerbaijan’s history. His poetry reflects the society he saw in his time. He openly expressed his love for his nation but rejected fustiness and outmoded ways. He was a struggling poet, but every new piece of writing was eagerly awaited by his admirers. His original and truthful take on events could deal a crushing blow to evil-doers in society. His poetry certainly had a satirical spirit but it also manifests the poet’s love for his nation and belief in its future. Thus, the Hophopnameh collection of his poems, which includes his confidence that he will be understood some day, is in fact a tirade aimed at the elimination of ignorance. The essence and the meaning of his poem ‘I came for you!’ dedicated to his ideological friends and considering the future for himself and the nation, already appears a fully-formed part of our history.

Hophopnameh – a giant mirror…

It would be no exaggeration to say that he established himself as a great artist with his famous Hophopnameh, which took six years to complete. His poetry lifts our spirits and eases the problems that weigh us down. Perhaps this is why it is not so difficult for the reader to imagine everything described therein. Sabir was able to take even the smallest incidents of ordinary life and transform them beyond the mere factual. Describing events in satirical mood, he would skilfully turn the humdrum into art. If we may quote the literary critic N. Pashayev,

Sabir turned poetry into an ideological weapon in the political and social thinking of the people. The new poetic contexts created by Sabir became a shining light for those suffering exploitation and oppression, and for despots it was a merciless fire. He spoke out against shabbiness and reaction. This poetry became a giant mirror reflecting clearly and justly both the positive and negative aspects of society. It showed the Eastern nations ways to struggle against tyranny, oppression and set traditions.

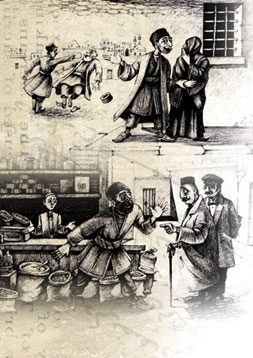

This satire was polished over time and was very soon enriched with new and innovative features; finally becoming an artistic and aesthetic spring within a deep philosophical context. We think that upon reading this poetry it was not difficult for Azim Azimzade and the other artists to provide artistic images for it. The poems, on a variety of topics, were written in a pure folk language and appeared to be very simple stylistically, yet they were, at the same time, very poetic. They were stimulating, picturesque and had extraordinary and meaningful contexts.

…provoking images

There are very striking and lasting images in the lines of Hophopnameh. As an artist, the poet was able to create social types and images of different characters in a very compact form but meaningful enough to be felt. We meet the exploiters of workers and villagers, superstitious religious people and Mashhadis (religious pilgrims – ed), women who suffered difficult fates, cosmopolitan intellectuals, grocers, misers, ruffians, tyrants and despots, people spreading prejudice, and many more. Sabir put every type in the context of their origins, their language and their characteristic psychology. With this panoply to choose from, he created unlimited opportunities for artists to portray the characters. His language was a literary means of opening up the world of visual art. Azim Azimzade and Ismayil Akhundov, Najafgulu Ismayilov, Arif Huseynov, Elchin Mammadov, Bayram Hajizadeh, and others who later illustrated Hophopmaneh were the beneficiaries. The uniqueness of every image that these artists created or revived at various periods and the new shades they directed towards the revelation of character and mood, were derived totally from the tragicomic spirit of Hophopnameh.

There is no doubt that Sabir’s poems are remembered for the power of the imagination and the brushes of these visual artists, as well as for their dramaturgical qualities. The extraordinary harmony of his colourful rhymes also helped. Thus, there is great dramatic material in the conversations and events on the pages of Hophopnameh. Behind every poem we see Sabir’s talent to create a story, an image, or a type. He separated people into negative and positive. He created a dynamic development of ideas and took the events of real-life that he observed into the artistic arena to create a carnival of conflict, development, climax, decline and conclusion in every poem. Thus we can claim that the poet was also a great dramatist.

In fact, it is the poetic exaggeration that artists focus on when imaging his work. The poet applied the principles of carnival in his works and made his characters speak, sometimes criticizing his own kind to achieve the grotesque, the exaggeration, sarcasm and irony expressed in the drawings; he presented a plot reminiscent of a theatrical scene. The artists sensed it in the details and by selecting a different angle, achieved harmony between performance and aesthetic within their own works.

The pen outlives the poet….

Although Sabir’s poems appeared regularly in the magazine Molla Nasreddin from 1906, visual artists only approached them after the poet’s death. He never saw a book of his own works and the first small – 104 pages – edition was published in 1912 with donations collected by his close friend Abbas Sahhat and his teacher Mahmud bey Mahmudbeyov. The publishers linked the book to Sabir’s famous pen name Hophop (a colloquial name for the hoopoe bird) and called it Hophopnameh. It was not illustrated. A second, better, edition was published in 1914. Published by the joint efforts of Abbas Sahhat, Mahmud bey Mahmudbeyov, Mehdi bey Hajinski and Seyid Huseyn included twenty-four colour illustrations by the 34-year-old Azim Azimzade, who later gained the sobriquet, the Sabir of art.

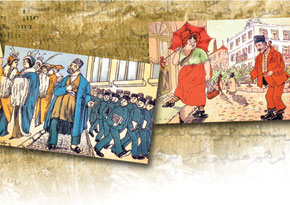

The first edition of the book during the Soviet era (1922) was embellished by 34 other Azimzade illustrations. Such was the particularity of the vision that the artist applied to Hophopnameh that, although various others after him tried to provide an artistic design to this peerless poetry, his approach is regarded as a major contribution to Azerbaijani book illustration because of its highly successful and attractive harmony of content and illustration. Firstly, Azimzade was very closely acquainted with the life and the history, the ethnography, traditions, material and cultural patterns of Azerbaijan and these were the root of his response to Sabir’s poems. The artistic and aesthetic value of this work surely endures. Azim Azimzade, who had no professional education during his 63 years, realized the mission that he carried in his soul and thus became an artistic phenomenon. Aside from his great talent, his success was also due to Molla Nasreddin, which made ‘I came for you!’ its slogan at the time he began working there.

From our modern vantage point, we can say that this magazine played a vital role in the creative development of both Sabir and Azimzade. With the great Jalil Mammadguluzadeh at its head, Molla Nasreddin really was a great school of its time.

The illustrations that Azimzade drew for various poems were notably sharp in their satire and ridicule of the character types. The illustrations that he drew for Oh, Inhabitants of Shirvan; I Don’t Care About the People!; Khanbaji, My Heart is Pained with Sorrow; The Ploughman; I Will Not Let Him Study, Leave Me Alone!; Don’t Let Him Come! and other poems were more than adequate responses to Sabir’s tragicomic poetry, both ridiculous and thought-provoking.

… for generations of artists

In 1934, while Azim Azimzade still lived, the artist Ismayil Akhundov was entrusted with the design of a new edition of Hophopnameh. Although quite young, he rejected Azimzade’s way and offered a new approach to Sabir’s legacy. While previous designers had divided the poet’s works into different topics, Akhundov’s illustrations united them by general characterisation.

In 1962, illustrations of Hophopnameh prepared by Najafgulu Ismayilov and published in celebration of the poet’s centenary, continued the Azimzade tradition in providing a commentary on the literary work, but he also showed individuality of approach. His illustrations of Patience; Ardebil; My Sixty Years of Life was Ruined in You!; Mamdali’s Philandering in Europe; I am Afraid; Complain; To the Baku Wrestlers and other poems are particularly interesting.

A new edition of Hophopnameh published in 1980 caused a great ballyhoo and outcry in local literary circles. The reason was the very different design given to the book by the young artist Arif Huseynov. The final lesson from the disputes that arose was that a different reading of Sabir is possible and should be welcomed rather than condemned.

The black and white pictures created by Huseynov, who embraced not only the story and the idea behind the poems, but also the poet’s creative style, caused anxiety because they revealed Sabir’s philosophical meaning. In those works, the dissonance between the composition and the characters criticized by the wordsmith in various psychological states underlines the point that this could be happening anywhere. The art points at a large number of false national heroes and cruel, heartless people. Finally, it is consonant with the thoughts of the poet and complements them.

How long will Sabir remain modern?

Arif Huseynov’s design for the edition of Hophopnameh published and dedicated to Sabir’s 150th anniversary contains forty new pictures. This, of course, adds greatly to its significance and represents a synthesis of the artist’s particular vision. Huseynov read the philosophical meaning detailed in each of Sabir’s paintings and provided artistic images in tune with the writer’s style. He has created a fount to plunge one into a vortex of thought. The artist feels that the troubles which have pursued our people for centuries and the problems which often seem insoluble are apparent in the writings. He believes that, artistically, Sabir is still modern and relevant today. His images show people exploited and working in the fields; they do not want education but envy the Europeans who fly balloons, having mastered the principles of science. He shows us the poet’s sorrow at his people’s ignorance and intellectual darkness. He shows us cosmopolitan intellectuals who dream about foreign women. The painter’s works invite the viewer into a dialogue, but are also questioning. One question that he asks himself is: How long will Sabir remain modern?

We should mention that talented artist and actor Elchin Mammadov had a different vision of Hophopnameh twelve years after Huseynov’s courageous statement in 1980. His pictures aimed to provoke laughter at Sabir’s characters and not to offer advice or admonition. He portrayed the characters at the junction of cartoon and caricature.

Prominent cartoonist Bayram Hajizadeh also adopted an individual approach to Hophopnameh. Combining his sense and vision as a cartoonist with the reality of the stories, he provided a convincingly ironic and critical commentary. His artistic responses to Don’t Let Him Come; The Century is Calling Us, We Don’t Respond; I am Afraid; A Liking for Money and other poems, conform to the tragicomedy that is the expression of the poet’s critique of our social wounds and troubles; they are both impressive and memorable.

Endless inspiration

Hophopnameh, the comprehensive outcome of Sabir’s meaningful life, has been a source of inspiration for artists and sculptors ever since his death. We might mention the painted, graphic and sculptural works of such masters as Sattar Bahlulzadeh, Mikayil Abdullayev, Alakbar Rzaguliyev, Ogtay Sadigzadeh, Sadig Sharifzadeh, Asaf Jafarov and Tahir Salahov; sculptors Jalal Garyagdi, Omar Eldarov, Khanlar Ahmadov, Sahib Guliyev, Gorush Babayev, Fuad Salayev and Akif Asgarov, as well as Nusrat Hajiyev, Ulviyya Hamzayeva, Adil Rustamov, Orkhan Huseynov, Amrullah Israfilov, Yashar Samadov, Elturan Avalov, Gunduz Agayev and Hasanaga Mammadov.

There are also many poems for children among the poet’s works written from 1906 to 1911. It would be true to say that many generations of Azerbaijanis have grown up with these poems. The illustrations drawn by several generations of artists to his books The Child and the Ice; The Spring Days; A Present for School Children and Fables were very much loved by readers and are as attractive as the poems. The illustrations by artists Kazim Kazimzade, Ali Verdiyev, Ismayil Mammadov, Nazim Babayev, Rasim Babayev, and Rafig Mehdiyev must be mentioned in this context.

After the Bolshevik occupation of Azerbaijan in 1920, the question of creating a monument to the first local writer in Baku arose. It was not surprising that the Soviet ideologists chose Sabir. It was a response to the great fame that the poet had gained among the population in the early 20th century. Iakov Keylekhis’ concrete monument was erected in 1922 and remained in what is now Sabir Park until 1958. At that time the monument was replaced by the bronze statue created by Jalal Garyagdi; the old one was moved to Balakhani settlement where the poet worked as a teacher for a certain period.

The poetry of Sabir embraces wisdom and lyrics. It is directed towards the expression of reality, first of all as an impartial ‘literary mirror’. The sharp character of the truth he constantly expressed was the result of this conscious decision.

In his declining years, he was invited to Tiflis from Shamakha for medical treatment at the expense of Jalil Mammadguluzade and his wife Hamida khanim. If he had agreed to have the surgery, perhaps he would have recovered. But he said, in his usual style,

My stomach is not a purse that you can open and close. What if you cut me and it doesn’t help?

Thus he refused to have the surgery. He was a true poet of the people. He said,

I sacrificed my insides in service of the people. If life let me, I would sacrifice my bones too.

He died too early, but continues to inspire. We prove the immense importance of his work by quoting him at every turn. His immortality as a poet is undeniable.

Editor’s note: Visions of Azerbaijan will continue its celebration of 150 years of Sabir with an article on his language and philosophy in a future edition.