It was on a gloomy, rainy evening back in 1995, at my cosy local cinema, the Renoir, not far from London’s Russell Square, when it first dawned upon me. Watching films from unexpected and unusual places was my way to quench that everlasting hunger for getting to know the world and travelling in time and space. On that particular evening I was mesmerized by Milčo Mančevski’s ‘Before the Rain’. It was the story of a London-based war photographer, Alexander Kirkov, who decides to go back to his native Macedonia, that got me wondering about what it would feel like to return years later and discover my own homeland over again.

As it turned out, I was destined to go back to Azerbaijan – the place from where I had set off to explore the world - rather soon, and not years later, as I imagined that evening watching the Macedonian film. When you are a professional reporter, imagining and planning things far ahead is a silly business. My work as a journalist took me back to Azerbaijan on many an occasion. I happened to be in Baku on a tragic day when, to my anguish and disbelief, I had to report the terrorist bombing in the city’s underground that claimed the lives of dozens of innocent people, including that of one of my all-time favourite musicians. I travelled along the shores of the Caspian trying to investigate the mysterious cycle of the sea’s rising levels. I watched the construction of a major pipeline that stretched for thousands of miles from the Caspian shore all the way to the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean. I thought I had left no stone unturned discovering, as it were, my own country.

In the autumn of 2012, I was privileged to make another comeback, although this time not as a journalist, but in the more unusual role of guide. I spent two weeks travelling across the country, helping first French and then British travel journalists and photographers to discover for themselves what Azerbaijan has to offer. The journey took us to various corners of this ‘small, yet such a diverse place’, as one of the visitors called the country. From cobbled, curvy streets in the Old Town of Baku, to the medieval mausoleums and shrines of Nakhchivan, to six-domed synagogues in Quba’s Red Settlement, to the breathtaking slopes of the Caucasus surrounding Qabala, to cosy tea-houses and caravanserais in Sheki and an ancient Christian church in the village of Nij.

In search of the Prophet’s Ship

Most foreign visitors to Azerbaijan dedicate their time and whatever adventurous inclinations they may possess to discovering the mainland, hardly ever venturing as far as Nakhchivan. But those few real adventurers who made it to what is often described by the unattractive geopolitical term exclave experienced a feast of medieval history, untouched natural beauty and exquisite tastes of local dishes and fresh produce, such as citrus and walnuts, to name just two. Many tourists are baffled not so much by Nakhchivan’s unusual geographical detachment from the rest of the country, but rather by the numerous unfounded and wrong Internet entries about the history of this region. It was a myth that drew us to this mysterious and undiscovered corner of Azerbaijan. Mind you, archaeologists, historians and true followers of the Old Testament may dismiss the very term myth. The clue, as often, is in the name – many believe that the word Nakhchivan derived from the name of the Biblical prophet, Noah (Nuh - in Azerbaijani).

I wouldn’t even begin to argue the historical merits of the local belief, but Nakhchivanis say that it is here, on the crest of Ilan Dagh that Noah’s Ark hit land and found refuge. I had seen the image of this broke-back mountain with its unusual two-pronged summit so many times before. Indeed, Ilan Dagh (Snake Mountain) is probably Nakhchivan’s most recognisable landmark. Yet seeing it with your own eyes mystifies and dazzles you so much that you readily believe any of the legends or tales that the locals have in abundance. In fact the sight of Ilan Dagh at sunset mesmerises and enchants you so completely that your imagination begins to depict the contours of the legendary Ark. Of course, it must have been the prow of the ship that hit the summit and split it in two… what else could it have been? – you even embark on an internal dialogue with the critical thinker (side-effects of long-running journalistic career) inside you.

For years I have dreamed of hiking in Mongolia and mountaineering in the ‘lowlands’ of Nepal. Now I know that I need not seek elsewhere – Nakhchivan is a hiker’s paradise. The barren wild landscapes, the striking, edgy mountains that appear like mirages out of nowhere in the midst of plain, fascinating sandstone hills like giant lion paws, natural salty caves and medieval fortresses, would overwhelm the most experienced tracker. And this region has all the ingredients to help adventurers to recover those burnt calories. Without delving too far into the world of the gastronomic wonders of Nakhchivan, I will say only this: having dined on five continents and in scores of different countries, the local fresh-water carp is one of the most delicious meals I’ve ever tried. And I wouldn’t be surprised if it was the taste of the local fish that made Noah decide to moor his Ark right at the top of Ilan Dagh.

Honest skewer-boy

Western travellers like to share their wisdom and experiences, especially when it comes to lamenting the locals – be it in Africa, Central America or especially the Middle East - for their often fraudulent antics or hassling in the bazaars or souks. Alas, sometimes these small-time crooks, greedy bartenders or intrusive street-vendors ultimately spoil an otherwise inspiring adventure. In a world where the sole purpose of interaction between locals and visitors is, sadly, to get the tourists’ cash, the hardest currency for me is honesty.

It was after visiting the Jewish community in Red Settlement, Quba, that we ventured into the forest to breathe properly crisp mountain air and have one of those meaningful conversations that can only happen when you get down to glass after glass of velvety, balmy Azerbaijani tea surrounded by stately old plane-trees and lulled by the soothing ramble of the waters of the Gudyalchay down in the gorge. Fresh air and forest chill surely soon remind you that over the centuries Azerbaijanis have mastered the art of cooking minced lamb to unrivalled perfection. Needless to say, proper meaningful conversations require an intake of pure protein and, in this part of the world, a true Caucasian toast.

It turned out, though, that we faced a challenge of a theological nature that threatened gastronomic constraint. One of my fellow-travellers, a female French journalist of Jewish origin who did not treat lightly the strict rules of Judaism, could not touch the much-praised lule-kebab that was not cooked in accordance with kosher tradition. This meant that she could not try any meat from skewers that had been used before, for example to grill vegetables. I told the young local man who was looking after us on that day of our respectful duty to feed our guest the best lule-kebab in the whole of Quba, but without infuriating the Almighty. Brainstorming is like a national sport to the English, but this time it was the Qubans who came to the rescue of the Continent. Our waiter suggested that he would rush down to the nearby village to buy some new skewers. Surely, we thought, Azerbaijani skewers on their maiden grilling voyage would be compatible with kosher tradition. On hearing the news of the virgin skewers, Sonia, the cause of this quick-witted invention, gave us that most enchanting smile that only French women can offer. It pleased me in a bizarre sort of way that the reason for that particular manifestation of natural beauty and Gallic charm was an Azerbaijani kebab.

Events, however, brought not another smile, but what I thought were clear glimpses of tears in the Frenchwoman’s eyes. Having spent an hour or so running to nearby restaurants and local villagers’ homes, our waiter came back to announce something that impressed us all in the midst of our discussion on the virtues of local sage and oregano. He told us that he had found some skewers he thought were new, but he could not be sure or vouch for their chastity, which meant that we faced another problem in proving to a nation of gourmets that our way of cooking lamb is unsurpassed even by master-chefs from the court of Louis XIV. My compatriot came to my aid again, saying that he would make the man behind the grill use wooden sticks as skewers.

As for the tears I thought I saw, I believe they were drawn by the boy’s integrity. The lesson of this episode was that honesty was still an important notion in this country, as Eugene Costello, British traveller and journalist, termed it. The boy could easily have claimed that the skewers he had found were indeed new and met the client’s requirement. I will never know whether it was the admiration that the Quban boy felt for the foreign lady’s respect for her creed, or if it was the recognition of a good deed that the boys in those mountainous villages learn from their mothers’ lullabies. It felt like he had just made the choice that would be natural to him throughout his life. I learnt another lesson about indispensable integrity from an adolescent boy in the north of Azerbaijan… and I loved every bit of it.

‘The three things’ quiz

In those two weeks of discovering Azerbaijan through the eyes of western journalists we had many a conversation about what had impressed my guests the most.

Describing every comment would be too lengthy a process, so to reflect the gist of what my fellow travellers discovered, I asked a few of them about the three most striking features of Azerbaijan. Eric Pasquier is a French traveller and a journalist with years of experience writing stories and taking pictures from almost every corner of the globe. He honestly said that limiting his impressions to just three things would be difficult:

All I knew before coming here is that Azerbaijan is located at the crossroads between Europe and Asia, which, alas, is a journalistic cliché. I also knew that it was part of the former Soviet Union. What I saw was quite astonishing. I found it bizarre that the general public in the West are oblivious to Azerbaijan’s remarkable secularism and modernity. I was impressed by people’s kindness and desire to show how hospitable they are. And as a Frenchman, I was pleasantly surprised and even happy to meet so many Francophiles in Azerbaijan. I have travelled the world and I have to say that Baku surprised us all as a very modern and clean city with some impressive traditional and modern architecture. It’s this synergy of ultra-modern buildings that coexist with the charming balconies of the medieval Old Town that is most striking. Flashy modern cars sharing the roads with Russian Ladas is also an interesting sight. But it’s the mingling of people, not cars, that impressed us the most. It is quite remarkable that Muslims here interact with Christians and Jews without any problems, without any animosity. I have one piece of advice for anyone who comes here - embrace without reservation the smiles that will be offered to you on daily basis.

A Londoner and avid adventurer, Eugene Costello came to Azerbaijan after spending three weeks motorcycling in the Himalayas. But did this trip take him to expected heights?

I was really impressed with the genuine friendliness and hospitality of the people. It seems they are not spoilt by this impatience towards foreign visitors you see elsewhere. I was also impressed by a variety of landscapes in Azerbaijan, ranging from the almost Dubaiesque modern cityscapes of Baku to endless untouched plains reminiscent of the Mongolian steppes, to the majestic beauty of the mountain slopes up in the Caucasus. It’s amazing that one small country can embrace such a variety of places. And finally it struck me that so many things in Azerbaijan almost screamed ‘history’.

Sharon Livingston is writing about the most interesting cities in the world and unusual places to visit for the ‘Jewish Chronicle’, the largest paper serving Britain’s Jewish community. This is what surprised her:

I was impressed by the country’s diversity - as you travel around Azerbaijan, you realise there are various ethnic groups there. Seeing a thriving Jewish community was also a pleasant surprise. Before I went to Azerbaijan I had no expectations, but I thought I was going to an Asian country. So I was struck by the European aspiration of the people and the European feel to Baku’s architecture. And I also discovered the wonderful Azerbaijani cuisine with such a variety of fresh herbs and divine yoghurt. I’m sure it will one day become popular, even with the spoilt Europeans.

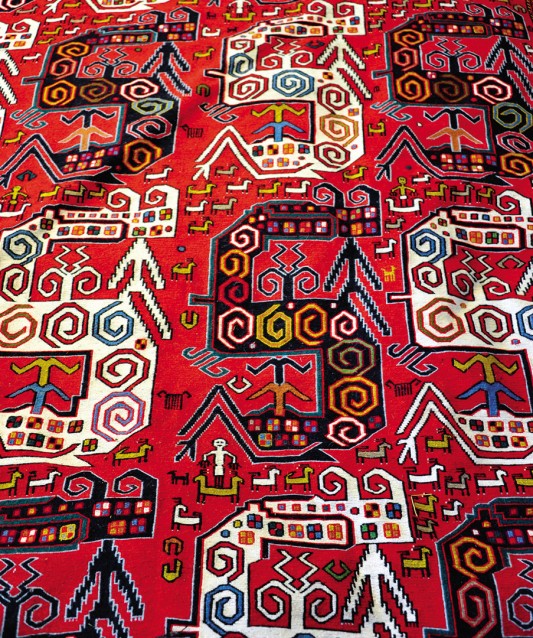

As for me, discovering my own country through the eyes and camera lenses of those visiting it for the first time turned out to be a very rewarding and inspiring adventure. Not only because I saw experienced and hard-to-surprise travellers admire the landscapes of my land or enjoy the delights of the local cuisine. Not only because I realised that these probing journalists were genuinely impressed by the warmth and hospitality of the Azerbaijanis they had met. No, the most inspiring part of travelling as a guide was that I had a chance to see all-too-familiar things from new angles and perspectives. What a great feeling it is, for example, to be amazed again by the colours and patterns on the walls of the Khan’s palace in Sheki. Or to see afresh the little things and notions that we often take for granted, like a properly brewed cup (or in the Azerbaijani setting, a glass) of tea.

And, as Marco Polo famously put it centuries ago, I haven’t told half of what I saw…

About the writer: Emil Agazade is a London-based traveller and journalist who works for The European Azerbaijan Society

As it turned out, I was destined to go back to Azerbaijan – the place from where I had set off to explore the world - rather soon, and not years later, as I imagined that evening watching the Macedonian film. When you are a professional reporter, imagining and planning things far ahead is a silly business. My work as a journalist took me back to Azerbaijan on many an occasion. I happened to be in Baku on a tragic day when, to my anguish and disbelief, I had to report the terrorist bombing in the city’s underground that claimed the lives of dozens of innocent people, including that of one of my all-time favourite musicians. I travelled along the shores of the Caspian trying to investigate the mysterious cycle of the sea’s rising levels. I watched the construction of a major pipeline that stretched for thousands of miles from the Caspian shore all the way to the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean. I thought I had left no stone unturned discovering, as it were, my own country.

In the autumn of 2012, I was privileged to make another comeback, although this time not as a journalist, but in the more unusual role of guide. I spent two weeks travelling across the country, helping first French and then British travel journalists and photographers to discover for themselves what Azerbaijan has to offer. The journey took us to various corners of this ‘small, yet such a diverse place’, as one of the visitors called the country. From cobbled, curvy streets in the Old Town of Baku, to the medieval mausoleums and shrines of Nakhchivan, to six-domed synagogues in Quba’s Red Settlement, to the breathtaking slopes of the Caucasus surrounding Qabala, to cosy tea-houses and caravanserais in Sheki and an ancient Christian church in the village of Nij.

In search of the Prophet’s Ship

Most foreign visitors to Azerbaijan dedicate their time and whatever adventurous inclinations they may possess to discovering the mainland, hardly ever venturing as far as Nakhchivan. But those few real adventurers who made it to what is often described by the unattractive geopolitical term exclave experienced a feast of medieval history, untouched natural beauty and exquisite tastes of local dishes and fresh produce, such as citrus and walnuts, to name just two. Many tourists are baffled not so much by Nakhchivan’s unusual geographical detachment from the rest of the country, but rather by the numerous unfounded and wrong Internet entries about the history of this region. It was a myth that drew us to this mysterious and undiscovered corner of Azerbaijan. Mind you, archaeologists, historians and true followers of the Old Testament may dismiss the very term myth. The clue, as often, is in the name – many believe that the word Nakhchivan derived from the name of the Biblical prophet, Noah (Nuh - in Azerbaijani).

I wouldn’t even begin to argue the historical merits of the local belief, but Nakhchivanis say that it is here, on the crest of Ilan Dagh that Noah’s Ark hit land and found refuge. I had seen the image of this broke-back mountain with its unusual two-pronged summit so many times before. Indeed, Ilan Dagh (Snake Mountain) is probably Nakhchivan’s most recognisable landmark. Yet seeing it with your own eyes mystifies and dazzles you so much that you readily believe any of the legends or tales that the locals have in abundance. In fact the sight of Ilan Dagh at sunset mesmerises and enchants you so completely that your imagination begins to depict the contours of the legendary Ark. Of course, it must have been the prow of the ship that hit the summit and split it in two… what else could it have been? – you even embark on an internal dialogue with the critical thinker (side-effects of long-running journalistic career) inside you.

For years I have dreamed of hiking in Mongolia and mountaineering in the ‘lowlands’ of Nepal. Now I know that I need not seek elsewhere – Nakhchivan is a hiker’s paradise. The barren wild landscapes, the striking, edgy mountains that appear like mirages out of nowhere in the midst of plain, fascinating sandstone hills like giant lion paws, natural salty caves and medieval fortresses, would overwhelm the most experienced tracker. And this region has all the ingredients to help adventurers to recover those burnt calories. Without delving too far into the world of the gastronomic wonders of Nakhchivan, I will say only this: having dined on five continents and in scores of different countries, the local fresh-water carp is one of the most delicious meals I’ve ever tried. And I wouldn’t be surprised if it was the taste of the local fish that made Noah decide to moor his Ark right at the top of Ilan Dagh.

Honest skewer-boy

Western travellers like to share their wisdom and experiences, especially when it comes to lamenting the locals – be it in Africa, Central America or especially the Middle East - for their often fraudulent antics or hassling in the bazaars or souks. Alas, sometimes these small-time crooks, greedy bartenders or intrusive street-vendors ultimately spoil an otherwise inspiring adventure. In a world where the sole purpose of interaction between locals and visitors is, sadly, to get the tourists’ cash, the hardest currency for me is honesty.

It was after visiting the Jewish community in Red Settlement, Quba, that we ventured into the forest to breathe properly crisp mountain air and have one of those meaningful conversations that can only happen when you get down to glass after glass of velvety, balmy Azerbaijani tea surrounded by stately old plane-trees and lulled by the soothing ramble of the waters of the Gudyalchay down in the gorge. Fresh air and forest chill surely soon remind you that over the centuries Azerbaijanis have mastered the art of cooking minced lamb to unrivalled perfection. Needless to say, proper meaningful conversations require an intake of pure protein and, in this part of the world, a true Caucasian toast.

It turned out, though, that we faced a challenge of a theological nature that threatened gastronomic constraint. One of my fellow-travellers, a female French journalist of Jewish origin who did not treat lightly the strict rules of Judaism, could not touch the much-praised lule-kebab that was not cooked in accordance with kosher tradition. This meant that she could not try any meat from skewers that had been used before, for example to grill vegetables. I told the young local man who was looking after us on that day of our respectful duty to feed our guest the best lule-kebab in the whole of Quba, but without infuriating the Almighty. Brainstorming is like a national sport to the English, but this time it was the Qubans who came to the rescue of the Continent. Our waiter suggested that he would rush down to the nearby village to buy some new skewers. Surely, we thought, Azerbaijani skewers on their maiden grilling voyage would be compatible with kosher tradition. On hearing the news of the virgin skewers, Sonia, the cause of this quick-witted invention, gave us that most enchanting smile that only French women can offer. It pleased me in a bizarre sort of way that the reason for that particular manifestation of natural beauty and Gallic charm was an Azerbaijani kebab.

Events, however, brought not another smile, but what I thought were clear glimpses of tears in the Frenchwoman’s eyes. Having spent an hour or so running to nearby restaurants and local villagers’ homes, our waiter came back to announce something that impressed us all in the midst of our discussion on the virtues of local sage and oregano. He told us that he had found some skewers he thought were new, but he could not be sure or vouch for their chastity, which meant that we faced another problem in proving to a nation of gourmets that our way of cooking lamb is unsurpassed even by master-chefs from the court of Louis XIV. My compatriot came to my aid again, saying that he would make the man behind the grill use wooden sticks as skewers.

As for the tears I thought I saw, I believe they were drawn by the boy’s integrity. The lesson of this episode was that honesty was still an important notion in this country, as Eugene Costello, British traveller and journalist, termed it. The boy could easily have claimed that the skewers he had found were indeed new and met the client’s requirement. I will never know whether it was the admiration that the Quban boy felt for the foreign lady’s respect for her creed, or if it was the recognition of a good deed that the boys in those mountainous villages learn from their mothers’ lullabies. It felt like he had just made the choice that would be natural to him throughout his life. I learnt another lesson about indispensable integrity from an adolescent boy in the north of Azerbaijan… and I loved every bit of it.

‘The three things’ quiz

In those two weeks of discovering Azerbaijan through the eyes of western journalists we had many a conversation about what had impressed my guests the most.

Describing every comment would be too lengthy a process, so to reflect the gist of what my fellow travellers discovered, I asked a few of them about the three most striking features of Azerbaijan. Eric Pasquier is a French traveller and a journalist with years of experience writing stories and taking pictures from almost every corner of the globe. He honestly said that limiting his impressions to just three things would be difficult:

All I knew before coming here is that Azerbaijan is located at the crossroads between Europe and Asia, which, alas, is a journalistic cliché. I also knew that it was part of the former Soviet Union. What I saw was quite astonishing. I found it bizarre that the general public in the West are oblivious to Azerbaijan’s remarkable secularism and modernity. I was impressed by people’s kindness and desire to show how hospitable they are. And as a Frenchman, I was pleasantly surprised and even happy to meet so many Francophiles in Azerbaijan. I have travelled the world and I have to say that Baku surprised us all as a very modern and clean city with some impressive traditional and modern architecture. It’s this synergy of ultra-modern buildings that coexist with the charming balconies of the medieval Old Town that is most striking. Flashy modern cars sharing the roads with Russian Ladas is also an interesting sight. But it’s the mingling of people, not cars, that impressed us the most. It is quite remarkable that Muslims here interact with Christians and Jews without any problems, without any animosity. I have one piece of advice for anyone who comes here - embrace without reservation the smiles that will be offered to you on daily basis.

A Londoner and avid adventurer, Eugene Costello came to Azerbaijan after spending three weeks motorcycling in the Himalayas. But did this trip take him to expected heights?

I was really impressed with the genuine friendliness and hospitality of the people. It seems they are not spoilt by this impatience towards foreign visitors you see elsewhere. I was also impressed by a variety of landscapes in Azerbaijan, ranging from the almost Dubaiesque modern cityscapes of Baku to endless untouched plains reminiscent of the Mongolian steppes, to the majestic beauty of the mountain slopes up in the Caucasus. It’s amazing that one small country can embrace such a variety of places. And finally it struck me that so many things in Azerbaijan almost screamed ‘history’.

Sharon Livingston is writing about the most interesting cities in the world and unusual places to visit for the ‘Jewish Chronicle’, the largest paper serving Britain’s Jewish community. This is what surprised her:

I was impressed by the country’s diversity - as you travel around Azerbaijan, you realise there are various ethnic groups there. Seeing a thriving Jewish community was also a pleasant surprise. Before I went to Azerbaijan I had no expectations, but I thought I was going to an Asian country. So I was struck by the European aspiration of the people and the European feel to Baku’s architecture. And I also discovered the wonderful Azerbaijani cuisine with such a variety of fresh herbs and divine yoghurt. I’m sure it will one day become popular, even with the spoilt Europeans.

As for me, discovering my own country through the eyes and camera lenses of those visiting it for the first time turned out to be a very rewarding and inspiring adventure. Not only because I saw experienced and hard-to-surprise travellers admire the landscapes of my land or enjoy the delights of the local cuisine. Not only because I realised that these probing journalists were genuinely impressed by the warmth and hospitality of the Azerbaijanis they had met. No, the most inspiring part of travelling as a guide was that I had a chance to see all-too-familiar things from new angles and perspectives. What a great feeling it is, for example, to be amazed again by the colours and patterns on the walls of the Khan’s palace in Sheki. Or to see afresh the little things and notions that we often take for granted, like a properly brewed cup (or in the Azerbaijani setting, a glass) of tea.

And, as Marco Polo famously put it centuries ago, I haven’t told half of what I saw…

About the writer: Emil Agazade is a London-based traveller and journalist who works for The European Azerbaijan Society